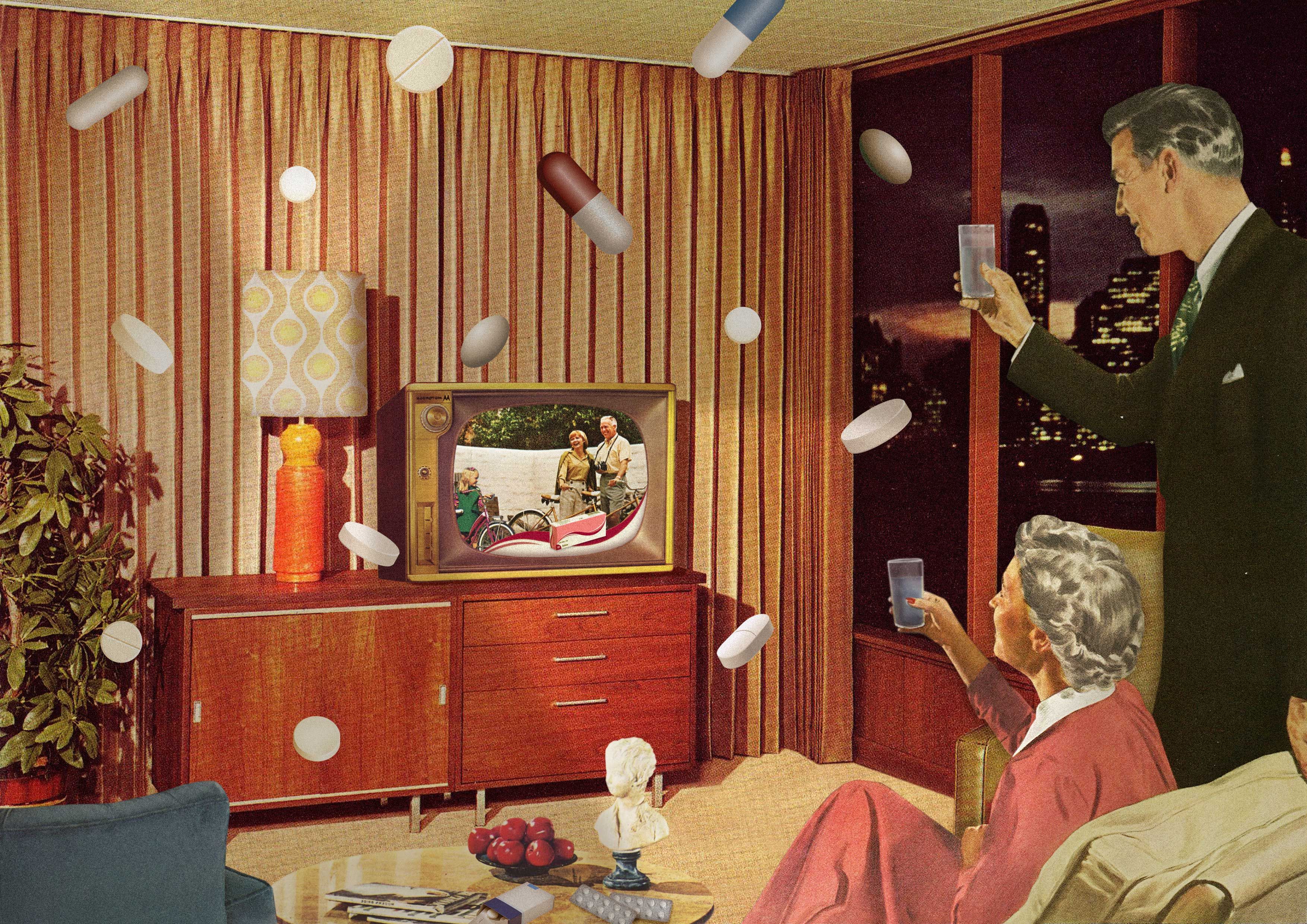

Med Men

How Big Pharma’s investment in the advertising model taught us to view health as another consumer choice

In 2009, I took a job as a copywriter with an ad agency in Minneapolis. After 10 years of academia and publishing in obscure literary magazines, I began writing copy for health care and medical device accounts. The work was boring but the salary was grand, and so I threw myself into learning about stents and dilatation balloons.

About a year into the job a large meeting was called. Suddenly my colleagues—those of the running shoe and vodka accounts—wanted in. Our flagship health care client was looking for a multimedia retail campaign for their pacemaker.

A pacemaker is a simple device that can be lifesaving, essentially a low-voltage clock used to speed up and regulate a slow or sloppy heart rate. It was developed in the late 1950s and patented in 1962. Since then, the technology has not changed much. The device got smaller and the surgery to insert it more streamlined, but as a mechanical object, the design was pretty perfect.

The problem for an ad agency is that there was nothing new to sell. So our strategy team came up with a new approach: chronotropic incompetence.

In younger people, chronotropic incompetence was defined as the inability to increase the heart rate adequately during exercise to match cardiac output. But that clinical condition, while a problem for younger people, was also understood as the normal baseline as people aged into their 70s and their heart rate became gradually less responsive to exertion.

But why should the elderly live with slower heart rates and ragged breathing? This was our clients’ epiphany—what we called a “shared belief.” There was nothing specific in the literature that said chronotropic incompetence couldn’t include the old. Pacemakers for every senior! We would establish this as the standard of care.

By 2010, people 65 and over made up 13.1% of the American population. But the surge in that demographic was clear and imminent. Just 10 years later, they were nearly 17% of the population and by 2030, it’s estimated they’ll be more than 20%. This campaign was worth billions to our client over 20 years.

What I was witnessing more than a decade ago was the new face of health care in America: an alliance between big pharmaceutical companies and marketing firms that replaced the old injunction to “do no harm” with a profit-driven mandate to leave no facet of life unmedicalized. American pharmaceuticals were spending $3.6 billion on direct-to-consumer ads in 2012; as of 2021 that number was at $6.8 billion. In 2021, the total spend for health care advertising in the U.S. was $32.76 billion, with projections that it will rise another 5.2% even over pandemic highs by 2029.

These multi-million-dollar campaigns have been a huge success. In the years leading up to the COVID-19 pandemic, I suddenly knew multiple people who were getting elective gastric bypass and dozens undergoing plastic surgery. Four older ladies I knew swore if they hadn’t had their eyelids lifted and tightened around age 60, they wouldn’t have been able to see. The husbands and children of several colleagues initiated surgical gender reassignment; others invested in bionic prosthetics to fix faulty joints and enhance athletic performance. Nearly everyone in my urban circle had multiple prescriptions for mood enhancing or stabilizing drugs. The vast majority took an SSRI (like Zoloft). Roughly half carried a bottle of something for anxiety—usually Valium or Klonopin—in their purse. A few years ago there was a wave of ADHD diagnoses among my over-40 female friends, who immediately started taking daily Adderall.

This is the new normal: fully medicalized living in America. But back in 2009, it wasn’t yet so. There were huge swathes of untapped audience for voluntary health care. After learning of the potential profits that pacemaker sales promised in a rapidly aging U.S. population, my agency set up a war room and plotted out a multimedia direct-to-consumer (DTC) campaign. Artful black-and-white photos of 70-year-olds finishing half-marathons, doing yoga on the beach, and chasing after their grandchildren. For the superelderly, our campaign showed them walking to get their own mail, climbing stairs, or strolling hand-in-hand.

You’re the evidence, read our headline. (I did not write it.) The message was that we didn’t need fancy scientific studies to prove that pacemakers could help mitigate the symptoms of aging. Older people enjoying their lives and breathing deeply were enough to make the case.

If the activities you love are harder to do, ask your doctor about chronotropic incompetence, advised our copy.

It was easy to believe we were doing something noble: giving elderly people a better quality of life. What we were actually doing was creating a disease state and packaging it for the general public. But weeks before we released the campaign into the world, Katy Butler (whom I knew briefly in my academic life) wrote a gonzo essay for The New York Times called “What Broke My Father’s Heart.”

After a disabling stroke at age 79, Butler’s father suffered an inguinal hernia that surgeons refused to repair unless he was fitted with a pacemaker. What followed was five years of increasing dementia, memory loss, strokes, falls, blindness and incontinence, through which his heart kept beating. When his wife of 60 years asked doctors to deactivate the pacemaker and let her husband die peacefully, they refused.

Butler’s father suffered for five days with end-stage pneumonia, gasping for air through wet lungs, until lack of oxygen finally overcame the pacemaker’s pull. A year later, Butler’s mother rejected a recommended bypass surgery, had two heart attacks in quick succession, and joined her husband in death.

The article—which led to Butler’s New York Times bestselling book, Knocking on Heaven’s Door—was circulated somberly by one of our clients at the medical device company, who then put the consumer campaign on hold. We never did resume. But somehow the message we had intended for the public got out to doctors, who began recommending pacemakers more widely. My own parents both received pacemakers recently, in their 80s, despite a long list of health problems that keep them bound to the couch. When I asked why, neither could say.

It was easy to believe we were doing something noble: giving elderly people a better quality of life. What we were actually doing was creating a disease state and packaging it for the general public.

My brush with DTC medical marketing happened at a time when advertising itself was changing course.

After years of wooing consumers with commercials and billboards, marketers realized it was easier—and more profitable—to keep customers than to court them. Mobile technology made direct communication with buyers possible. The agency I worked for acquired a massive loyalty/one-to-one enterprise in mid-2010 and began turning campaigns that way.

Loyalty marketing is behind the explosion in subscription services and rewards programs—for car rentals and hotels, groceries and gas, makeup purchases, coffee orders. If a customer felt like they were “part of” the brand, and like they were getting a special deal in exchange for their membership, they would keep coming back.

Direct-to-consumer marketing of medical devices never really caught on among the B2C (business to consumer) audience. But it’s used broadly by physicians and hospital administrators (B2B). Device manufacturers stage or rent booths at conferences, where they engage [pay] key opinion leaders (KOLs)—star doctors in their fields—to speak and recommend their products; the manufacturers also treat potential buyers to lavish dinners, swag bags, and bulk pricing that make procedures more profitable over time.

But pharmaceutical companies embraced DTC subscription marketing, blanketing nearly every inch of television ad space, but especially those programs watched by older Americans—news and talk shows, primetime dramas, Jeopardy!, and reruns of Blue Bloods. Most of these ads use the strategy my team was given—popularizing a worrisome new disease state with a memorable name—to convince people they’re in need of help.

One of the earliest examples is Fosamax, a drug developed by Merck to treat osteoporosis and released in 1995. When sales of Fosamax disappointed the company, they hired a consultant who came up with an outrageous—and wildly successful—marketing plan. First, he set up a nonprofit called the Bone Measurement Institute. The nonprofit funded low-cost bone density scanners that tested only a wrist or a heel, and made sure they were placed in doctor’s offices nationwide.

Most important, their scanner’s chart spit out three categories for bone density: Good bone health was green, osteoporosis was red. But in the middle was a new category that showed mostly normal bone thinning, due to age or slightness of frame. They called it osteopenia, a term coined by doctors a few years earlier. Merck used this term, however, to scare women into taking medications, thereby medicalizing and monetizing the natural effects of aging. If people had once believed that losing bone density was just part of getting older, the ad-men of the pharmaceutical industry were here to sell a new dream—that every ailment, including mortality itself, could be treated with the right product.

At the same time, Merck lobbied Medicare and private insurance companies to cover bone scans and formulated a low-dose version of Fosamax for osteopenia. A 1997 FDA “clarification” on how broadcasters could get around the required drug risk statement (for instance, by providing an 800 number for viewers to call for information) opened the floodgates. In the following years, marquee actresses like Sally Field and Blythe Danner promoted osteopenia drugs on TV. Millions of women were converted overnight to a condition they’d never heard of—that their doctor might have learned about at a conference the year before. Fosamax went from just over $500 million in sales that year to $3.2 billion in 2005, becoming Merck’s second-best-selling drug.

Problems emerged in the mid-2000s, when it became clear Fosamax actually caused an increased risk of bone fracture in some women, especially of the legs and jawbones. Patients who were taking the drug were warned not to have dental surgery due to the risk of infection and possible loss of their jaw. By 2006, the American Association of Endodontists drew a definitive link between Fosamax and “jaw bone death,” issuing a position statement that warned against root canal in women taking the drug.

Even for the women who didn’t suffer side effects, the drug just wasn’t terribly effective. A systematic review of 33 studies published by Therapeutics Initiative in 2012 found “no statistically significant reduction in hip or wrist fracture” for women who fell into the mild bone loss or “osteopenia” category. It was a slickly produced mirage.

“Sickness used to happen to you,” says Kim Witczak, founder of the nonprofit Woody Matters, which advocates for pharmaceutical drug safety. “Now we live in a world where it’s being sold to us.”

We’re told repeatedly how expensive it is to bring new drugs to market, and this fact is used to justify the methods Pharma uses to push its products, from television advertising to free samples in doctor’s offices. They need to generate income in order to create the next blockbuster cure. But Witczak says this is a convenient myth.

“Pharma companies spend $480 billion every year,” she says. “Of that, 5% goes to research and development; the other 95% is spent on marketing. There is a lot of self-interest working behind the scenes to come up with brand new disorders and dysfunctions, medicalizing everyday life, portraying mild problems as serious by widening diagnostic boundaries, creating extensive assessment tools, and corrupting medical research.”

Kim Witczak knows this corruption, because she’s lived it.

In 2003, her husband, Woody, was prescribed Zoloft off-label for sleep issues related to an exciting but stressful new job. He was given a free, three-week starter pack of the drug by his general practitioner—a pack that doubled the dose of the drug automatically after one week.

Kim returned from an overseas business trip to find her usually cheery husband ranting, sweating, and telling her it felt like his head was “floating outside [his] body.” She calmed him down and they called the doctor who insisted the Zoloft needed a few more weeks to kick in. Woody should stay on the doubled dose of the drug.

Things seemed to level out. Kim and Woody were planning a 10th anniversary trip, to Thailand. She felt confident enough to go out of town on business again. But when a day went by and she couldn’t get hold of Woody—then his business partner called to say he hadn’t showed up for a meeting—she got nervous. She called her dad and asked him to check the house.

Kim Witczak’s father found her husband, Woody, age 37, hanging dead from the rafters in their garage. At first, stunned, she had no idea why her happy, successful husband had taken his own life, abruptly, midcalendar, without even leaving a note. Then her brother-in-law pointed out that investigators on the scene seized the bottle of Zoloft. So she started asking questions.

She would spend the years after burying her husband pursuing a lawsuit against Pfizer, the maker of Zoloft; speaking to the Food and Drug Administration about DTC advertising of pharmaceuticals; and pushing for a “black-box” warning (BBW)—the most severe warning the FDA issues, that a medication has potentially life-threatening side effects—on antidepressants.

Witczak settled her wrongful death suit against Pfizer in 2006, for an undisclosed amount—and with no NDA, so she could keep telling her story. Pfizer documents unearthed by her lawyers during the court case showed Woody precisely fit the suicidality profile from clinical trials: a man in his 30s whose dose was abruptly doubled. But doctors who were gifted boxes full of starter packs by sales reps were never warned.

Sickness used to happen to you. Now we live in a world where it’s being sold to us.

Multiple factors brought us to where we are with consumer health in America. There’s the aging of baby boomers—that generation determined to stay youthful through science, remain in power forever, and never die. But the love of medical intervention seemed to stretch down through the generations. A recent study shows that most millennials take at least one prescription medication each day.

There was the shift in sales strategy, leveraging technology to reach customers directly, preying on their pain points and worries, using their demographic information and internet search histories to target exactly what pill, product or procedure they are most likely to believe they need. Meanwhile pharmaceutical companies took a near universal turn toward advertising new disease states—osteopenia, premenstrual dysphoric disorder, social anxiety disorder, binge eating disorder, low T—in order to expand the market for their drugs.

Yet the cleverest, most efficient method to sell new drugs requires no fancy advertising or media buys. It’s the simple chart, graph or questionnaire at your family doctor’s office.

Merck highlighted the osteopenia results of patients’ bone density scans in a bright warning yellow. The Sackler family, makers of Oxycontin, created the 1-10 pain scale with simple sad, mad, and happy faces to generate conversations between patients and their doctors about the need for painkillers. And that questionnaire you fill out at every doctor visit—asking if you’ve felt worthless in the past two weeks, had trouble concentrating, if you’ve eaten too much or too little—was written by three doctors funded by a grant from Pfizer, a brand that’s now as embedded in the zeitgeist as Coca-Cola, even featured in Facebook posts and tattoos.

“That questionnaire is nothing more than a sales funnel,” says Witczak. “It gets people to focus on these problems—even if it’s not what they came in for—and gives doctors the perfect opening to have a conversation, and once they come up with the disorder to match the symptoms, they’re in the funnel. They’re Pharma’s customer. Often, for life.”

When she started Woody Matters, Witczak’s original fight was with Pfizer, maker of Zoloft. But in 2020 with the start of the pandemic, her mission broadened. Pfizer is also the manufacturer of COVID vaccines and the antiviral therapy Paxlovid—both endorsed and purchased by the U.S. government in large quantities. For years, Witczak had questioned Pfizer’s methods and their transparency about clinical trials, but when she asked her standard questions about the Pfizer vaccines, her friends and admirers—people who had attended her fundraisers and cheered her investigative work—insisted she’d gone too far.

“I was told that while they respected my other drug safety advocacy, I was completely wrong in the way I was looking at the vaccines,” she says. The resistance came mostly from former business colleagues, the liberal urban professionals who had kept her nonprofit afloat.

As she voiced skepticism about the COVID-19 vaccines, support for Woody Matters ground to a halt.

Pharma companies spend $480 billion every year. Of that, 5% goes to research and development; the other 95% is spent on marketing.

There’s a case to be made that more and better access to health care options—including drugs—improves the lot of most people. Take telehealth, which became the standard of care during the pandemic. For the first time, people didn’t need to take hours off work and sit in a crowded, germy waiting room to be seen for a skin lesion or a prescription refill. This has led to hybrid health/lifestyle sites like forhims.com (and forhers.com), where online patients can get help with depression, sexual dysfunction and hair loss—all with a single video conference.

In 2022, tech entrepreneur Mark Cuban launched Cost Plus Drug Co.—a for-profit online pharmacy that sells generic versions of commonly prescribed drugs for the cost of manufacturing them plus a 15% markup. Cuban is undercutting the prices charged by Pharma companies and providing people with a sustainable, affordable way to treat literally hundreds of conditions from allergies and acid reflux to diabetes, thyroid disease, multiple sclerosis, heart failure and cancer.

In a perfect world, low-impact options like virtual mental health counseling, preventive medicine, affordable prescription drugs, and integrated health systems would sound like improvements in terms of customer choice.

That equation is already complicated enough for adults whose choices are shaped by Pharma’s massive ad campaigns and influence on medical professionals, but today it may be children who represent Pharma’s ripest opportunity for profit. Caught between pediatricians, schools, drug companies, governments and parents, kids are—from a sales perspective—the ideal consumers because they aren’t required to give their consent to be administered drugs.

In addition to the schedule of 20-25 individual vaccines by 15 months (mandated in varying formulas by states and school districts), the market for drugs that control kids’ behavior is exploding. From ADHD to anxiety to bed-wetting, there’s a pill to treat them—endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), whose principal donors include Abbott, Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Novavax, and several formula makers. Criteria for childhood disorders keep broadening. For example, in 2003, just 5.4% of school children were diagnosed with clinical anxiety. The figure grew to 8% in 2007 and 8.4% by 2011–12. In 2016-19, 9.4% of children were diagnosed with anxiety serious enough to require treatment.

In January 2023, the AAP issued guidelines recommending that doctors begin treating children with obesity using newly approved pharmaceuticals and bariatric surgery (gastric bypass), as early as age 12. (Handily, childhood obesity surged during school closures and lockdowns imposed by elected officials in response to COVID-19.) And since 2021, the AAP in partnership with state and federal government policy, has supported highly medicalized “gender-affirming care” for the fast-growing number of trans youth, beginning with puberty blockers. This leads to the use of feminizing or masculinizing hormone therapy and in some cases genital surgeries, which require drug therapy for life.

Combine that with the ever-growing list of vaccines that are required for both children and adults—to attend school or work, and at one point in 2022 even enter a restaurant—and it’s clear that Pharma has become an unavoidable third rail of American life.

Like that infamous Batman scene where the walls are closing in as the ceiling descends, relentless health care marketing combined with new government mandates and agency guidelines threaten to squash the consumer—resulting in a system that is less about the individual and more about an inescapable system of medical processes and rules.

But it should come as no surprise. We saw a hint of this new world back in 2010, when Katy Butler wrote her family’s story. Her father was required to get a pacemaker implanted, ostensibly to help him survive surgery. But when he was dying in fear and misery, unable to take a breath but stuck in life as the device sent electrical pulses to his heart, the medical powers from on high refused to turn it off.

Ann Bauer is the author of four books, including the novels A Wild Ride Up the Cupboards and The Forever Marriage. Her essays have been published in The New York Times, ELLE, Salon, Slate and The Sun. Follow her on Twitter @annbauerwriter.