Farewell Martin Landau, the Only Actor Who Could Save Woody Allen From Himself

A gifted actor who thrived on ambiguity, he made ‘Crimes and Misdemeanors’ a masterpiece

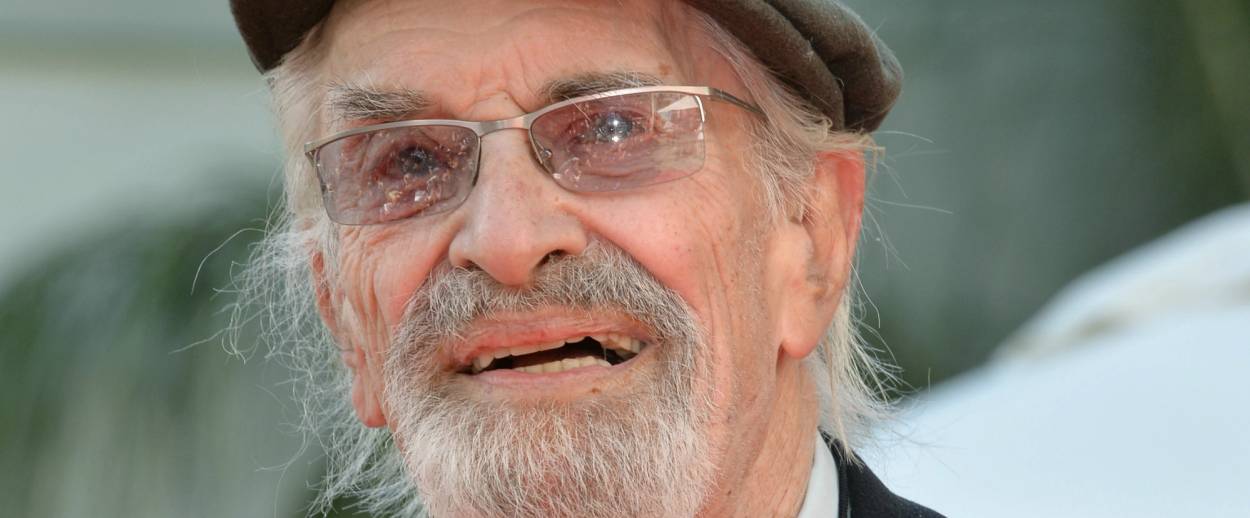

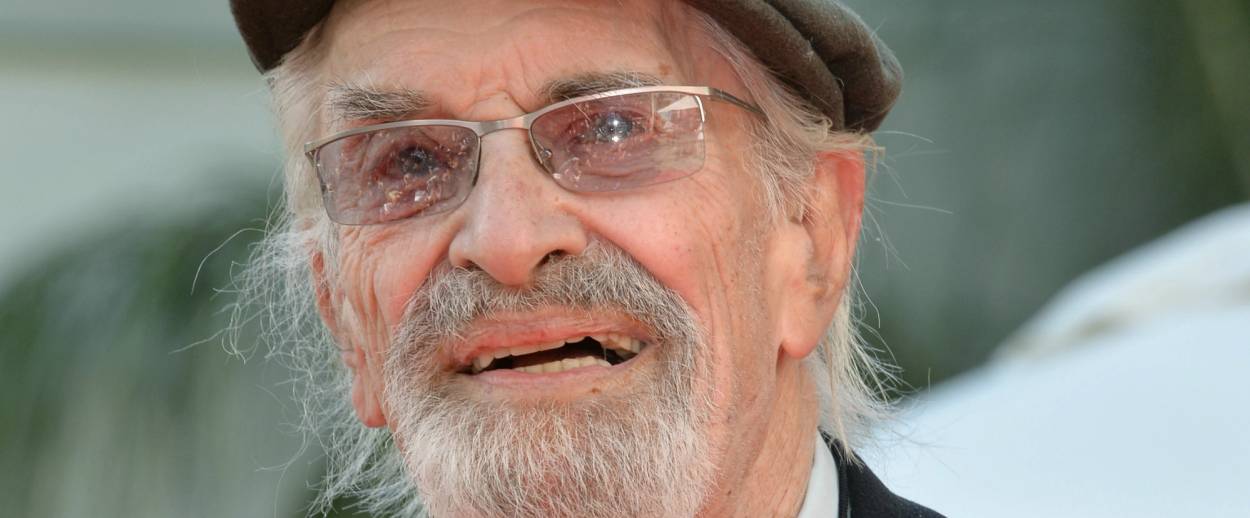

Martin Landau, the Academy Award-winning actor whose virtuosic career spanned seven decades and included collaborations with some of the most lauded directors in history, died Saturday at the age of 89. The cause of death was “unexpected complications” (to extent that any complications can truly come as a surprise at the end of one’s ninth decade of life) following a brief stay at UCLA Medical Center.

Landau was among the last of a (literally dying) breed, the kind of intense and versatile actor about whom it can be said: “He was born in 1928 in Brooklyn, to a family of working-class Jewish immigrants” (His father, an Austrian-born machinist, struggled to save relatives trapped in Europe as the Nazis came to power.) His acting career, after an early detour as a visual artist and illustrator—at 17, the multi-talented Landau was hired as the editorial cartoonist at the New York Daily News, a position he quit after 5 years to pursue a career on the stage—followed the typical trajectory of a performer of his time and place: summer stock, the Actor’s Studio (where it seems he, like many of his cohort, briefly romanced Marilyn Monroe, cementing her taste for craggy and saturnine Jewish intellectuals; see Miller, Arthur); a few appearances on television on shows like Molly and Playhouse 90, the highbrow peak TV of the time; and finally, the breakout movie role that would cement his place a recognizable Hollywood character actor for the next 60 years.

And it was a doozy: Landau played James Mason’s sinister henchman in North By Northwest, perhaps the greatest of Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thrillers, and rendered unforgettable for the way Landau chose to play him: as a gay man attracted to his scheming boss. In the homophobic 50’s, this may have seemed like just one more signifier of his dastardly character’s villainy, but Landau’s portrayal also betrayed a core of humanity and vulnerability in a role that could easily have come across as just another nondescript screen heavy. Even bad guys have complex emotions, Landau understood, and desires beyond mere evildoing. Bad guys are people too.

The willingness to exist within this moral ambiguity was key to Landau’s strange and compelling screen presence: at once sinister but human, forbidding yet avuncular, with the dark brow and angular cheekbones of a dangerous brooder and the wide, crooked grin of a shy Jewish boy from Brooklyn. These qualities were put to great use by the director Tim Burton, himself a master of lovable darkness (Burton directed Landau in his Oscar-winning turn as aging horror icon Bela Lugosi in 1994’s Ed Wood) but find their greatest expression in what was perhaps Landau’s greatest role: the morally compromised ophthalmologist Judah Rosenthal in Crimes and Misdemeanors. In what is arguably Woody Allen’s greatest, or at least most accomplished and philosophically complex film, Landau inhabits his character, an outwardly respectable pillar of his community who hires a hitman to dispose of his troublesome—and, uniquely for Allen, more or less age-appropriate—mistress (a searing Anjelica Huston), and to his shock, suffers no meaningful retribution for his heinous deeds, leading him to conclude that the concept of sin is a fallacy and that the God of his Orthodox Jewish upbringing is a powerless one, if He even exists at all (Allen would revisit this basic story, stripped of its Jewish context, in his lauded 2005 “comeback” Match Point, with Irish hottie Jonathan Rhys Myers in the Landau role.)

The film wrestles with Allen’s basic mission statement, or some version of his infamous statement: “The heart wants what it wants,” which also applies to his controversial relationship with his sorta-stepdaughter Soon-Yi Previn, before lapsing into self-parody and obsessing over ways for middle-aged and older men to justify their inappropriate relationships with teenage girls. But it’s Landau’s searing portrayal of an otherwise decent man’s cold-blooded rationalization of what he knows to an immoral, even an evil, act, that transcends Allen’s usual college-kid philosophizing. Landau is utterly devoid of the knowing schtickiness that often infects the performances of otherwise great actors the moment they are handed one of Allen’s famously partial scripts, particularly a “Jewish-y” one. Instead, he attacks the character as a deeply flawed human being, who has a good reason for everything he does: his mistress is threatening to expose their affair to his wife, which would explode his carefully managed life. In his mind, then, he is justifying his actions as a trade between the life of one unloved woman for the happiness and well-being of another, even as, deep down, he knows better.

In the film’s final moments, Landau as Rosenthal gives us what may be his most chilling scene in a career that was full of them: having orchestrated a murder, gotten away with it, and worked through his guilt, he is now nothing but a nice Jewish doctor who has lived an enviable life and is loved and celebrated by everyone in it. That this rings as such a stinging indictment of both masculine entitlement and what American Jewish culture deems as “success” is entirely due to Landau having such a profound grasp of the malignancy of both; that Allen never again drew such effective water, despite his numerous trips to the same misanthropic well (see Deconstructing Harry, or the execrable Whatever Works) is a mark of Landau’s genius. They don’t make ‘em like that in Brooklyn anymore, but at least they once did.

Rachel Shukert is the author of the memoirs Have You No Shame? and Everything Is Going To Be Great,and the novel Starstruck. She is the creator of the Netflix show The Baby-Sitters Club, and a writer on such series as GLOW and Supergirl. Her Twitter feed is @rachelshukert.