Foreplay

A proposed San Francisco ballot measure prohibiting circumcision arises from a debate over ritual, sexuality, and identity. What’s become an American norm might soon again be a mark of difference.

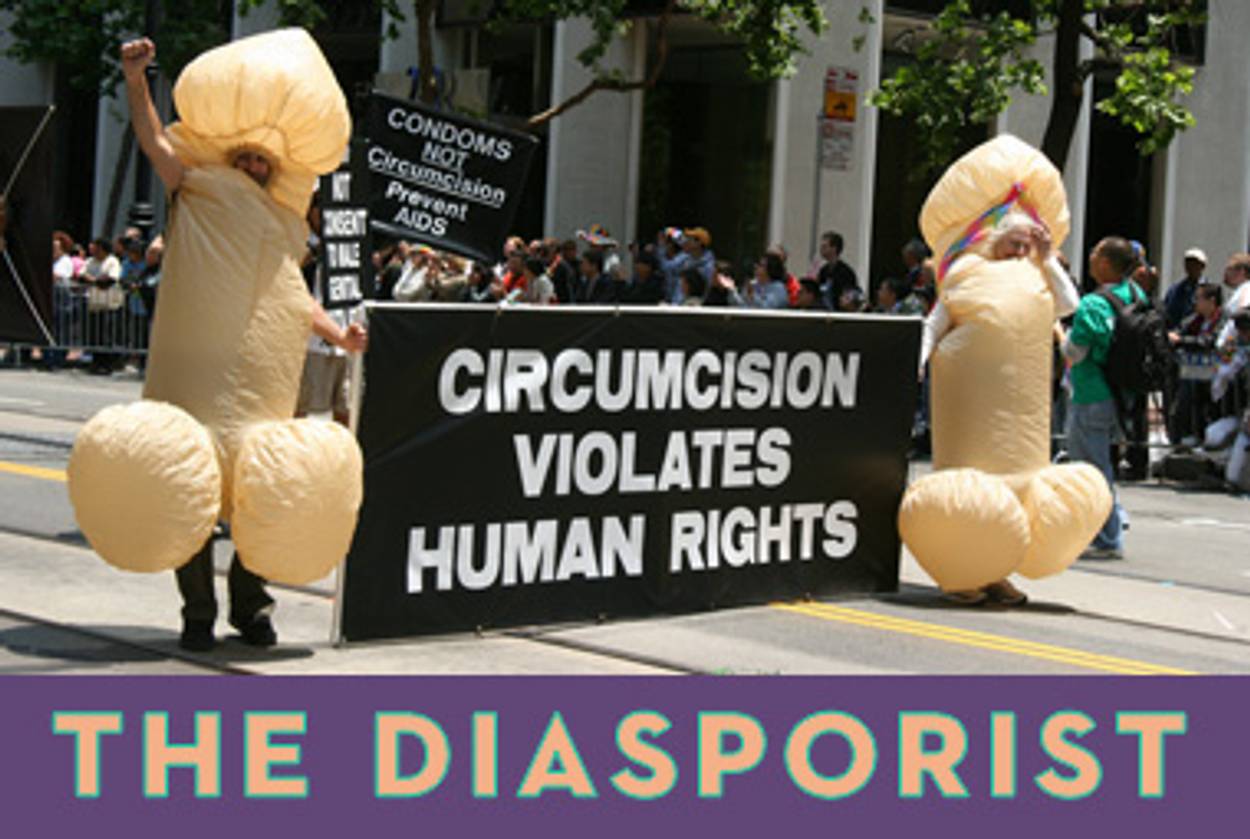

This November, San Franciscans will likely be asked to vote on a measure criminalizing circumcision and imposing thousand-dollar fines and even jail time for violators. With petitions for ballot initiatives due in April, the Committee Opposing Forced Male Circumcision expects to have well over the 7,168 signatures that it needs to get on the ballot. Thus the Bay Area, already a hotbed of anti-circumcision activism, is about to become roiled in a debate over foreskins. “Once we qualify for the ballot, I’m hoping we can enlist people from across the world to come to San Francisco and help us do the legwork,” says Tina Kimmel, one of the activists behind the initiative. Even if they lose, they’re relishing the attention. “It’s wonderful that we’re getting so much press,” she says. “There’s no such thing as bad publicity.”

In a way, it’s odd that San Francisco, of all places, would be the site of such a challenge to multiculturalism. Male circumcision, after all, is a hugely significant rite in both Judaism and Islam—indeed, one salutary result of San Francisco’s ballot initiative is the way it has momentarily united Jews and Muslims in their opposition. But while the removal of the foreskin has long signaled a Jewish boy’s entry into the community, for circumcision opponents, it signals the intolerable toll that custom and clan take on the individual. A complex debate about individual versus community rights hinges on that single primal cut.

That complexity, though, is often eclipsed by hysteria. Anti-circumcision activists—or “intactivists,” as they rather cringingly call themselves—are a lot like Free Mumia people. They have a point, but their self-righteous intensity does little for the credibility of their cause. They regularly compare male circumcision to the clitoridectomies performed on girls in parts of Africa. Male and female circumcision are “hands down exactly the same thing,” says Georganne Chapin, executive director of Intact America. Marilyn Milos, founder of the National Organization of Circumcision Information Resource Centers, compares a boy’s dawning realization of his foreskinless state to a girl whose parents tell her that “one in eight girls is going to develop breast cancer, so we decided to cut yours off.” Kimmel insists that circumcision is on the way out, just as “stoning adulteresses to death has gone by the wayside as people become enlightened.”

There’s something at once poignant and unsettling about the amount of pain and rage men in the movement express over their own circumcisions. On one forum devoted to foreskin restoration, a man describes how, only a week earlier, the scope of his loss had hit him, waylaying him with “resentment, grief and anger” that leaves him in tears. His post was titled, “Will I ever feel complete?”

Mark Reiss, a retired physician in San Francisco who grew up in an Orthodox Jewish home in New York, had an epiphany about the horror of circumcision when his first grandchild was born. “When I realized what I had lost and will never get back,” he says, it was traumatic. He’s convinced that having sex with a foreskin is inconceivably exquisite. “I will have never experienced a full sexual experience,” he says. “To talk to circumcised men about the intact state and what the full blown sexual experience is like, is like talking to a blind person about seeing.”

It’s hard not to suspect that such grief is about something more than a missing foreskin. Circumcision, after all, is a potent metaphor for parental betrayal and emasculation. The anti-circumcision movement gives men a powerful explanation for the sense of loss and declining potency that usually attend aging. Milos says she most often hears from men in their 40s, who begin having trouble with sexual performance and ask, “What’s happened to my penis?” One explanation may be that they’re suffering the effects of their circumcision. Another is that they’re getting older.

Scientifically, the results of research about circumcision and sex are mixed. There have been numerous studies of men who have been circumcised as adults. In some, the majority report that sex improved afterward. In others, the majority said sex got worse. The “decrease in penile sensitivity that resulted from circumcision bordered on statistical significance,” reported a 2002 study in the Journal of Urology. But a 2005 study in Urologia Internationalis found that 38 percent of men found “[p]enile sensation improved after circumcision,” while 18 percent said it diminished, with the majority reporting no change.

Yet even if circumcision is not usually experienced as the life-destroying mutilation critics describe, there is something strange about the custom’s persistence, particularly among pork-eating, Sabbath-ignoring secular Jews. “Circumcision has always been a procedure in search of a justification,” says Chapin, and she’s not wrong. In the Jewish tradition, of course, the brit milah lies at the very core of God’s covenant with his people. But as Jews grew more secular, ancillary reasons for circumcision emerged. In the Victorian era, it was said to prevent masturbation, which is one reason that gentiles in both the United States and England adopted it. For modern liberals, the idea of circumcision as an impediment to onanism is, if anything, a strike against the practice, evidence that it really does impede sexual pleasure. But as early reasons for circumcision have been eclipsed, new ones have emerged, particularly the procedure’s role in protecting men against sexually transmitted diseases.

Still, the medical evidence is ambiguous enough that the American Academy of Pediatrics makes no recommendation in either direction. Reason alone does not explain circumcision’s survival. There are still vestiges of religion involved, things that don’t quite make sense in secular terms.

It’s absurd to compare male circumcision to female clitoridectomy. Yet when doctors, in an attempt to mitigate the harm of female circumcision, have proposed introducing forms of female genital cutting that are less severe than male circumcision, they’ve been attacked for capitulating to barbarism. Last year, for example, the American Academy of Pediatrics proposed allowing doctors to perform “ritual nicks” on baby girls to satisfy their parents’ demands for circumcision, but the outcry was so great that the AAP had to withdraw the policy. If merely pricking a baby girl’s genitalia is wildly controversial, but cutting a boy’s genitalia is routine, it’s because of the very different civilization meaning we ascribe to the two acts.

And in that sense, circumcision contravenes some essential liberal values. It is evidence of a sexual double standard. It’s a painful and bloody rite whose purpose doesn’t lie in any immediate medical need. It marks a boy as a member of a group in a way that precedes his own decision-making, challenging the individualistic belief in a self-created identity.

Indeed, in the future, circumcision will likely once again become a mark of Jewish—and Muslim—difference. Non-Jews seem to be moving away from it—last year, a researcher from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that in 2009, only 32.5 percent of newborn boys were circumcised in the hospital, down from 56 percent in 2006. In 2002, Sweden passed a law regulating circumcision, mandating, among other things, that a doctor or nurse administer anesthesia. Most Swedish doctors refuse to perform the cut, seeing it as a violation of a child’s rights, and some politicians want to ban it for children under 18. Last year, the Royal Dutch Medical Association put out a statement calling for a “powerful policy of deterrence,” arguing, “Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors conflicts with the child’s right to autonomy and physical integrity.”

Some progressive Jews are turning their backs on it as well, embracing an alternative ceremony known as a brit shalom. Reiss runs a website that lists rabbis and cantors nationwide who will preside over the ritual, and he is about to officiate at one for the first time. “It’s happening more frequently as the generic population in the United States circumcises less,” he says. Nor is this an entirely new phenomenon. As he points out, “Jews have been rebelling against ritual circumcision for centuries. In Germany in the mid-19th century, there was a group of reform rabbis who wrote papers on it.”

As the practice falls out of favor in the secular world, the circumcision wars will probably only get more heated, because they’ll be about a minority religious custom, not an American norm. If male circumcision comes to be seen as harmful, after all, it will be hard to justify it on religious grounds alone without also justifying less-invasive variants of female genital cutting. At that point, proposals like the one in San Francisco might seem less preposterous and more, well, cutting edge.

Michelle Goldberg is a senior contributing writer at The Nation. She is the author, most recently, of The Goddess Pose: The Audacious Life of Indra Devi, the Woman Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West. Her Twitter feed is @michelleinbklyn.

Michelle Goldberg is a senior contributing writer at The Nation. She is the author, most recently, of The Goddess Pose: The Audacious Life of Indra Devi, the Woman Who Helped Bring Yoga to the West. Her Twitter feed is @michelleinbklyn.