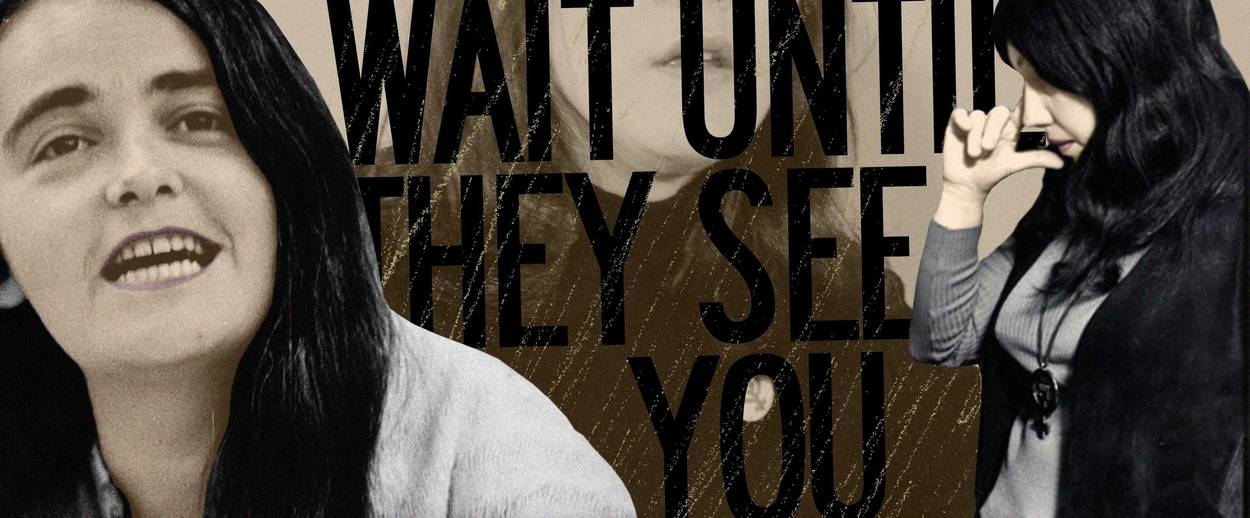

Feminism and Fame

In the third of four excerpts from Phyllis Chesler’s ‘A Politically Incorrect Feminist,’ fear of flying

I had chosen to work with Betty Prashker, who was Kate Millett’s editor at Doubleday.

After Kate read Women and Madness, she immediately endorsed it, which made me very happy. This was new—women being able to blurb each other’s books in a way that impressed publishers. I called Kate to thank her. We made plans to get together.

I visited Kate at her farm near Poughkeepsie, New York. She viewed the land she had bought in a 19th-century kind of way, as the only thing that one can count on. Kate planned to grow Christmas trees and sell them to pay the taxes and for renovations. The property had three big buildings that needed upgrading and perpetual care. Kate also envisioned the place as a summer retreat for women artists, who would work on the farm half the day (mowing, planting, building) and on their own work the rest of the time.

Kate and I had a wonderful evening. She grilled thick steaks and opened bottle after bottle of wine, and we laughed about “our movement.” It was a bit like being in a college dormitory or like having a sister, something I knew nothing about.

We were up quite late. Kate said: “They may think they’ve seen everything, but wait until they see you. You’re something else.”

Our dear friend Linda Clarke tells me that Kate told her: “Phyllis is going straight to the top.”

How much pleasure I took in being able to pledge the sorority of our first feminist icon. Icons are mesmerizing. Kate was there first, right on the cover of Time magazine. Kate had died for our sins, so to speak. Kate knew how to boss women around, but all the bullying she’d done could not compare with how prominent anti-feminists mocked her and how lesbian feminists had bullied her into coming out as bisexual and/or as a lesbian. Kate also suffered resentment, envy, even hatred because she was famous. She wrote about this in her next book, Flying.

A year later, our editor, Betty, followed me into the bathroom and urged me to persuade Kate to remove “all the lesbian material” from Flying, because with it the book was not going to fly at Doubleday. I told her I couldn’t do that. Betty probably feared that the lesbian content would doom the book. How could she have known that a gay and lesbian movement would soon become a major and visible force fighting for equality?

Perhaps Betty also did not like the self-indulgent and demanding voice of the book, which I found Joycean and was the very thing that I admired about it.

In 1973, my friend Erica Jong’s comic novel Fear of Flying was published. It garnered John Updike’s effusive praise and began its path to best-sellerdom. Kate lost Doubleday and moved to Bob Gottlieb at Knopf, where the book was published in 1974 and bombed. I love both books.

***

Before the 1970s, most women who worked in publishing were secretaries and editorial assistants, were grossly underpaid, and watched as young man after young man was promoted to editor. Reviews of women’s books were not as frequent or as positive as reviews of books by men; more men reviewed books in mainstream and intellectual media than women did. Eventually feminists protested this and made some headway, but all too soon editors began to tap feminists who were at loggerheads ideologically to review each other’s works, which they were only too happy to do.

In the 1960s, women did not write feminist books. Women wrote some best-sellers, but mainly they were cookbooks or about sex, not liberation. Helen Gurley Brown’s Sex and the Single Girl (1962) and William Masters and Virginia Johnson’s Human Sexual Response (1966) were sensations. Betty Friedan’s landmark book The Feminine Mystique (1963) was not an immediate best-seller.

However, from 1970 to 1975, “dancing dog” feminists (the phrase is Cynthia Ozick’s) turned out book after book. We were sought after, written up, interviewed, and could do no wrong. Suddenly our work was celebrated, and publishers or other writers gave us book parties.

At a book party for Alix Kates Shulman’s 1972 novel Memoirs of an Ex-Prom Queen, Vivian Gornick rushed up to me, breathless and panicked.

“What does she want from me?” Vivian pleaded. “What am I supposed to do?”

“She” was the lesbian activist Rita Mae Brown.

Rita Mae casually strolled by and said: “Just look at her beautiful green cat eyes. I can’t stop looking at them.”

She was completely and defiantly oblivious to the panic she was causing.

Rita Mae, a daughter of poverty, went on to publish Rubyfruit Jungle, live briefly with the tennis star Martina Navratilova, settle down, fox-hunt in the Southern countryside, and write best-selling detective novels with her cat, Sneaky Pie Brown.

***

I probably would have written my first book no matter what century I’d lived in. That I did so as second-wave feminism was gathering power nationally ensured that the book had an audience, one that instantly embraced its ideas.

Why this subject and not another one? Did I have mentally ill relatives? Of course—who doesn’t? But most people don’t get up one day and write Women and Madness in order to understand their relatives.

I’m not exactly sure what I did the summer before Women and Madness arrived in bookstores. I believe I was at the MacDowell Colony for a few weeks, completing my interpretive essay about the psychohistory of Amazon warriors.

I do remember renting a house in Lomontville, New York, not far from the Ashokan Dam, later that same summer. I loved living alone. It was a sacred time. I finished the introduction to Women and Madness there and I clearly remember stepping out late one night, looking at the moon, and knowing that I might change the world—and my own world, too.

Oct. 1, 1972. Publication day. My editor Betty sent me a red leather-bound copy of my book. I have it still. (I’ve always wanted to bind one copy of each of my books in leather, but it’s too expensive.) Judy Kuppersmith, my Bard College and New School buddy who had joined me at Richmond College, gave me a surprise birthday party. When I look at the photos today, I grow misty eyed.

Here’s Alix Kates Shulman, holding her fork aloft, tossing her head back, vivacious. Here’s Gloria, sitting on the floor, wearing jeans, our heads touching. Here’s Tina Mandel, one of the founders of Identity House, which pioneered peer counseling for gay people.

Gloria gave me a ring fashioned from a Greek coin depicting the goddess Athena; women were responding to my reintroduction of divinity in female form in Women and Madness. Psychologically, this seemed empowering. Wouldn’t learning that people once worshipped goddesses, that the divine is female as well as male, and that God has a female or feminine side transform women’s self-esteem and how women are seen and experienced?

***

Catharine Stimpson was a professor of literature and a fiercely ambitious feminist academic. Stimpson taught at Barnard and lived on the Bowery near Kate Millett. Stimpson was also the founding editor of the academic journal Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society. She went on to serve as the president of the Modern Language Association, an adviser for the MacArthur “Genius” Awards, and dean of the graduate school at New York University. Stimpson generously insisted on giving me a book party for Women and Madness because, like Kate, I was becoming hot.

The party passed by in a blur—an author is hardly present at her own book party. She is in an altered state but is expected to greet everyone like a politician running for office.

Stimpson’s loft was dark but large. My editor Betty was there, as were several potential reviewers of the book. Two former lovers and my family also attended. My relatives sat stiffly together, the women clutching their handbags. The party was filled with feminists. My best buds Barbara Joans, Barbara Chasen, and Judy Kuppersmith were there, as were the actress and film and theater buff Anselma Dell’Olio, the lawyer Emily Jane Goodman (with whom I later co-authored a book), the psychologists Leigh Marlowe and Elaine Stocker, and all my feminist psychology colleagues from Richmond College.

Jill Johnston was outside, picketing. She was wearing a sandwich board that said “certified insane.” I couldn’t argue with that, but I kept inviting her to come in. Remember: Jill had a thing against doctors writing about mental illness.

The Southern writer and lesbian lush Bertha Harris (whose 1976 novel Lover is very Djuna Barnes–like) was drunk and punched Dr. Sal Maddi, who was reviewing my book for Saturday Review.

Nice going, sisters.

This Brooklyn girl, who once wore hand-me-down clothes and allowed herself to be so badly treated by men, had arrived. Nothing compares to celebrating the publication of your first book.

***

I was asked to speak at a Radcliffe Conference on Women and Mental Health and at Harvard’s Graduate Program in Community Psychiatry. At the time, I thought that if I had been a man, this might have meant I was being considered for a teaching appointment.

Within a week of my lecture, four women physicians quit their residencies in psychiatry. They wrote me to say that my lecture had changed their lives. I attended a party in Cambridge at the apartment of Dr. Paul Rosenkrantz and his wife, Barbara, which overlooked the Charles River. (Paul was not associated with Harvard, but Barbara was an associate professor of history of science and in 1974 became the first woman to hold the position of house master at Harvard, with Paul as co-master.) Together with Dr. Inge Broverman, Paul had published an important study documenting sex-role stereotyping in mental-illness diagnoses, and I had cited it in Women and Madness.

Suddenly Adrienne Rich, the poet, someone I had never met, was standing before me.

“You have just revolutionized mental health for women,” she said. “I have come to pay my respects.”

I was floored. We talked briefly, and then I said, “The New York Times has not and probably will not review it. At least, that’s what my editor thinks.”

“Oh, really,” she said. “Well, we’ll see about that.”

At the end of November, her scathing review of Midge Decter’s The New Chastity and Other Arguments Against Women’s Liberation in the New York Review of Books mentioned my work.

Phil Donahue (who would marry Marlo Thomas) was the Oprah of his day. He featured feminists like me for a respectful hour of conversation. He was a wonderful interviewer.

Women began writing to me.

The book had been out for a month, with reviews in Kirkus Review, Publisher’s Weekly, Library Journal—all industry publications—and in Saturday Review, Psychology Today, the Village Voice, and the New Republic. The New York Times had still not reviewed it.

To the glitterati, receiving a positive review in the Times is the equivalent of being knighted or kissed by the gods. Books by women—feminist books by women—were still viewed as strident, man-hating, hysterical, dancing-dog sensations, not the stuff of which classics were made.

In a season when some other feminist books had received six-figure sums for paperback rights, Women and Madness did not. Doubleday had decided that without a major review and incredible sales, it would be smart to hold the paperback auction before people lost interest.

Doubleday was right. It sold my paperback rights for a song—and it might have been the best or only offer in town. Still, I was so distraught that I called Betty, my editor, late at night, weeping. I had no perspective. I had been planning to donate money to various feminist causes and now I couldn’t.

Well, maybe it was for the best. At that point I realized, more than ever, that I’d better hold on to my job. Otherwise I would not be able to afford my writing and my activism.

About a month later, Adrienne Rich’s long and glowing review of Women and Madness appeared on the cover of the New York Times Book Review. This may have been the first feminist work of my generation to be so garlanded.

Sales soared and my editor smelled a winner. Yes, a single newspaper had that much gatekeeping power. It still does.

Adrienne: Wherever you are, I am in your debt, as are the millions of women whose lives were changed because your review meant they would now read my book.

I paid it forward when, 20 years later, I reviewed Judith Lewis Herman’s important book Trauma and Recovery in the pages of the New York Times Book Review.

***

Within a month, reviews of Women and Madness appeared in newspapers in Boston; Charlotte, North Carolina; Chicago; Cincinnati; Cleveland; Long Beach, California; New York City; Philadelphia; Phoenix; Pittsburgh; San Francisco; Seattle; and Vancouver—and in Time, the Guardian, and in dozens of other places.

Lecture agents clamored to represent me. University student groups asked me to speak. Despite these one-night stands, I would never receive an offer to join the faculty of any of the universities where thousands of students—mainly female students, and only a handful of male students or male faculty—crowded to hear me preach the word.

I was becoming famous—I was famous. Yet I didn’t like the loneliness, the demands, and the envy, or that mere fame was not the same as power. Although fame glowed, it was problematic. Being famous certainly helped my writing and lecture career. Sometimes it also meant being recognized on the street, and it always meant being recognized in feminist circles. Strangers related to me as if we were intimates. People who knew me pulled away. Perhaps they felt that I had—or would soon—abandon them for other famous people, that my fleeting success made them see themselves as lesser beings, as if I had somehow “shown them up.” Perhaps they could not forgive me for having been recognized when they had not been. Kate Millett writes about this phenomenon in Flying, a book that had not yet been published.

A life on the road made me feel harassed, not flattered, especially when young women tried to jump into my bed. It drove me to drink. For a few years I drank to fall asleep in motel and hotel rooms. I was so far from home—this was my home, but I was so alone, so set apart, by my admirers: I was not one of them; I was the sacrifice. My reaction to fame was, to paraphrase one of Martha Shelley’s poems, it’s too late to take it back but I’m not sure it’s an improvement.

This is the third of four excerpts from Phyllis Chesler’s A Politically Incorrect Feminist. Read the others here.

Phyllis Chesler is the author of 20 books, including the landmark feminist classics Women and Madness (1972), Woman’s Inhumanity to Woman (2002), An American Bride in Kabul (2013), which won a National Jewish Book Award, and A Politically Incorrect Feminist. Her most recent work is Requiem for a Female Serial Killer. She is a founding member of the Original Women of the Wall.