Everybody Goes to Harvard

The future of higher education in America is online

Eight years ago I rented a cheap apartment in an aging high-rise building along the parkway in the Bronx. The building was occupied primarily by the elderly and the retired and managed by a crew of sullen Greek cousins who spent much of their time in a ground-level office furnished with abandoned couches and a half-dozen birds in bright cages. This was a particularly despondent period of my life, not so much because of the peculiar overcast mood of the new digs but because I’d spent the past year or so as a participant-observer in the collapse of the grand media ecosystem that had prompted my coming to the city in the first place.

There was still work then, and I did find it, plopped in the same wobbly office chairs where previous generations went through the established routines of fact-checking printer-warm proof pages and typing out tables of contents for legacy magazines. If you stuck out the bad hours and low pay long enough, the magazines might bestow masthead positions where the pay was still bad, but which offered wider access to the trade network of paid gigs and handshake connections that had been the pulse of New York periodicals since the middle of the previous century. Yet, it was abundantly clear, even then, in an era that looks quaintly vibrant now, that the party was already over.

The constant nervous chatter whispered around copy desks and let loose at every happy hour was always the same, with different punctuation: jobs gone, salaries slashed, budgets cut, ad dollars at all-time lows, layoffs here, buyouts there. We didn’t need to be in the wheelhouse to see that the ship had crashed into the iceberg. We were watching the deck chairs slide toward the railing.

Some nights after staying late at the magazine where I was working, I’d take a cab home, while they still reimbursed for the expense. I’d walk past the door to the maintenance office, where the Greeks watched black-box cable with their feet up on metal-top desks, and I’d go up to my place to drink a beer and thumb through collections of essays and reported pieces, books by journalists and magazine writers who cut their teeth in the decades I’d formerly understood as a prelude to my own present moment.

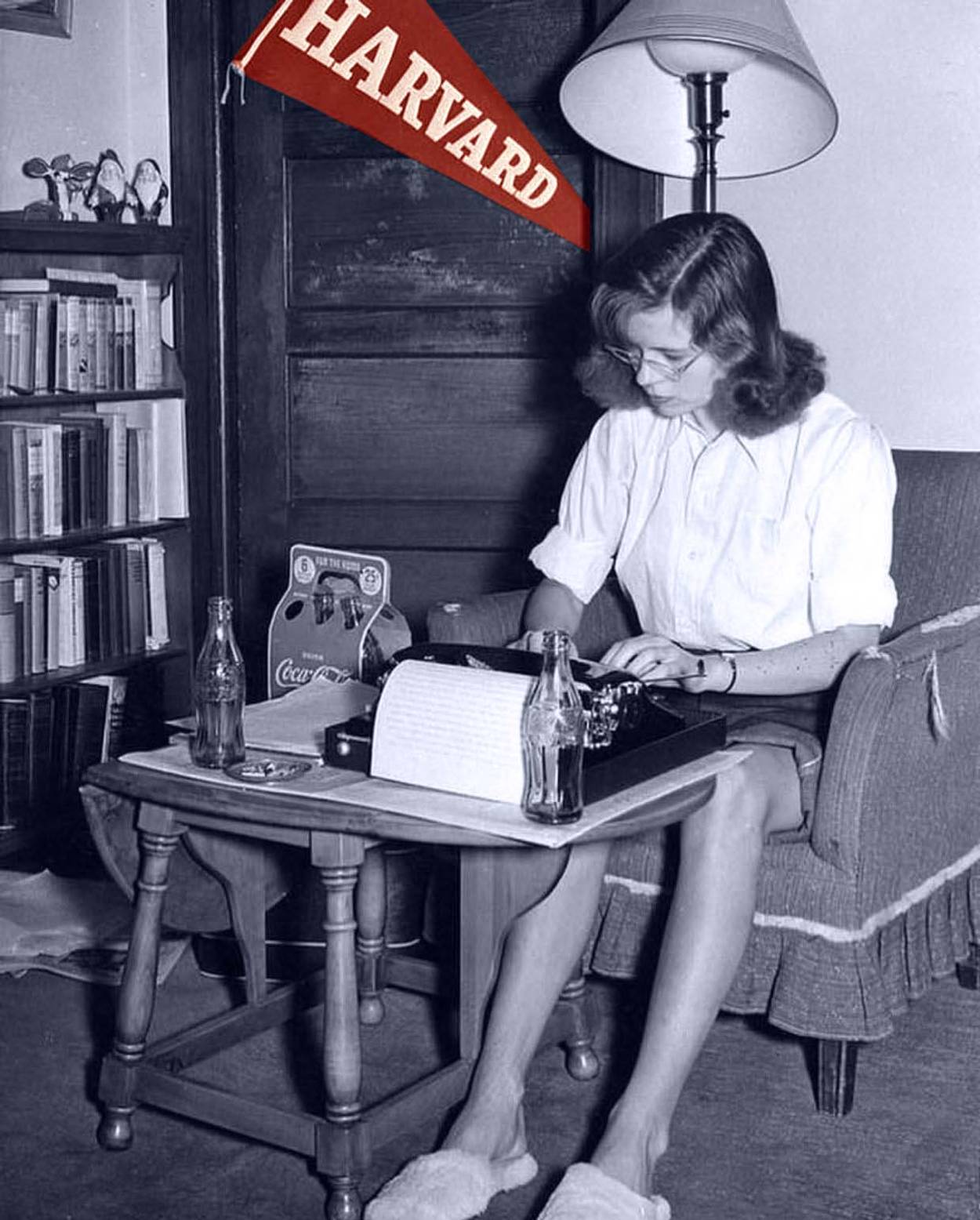

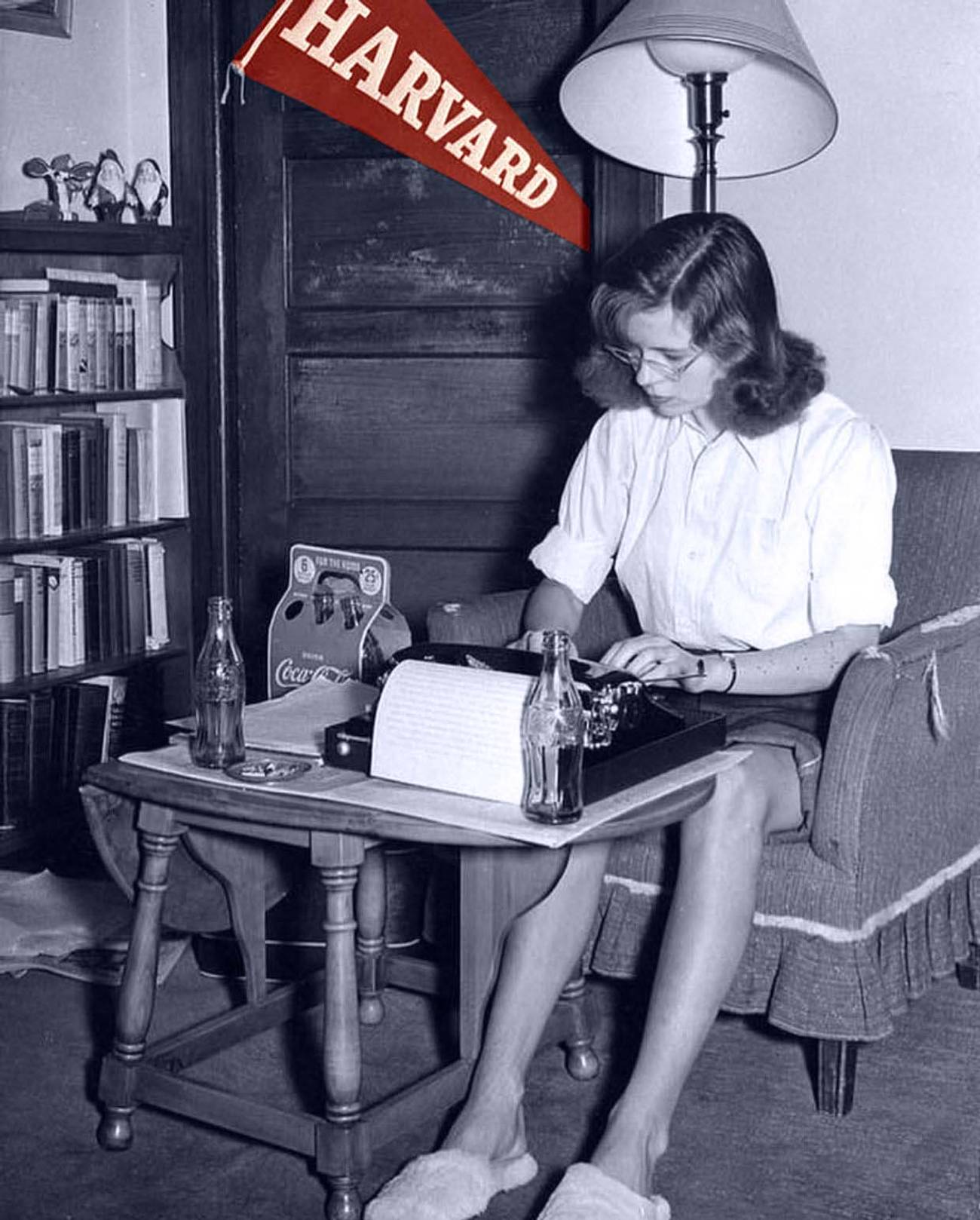

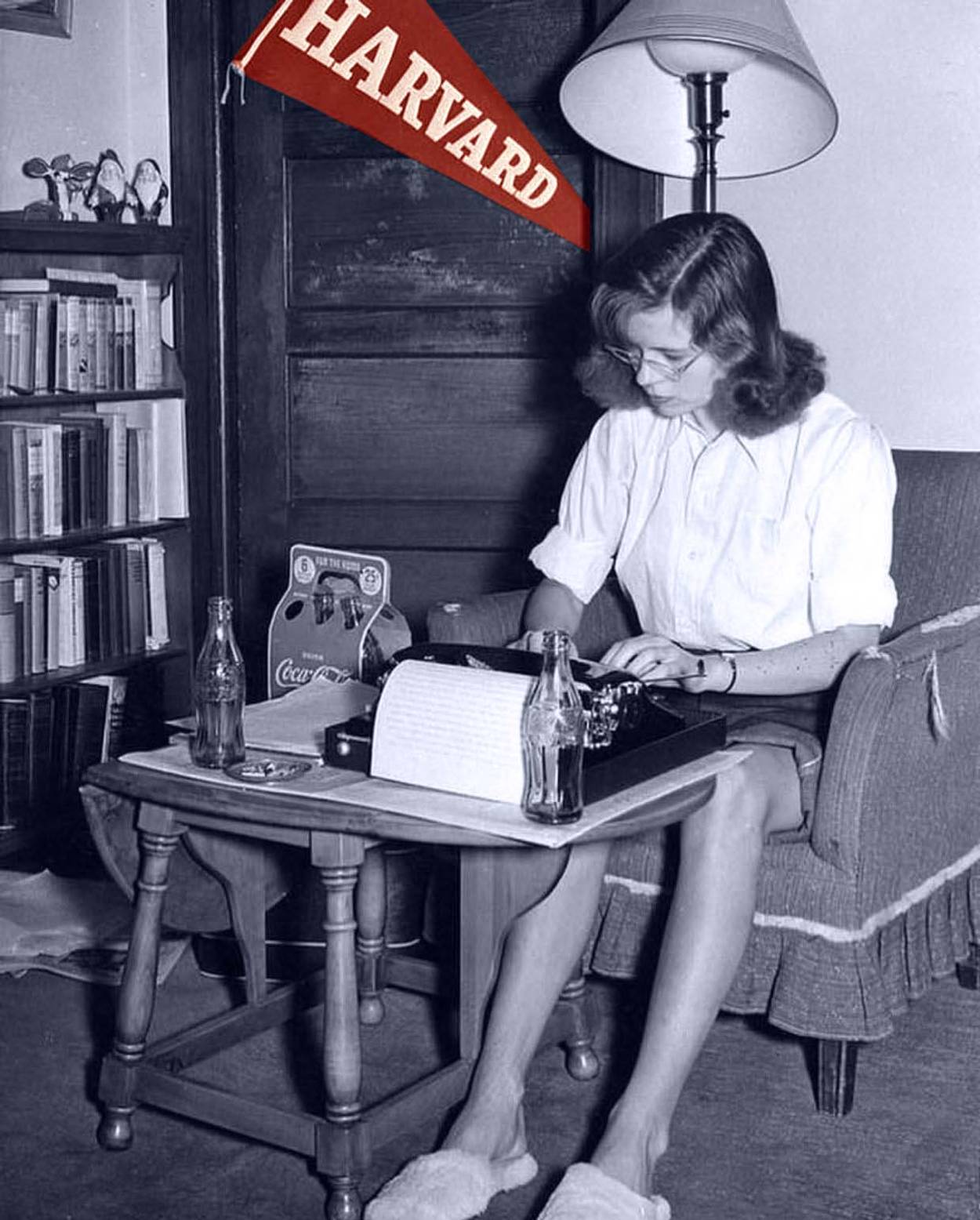

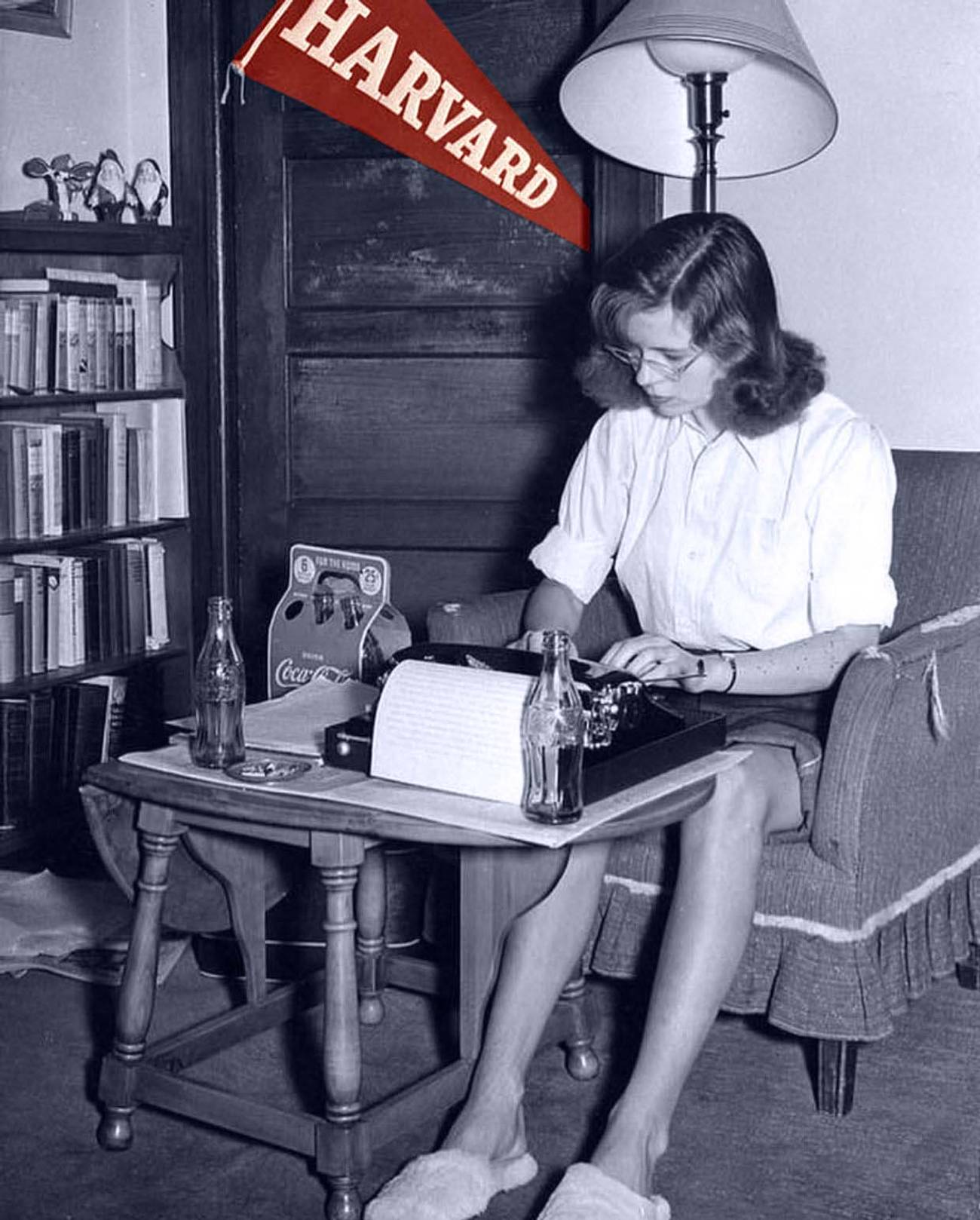

One of those nights, coming home late, I picked up a book I’d found tucked back on a shelf in the closet, left behind, I assumed, by the previous tenant. It was a flimsy, red soft-cover, the Tenth Anniversary Report for the Harvard Class of 2002. It was novel to me, a state-school kid trying to crack into this gated community of media, to read the peculiar voice, one that made even more clear to me that I stood outside some inner ring that benefited those within it. Here was a curated glimpse of that other life, in the form of a printed conversation among the class of 2002—350 pages of professional accomplishments and personal life updates, spouse’s occupations and earned degrees (included as accomplishments by proxy), written by the graduates in performative, genteel paragraphs. Taken together they formed a collective 10-year snapshot of how one class had managed their takeover of American institutions, politics, and finance.

“W and I were married in East Hampton … started my MBA program at Yale … I elected to start a venture capital firm … with a classmate from Yale and BF, the executive chairman of Ford Motor Company ... raised a fund ... offices in Detroit and Boston … quite happy with the progress we’ve made ... managed to squeeze in the San Francisco marathon ... purchased a home … loving life ... had our second child … last ten were pretty amazing,” went one of the dozens of entries.

Lost on me then was the extent to which these pages, many written by Silicon Valley’s new crop of founders, early employees, attorneys, and product engineers, were intimately tied up with the fortunes of the magazines and periodicals that were breathing their last breath in Manhattan’s increasingly shabby publishing offices. That understanding would come later. The narrative of the great disruption was still taking shape, of how the heralded tech unicorns, built by young Ivy League graduates, had devoured ad-supported publications, stripping them of their content and monetizing their audiences, giving back nothing in return.

Of course, the pillaging of a centurylong project of a print-centric magazine culture was not an abnormal occurrence. It was merely a verse in the chanted myth of late America, where inspired innovation and entrepreneurial imagination masquerades the wholesale raid of longstanding institutions, regardless of what social or cultural purpose they once served, in the name of cosmetic progress, for the sake of concentrated wealth and power.

I’d shelved the anniversary book away beside other reference titles on Sibley’s North American birds and Routledge chess openings. I thought of it again for the first time in years during the weird, languid days of the pandemic, when the mind freely wandered to rarely visited memories. Caught up along with everything else, the suspension of normal activities extended inevitably to the dense communities gathered on college campuses in the middle of their spring semester. The effort was led in early March by the University of Washington, and swiftly taken up by every other university, sending the nation’s 11 million undergraduates home to attend college remotely.

At Harvard, the transition from a campus-based institution to the virtual realm took some two weeks, and relied upon a management system for grades and administration as well as a suite of digital tools built by valley unicorns like Slack and Zoom to move 5,000 classes into the cloud. It took another two weeks of classes for Harvard’s leadership to administer 73,000 Zoom sessions to 600,000 total participants and conclude by the end of that initial period that Harvard could carry along online with no major issues. Save for the students who had to return home to the third of rural America without reliable access to high-speed internet, there were those who even preferred remote higher education.

“Faculty are leaning into the technology rather than simply living with it,” one dean said of the digital rollout. Many students praised the ability to be “up close” with their professors online rather than at the back row of a huge lecture hall, a screen-based intimacy bolstered by opportunities to use the video room chat function to ask questions and discuss materials that made the learning environment more immediate. An associate in the dean of students office added that they were able to fully support a student’s ancillary needs remotely, offering virtual meetings and student check-ins as part of their suite of services to maintain “very much a sense of what the Harvard residential system does.”

Something must be missing, I thought, an ineffable quality of the Harvard experience lost in the transmission through laptop screens and digital cameras. The school’s graduate students about to enter the job market feared economic insecurity caused by the loss of “social capital that you’re able to make while here at Harvard. The connections that you’re able to make,” as one student said. Other students brought a class-action lawsuit against the school to recoup fees and a chunk of their tuition.

The university’s leadership, however, didn’t see the need to offer up any tuition reimbursements. It was the belief of administrators, it seemed, that a Harvard education is above all else that communion of minds between leading professors in their fields and the eager, open minds of their students—a transaction freed of social distractions and distilled to its Socratic essence in the digitized classroom. Or something like that.

For Harvard and other elite schools the transition to remote learning this spring was aided, in part, by their longstanding participation in the development of the MOOC system. The rather unfortunate acronym stands for Massive Online Open Courses, a catchall term for the free and paid classes taught online by professors and researchers, often with some formal affiliation of a home university, and provided through a handful of leading MOOC software platforms. Since 2012, their breakout year, MOOCs have been heralded at different times as the end of brick-and-mortar campuses and the future of higher education, a false prophesy that has allowed them to develop organically into a formative technology system that today boasts of 13,000 classes produced by hundreds of universities and which now appears, in the era of the pandemic, poised to make good on their initial promise.

The MOOC origin story goes back to 2011, when a pair of Stanford professors spun out their first forays into teaching online classes to form Udacity and Coursera, now two of the major MOOC platforms. Soon after, Harvard and MIT formed EdX, their own joint venture. By the end of 2012 some $68 million in investment funding had flowed across what continues to be the big three platforms, and tens of millions more has been invested since. Classes can be expensive to produce well, with a university-quality, semester-length course running anywhere from $25,000 to $100,000.

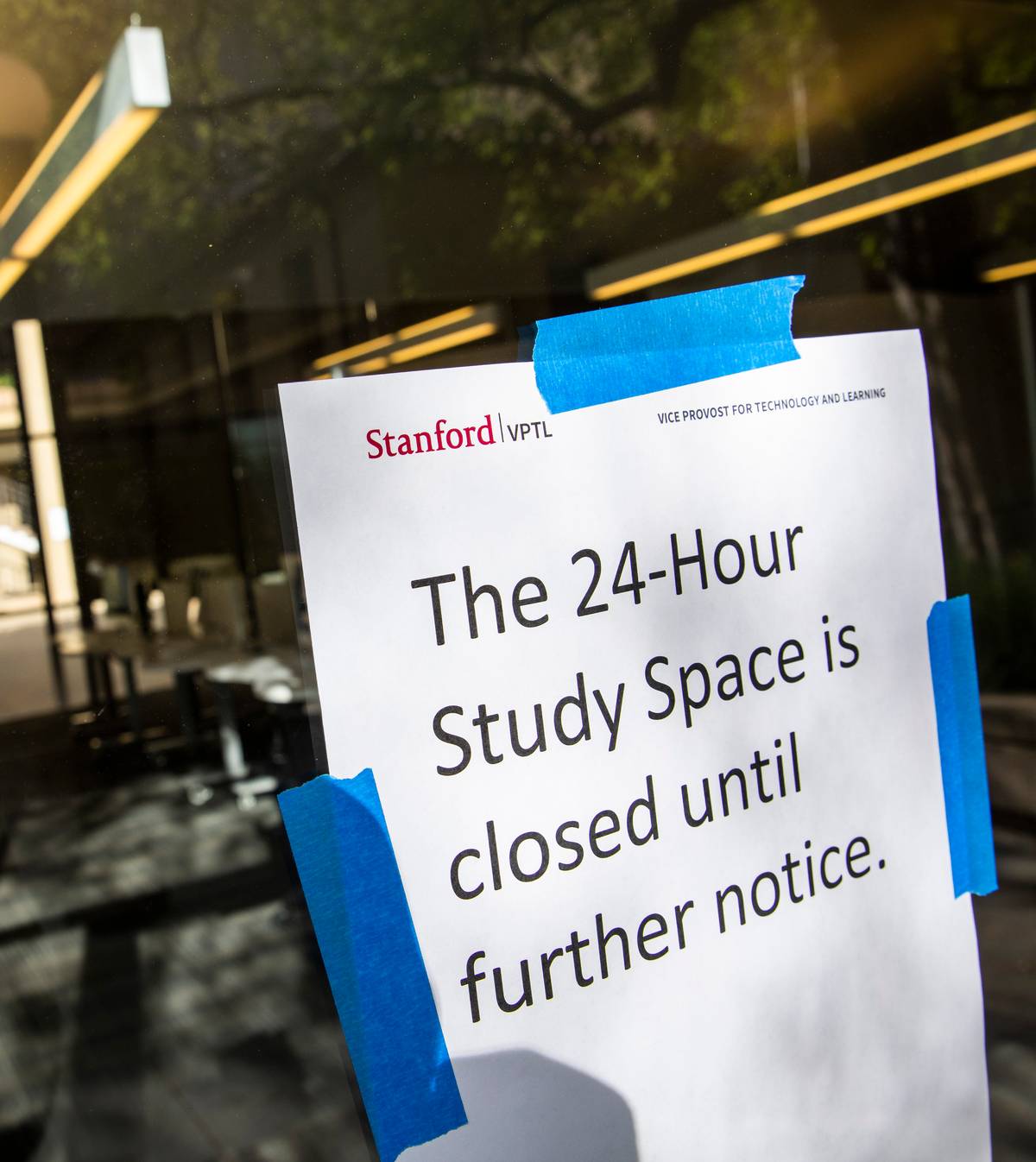

Mixing slick video production with graphics, online text, and curriculums tailored to leverage the virtual classroom, premium MOOCs are the platonic ideal of the low-fi, Zoom-based classroom experience that was the default remote teaching tool over the spring semester. For many schools that have resisted online education, elevating that lo-fi Zoom experience to something closer to the more rigorous MOOCs will be a choice forced upon them by circumstance. In a recent Chronicle of Higher Education survey, 16% of colleges have committed to some form of online teaching this fall because of the threat posed by a resurgent pandemic. Stanford has already declared they’ll teach the entire semester virtually, as has the Cal State system with their 480,000 students.

Masterpieces of World Literature, taught by prominent comp-lit Harvard professors David Damrosch and Martin Puchner, is one of the EdX platform’s more popular liberal arts offerings. The semester-length course runs briskly through 13 sections on “the great texts that have shaped our world,” from Gilgamesh to Candide, up to works by Salman Rushdie and Jhumpa Lahiri. “We believe that literature is the best way to learn about the world because the foundational texts of literature we’ll be discussing are the DNA of entire cultures,” the professors write in their syllabus. Here, it seemed, was my opportunity to not only test out the MOOC classroom but also the potential for an enriching encounter with two of Harvard’s top scholars on the university’s own flagship platform. I signed up.

The potency of this technology was the Harvard branding laid over something digital that had the semblance of college.

The presentation for World Literature is a typical MOOC in that the streaming video is the centerpiece of the course. Two cameras toggle the focus back and forth on the professors seated with coffee mugs at a round, wood table in front of a black backdrop—a stage set perhaps purchased from a PBS fire sale after the cancellation of Charlie Rose. The course section on Borges begins with the professors discussing “The Library of Babel,” one of the author’s great short stories about a world made up of readers who live and die in an infinite library of endless shelves. Taut and coded in myriad allusions, the text brims with opportunities—for not only a close read of Borges’ larger literary project of labyrinths and puzzles, but to explore the connections between his work and the world literatures under this course’s purview.

“It’s sort of as though Borges was a love child of Leibniz and Kafka somehow,” professor Damrosch says to his colleague. “In this strange castlelike world, you know.”

“He grew up in a very literary world. He spoke English with his father. His mother translated—including Kafka, I believe. So Kafka somehow was part of his literary upbringing,” professor Puchner says.

While the professors chat, images of Borges splash across the screen with Ken Burns-style fadeouts. Yet, there was no reading or discussion of the specific contents of the story. Rather, the professors glossed over the text with cocktail party chatter.

“He himself, of course, worked as a librarian on and off for a long time, so he knew this world of libraries,” Puchner says, before dropping into a near-parody of an English professor. “There are changing speculations about the world. There are debates about it. Different schools of thought emerge.”

What was I watching? I suspected that this “Library of Babel” section was light on close readings, and held out optimism for the course’s section titled “On First Reading Borges.” Maybe the analysis would explore the literary puzzles that present an encounter with the Argentine’s work. For the section, Puchner brought in Mariano Siskind, a Harvard Romance language professor. The black background was swapped out for a green-screen image of the Great Hall from the Thomas Jefferson Building of the Library of Congress. On the table were two water glasses with the Harvard crimson shield.

But discussion of the reading did not come. Rather, Siskind, with much excitement, took the title of the section quite literally.

“I was assigned the role of playing Borges. So I borrowed a cane and a jacket, and I played the blind, wise, old man in my high school classroom,” he says, explaining the instance when he first read Borges as a high schooler, for a class assignment with “a skit to convey our interpretation of the short story.” Puchner grins through his colleague’s reminiscence. By the end of this section about reading, no words of Borges have been discussed.

I clicked off to another section of the course, and saw that EdX is offering an opportunity to document the achievement of all this learning. For the price of $149, I could upgrade to the premium account and receive a “verified certificate” for the completion of Masterpieces of World Literature, a token of my Harvard education.

It struck me afterward that the quality of the digital Harvard education, or lack thereof, wasn’t the point. Rather, what I was looking at, the potency of this technology, was the Harvard branding, laid over something digital that had the semblance of college. Most significantly of all, it offered its users—that cheap, catchall term that turns students into a corporate customer base—formal credentials. Though courses like this, branded by Harvard and other elite institutions, have been administered across the MOOC system for years, their potential strength will grow exponentially as the traditional higher education system moves closer to its inevitable breaking point under the pressures of the pandemic.

Prior to the COVID-19 outbreak, colleges across the country had long been suffering from the intense competition to capture tuition dollars from students who continue to prefer dense urban areas they’ll likely live and work and party in after graduation. Over the past three decades, tuition rates have doubled at private schools and tripled at state schools. Meanwhile, the actual return for entry-level work with college degrees has been steadily declining, from $52,000 in 2000 to $46,000 in 2014.

To try to justify their ticket price, small liberal arts schools in rural outposts, and even many midsize institutions, have heavily financed their assets to build out gyms, dorms, tech-heavy student centers, and dumped huge sums into sports programs and training facilities in the hope of recouping their investments through resurgent tuition prices. But the money rarely flows back in. Last year, before any school shut down its campus, analysts had predicted that as many as 15 private and nonprofit colleges would be going out of business annually, a five-fold increase from 2014. In March, as the pandemic surged, Moody’s downgraded their credit rating on the higher education sector from “stable” to “negative.”

It remains to be seen just how catastrophic the pandemic will be for American higher education—it’s something like a natural disaster happening in slow motion, an earthquake still rumbling. But the pandemic has effectively eviscerated the operating budgets of schools across the board, which are being forced to refund room and board, and even grant partial refunds for tuition. Colleges are taking big hits on the canceled events, sports seasons, and any other revenue-generating activity that would have taken place on their now-abandoned campuses. Future revenues once considered guaranteed income are evaporating as well, with more students taking gap years rather than contemplate spending another semester or two paying full tuition for remote learning.

In an April letter to Education Secretary Betsy DeVos, the American Council on Education said the $14 billion aid package for higher education was a fraction of the $50 billion they needed to stave off the “existential threat” of the pandemic. In recent weeks, the earth still shaking, assessments on the initial damage have trickled in. The Labor Department’s report in May found that colleges had 19,200 fewer employees in March compared to the month prior. The University of Arizona furloughed 15,000 employees. Ohio University laid off 140 staffers and professors. Montclair State laid off 20 faculty members. Missouri Western cut 51 faculty, more than a third of those tenured positions.

Ivies and elite schools are responding similarly. Princeton, Stanford, and Dartmouth have frozen new hires.

Meanwhile, students continue to launch lawsuits and some 200 petitions for tuition refunds from schools they deem in breach of contract to provide an education commensurate with annual price tags over $70,000. With revenues at all-time lows, students in revolt over pricing, massive sectorwide layoffs, and government aid packages falling far short of what college leaders say they need to prevent widespread dissolution, a crackup seems inevitable.

One can look to the corporate world during the 2008 recession to get a sense of what lies ahead for U.S. higher education. Back then, with the stock market in free-fall, opportunistic companies with the resources to do so began acquiring competitors at closeout pricing. During the recession’s three-year period, there were some 165 mergers and acquisitions across industries. Distressed financial institutions, once worth around $500 billion, were gobbled up by bigger fish at an 80% discount to their former value.

The equivalent outcome for higher education is that universities with big endowments will extend their footprint and absorb failed colleges in their region, just as Boston College did last month with the downward-spiraling Pine Manor campus. But these satellite campuses won’t really be expansions of the same college education. Rather, they’ll become brand extensions of university headquarters—outposts that provide administrative support and recruiting offices to generate sorely needed revenue.

Much of that revenue will have to come from expanding the school’s online offerings. If the 2008 recession was informative of how colleges will use mergers and acquisitions as a survival tactic, the campuses that have embraced a strategic pivot to digital teaching are likewise instructive for life after the pandemic.

After taking over Southern New Hampshire University in 2003, Paul LeBlanc implemented a Silicon Valley-style growth plan focused on analytics, profit margins, and rapid scaling up, which transformed the private brick-and-mortar campus of a few thousand students into an online powerhouse serving 122,000 degree-seekers. There are other institutions that have achieved similar size—Western Governors University counts 100,000 students on its tuition rolls, with plans to eventually service a million students.

To reach these kinds of numbers, LeBlanc and others have revamped notions of the function of college in a competitive, global corporate marketplace. Not simply offering degrees to U.S.-based students, the university positioned itself as a career accelerator for anyone in the world seeking a first or second degree granted by an American college. With an emphasis on “customer service” and an army of case managers to coach students through the process, the $10,000-a-year tuition, flexible schedule, and shortened academic semesters have allowed SNHU to appeal to anyone with internet access, from active military members to students displaced from their homelands by war or climate disasters. Indeed, after successful forays in Rwanda, the school has announced a plan to serve 50,000 refugees in 22 nations over the next two years.

Along with traditional degrees and a $5,000 continuing-education program, SNHU has begun efforts to join the growing legion of universities broadening their revenue streams and product lines to include micro-credentials—certificates developed in partnership with major corporate conglomerates. It’s this pivot to becoming a clearinghouse for employer-focused skills training that best monetizes the role degree-granting institutions traditionally held for the white-collar workplace—and might prove to be the tactic that saves universities pushed to insolvency by the pandemic.

Stripped of the expensive overhead of English and art history professors exposing students to a spectrum of thought and culture, online education platforms can offer token liberal arts courses while granting certificates and skill-centric credentials to amplify employee productivity. It’s why, like hundreds of other companies, Yahoo sent their employees through a certificate program with Coursera. The steel manufacturer Tenaris uses EdX, the exclusive platform for Harvard’s World Literature course. Last year, EdX struck a deal with Purdue, the seventh such partnership with a major university to offer a graduate degree through its online portal. Along with World Literature, EdX users can browse these degree opportunities within the larger catalog of 2,650 other courses and nearly 300 opportunities for fee-based micro-credentials.

It’s a particular kind of venture-capital mentality that zeroes in on propagating a form of higher education that would reallocate the unprofitable labor of close reading short stories away from school, where students should otherwise be learning skills more useful for the marketplace. It’s the same sensibility I recognized in Harvard’s online course offerings, and when recently returning to the Harvard anniversary book—an almost religious reverence for the sheen of accomplishment and material acquisition, and for the marketplace tactics that made Facebook and Google rich while sinking the creators they monetized for profit.

With the future uncertain for so many colleges, I took some solace in knowing that even students who have to stay at home can still get onto the EdX platform, an ever-growing simulacrum to replace the former college experience. And if they’re willing to fork over a few hundred bucks for the certificate, they can tell everyone they went to Harvard.

Sean Patrick Cooper is a journalist who has contributed narrative features and essays to The New Republic, n+1, Bloomberg Businessweek, and elsewhere. His first book, The Shooter at Midnight: Murder, Corruption, and a Farming Town Divided will be published in April 2024 by Penguin.