‘I Disagree With Him But I Love Him’

Niece of man saved by Dutchman who returned Yad Vashem medal says, ‘He is a righteous man’

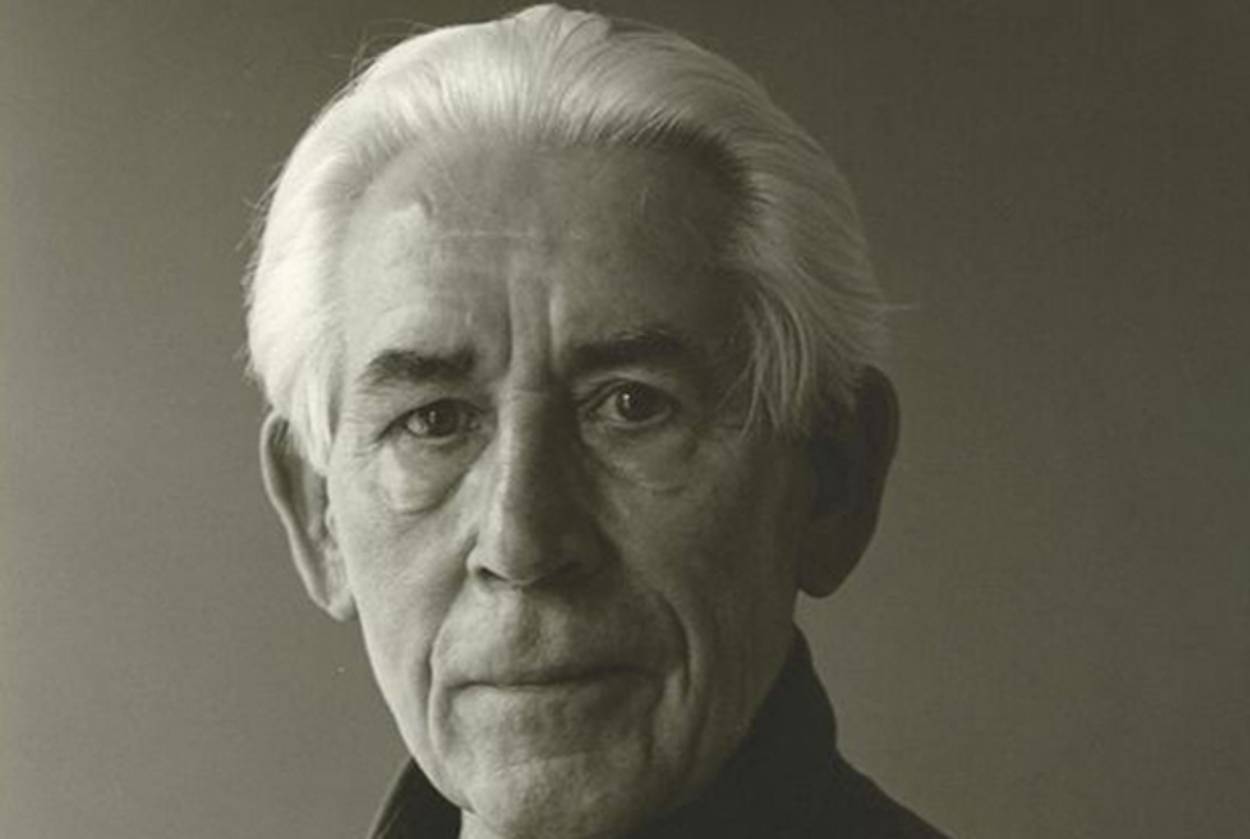

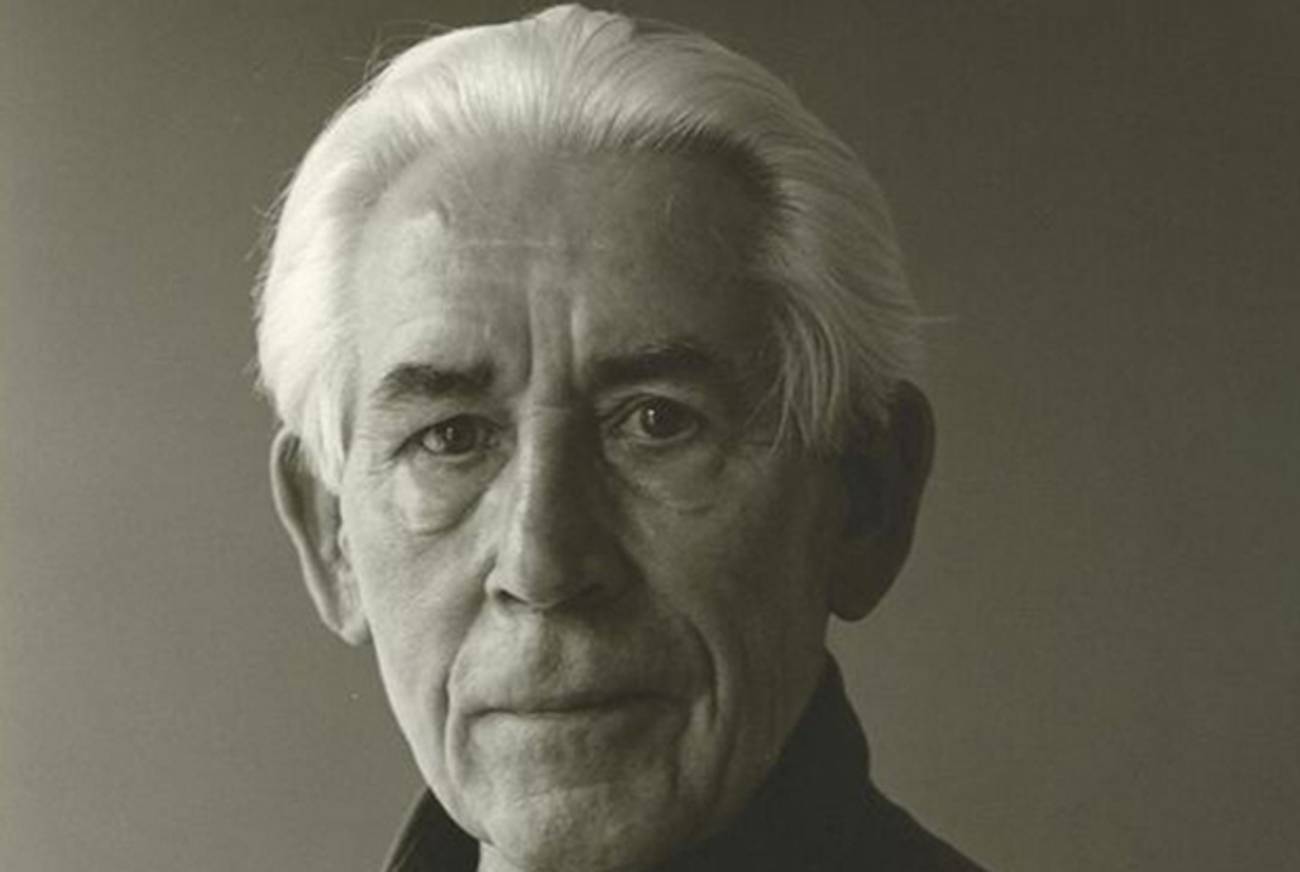

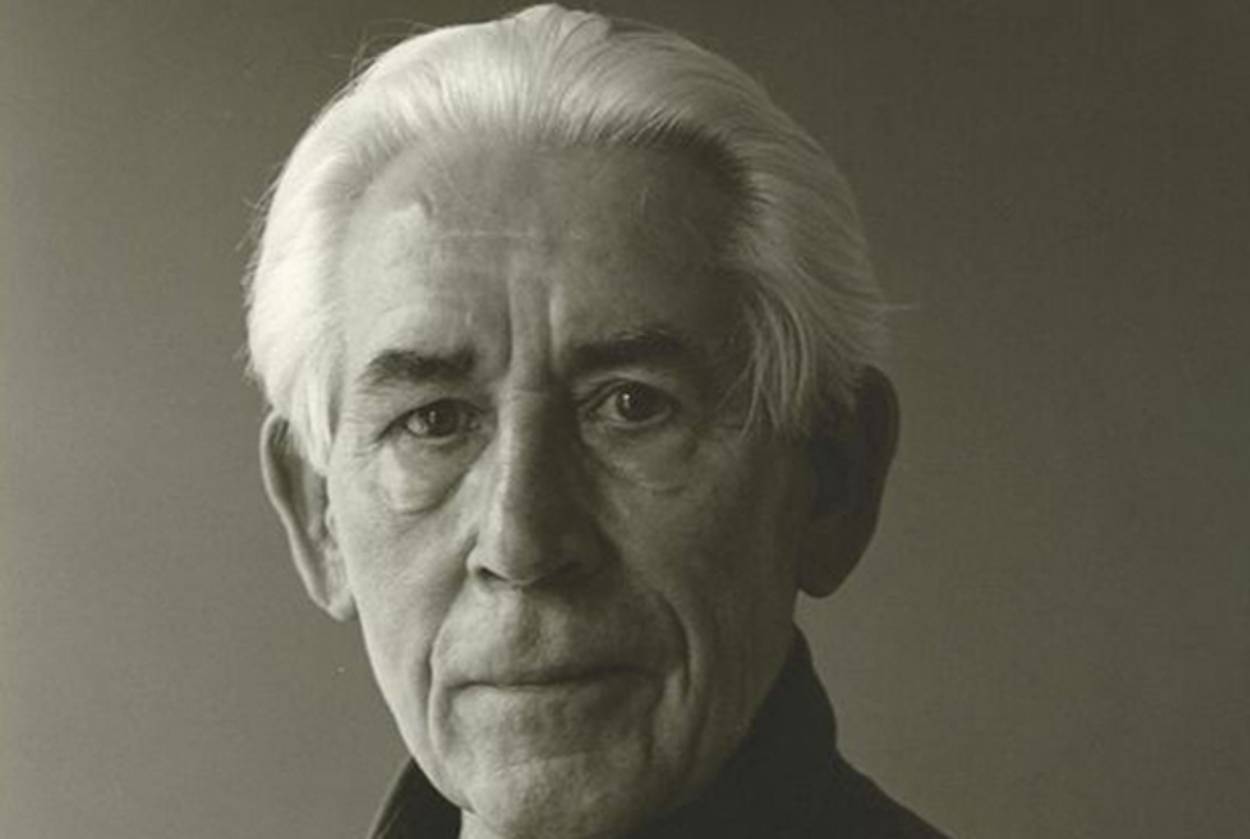

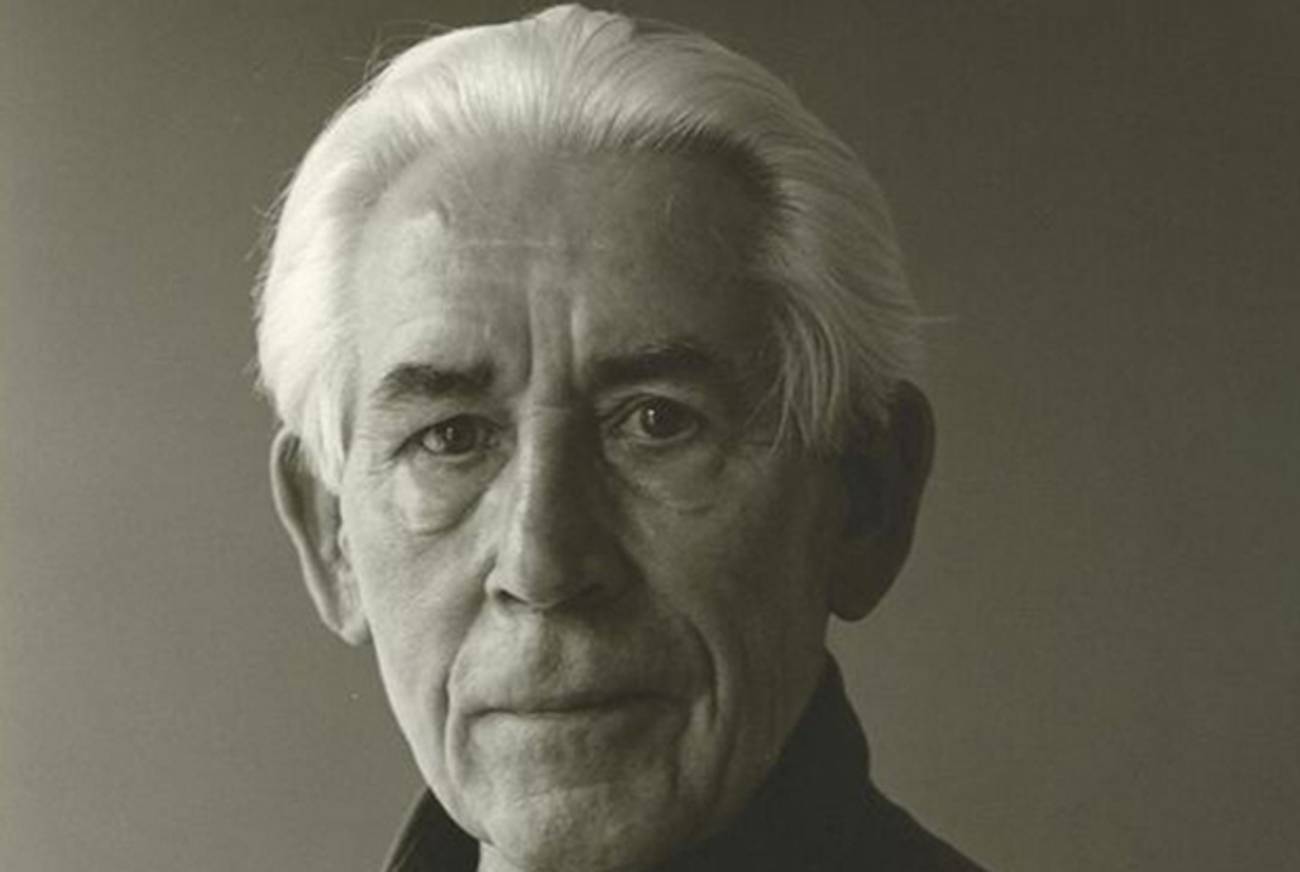

If it weren’t for the efforts of Rivka Ben-Pazi, the role Henk Zanoli played in saving her uncle Elhanan Pinto Hameiri’s life during the Holocaust might never have come to light, nor would the Dutchman and his late mother have been awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal from Yad Vashem in 2011 for his courage.

So when news broke last week that 91-year-old Zanoli had returned the award in protest of Israel’s operation in Gaza after six relatives of his were killed in an Israeli air strike in July, Ben Pazi was torn.

“He is a tzadik (a righteous man). He saved my uncle and I dont want to judge him during his pain and mourning,” Ben-Pazi told me in the first interview given by a relative of Hameiri’s. “I don’t agree with him, but I’m trying to understand him during this moment.”

Zanoli’s decision to return the medal followed the bombing of a house in Gaza on July 20th by the Israel Air Force that killed Zanoli’s great niece, three of her sons, and the wife and 12-year-old sons of one of her sons.

Ben-Pazi, who lives in Karnei Shomron, a Jewish settlement in the West Bank, said she still “loves” the 91-year-old for his deeds during the war. At the same time, she deeply disagrees with him and believes her late uncle, whose life Zanoli saved, would too.

“He probably would have written Henk a letter,” she said of Hameiri, who lived in Jerusalem until he died of pneumonia in 2007 at age 72. “I’m sure Elhanan would have called him, would have comforted him for his loss, but he wouldn’t have agreed with it [returning the award].”

Hameiri was a very private person, and his story of survival during the Holocaust was a mystery even to members of his family. He and his wife Leah, who died a few years before he did, never had any children, and after Hameiri’s death Ben-Pazi decided to research his story, spending the next five years piecing it together.

She began with his testimony in the Yad Vashem archives. There she managed to find and later contact Zanoli, who now lives in the Hague, and who, along with his late mother, Johana Zanoli-Smit, hid 11-year-old Hameiri in their family home from 1943 until 1945. Zanoli had managed to smuggle Hameiri (then named Elhanan Pinto) from Amsterdam to the Zanoli family home in a Dutch village.

Part of Ben-Pazi’s research involved corresponding with Zanoli through letters that were translated from Hebrew to Dutch and vice versa. After finishing the research, she self-published the book “Cry of the Humble” (“Tzaakat HaAnavim”), and had a synopsis translated into Dutch and sent to Zanoli.

Around that time Ben-Pazi asked Zanoli if his family had ever received any sort of commendation from Yad Vashem for their heroism. He told her they hadn’t, nor did they see any need to be thanked for their actions. Nonetheless, she contacted Yad Vashem and implored them to recognize the family as Righteous Among the Nations, a process that she said took about a year and a half.

She said she did so because their act of heroism wasn’t self-evident, explaining that Zanoli’s father was arrested for resisting the Nazis, marking the family as a target. “Despite all this they took a Jewish kid into their home, risking their own lives for two years to save him,” she said.

Zanoli’s mother became a maternal figure for Hameiri, Ben-Pazi said, and over the years her uncle kept in touch and visited the Zanoli family in Holland. Ben-Pazi said he was particularly close to Harry, Zanoli’s nephew, who was a baby during the war, and who lived with Hameiri in the years he was in hiding during. Over the years, Harry traveled to Israel a number of times and visited Hameiri, Ben-Pazi said.

Hameiri worked for decades at the Israel Museum and, after the Six-Day War, at the Rockefeller Museum in East Jerusalem.

Ben-Pazi is a 61-year-old retired schoolteacher with five children, including one who fought as a reservist in Gaza during the recent conflict, as part of a combat unit that extricates wounded and fallen soldiers from the battlefield.

She said of Zanoli, “the people of Israel owe him a lot,” adding that while “war is a tragedy,” this is one that Israel fought because it had no choice.

Another relative thinking about contacting Zanoli is Jerusalem resident Hanna Horovitz, Hameiri’s 79-year-old cousin. Her mother, Hameiri’s aunt, survived the war after she immigrated alone to Palestine in the 1930s. The rest of the family stayed behind, and other than Hameiri, Horovitz believes that virtually all the rest were killed in Sobibor and Auschwitz.

In 1951, after Hameiri immigrated to Israel, he stayed with Horovitz’s family in Jerusalem. He was a quiet, withdrawn boy with a heart condition who was very intelligent and “never would have believed anyone would write about him,” Horovitz said.

Asked what she thinks about the deaths of Zanoli’s family members in Gaza and his decision to return the award, she said, “For 13 years we’ve been suffering from the shelling, and now they’re building all of these tunnels. You can’t judge us, how can you live under shelling all the time?”

She added that her cousin Hameiri “would have said that to him also. He would say he’s sorry too, but also tell him all of this that I’m saying.”

In a letter to the Israeli embassy in the Hague, which he submitted along with the medal and certificate, Zanoli wrote that keeping the medal would be “both an insult to the memory of my courageous mother who risked her life and that of her children fighting against suppression and for the preservation of human life as well as an insult to those in my family, four generations on, who lost no less than six of their relatives in Gaza at the hands of the State of Israel.”

He also took issue with aspects of Israel beyond his personal tragedy, saying that the “Zionist project” had practiced ethnic cleansing and suppression of Palestinians and had “from its beginning a racist element in it in aspiring to build a state exclusively for Jews.”

Contacted on Sunday, Yad Vashem said of Zanoli’s decision, “we are sorry for his loss, and regret his decision to return his mother’s medal. The survivor passed away as far as we know.”

Ben Hartman is the crime and national security reporter for the Jerusalem Post. He also hosts Reasonable Doubt, a crime show on TLV1 radio station in Tel Aviv. His Twitter feed is @Benhartman.