Amélie Wen Zhao had what looked like a very promising career as a young adult fiction author ahead of her. Last January it was announced that Zhao, who was born in Paris, raised in Beijing, and currently works in finance in Manhattan, had sold a debut three-book trilogy to Delacorte Press, a Penguin Random House imprint, in “a major deal.” In publishing-speak this means her advance was at least $500,000, an outcome most first-time authors writing in any genre could only dream of.

Zhao’s debut, Blood Heir, was due to be published this June. It’s an adventure “pitched as Anastasia meets Six of Crows,” referencing the popular film and fantasy novel. “In the Cyrilian Empire, Affinites are reviled,” the book’s promotional materials explain. “Their varied abilities to control the world around them are unnatural—dangerous. And Anastacya Mikhailov, the crown princess, might be the most monstrous of them all. Her deadly Affinity to blood is her curse and the reason she has lived her life hidden behind palace walls.” When Ana’s father, the emperor, is killed, she is framed for his death and “must flee the safety of the palace and enter a land that hunts her and her kind.”

Now, only Zhao and a handful of other readers will ever know how Ana’s quest ends, because the book may never reach shelves. Per an announcement Zhao posted to Twitter this week, Blood Heir isn’t being released at all—she has decided not to publish it, and Delacorte has agreed. On its face, it’s an astonishing turn of events: only months away from the scheduled publication date, Zhao says that she decided to kill her own book. Authors who win lucrative three-book deals don’t, as a general rule, decide to preemptively unpublish their debut with advance reader copies already circulating.

Zhao’s troubles appeared to have started last week. But it’s impossible to comprehend her precipitous fall without understanding a little bit about the insular, frequently vicious world of “YA Twitter,” an online community composed of authors, editors, agents, reviewers, and readers that appears to skew significantly older than the actual readership for the popular genre of young adult fiction, which is roughly half teens and half adults. As Kat Rosenfield, a Tablet writer who is herself a published YA author, wrote in a deeply entertaining Vulture feature on “The Toxic Drama on YA Twitter,” in the summer of 2017, “Young-adult books are being targeted in intense social media callouts, draggings, and pile-ons—sometimes before anybody’s even read them.”

These paroxysms tend to focus on issues of social justice and representation. And to be sure, many respected authors, publishers, and other YA figures argue that the genre has legitimate work to do with regard to diversity and representation. As is the case in many other areas of media, the competitive nature of YA publishing, and the limited, oftentimes rather winner-take-all nature of its financial rewards, mean that those who enter the field with significant resources already at their disposal often enjoy an unfair advantage. “The latest statistics show that authors of color are still underrepresented, even as books about minority characters are on an uptick,” notes Rosenfield.

But while some of the social justice concerns percolating within YA fiction are legitimate, the explosive manner in which they’re expressed within YA Twitter is another story. Posing as urgent interventions to prevent the circulation of harmful tropes, the pile-ons are often based on selective excerpts pulled out of context from the advance copies of books most in the community haven’t read yet. Often, they feature critics operating on the basis of idiosyncratic ideas about the very purpose and nature of fiction itself, elevating tendentious interpretations of the limited snippets available to pass judgement on books before they have been released. To take one example, a viral blog post that sparked a pile-on against a highly anticipated and eventually well-reviewed book, The Black Witch, “consisted largely of pull quotes featuring the book’s racist characters saying or doing racist things,” as Rosenfield explained. Most adult readers across genres understand that representing a morally repugnant position as part of a broader narrative is not the same as endorsing that opinion, but this is the sort of obvious-to-everyone-else point YA Twitter tends to confuse or outright reject. “I have never seen social interaction this fucked up,” one “author and former diversity advocate,” who, like so many others, insisted on anonymity, told Rosenfield in an email. “And I’ve been in prison.”

Further heightening the drama, these pile-ons are often accompanied by claims that those who have been selected for dragging or excommunication have not only sinned against social justice, but pose a safety threat to others in the community. To be sure, online harassment can be a genuinely scary experience when it occurs. But within YA Twitter, harassment accusations are almost a tic at this point, and many of them don’t pass the smell test. Rosenfield, for example, asked the author of the anti-The-Black-Witch post for an interview, was politely turned down, and then watched as she “announced on Twitter that our interaction had ‘scared’ her, leading to backlash from community members who insisted that the as-yet-unwritten story would endanger her life.”

Between Rosenfield’s article and my general fascination with pathological social rituals in online communities, I had long kept one eye on YA Twitter. Last week, I was tipped off that there seemed to be some sort of drama brewing there—someone or some group had started a whisper campaign against this Zhao person. A YA reviewer with just 800 or so Twitter followers appears to have been the first to make these accusations public. She said: “I have nothing to lose by it and have the time, I’ll tell you which 2019 debut author, according to the whisper network, has been gathering screenshots of people who don’t/didn’t like her book. Amelie Wen Zhao.” As justification for airing whisper-network rumors, the woman tweeting suggested that Zhao’s alleged wanton screencapping constituted an actual threat of some kind: “Readers should be aware of this for their own protection. That’s why I’m saying it publicly after some confidential sources let me know privately.” The tweeter, who is white, explained to a skeptical replier that “I’m not ruining her life. I’m making public with permission what POC told me privately so in order to protect reviewers.” (If a confused friend ever asks you to sum up the culture of YA Twitter in one sentence, “Imagine a white woman explaining that she is spreading unverifiable rumors about a first-time author of color in order to protect people of color” will do nicely.)

I mentioned the whisper campaign on Twitter without naming names, thinking it might fizzle out, and then forgot about it. But by the time I again dipped a toe into YA Twitter a few days later, on Tuesday night, things had exploded: YA Twitter was attacking Zhao’s still unpublished Blood Heir on multiple fronts. As usual, the standards of argument appeared rather strange and lacking, at least to an outsider. L.L. McKinney, a YA author who recently published her own debut novel, highlighted for her 10,000-plus Twitter followers the fact that one of Blood Heir’s blurbs read, in part, “In a world where the princess is the monster, oppression is blind to skin color, and good and evil exists in shades of gray….” “….someone explain this to me. EXPLAIN IT RIGHT THE FUQ NOW,” she tweeted. “I don’t give a good god damn that this is an author of color,” she said later in the tweetstorm. “Internalized racism and anti-blackness is a thing and I…no.” The argument, such as it is, appears to be that because in our world, oppression isn’t blind to skin color, to write about a fantasy world in which it is is an act of “anti-blackness.” (McKinney didn’t respond to a request for comment submitted via her agent.)

But perhaps the most damaging, drawn-out broadside came from Ellen Oh, an established YA writer who is herself of Asian descent, and who co-founded We Need Diverse Books. Oh published an extended tweetstorm to her 11,000-plus Twitter followers in which she noted that “colorblindness is extremely tone deaf.” Then she proceeded to address Zhao without mentioning her by name. “Now I’m going to talk directly to Asian writers,” she wrote, particularly “Asian writers who did not grow up in western countries” like Zhao. “Your lack of awareness may not be your fault given your lack of cultural context, but it IS your fault if you do not educate yourself when it is expressly brought up to you.” The admonishment continued, “And if you have the luxury of getting this important criticism before your book is actually published, it is YOUR responsibility to make it right. Do right by the audience that your book will be reading. Do right by the kids who will be reading your book.”

While the colorblindness accusation was part of the campaign against Zhao, the most potent claims of anti-black racism stemmed from a rumor that swept through the community based on the advance copies of Blood Heir that had already been released. It was alleged that the novel contains scenes involving chattel slavery, or something like it, including one in which a black character named May sings to the protagonist Ana immediately before dying. The assumption that May is black fueled a lot of anger—the criticism seemed to be that Zhao was positioning a black character as disposable, as a plot device.

Others complained about the fact that the book seemed to be about chattel slavery, although, based on the published tweets, no one could explain exactly what it was about Zhao’s treatment of the the subject that was offensive. “[I]t is also HIGHLY troubling that no one in the process of publishing or editing Blood Heir saw a story about slavery, trafficking, and race relations and thought to bring in a sensitivity reader, or even several,” noted one member of the community who didn’t level any specific critiques about the book’s handling of these subjects. “[T]o put something that resembles chattel slavery SO CLOSELY is distasteful,” opined another, the implication being this simply isn’t a subject to be written about. Among other critics, there seemed to be a lack of understanding that “slavery” doesn’t mean “American slavery” and that the concept has a broader context and history than that. “[R]acist ass writers, like Amélie Wen Zhao, who literally take Black narratives and force it into Russia when that shit NEVER happened in history—you’re going to be held accountable,” said one contributor to the pile-on. “Period.” (Parenthetical after the period: Russia has its own recent history of what is certainly one strain of slavery).

The controversy hinges in part on the character May being black. Whatever one thinks of the arguments that the book—or the excerpts of it that have been posted online—is problematic, if May isn’t black, it is a lot harder to justify treating her depiction or treatment in the book as an act of anti-black racism. And there just doesn’t appear to be any hard evidence that Zhao intended for May to read as a black character, to the extent real-world concepts of race even make sense in a fantasy setting (Zhao didn’t respond to a DMed request for comment on this and other aspects of the controversy, or to a request for comment sent to her agent).

In one excerpt from Blood Heir posted online, May is described as having skin “the bronze of their sands at sunset,” their referring to a geographic location in the book. And the woman who appears to have made the whisper campaign public with her initial tweets noted that at another point May is described as “tawny.” Of course, “black” or “African-American” covers a wide range of skin tones, but “tawny” is only questionably one of them. “Bronze” is ambiguous—I’d always associated it with Mediterranean people, and it certainly applies to some people of African descent, but it can have Latin American connotations, too. All in all, if someone is described as having “tawny” or “bronze” skin in a fantasy novel, there’s just no good reason to assume on the basis of that and that alone they’re black in the sense of how that term is used as a racial designator in the real world. May is also described as having eyes that are a “startling aquamarine” color, further chipping away at the case that Zhao intended to code her as our-world black—again, we’re debating whether a fantasy character in a fantasy universe fits already-fuzzy racial categories here in the real world, which on its own suggests something has gone seriously wrong—giving pause to one YA tweeter, who wrote, “first of all why does the black girl have blue eyes[?]” Good question!

I didn’t have access to an advance copy of the book and wanted to make sure I wasn’t missing anything so I emailed Oh, the YA writer whose tweets to Zhao as a fellow author of Asian descent had castigated her for her lack of awareness and cultural context. Oh has read the book, and to her credit, given that we had been arguing about this on Twitter, she sent me a thoughtful and civil response, but one that didn’t really contain any new or compelling evidence Blood Heir can be fairly called a racist book. Oh argued that May was indeed coded black on the basis of a number of bits of evidence about her, ranging from her skin color to the fact that she was indentured and sold. These details about May’s background read to Oh like references to slavery and slave traders and, in her reading, May’s character fell into the “Magical Negro” trope overall. The problem with this line of interpretation, again, is that it insists on viewing every fictional reference to slavery or indentured servitude, or to characters with dark skin, through an American lens, and judging them by that standard. It feels like an act of trope-colonization.

None of these details mattered to YA Twitter, anyway. Soon, many in the community, or those within it tweeting publicly about the controversy, at least, had reached the consensus that Blood Heir was undeniably, obviously racist, that it was a sign of something deeply wrong within YA publishing that it was going to be unleashed on the world, and that Zhao should be held responsible. “Agents, editors, publishers, YOU are the gatekeeper as much as writers!” explained the tweeter who was unfamiliar with Russian history.

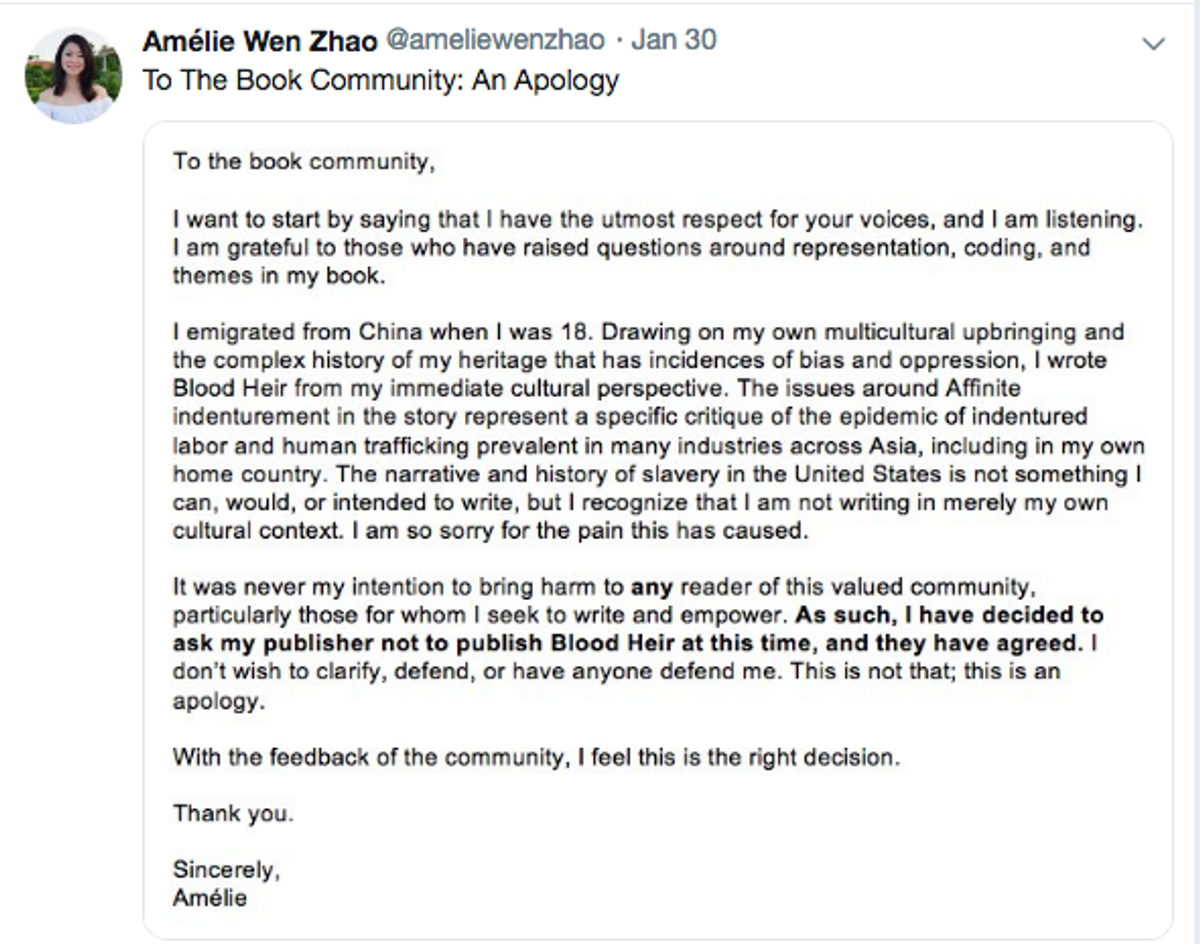

After a week or so of being held accountable, Zhao apparently had had enough. On Wednesday she announced that she had chosen to withdraw her already completed novel from being published. Her statement is quite telling:

According to Zhao’s own account, she simply wasn’t writing about anything like American-centered chattel slavery. Rather, the slavery references in her book stemmed from her concern with modern-day indentured servitude and human trafficking in the part of the world she grew up in. This, of course, renders even more questionable many of the critiques of her supposedly ham-fisted treatment of (the fantasy equivalent of) American slavery, and makes it even less likely she intended for May to be the approximate fantasy equivalent of a black character, rather than the approximate fantasy equivalent of (perhaps) an Asian one.

Fittingly for an episode driven by online rumor mongering, new rumors are now spreading that Zhao’s unpublishing wasn’treally about the social justice tribunal. During the pile-on, some people argued that on top of all her other sins, Zhao had plagiarized. The only “evidence” I could find of this, anywhere, was a one-sentence utterance from one of her characters, “Don’t go where I can’t follow,” which is a pretty well-known quote from The Lord of the Rings. In context, it’s more likely homage than plagiarism—there was zero chance it wouldn’t be noticed by Tolkien nerds, who are probably overrepresented among YA readers—and even if it is plagiarism, it’s a six-word misdemeanor. That doesn’t topple a “major” three-book deal. I reached out to Delacorte, Penguin, and Zhao’s agent to ask if she was being investigated on that or any other grounds that would add context missing from her statement, and didn’t hear back by the time this story was published.

Of course there’s a chance that more information will come out and change the storyline. But what matters is that many within the YA fiction world don’t need more information—they’re already celebrating their role as the righteous disciplinarians who, by revealing the text’s coded racism, compelled Zhao to unpublish her book and seek forgiveness. “This is a beautiful apology,” tweeted Oh. “Thank you for listening. I know that your book will be stronger for it. I wish you all the best.”

In a certain visceral sense, it doesn’t feel like Zhao’s trilogy could really be gone—it just doesn’t make sense that this was all it took. And maybe, as some online are already hinting, she will revise the book to make it more acceptable to YA Twitter—perhaps she can replace all that pesky material darkly inspired by modern-day human trafficking with references American Twitter critics find easier to process. Either way, this was a big deal. Surely other publishers will take notice and make decisions accordingly the next time a manuscript with anything bearing even passing resemblance to hot-button issues crosses their desk, even if it’s written by an author of color.

This episode is yet further evidence of two conflicting truths about contemporary online outrage dynamics: It demonstrates both that corporations should, as a general rule, simply ignore angry people online, in part because they are rarely a representative sampling of consumers or operating from a good-faith place of full context, and that online mobs trafficking in misinformation and outrage can have significant real-world effects.

We don’t know where Ana’s story might have led, but here is how this tale ends, for now at least: with a group of mostly American writers pillorying a novel few of them had read out of the misplaced conviction that the book was ‘about’ American slavery and handled that subject inappropriately; that therefore it was deeply racist; and that, further, its author was not only an offensive writer but a maniacally screenshotting danger to others. They spread those claims far and wide to the point where they were echoed and amplified by influential members of the literary community in question. As a result, the book, which was intended as a comment on contemporary slavery in a part of the world most Americans know nothing about, probably won’t be published and won’t give American readers a chance to read the perspective of an Asian writer inspired by an issue of urgent importance to many Asian people.

A couple common phrases from the argot of online social justice spring to mind here: Rethink this. Do better.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly attributed a quote to the wrong volume of the Lord of the Rings series. It has since been corrected – ed.