Yes, Democrats, It Can Happen Here

Ex-British MP Ian Austin talks about the encounters with Holocaust survivors that shamed him into leaving the Labour Party

It was at Auschwitz that Ian Austin first realized he would eventually have to leave the Labour Party. The then-member of Parliament for Dudley North, a working-class constituency outside Birmingham, was visiting the Nazi death camp in 2018 as part of a delegation. In the hotel lobby, Austin was introduced to Ivor Perl, a Holocaust survivor and fellow British citizen, who asked Austin for his party affiliation. After answering, the MP was shocked when, instead of offering the deference to which he had become accustomed during a near-15-year career in the mother of all parliaments, Perl replied, “Are you not ashamed?”

“I was ashamed,” Austin confessed to me recently during a visit to the United States. Since his far-left colleague Jeremy Corbyn was elected Labour leader in 2015, Austin had been one of his most outspoken critics in the party’s parliamentary caucus, lambasting Corbyn for his extremism, sympathy for anti-Western dictatorships and terrorist groups, and decadeslong association with anti-Semites. But it was not until he was confronted by a survivor of the anti-Jewish genocide at the very cynosure of its industrialized, mass extermination that Austin understood his protests—no matter how effective coming from one of Corbyn’s own MPs—were insufficient.

The sense of shame was compounded by a similar encounter, occurring within weeks of the Auschwitz visit, in London’s Parliament Square. At an unprecedented protest against Labour anti-Semitism organized by the U.K. Jewish community, Austin saw another Holocaust survivor whom he had met years earlier at a commemoration event in his constituency. “The first political demonstration in her life and it was against the Labour Party,” Austin said, the humiliation still evident in his voice nearly two years after the fact. “And it was just obvious. How could you ever stand in an election with Jeremy Corbyn as the candidate for prime minister?”

It was not until the following February that Austin finally resolved that dilemma by quitting the party he had joined at the age of 16, and to which he had tied his political fortunes for almost four decades. “I joined as a teenager 35 years ago to fight racism,” Austin said, recalling the days when members of the fascist National Front terrorized immigrants in the economically depressed Midlands and northern England. “I can’t believe I had to leave it to fight racism.” Austin’s departure came amid a succession of fellow MPs abandoning Labour, all of them citing the anti-Semitism of Corbyn and his supporters as a major reason. Austin went one, albeit significant, step further, crossing party lines to endorse Prime Minister Boris Johnson and his Conservative Party in last year’s general election as the only way to stop Corbyn from entering 10 Downing St.

What effect these high-profile defections had on Labour’s disastrous loss in that election—it’s worst result since 1935—is impossible to quantify. But the belief that Corbyn was unfit to be prime minister (and that his anti-Semitism formed a crucial part of that unfitness) predominated. According to a post-election poll, for a plurality of traditional Labour voters who did not support the party in the last election, Corbyn’s leadership was the determining factor.. And if it was misgivings about Corbyn’s character which prevented Labour from assuming power, then Austin can claim a good share of the credit for giving substance to those doubts.

“In large parts of Britain there are no Jewish people, most people in Britain do not know any Jewish people, do not know the theory, the detail and the history of anti-Semitism,” Austin explained. But “when you talk to them about anti-Jewish racism, they get it, they know when something has gone wrong. … Ordinary, decent people stood up for the Jewish community. It was certainly a factor in what was a shattering defeat for Labour.”

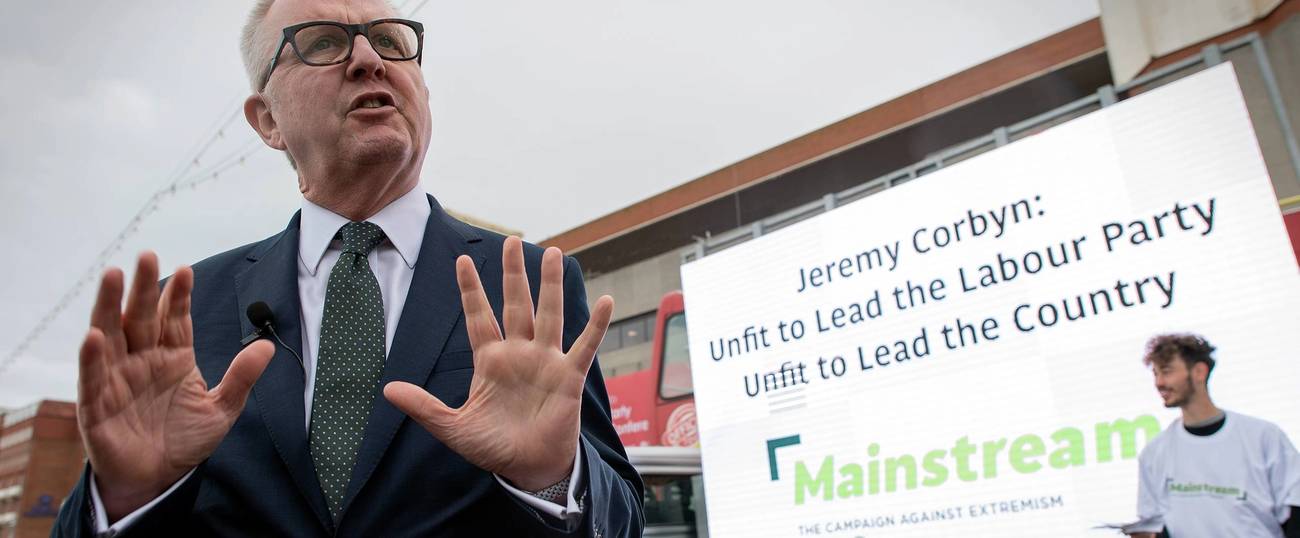

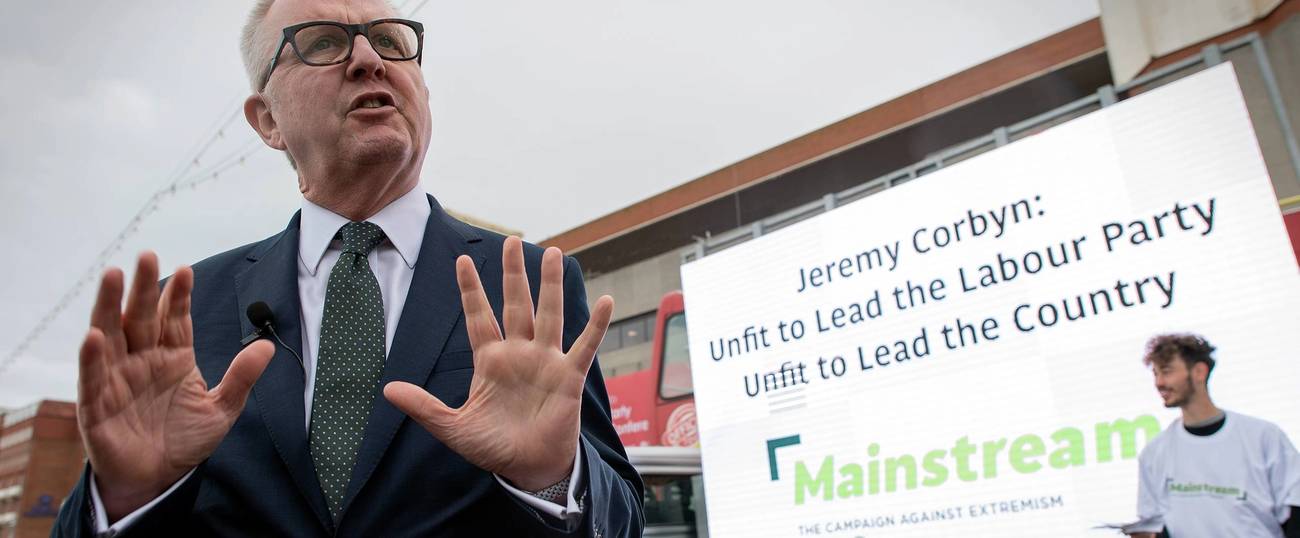

While it’s inspiring to hear that the mainstream (which happens to be the moniker of a new campaigning organization against extremism Austin founded) of British society was repulsed by Labour’s anti-Semitic putrefaction, there is little sign that the party itself fully comprehends the moral depths from which it needs to emerge in order to become a respectable party capable of governing again. Three out of four members say the anti-Semitism controversy was “invented or wildly exaggerated by the right-wing media” and Corbyn’s opponents to discredit him. None of the candidates running to succeed Corbyn has explicitly condemned the outgoing leader for allowing such a toxic culture to fester within the Labour Party, a culture that shows no signs of leaving. And it’s difficult to see how any of them credibly could. As Austin pointed out, “if you spent four years in Jeremy Corbyn’s top team and you’ve been saying you agree with Jeremy Corbyn 100% and just a few months ago you were asking people to make him prime minister, I think that disqualifies you.”

‘The idea that an institution as robust as the Labour Party and as important to Britain’s democracy could be so vulnerable to takeover by extremists and racists was unthinkable.’

For Austin, the anti-Semitism that has infected his erstwhile political home is personal: His adoptive father was a Holocaust survivor from the industrial city of Ostrava in Czechoslovakia. Though he was not raised Jewish, Austin has long been close to the U.K. Jewish community and was always an outspoken opponent of anti-Semitism. So when an anti-Semitic movement took his political party hostage, Austin knew he would have to speak out.

In their campaigns to succeed Corbyn, the Labour leadership candidates are expressing contrition to British Jews and promising that the nightmare they endured over the past four years will not be repeated. But with Corbyn’s acolytes occupying prominent positions throughout the party ranks, it’s difficult to see how anything short of a full-scale purge reversing what Corbyn wrought can redeem what was once Britain’s leading force for social and economic justice. “I think the Labour Party has got a huge amount of soul-searching to do,” Austin said. “It’s not like you had a policy that the public didn’t agree with. This was what had been a mainstream political party—a hugely important institution to our democracy—poisoned with racism against Jewish people. And there’s got to be the most profound apology. You can’t just sort of gloss over that and pretend it was someone else. This was a complete and utter disgrace.”

As is the case with any prominent Corbyn critic, Austin has been subject to vicious attacks by the leader’s cultlike followers. “I’m routinely told that I’m being paid by Mossad, that I’m part of some conspiracy,” he said. While he was still an MP, Corbyn supporters would protest outside his weekly constituency advice sessions and scream at him in meetings. “The hard truth is that they’re angrier at the people complaining about racism than the racists themselves,” Austin says of the hard-left faction that continues to dominate the party’s organizational structures. When I asked Austin if he thought Corbyn himself is an anti-Semite, a designation the mainstream media and even Corbyn’s many critics are extremely reluctant to apply, he bluntly answered, “What do we normally call people who say and do things that are racist?”

If what transpired in Britain sounds eerily familiar to liberals and Democrats on this side of the pond, Austin has a warning. “Five years ago, six years ago, nobody would have thought that what happened to the Labour Party was possible,” he said. “The idea that an institution as robust as the Labour Party and as important to Britain’s democracy could be so vulnerable to takeover by extremists and racists was unthinkable. But that should serve as a stark warning to people in the States that if that can happen to the Labour Party in the U.K., it can happen here.”

The far left, he said, “can’t be engaged with or tolerated in the way one normally deals with people with whom one disagrees.” The hallmarks of the hard left—the “secretive, closed, doctrinaire” methods, the “obsession with purity” and “rooting out internal enemies,” the “factionalism”—make compromise futile. (“It’s very important for us to create a black list of every operative who works on the bloomberg campaign,” an American progressive organizer with a large following declared in a since-deleted tweet, aping the Corbynista-style pronunciamento with a Stalinoid threat.) Furthermore, “it’s not good enough to say the hard left can’t win, you’ve got to argue why they shouldn’t win, why they’re wrong.” Austin points to the 2017 snap general election in which Corbyn, while losing, exceeded expectations. Because Corbyn’s critics had focused on electability rather than fitness, their case against his leadership was weakened.

Over two years later, however, Corbyn is on his way back to the parliamentary backbenches, not least because Austin did what practically no one in politics today had the guts to do: He acted in accordance with his professed values. In the summer of 2016, soon after Corbyn became leader, 75% of his fellow Labour MPs tried to remove him via a vote of no confidence. What they were in effect telling the country was that their own leader was unfit to lead Her Majesty’s Opposition, much less the nation. Yet at the moment of truth, when the electorate was presented with the chance to make Corbyn prime minister, hardly any of these MPs took the next logical step and withheld their endorsement.

Back in 2016, when Donald Trump was slandering Muslims and Mexicans, threatening to dissolve NATO, promising to “lock up” his political opponent, inciting his followers to violence, and generally rubbing salt in the country’s deepest collective wounds, many elected Republicans declined to endorse his presidential aspirations. But when the once-far-fetched prospect of political power suddenly became attainable, they too fell into line, which is where they have dutifully remained through each and every indignity, crime, and moral outrage of his presidency. “The appeal for unity is a powerful one,” Austin replied when I asked him why so few of his colleagues followed his courageous example. “The tribal loyalty. The desire for a quiet life. The hope that you can keep your head down and survive.”

Ian Austin did the right thing. Perhaps that’s why his political career is over.

***

You can help support Tablet’s unique brand of Jewish journalism. Click here to donate today.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.