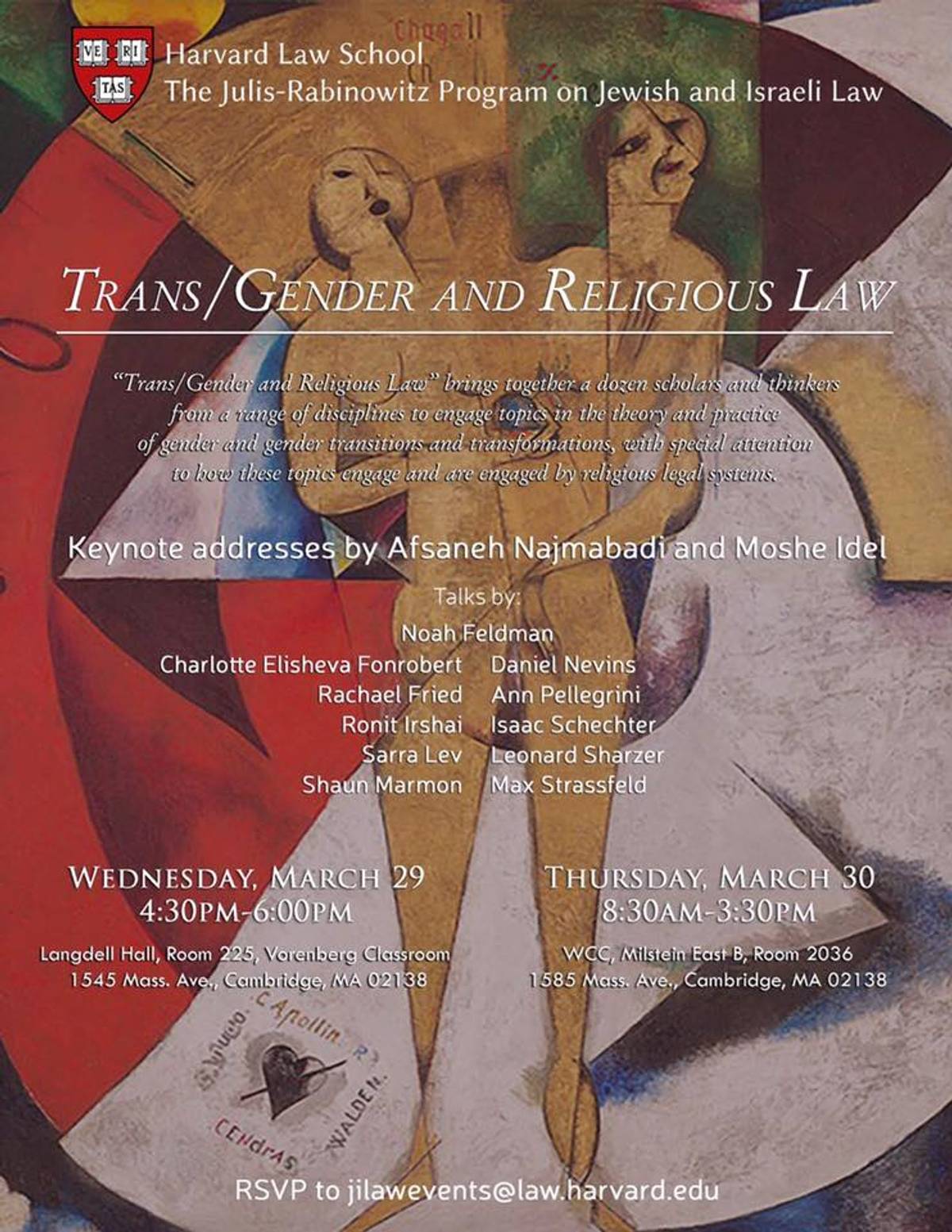

Harvard Conference Examines Jewish Law and Trans Identity

Held the week of Transgender Day of Visibility, academics and practitioners from all walks of life discussed the overlap of religious law and identity—and the human soul

It is, perhaps, rare for a Harvard constitutional law professor, a millennial social worker from New York City, and the leading living scholar of Kabbalah to be in dialogue with one another at an academic conference. It is even rarer for the common thread between presenters and practitioners alike at an academic legal conference to be the human soul. But at the Trans/Gender and Religious Law conference at Harvard Law School last week, this was exactly what occurred.

Hosted by the Julis-Rabinowitz Program on Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School, the conference broadly approached the question of transgender identity in religious text and experience. The bulk of the textual explorations and community organizers were associated with Judaism, though the conference brought together presenters with specializations in Judaism, Islam, and performance art and gender identity. The conference was held just before Transgender Day of Visibility, which has been internationally recognized annually on March 31 since 2010.

A major theme explored at the conference was how trans identity is discussed and acknowledged in the totality of Jewish texts–possibly “thousands of times,” according to Thursday’s keynote speaker Moshe Idel, a professor of Jewish thought at Hebrew University in Jerusalem. He said that much of the language used to discuss trans identity in the vast body of rabbinic literature written through the 20th century does not address the question of what he refers to as “a modern politically correct figure.” In layman’s terms, Idel said that rabbinic literature does not serve to validate an identity; the literature acknowledges a transgender person’s existence by talking about questions of fertility and obligation–not in terms of normalization; that is simply not the question that motivate the rabbis’ discussions. The first person to approach trans identity and halakha (Jewish law) in modern terms was Rabbi Eliezer Waldenberg who died in 2006 and was the rabbi of Jerusalem’s Shaarei Tzedek Hospital. He issued a contentious but practical ruling stating that gender reassignment surgery would render that person’s gender status in halakha to the gender to which they transitioned.

In a conversation with Tablet, Idel explained that many trans right activists use Jewish texts to explore and answer modern questions, an approach he disagrees with. Idel critiques that approach, which is held by fellow conference presenters, saying that asking questions about transgender identity–the language of which did not exist in Kabbalistic or Jewish rabbinical times–is off base. By imposing modern “glasses” onto the text, Idel argues, people are fundamentally misunderstanding rabbinic text, since they are imposing questions onto the rabbis that weren’t their primary concern.

Idel’s critiques were aimed at two presenters who preceded him: Rabbi Sarra Lev, a professor of rabbinic literature at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College just outside of Philadelphia, and Max Strassfeld, Assistant Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Arizona. Both speakers looked at rabbinic texts exploring the concepts of the androgynous person and tum-tum, often translated as intersex. Lev and Strassfeld both argue that the Jewish law and its texts are written in hyper-gendered terms. The nature of the speakers’ approaches were to both read the text for its own sake, and then also use text to answer modern questions.

More often than not, contemporary questions about trans identity in Judaism revolve around ritual practice. In Orthodox temples, for example, questions may manifest around which side of the mechitza a transgender person should sit, a topic discussed by Rabbi Steve Greenberg who directs Eshel, an organization serving the LGBT Orthodox community and their families. Rabbi Daniel Nevins, the dean of the rabbinical school at the Jewish Theological Seminary, noted that the Conservative movement might be concerned with how a transgender individual should be called up to the Torah, as the language used in this instance is typically gendered.

Professor Noah Feldman, the director of the Julis-Rabinowitz Program in Jewish and Israeli Law at Harvard Law School who emceed the conference, said he felt that the event was unique because participants talked about the soul–at a law conference. “You wouldn’t have a conference on trans law in the U.S. and invite the leading mystical figures of the culture to speak,” Feldman explained, “but that did make sense in the context of religious law. In religious law there’s always some backdrop of theology and metaphysics that might be there in the case of state law and often isn’t.”

During Wednesday evening’s keynote address, Asfaneh Najmabadi, the Francis Lee Higginson Professor of History and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality at Harvard University, also talked about the soul in Shia Islamic legal discourse and culture. Islamic literature, Najmabadi explained, discusses what happens when a soul doesn’t match with a person’s body. She explained how in these cases, the Arabic word that is used for soul is the word nafs, similar to the Hebrew word nefesh, as opposed to ruh, spirit, which is identical to the Hebrew word ruah. Nafs is the preferred formulation in this context of the soul. Her analysis and anecdotes are almost identical to the discussion of soul in Idel’s address during which he quoted Kabbalistic and Jewish legal masters like Rabbi Joseph Karo, the 16th century legal expert, and Rabbi Hayyim Vital, a Kabbalistic master in Safed, who talk of transmigration of souls and of souls having genders that do not match with the gender of their physical bodies.

In the weeks leading up to the conference, organizers received mild criticism on Twitter, as people questioned why there was only one out transgender speaker presenting at the conference. Tablet contributing editor Menachem Butler, who aided Feldman in directing the program, said organizers spoke with “multiple people who identify themselves as gender non-conforming or trans.”

As the conference shifted from academics presenting theory to activists, mental health professionals, and rabbis working with the transgender and Jewish populations, the Associated Press reported that North Carolina governor Roy Cooper had signed a measure rolling back—partially—the state’s contentious “bathroom bill.” Of the decision, the Charlotte Observer editorial board wrote that the “dishonorable” decision would leave “tens of thousands of citizens defenseless against discrimination,” including transgender people. The news event was a poignant reminder that the abstract theory in which the speakers had been engaged for the previous day and a half had practical, real world ramifications to the national legal community as well as religious ones.

Rachel Delia Benaim is a freelance religion reporter. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, and The Diplomat, among others. Follow her on Twitter @rdbenaim.