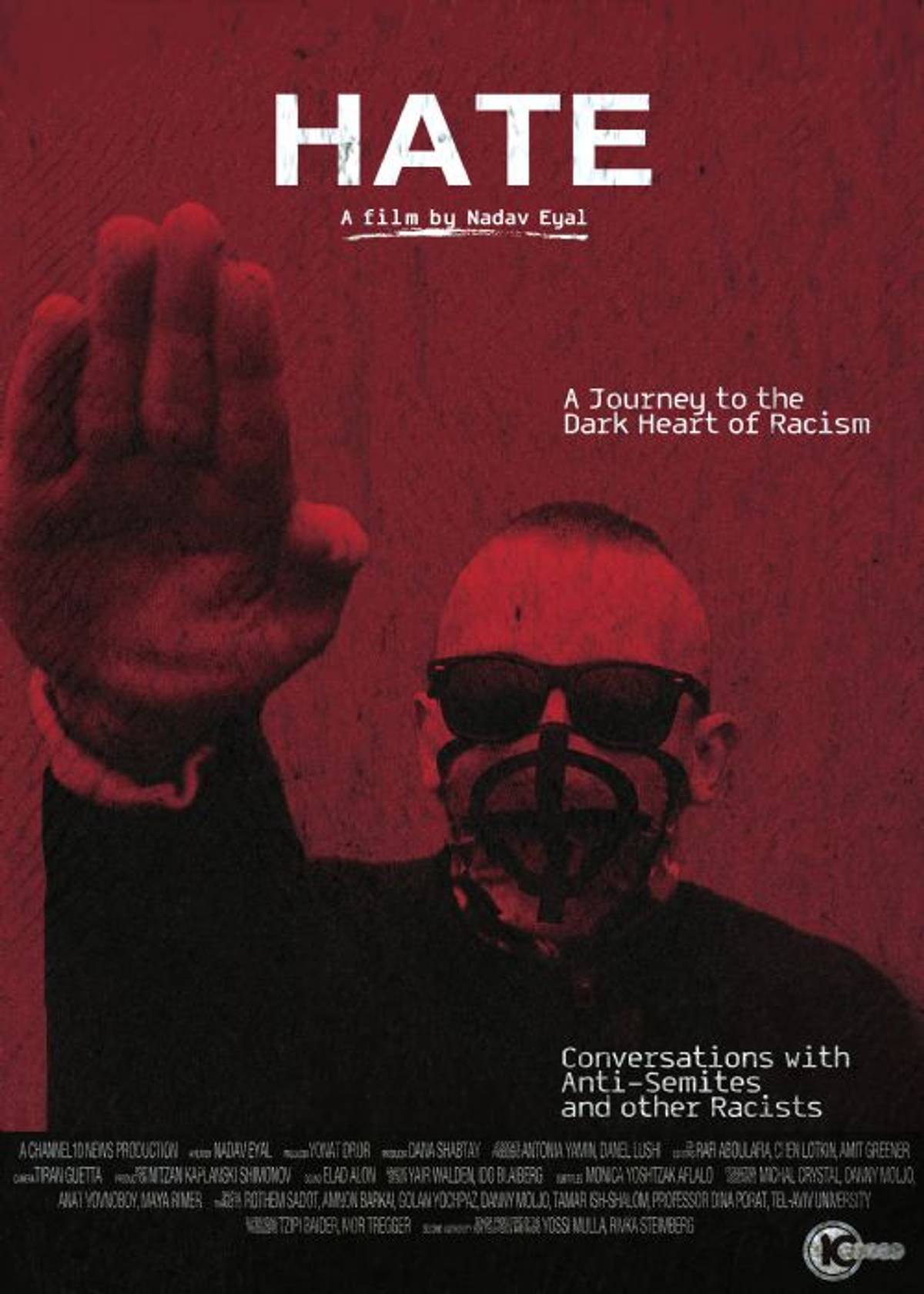

Exploring ‘Hate’

A documentary by Israeli journalist Nadav Eyal examines ‘the virus of anti-Semitism’ in Europe

Hate, a documentary by Nadav Eyal, an Israeli journalist, explores prejudice toward minorities and foreigners in Europe by uniquely engaging with both victims and perpetrators of xenophobia in an effort to “understand how the virus of anti-Semitism survives and continues to infect.” The film, which was released last year and has since received numerous awards, is set to screen in the U.S., beginning Tuesday at the JCC in York, PA, then in New Jersey and Oregon, before heading to the Hong Kong Jewish Film Festival on November 17. Eyal—influenced by his work as an international correspondent for Israel’s Channel 10, as well as by Newsweek‘s 2014 coverage of the “Exodus” of France’s Jews—made Hate because he is “interested in how [hateful] ideas become globalized.”

In the film, Eyal travels to Greece, Germany, and the UK, where he interviews Jews and Muslims, about their experiences with racism. However, it’s Eyal’s unique access to and portrayal of the perpetrators of anti-Semitism and xenophobia that sets the film apart. In Athens, where anti-Semitism looms large, Eyal meets with Konstantinos Plevris, mentor to former Greek Health Minister Adonis Georgiadis, who also appears in the film in a desperate attempt to prove he’s not an anti-Semite. Plevris, whose dissonant prose is mediated by Eyal’s scripted commentary, is a controversial far-right author and Greek Supreme Court lawyer, convicted for inciting racial hatred against Jews. As evidenced by the film’s trailer, Plevris showcases a head-scratching dogma, one in which he denies Jesus’ Jewishness, insists that there is not “one bank that is not controlled by the Jew,” indicts Jews as the cause of capitalism and communism, while praising Israel as the model state, all in one breath.

During the course of the film, Eyal accompanies eerily friendly “nipster” (“Nazi hipster”) Patrick Schroeder, the host of Germany’s neo-Nazi online show on FSN.tv who Rolling Stone once described as “a well-known, if highly controversial, figure in the German extreme right, largely because he has been open about his desire to give the German neo-Nazi movement a friendlier, hipper face.”Following a puzzling confrontation with police, Eyal meets this “nice neo-Nazi” at a campaign rally in the middle of the woods just outside the central German town of Hildburghausen (public Nazi activity is technically illegal in Germany), where they debate the merits of the Third Reich in a poignant exchange, which nearly gets lost in translation. One thing remains clear, though. In Schroeder’s confused attempt to frame himself exclusively as a nationalist, enraged that schools in Germany were forbidding the consumption of pork (presumably at the hand of Muslim immigrants), he uses words, described by Eyal, “that any sort of sound, mainstream German would not use, which are Nazi codes.” This coded language, Eyal says, has become irrevocably “contaminated” since the Holocaust.

Eyal said that most violent anti-Semitic attacks in Europe “stem out of Muslim-Jewish confrontation,” though his film focuses heavily on classical, white European radical right-wing racism in an attempt to broaden the narrative to a larger consideration of hate culture. But it seems the film doesn’t give enough explicit credit to Europe’s extreme left-wing, which has contributed its fair share of anti-Semitic rhetoric. The left-wing is more complex, Eyal said, because of the disproportionate representation of Jews within it. However, Eyal notes that the radical left-wing fails to “distinguish between legitimate criticism of Israel and racist anti-Semitism” when it combines progressive notions of anti-colonialism with graphic anti-Semitism. But Eyal does frame the dilemma faced by Jews in Europe—and by extension, other ethnic minorities—as “a triangle…one [point] is the extreme left-wing, one [point] is radical Islam, and one [point] is white racism.” And in that context, Hate certainly provides a visceral glimpse into some of the raw sentiments driving these angles.

Previous: Greek Mayor Flip-Flops Over Holocaust Memorial Unveiling

New Law Bans Holocaust Denial in Greece

The Frightening Reality for the Jews of France

Hannah Vaitsblit is an intern at Tablet.