About a year ago, while it was originally on display at UNESCO’s Paris headquarters, the city of Paris decided to bring the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s traveling exhibition about Nazi propaganda to its City Hall gallery space, where its currently being shown. In the aftermath of the Paris terror attacks, the exhibition area’s staff believed the exposition would help to address concerns about ISIS by explaining how extreme political messaging can capture audiences and followers. However, by the exhibit’s unveiling last month, conversation in Paris had shifted from jihadist radicalization to the surge of the political far-right and its nativist messaging, which was coursing through Europe. As a result, the meaning of the same USHMM exhibit also seemed to shift—to a display about the lessons of propaganda vis-à-vis the rise of populism in France (and beyond); and not, as originally imagined, to only suggest similarities between the Third Reich and modern Islamist terror groups.

Anti-Semitism, the show suggests, may have appealed early on to a radical fringe more than the average voter. The Nazis’ rise to power came with a concerted barrage of anti-Semitic propaganda—from films to children’s board games, e.g. Campaign posters reproduced in the exhibition show messaging crafted to various concerns in tumultuous interwar Germany. Some feature Jewish caricatures, but one has simply a hand holding out a fistful of tools to the unemployed. A poster aimed at newly enfranchised German women presents the party as the defender of families. The Nazis also deployed the latest technology of their era. In 1932, Hitler became the first European candidate to travel between campaign stops by plane. He would frequently address the German public directly via radio, unmediated by the press (over which he also consolidated control).

“In a few years, [the Nazi Party] was able to go from obscurity to prominence,” said USHMM co-curator Steven Luckert, referring to the effectiveness of the Third Reich’s sophisticated propaganda campaign. “The same technology can be used,” he noted, for “communities to create counter-narratives to these extremist ones.”

The exhibit went up around the end of Donald Trump’s first week in office as U.S. President; it also debuted in Paris as Marine Le Pen, who wants to ban French Jews from wearing yarmulkes and having dual Israeli citizenship, led polls for the first round of the French presidential race. Both have platforms proposing limits to refugees, as do other rising right-wing parties in Europe. Both, moreover, stress the dangers of other types of immigration and a certain kind of nationalism. While not Nazi parties, their rise via campaigns laden with nativist, xenophobic rhetoric finds parallels in some of the messaging in the exhibit, which exhibit organizers leave to interpretation.

But the lens through which it is seen has clearly expanded. When the European version of the traveling exhibition made its first stop in Paris last year, the French paper Le Point titled its review, “What Daesh’s propaganda owes to the Nazis.” Last month, in an op-ed L’Express published by museum director Sara Bloomfield, she gave equal time to terrorist organizations and the far right.

The exhibition ultimately lands on the question of culpability. In the post-war period, the U.S. and France would arrive at different approaches to balancing free speech and its incumbent dangers. For example, the man behind Der Sturmer, a paper devoted to stories of Jewish misdeeds, was hung after World War II. A radio personality who shared similar messages but didn’t call outright for the murder of Jews was acquitted. The United States has tended to side with freedom of expression—what Luckert referred to as the “marketplace of ideas” approach—where it’s hoped the good will triumph over bad. In France, racist speech as well as Holocaust denial are punishable by fines or even prison time, although the application of these laws can seem uneven. French courts convicted Jean-Marie Le Pen, former leader of the Front National, for calling the gas chambers “a detail of history.” However, Marine Le Pen, his daughter, was acquitted of racist speech in 2015 over a comparison of Muslims praying in French streets to the Nazi occupation. The history in the exhibition, said Luckert, “raises questions about how you address [speech] in a society.”

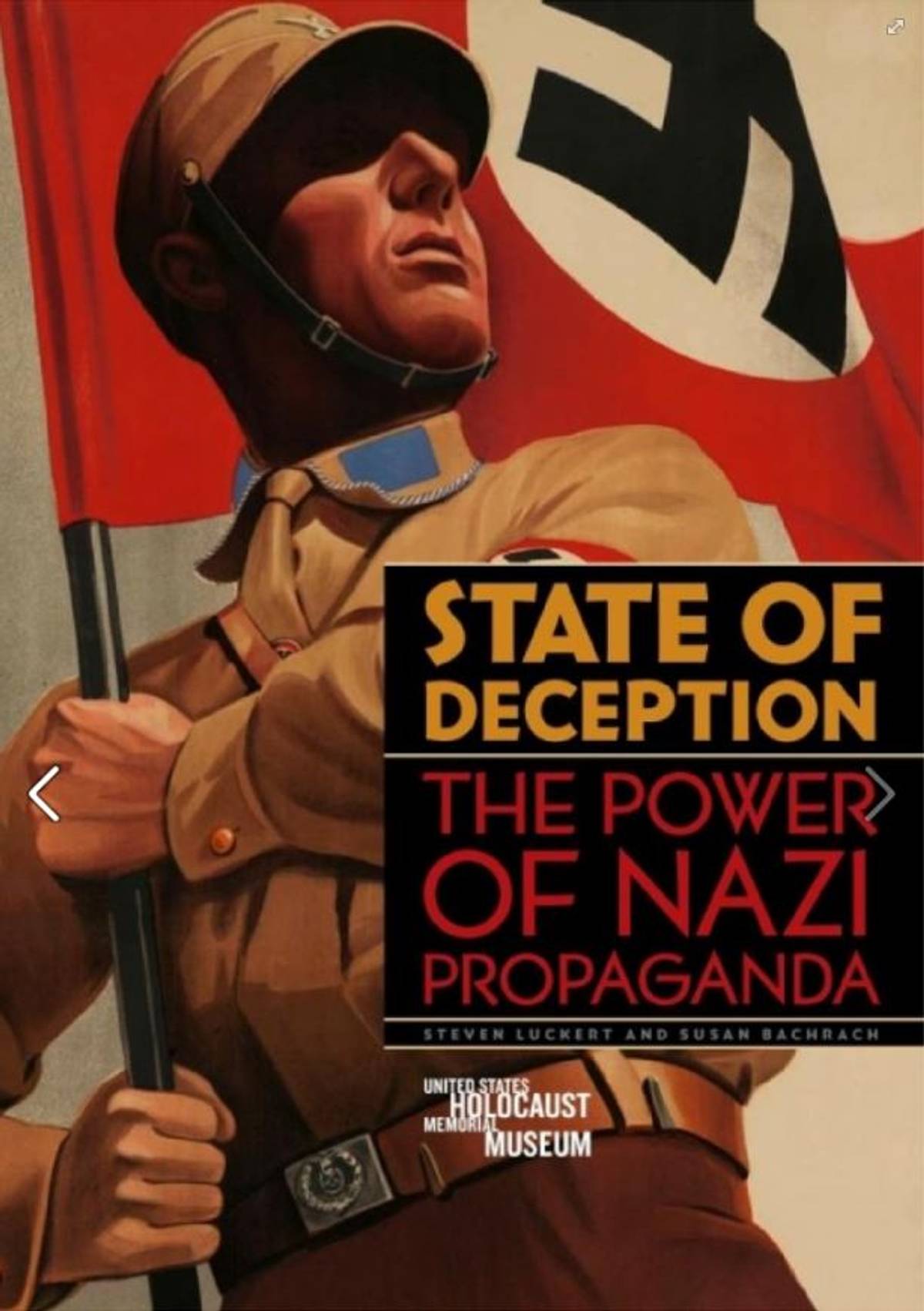

#USHMM‘s #StateOfDeception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda is now open in Paris. Learn More: https://t.co/X6mA8vBInG pic.twitter.com/1WgE4h32nZ

— US Holocaust Museum (@HolocaustMuseum) January 31, 2017

The exhibition, State of Deception: The Power of Nazi Propaganda, presented in French and English, will be at the Espace Paris Rendez-Vous until February 25. The American version of the traveling show is at the World War II Museum in New Orleans through June 18.