Holocaust Agitprop in Berlin

A film of nude people playing in a gas chamber is but one piece aiming to shock at the Berlin Biennale art show

Berlin construction workers are accustomed to excavating the occasional unexploded Soviet shell, but in 2010, while digging a subway tunnel, a crew unearthed a rather different war relic: a cache of 11 sculptures preserved beneath Berlin City Hall. Experts quickly determined that the items, which included the work of long-forgotten Jewish-German modernists like Naom Slutzky and Otto Freundlich, were part of a collection of “degenerate art” confiscated during the Nazi period and, in 1937, deployed throughout the Reich to demonstrate the “Judeo-Bolshevik” domination of German culture.

Seventy-five years after the Nazi campaign against Weimar modernism, the German government is underwriting 26-year-old Polish artist Lukasz Surowiec’s campaign to plant his anti-fascist art in Berlin’s soil. As part of the seventh annual Berlin Biennale, which opened last week and runs through June, Surowiec is transplanting hundreds of birch trees uprooted from the forests surrounding the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp to various spots around the German capital in an effort to “deepen the memory of the Holocaust.” But while Surowiec’s tree installation is designed to draw further attention to the Nazi genocide, his piece is the Biennale’s token: It provides a semblance of contemplation in an exhibit concerned with hackneyed sensationalism and heavy-handed agitprop.

Germany is currently experiencing a profound, if subtle, shift in its dealings with the past—look no further than Günter Grass’ cloddish cri de coeur against Israel, “What Must Be Said,” which provoked an impassioned debate about the limits of national guilt. This fissure—the debate of how Germany’s past affects the discussion of contemporary politics—is starkly on display in this year’s Biennale. Partially underwritten with a $3 million government grant, this year’s show is an exposition of hyper-political art addressing recent German history, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the Occupy Wall Street movement; interesting subjects in more capable hands.

It was not long ago that Germans were reliably, almost professionally, contrite about their fascist past, establishing a strong relationship with the state of Israel and regularly commemorating the Holocaust. Indeed, while the academic world was critically savaging Daniel Jonah Goldhagen’s 1996 book Hitler’s Willing Executioners, which argued that Germans were in thrall to a particularly “eliminationist” strand of anti-Semitism, Germany feted him. The late Israeli journalist Amos Elon observed that Goldhagen, who insisted on calling perpetrators of the Holocaust “Germans” rather than Nazis, was greeted as “a pop star or visiting statesman.”

Though the reticence to criticize Israel largely remains in German society, the Berlin Biennale is aggressively flouting these taboos, and the country’s media isn’t paying much attention. Curated by the Polish artist and controversialist Artur Zmijewski, whose previous work includes a video in which he pressures a reticent Holocaust survivor to re-tattoo the fading concentration camp number his arm, the collection of agitprop art offers a rather singular view of the Israeli-Arab conflict.

“Key of Return,” a Claes Oldenburg-like sculpture of a giant key, advocates for the “right of return” of Palestinian refugees, which would likely result in the demographic destruction of the Jewish state. At first blush, its inclusion appears to be balanced by work of Yael Bartana, an Israeli video artist whose “First International Congress of the Jewish Renaissance Movement” advocates, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, a return of Jews to their ancestral homes in Poland. But as one Polish critic noted, the “parallels between the Zionist movement and the invasion [sic] of Palestine in 1947 are intentional” in Bartana’s work. If her politics were still opaque, Bartana is holding a symposium at the Biennale posing the leading question: “How should Israel change to become part of the Middle East?”

Or how about the contribution of Palestinian artist Khaled Jarrar, who created postage stamps for a Palestinian state, which were recently issued as usable postage by the German post office? Jarrar also offers Biennale visitors a chance to get their passports stamped with stamps from Palestine, whose image conspicuously erases Israel from the map. Unsurprisingly, Jarrar advocates a one-state solution, something which, in years past, might have unnerved German government sponsors.

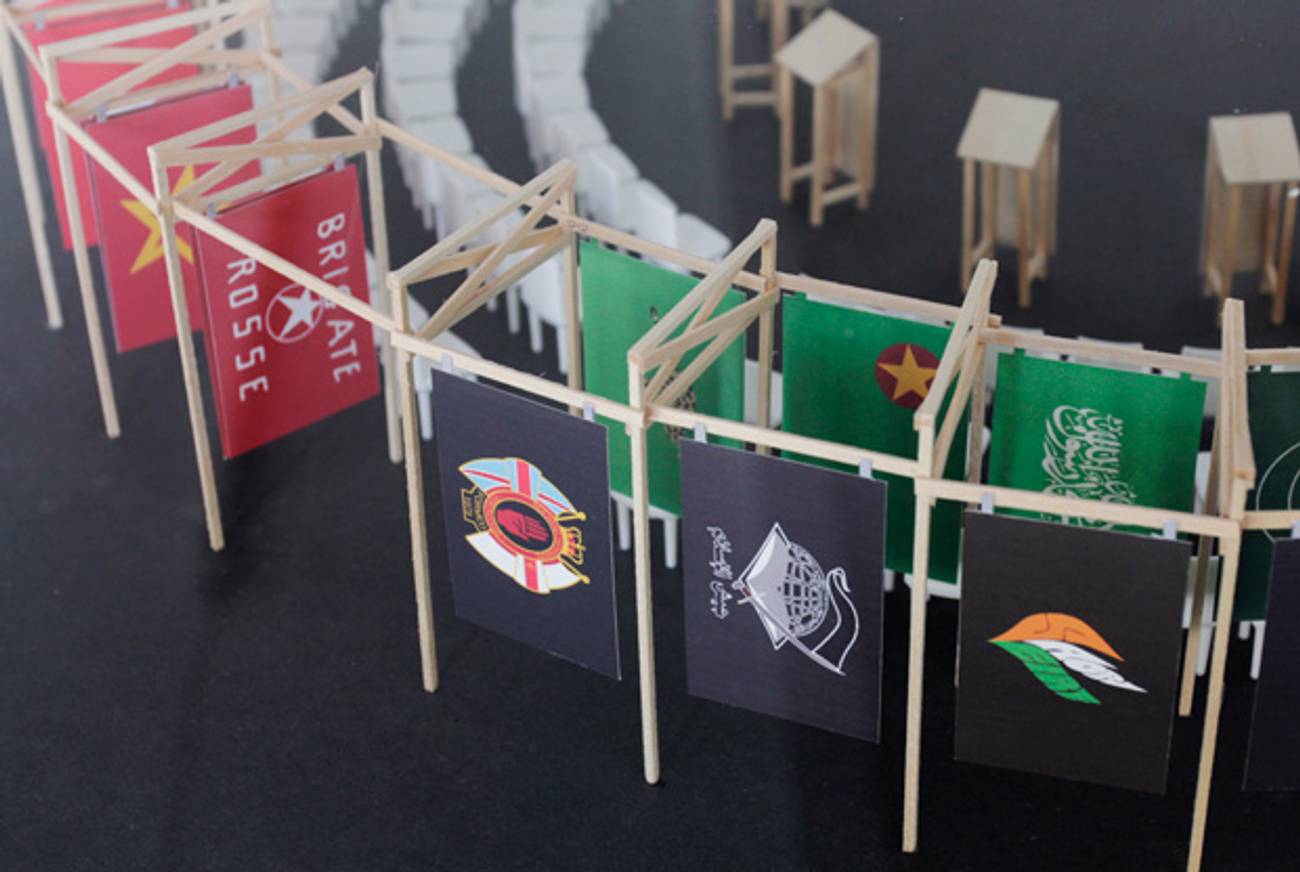

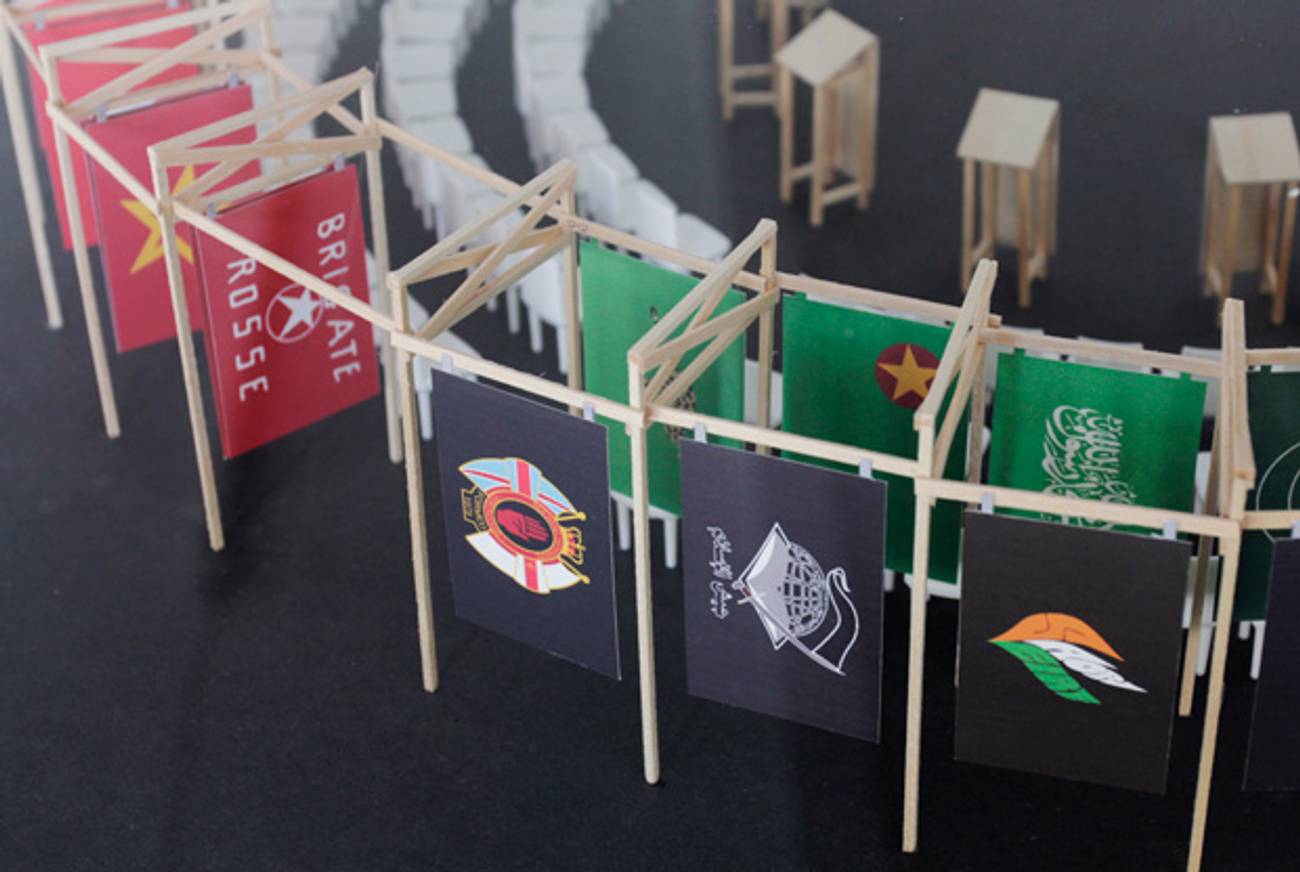

“The New World Summit” by Dutch artist Jonas Staal is less a work of art than a debating forum for extremist groups. Staal is staging a two-day conference and “alternative parliament” at the Biennale, composed of the “political and juridical representatives” of outlawed terrorist organizations who will, say the organizers, present their visions of democracy. According to Staal, Western “political prejudices, diplomatic relations, and economic or military interests play a decisive role in labeling an organization as a ‘terrorist group’ ” and make it difficult for groups like al-Qaeda, Hamas, and Hezbollah to “perform their activities.” This, Stall says, demonstrates the hypocrisy of Western democracies.

In a clumsy manifesto co-signed by Biennale curator Zmijewski, Staal declares that the methods of Islamist groups and the United States are fundamentally “two sides of the same coin”—the “violent policy of the so-called ‘terrorists’ therefor [sic] reflects the violent policy of the so-called ‘democracies.’ ” Staal’s naive project “to include those who are excluded” allows for fanatical anti-Semites and various religious extremists to present their case on German soil (the entire list of proposed “parliamentarians” can be viewed here).

But the most controversial work of the show is “Berek,” a short film Zmijewski made in 1999 that features a group of smiling, naked people playing a game of tag in a Nazi gas chamber. Last year “Berek” was withdrawn from Berlin’s prestigious Martin-Gropius Bau exhibition hall after complaints from Jewish groups, setting off a series of furious counter-complaints of censorship. (The newspaper Die Tageszeitung protested that the film was removed “without debate.”)

According to Zmijewski, the film shines a spotlight on the oppressive nature of memory: “The murdered people are victims—but we, the living, are also victims. And as such we need a kind of treatment or therapy, so we can create a symbolic alternative; instead of dead bodies we can see laughter and life.” A Polish art critic quoted on the Biennale website argues that “Berek” offers “a way of breaking with the kitsch of the Holocaust.”

How this expands our understanding or interpretation of genocide is anyone’s guess, but trite and pretentious artistic “representations” of the Holocaust are depressingly common. The 1998 exhibit “Mirroring Evil” at the Jewish Museum of New York induced outrage with works like “Prada Deathcamp,” a model of a concentration camp built using a Prada hatbox. The artist, Tom Sachs, told the New York Times that he was, for some inexplicable reason, “using the iconography of the Holocaust to bring attention to fashion.” But for those of a more radical persuasion, Sachs offered a connection between capitalism and fascism: “The death camps are examples of amazing German engineering and design. And there are strong links between military products and consumer products.” According to the Jewish Museum, “LEGO Concentration Camp,” a reconstruction of Auschwitz made from Lego bricks featured in the “Mirroring Evil” exhibit, was included for its observation that “the same type of creative construction that little boys do with Lego also took place at concentration camps.”

Such piffle is often deployed to defend lazy art that exists to “shock” its viewer (and to point this out is to court charges of philistinism). And most participants in the Biennale can similarly offer only dopey platitudes and maundering political manifestos about “redefining politics,” the “undemocratic” nature of declaring Hamas a terrorist organization, and suggestions that we “speak out against injustice.”

If the organizers of the Berlin Biennale are concerned about preserving, extending, rethinking, or contextualizing the memory of the Holocaust—which is done, to employ the cliche, so it never happens again—why not muster the artistic bravery to confront contemporary examples of anti-Semitism? Because they exist. And quite a few of them could probably be found milling about the Biennale’s “New World Summit.”

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Michael Moynihan, Tablet Magazine’s “Righteous Gentile” columnist, is the cultural news editor of Newsweek/The Daily Beast.

Michael Moynihan, Tablet Magazine’s “Righteous Gentile” columnist, is the cultural news editor of Newsweek/The Daily Beast.