It has been 50 odd years since I’ve believed in political communities—believed, I mean, without skepticism that pristine ideals could survive in reality’s trenches. I came of political age in two such communities forged in a time of trouble: one a 1967 New Politics convention that tried to put Martin Luther King on an anti-Vietnam Democratic presidential ticket; the other Eugene McCarthy’s anti-Vietnam Democratic presidential bid that aimed to force Lyndon Johnson out of the race in 1968. Both shared a unifying, higher cause: to oppose the war in Vietnam. But that wasn’t enough, since New Politics failed disastrously while the McCarthy campaign worked for a while and partly succeeded. Together, they convinced me that political communities are complicated constructions—different groups warring over who gets to claim a bigger mantle. When they work it’s because there’s enough organic, bottom-up assumptions holding together their different constituent parts to survive the inevitable shocks of internal schisms and outside resistance that hit any bold political venture.

This accrued skepticism means I’ve stayed away from a lot of proclaimed communities, picked and chose the way I subscribe to the rest, and never quite “fit” in—whether with the human rights community, the civil rights community, the peace community, or even the Jewish community. I threw myself behind the Democratic community when Al Gore was its standard bearer, but that was based on my read of the candidate and his policies and on my trust in the liberal—not left— Democrats who made up his base. Otherwise, even though I never admired John Kennedy, for 50 years I’ve been a subscriber to his one good line: “Sometimes party loyalty asks too much.”

Still, even 50 years since the scales fell from my eyes, I remain fascinated by the process: people coming together in the dark, trying to turn on a light for the rest of us. I’m especially fascinated now, because political communities have changed, these past 25 years, into things I don’t recognize: things that seem distant and sterile compared to when I was young. So I’m naturally curious about why they’ve changed, how, and what—if anything—the change means.

The community that fascinates me today is—seemingly—about as different from New Politics and the McCarthy campaign as you might imagine. Engaging it costs me nothing in energy, very little in time, and I can always be a part of it unless I unsubscribe. It’s the email Listservs of a constellation of groups associated with the Democratic Party, which I got on because I donated to Bernie during the 2016 Democratic primary—donated not because I wanted Bernie, but to hedge against Hillary. That donation led to emails, which led to links, which I clicked on, which led to more emails. Now, three-plus years later, I get as many as 20 a day, sometimes more. And I’m hooked.

Maybe you have to have grown up in the pre-internet era, or in the pre-television era, or simply in an era where society was constituted differently than our own, to be obsessed by these emails the way I am. But I am obsessed, because they seem to me to coalesce the political and social changes I’ve seen the last quarter century into a set of dispatches about the future: dispatches that pose an answer—to me, a dystopic one—to a question hanging over our era of social fragmenting. How do you build political communities in a scattered society swallowed by uncertainty—a society where there’s plenty to oppose, but seemingly no unifying assumptions to fall back on? My inbox offers one model.

Here’s what my inbox looks like on a given morning.

EndCitizensUnited.org sends me an email with the subject: “Please Read, don’t delete”

MARTIN, Republicans are launching heinously offensive attacks on Democrat Mark Kelly…Martin: the easiest way we can flip the Senate is to elect Mark Kelly…. We need to double down on our efforts to kick Trump’s Republican to the curb…or Trump will win. And Sunday’s deadline is so important, that’s why all donations are 400%-matched…Martin, if you remember the way you felt when we failed to flip the Senate in 2018, we need you to donate immediately.

A follow-up on Mark Kelly, from a different group, BOLD Democrats, with the subject line: “so so so close Martin” makes me think I’ve missed a credit card payment. It reads: “Cancellation Notice for Martin Peretz.” Then, the point: “350% match expires at midnight. Chip in $5 immediately to Elect Democrat Mark Kelly.” (I miss the expiration; Mark Kelly emails me for money the next day.) XXX

An email with the subject “Bad News from South Carolina: Serious” tells me that “We need you to rush $10 to Jaime Harrison’s U.S. senate campaign right away” because “the latest polls show us closing in on Lindsey Graham—we can’t let Trump fire up Lindsey’s supporters and RUIN our momentum!” Another email: the Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee Team writes warning me that “The GOP is very close to having a tyrannical level of control” (Where? I wonder. How?) and asks me to donate money to flip the Louisiana statehouse.

Progressive Turnout Project dials up the frequency:

Martin—Mitch McConnell is about to PUKE: If McConnell Loses, Democrats will be GUARANTEED to win the Senate. That’s why we’ve launched targeted ads to tank McConnell’s numbers and make sure he loses…And we’re gearing up to TAKE. HIM. DOWN!! Since McConnell vowed to block impeachment, we have Democrats willing to 350% match donations to fund our targeted ads for the next 48 hours.

Brady PAC sends me an alert:

Marty—have you been reading the news? Trump is turning to the NRA to save himself from impeachment. So a FLOOD of Brady PAC donors are stepping up to punish this president and destroy the NRA. Will you donate now?

Another Brady PAC email, this time on behalf of Cory Booker, uses the opposite idea with the same intent:

Martin—this news shook us to the core…gun violence is tearing our nation apart. Sadly, we can’t stand up to the NRA and their ultra-wealthy donors without your help. We need to raise $15,000 by 9 am tomorrow to keep our live-saving programs running.

(The “live-saving” is their spelling, not mine.)

I get an email headlined, “FLIGHT CONFIRMATION: Flight #2782422 Confirmed” and I naturally think for a minute I booked a flight and forgot, but it’s from Bold Democrats, and it’s about Susan Collins:

Martin — we are freaking out! FIRST: Senator Susan Collins cast the DECIDING vote to confirm Brett Kavanaugh. THEN: Collins TANKED in the polls. She’s now TIED with her Democratic opponent! SO NOW: Mitch McConnell is flying to Maine to BAIL OUT Susan Collins. McConnell showing up in person could STEAL this race from Democrats. So we need an emergency $2O,OOO before he touches down to show our strength! Martin, we’ll only win if you donate.. So we’re on our knees begging: rush a 3X-Matched donation today to end Susan Collins’ Majority →

(Can you imagine begging for this?)

Not all the emails ask for money. Lucy McBath writes “With Love” thanking her supporters “for donations of $1, $5, or $10 over email and social media to help me fight back against attacks from Fox News, Breitbart, the NRA, Donald Trump Jr., and national and local Republicans.” Andy Kim, via Team Andy, wants me to know about his work with Seniors (BREAKING: HUGE news Martin! Today Andy introduced a bill that would lower health care costs for senior citizens. ) “Team Jaime”, with the subject, “[be honest!], do you LOVE or HATE Mike Pence?” emails to let me know that “we need to defeat Lindsey Graham and stop Pence’s right-wing machine, but we need to know your thoughts before we get started” and asks me to take a poll. The National Democratic Training Committee writes with the subject, “Thank Nancy Pelosi,” asking me to sign a card:

Folks, Nancy Pelosi just took the first steps toward impeaching Donald Trump…So we’re sending Nancy a card to thank her for stepping up and doing what’s right.And listen, we want to make sure she hears from you. She’s going to love this.

Sometimes the emails remonstrate. Progressive Turnout Project sends another email letting me know that “You’re breaking Adam Schiff’s heart”:

Martin, last weekend we asked you to sign our petition and send Trump staffers to jail for ignoring Congressional Subpoenas. You did not sign. Now, Trump staffers think they’re free to break the law. Adam Schiff can’t do his job and conduct impeachment hearings if key witnesses are ignoring Congress. So I need you to sign on before 10:00 am tomorrow.

And Bobby R., from End Citizens United Research Department, writes me:

Hi Martin—last night was the FOURTH Democratic Primary Debate, and polling is ALL OVER THE PLACE. We sent our Post-Debate Questionnaire to all our Top Democrats to track opinions, but we noticed you still haven’t replied? Martin, I’m personally reviewing every submission so if we don’t get your response, our data will lead us to the wrong conclusions. So please, please complete this by midnight.

The subject lines are relentless: “Ruth Bader Ginsburg Fights Back Against Trump”; “Hillary Clinton SLAMS Trump (amazing!)”; “Breaking on CBS: Lindsey Graham made a Huge Mistake”; “Elizabeth Warren just COMMANDED Democrats (wow…she’s absolutely right)”; “Joe Biden Approval Poll: Martin’s input REQUIRED”; “Mark Zuckerberg + Lindsey Graham: EXPOSED”; “McConnell is TOAST: Martin, this news inspired us”; “Hillary Clinton is disappointed in you” (really, she’s been disappointed in me since 1994.)

The content is breathless. “NO NO NO !!” an email tells me, “Trump COLLUDES with Fox News, sends Bill Barr to Meet with Fox News Executive.” “Katie Porter is GASPING FOR AIR” another blares. “National Republicans are PUNISHING Katie Porter for supporting impeachment—they’re DROWNING her in Attacks.” Another announces: “Nancy Pelosi Just CRUSHED Trump with Something huge (OH MY GOD, MARTIN! Nancy Pelosi just SLAPPED Trump with a huge bill to take down his presidency!)” And then, just in case I’ve missed the point: “Trump will hold MASSIVE Texas Rally tomorrow to DESTROY Colin Allred.”

And, from Bernie Sanders’ Our Revolution, more cogent and more paranoid:

Despite the desperate attacks from flailing, corporate-backed candidates on Bernie’s vision…our movement—including AOC, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib—knows the truth: Bernie is here to directly challenge the power of multinational corporations to buy influence through donations.

The groups sending these emails are not telemarketers. The Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee says that it’s “fighting to elect local Democrats, retake statehouses, and end right-wing gerrymandering across the country. We count on our supporters to get involved and take action in their communities.” End Citizens United is dedicated to “electing Democrats, transforming our broken campaign finance system, and ultimately ending Citizens United.” Progressive Turnout Project is “proudly dedicated to doing what we do best: connecting with voters one-on-one to increase Democratic voter turnout.” The National Democratic Training Committee is “teaching Democrats how to adapt winning tactics to their own race. Free online campaign training for Democrats running for office. We’ve got your back.” Bold Democrats “is dedicated to ending Donald Trump’s presidency, taking back the Senate, and electing a wave of diverse Democrats. We’re the largest organization working to engage Latino voters—that’s how we’ll take down Trump.” And, though Bernie’s Our Revolution is paranoid, paranoid is the style of the increasingly hard Left. In other words, these groups are mainstream, which makes what they’re sending me all the worse—because their messages are closer to pathological than any “mainstream” message I’ve ever read.

Most of them try to convey a tremendous sense of urgency, based on imminent victory or crucifixion—they’re either “gearing up to TAKE. HIM. DOWN!!” and “kick Trump’s Republicans to the curb” or “GASPING FOR AIR” and “on our knees begging.” Most of them use the pretense of poverty— “Sadly, we can’t stand up to the NRA and their ultra-wealthy donors without your help”—except when they’re using the pretense of power—“a FLOOD of Brady PAC donors are stepping up to punish this president and destroy the NRA.” Many of them promise “matched donations” of up to 400%, which means they’re being bankrolled by “ultra-wealthy,” unrevealed donors of their own. The capitalization and formatting are, well, offputting. The writing is unspecific—Republicans are close to a “tyrannical level of control”; Republicans will “steal this race from Democrats.” How? And the urgency is almost indescribable…and it’s only November 2019. Imagine what the emails will be like in November 2020.

What’s most telling, to me, is how few of the emails tell you where in the country the candidates are from until the message’s end. They’re not concerned with local issues but with “Fox News, Breitbart, the NRA, Donald Trump Jr.” and they assume you’re a committed supporter who will donate for one of “the team” without inspecting the message too closely as long as they conjure the right enemies. So even though they’re not technically telemarketers, they’re marketing, based on whatever their data—their “polling” and “post debate questionnaires”–have told them and they play off people’s most primal impulses: diminishing the pragmatic gray space of actual politics into black and white stories framed so luridly that they sound like pornography, or else like manic religious imagery for the disempowered to grab hold of. They’re community creation exercises in the broadest strokes: If you believe x, y and z, you’re on our side.

These emails are not outliers but purer distillations of something happening out there around us, in the everyday. It’s not only that the other “side,” Trump’s Republican fundraisers, use the tools—they do. It’s that zero sum, moral fervor is the tone of national politics—not just on Facebook or Twitter, which I don’t look at, but The New York Times opinion pages, which I do. A random sampling of headlines last month:

“Tech Companies are Destroying Democracy and the Free Press”; “Trump Is a Bad President; He’s an Even Worse Entertainer”; “Racists Are Recruiting: Watch Your White Sons”; “It’s 2040: We Need to Keep Abortion Legal in New York” “Impeach the Malignant Fraudster”; “Republicans Only Pretend to be Patriots.”

And that’s not even to mention the slug lines from the Democratic primary debates this year, where anything but open border policy and anti-Republican rhetoric is the same as heresy—a reason for shunning.

How do you build political communities in a scattered society swallowed by uncertainty—a society where there’s plenty to oppose, but seemingly no unifying assumptions to fall back on?

Some of these inflations are products of Trump, but they’re not just products of Trump—or he’s a symptom, not the cause. When we saw the darkening, sanctifying tone in the ’90s and early 2000s, we called it a social coarsening and blamed technology and moral decline; now, when technology has swamped us and traditional morals seem quaint, we call it tribal divisions and blame psychological maladies and social stratification. Really, what we’ve seen for a quarter century is itself the symptom of something bigger: Increasingly desperate ideologizing to create communities as the old organizing edifices, the blend of the local and national that many of us grew up with, have slipped away.

A half century ago, when I tried my hand for the first time at political communities, we had labor unions and ethnic enclaves and local newspapers (my Yiddish enclave in New York had half a dozen broadsheets for itself, and the city was serviced by a dozen and a half more). We also had a white middle class that had fought a war of virtue against one totalitarian state and was helping to fight a Cold War against another. These were the building blocks on which groups of ideas and ideals could be built—Italians and Irish, Jews and Blacks, California Boeing operators and Midwestern GI Bill recipients were New Dealers, patriots, Democrats, and recognized each other as such, as much out of shared experiences as out of broadly articulated beliefs. Within these accustomed notions, pragmatic or even philosophical differences could be sorted.

Now we’re a nation of buyers and self-expressers who move around; politics is the province of national interest groups and institutions; and beliefs and ideas are, seemingly, all we have to identify us—so mobilizers cram them into the simplest possible boxes and beat them over people’s heads. Of course politics has become purely top down community building: Where do you start if you try to build from the bottom up? No wonder ideological beliefs are so tightly held by the believing: Without them, what else do we have?

Fifty years ago, when I first started building political communities, there were glimmers of this possible future.

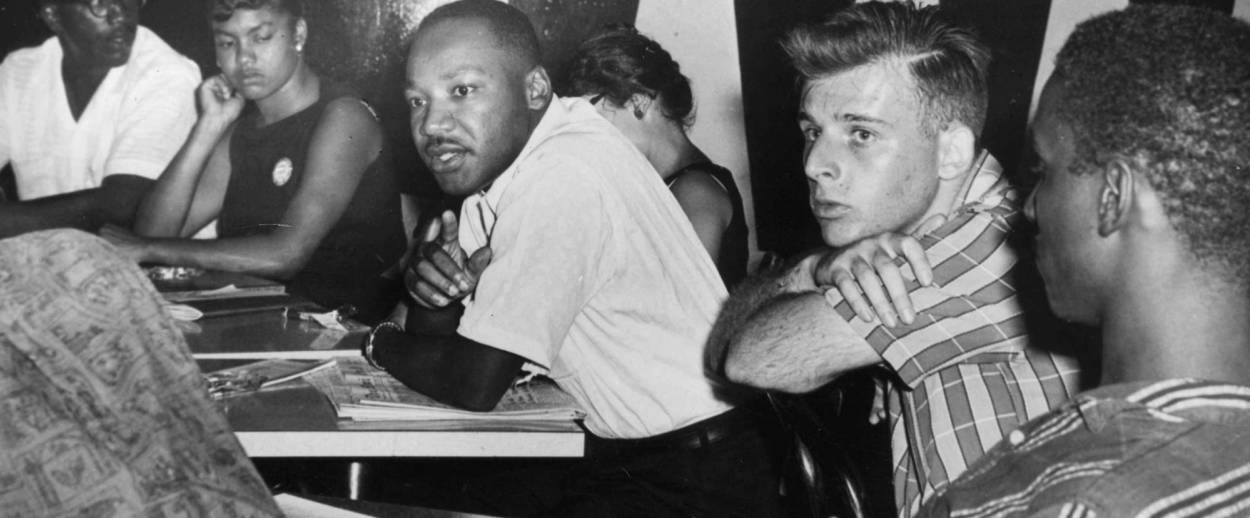

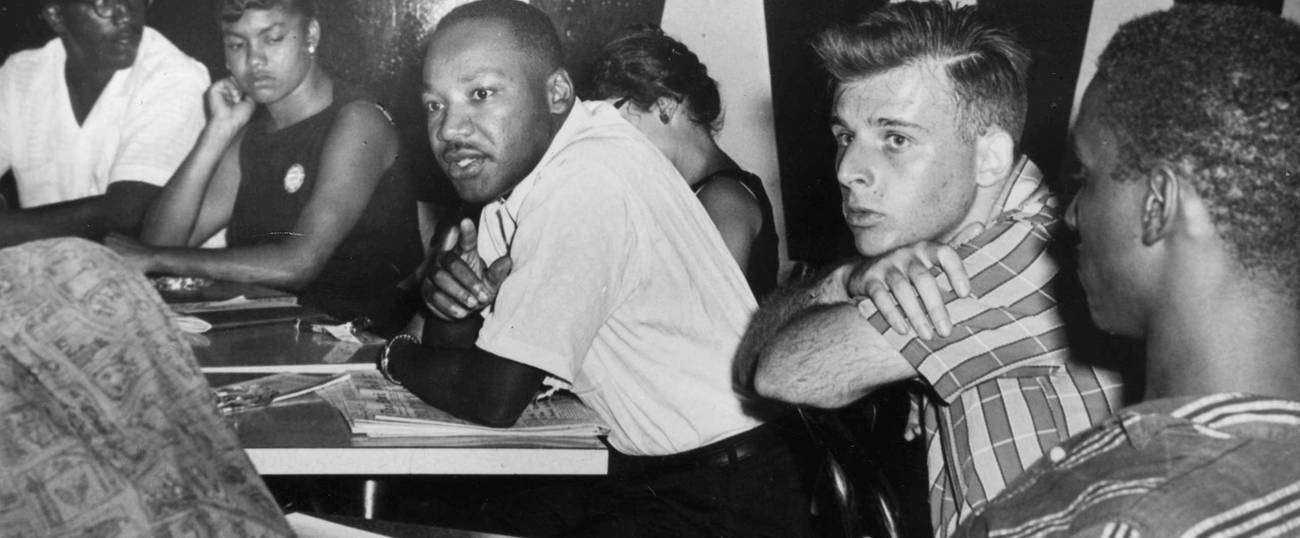

In 1967, New Politics seemed like a clean way to use the momentum of the Civil Rights Movement to channel the passion of anti-Vietnam activism: black middle class and white Civil Rights liberals, joining up with white student protesters and Democrats who were increasingly distrustful of the war. We would convene in Chicago in late August; Martin Luther King would be our proposed presidential candidate; Benjamin Spock—an old line progressive Protestant, writer of The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care, doctor to millions and darling of the campus professoriat—our vice president. From there we would plan to launch an independent third-party bid or compete in the Democratic Party primary against the hated and demonized Lyndon Johnson.

But we destroyed ourselves before we started by deciding to let in every antiwar group that wanted to join. On paper, this meant inclusivity. In practice, it meant that liberals, social democrats, democratic socialists and Freedom Riders who believed—in theory at least—in electoral democracy were sharing space with Maoists and Leninists and anarchists, who believed in change at the barrel of a gun. Predictably, the convention devolved: Black and white anarchists and Marxists roamed through the halls of the Palmer House Hotel in Chicago, forcing through motions that voted the convention defunct in the name of politics of the street. Martin Luther King got shouted at during his speech that was supposed to open the convention, and his top deputies, Andrew Young and Julian Bond, left soon after.

Nobody took anything seriously, but they thought they did. Friends of mine, Jewish liberals raised in comfortable homes, were suddenly talking about the spiritual crisis of the suburban middle class, or advocating revolution. Renata Adler was there, reporting for The New Yorker, and reading her piece, “Radicalism in Debacle,” I see again, in print, the words I heard ricocheting around me 52 years ago, full of total commitment and free of any real meaning:

“After four hundred years of slavery, it is right that the whites should be castrated!” That was one white Jewish delegate. “We are just a little tail on the end of the very powerful black panther, and I want to be on that tail—if they’ll let me.” That was another. If the rhetoric wasn’t emotionally castrating, it was vaguely idealistic—“this convention, with all its beauty and power,” one speaker proclaimed; “this Chicago palace, with the country looking on,” another said—or else just vague: “Brothers and sisters,” the chairman of one of the “sessions” announced, “the purpose of this convention is to enable the delegates to do what they wish to do.” And, shockingly to me, the student liberals a few years younger than me—I remember Sidney Blumenthal being one who went along with the nonsense. “Don’t let’s get uptight about co-option” is what one attendee told me when I expressed my concerns that the convention was being taken over by hard-liners and kooks. There was something sloppy about it or indulgent; and even a certain sense of innocence. It wasn’t politics as pragmatic compromise and ferocious debate, which is what I’d grown up with; it was politics as spiritual uplift and raw force, which was something I’d never seen.

But the problem with New Politics was simple and so was the solution—we’d included the wrong groups, a mistake that got remedied in Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign: By definition, anyone who participated believed in electoral politics as the means to change. So the young men and women who’d grown up in rooted communities but had come into a nationalized postwar America—who supported Civil Rights, opposed Vietnam and wanted to clean up the inner cities that the highways had cut off from prosperity—could come together “to speed along by natural means” America’s evolution.

Elite Protestants, Irish, Jews, Italians, socialists, liberals, women and students convened for Gene. His policy stances—the first proposal by a presidential candidate for some kind of guaranteed income for the poor; proposals to curtail a distant and unaccountable defense apparatus; support for unlimited spending in elections as long as the entity doing the spending disclosed itself—reflected the varied, pluralist character of his constituents. Gene’s campaign didn’t quite work: African Americans went for Gene’s rival Bobby Kennedy and union bosses went for Hubert Humphrey. But it looked like it could have. And though we thought that Bobby was duplicitous on racial issues, and Humphrey was hidebound in an earlier era, the support for each candidate from the different communities was organic, not manufactured: forged in the scrum of actual political fights.

The advertising for the campaigns was, it almost goes without saying, lugubrious: Television was just two decades old, and the first televised debate had happened eight years before. “Clean Gene” was the most daring slogan we came up with, and that was OK. There was a certain almost old-fashioned gentility to the campaign: When Bobby Kennedy was assassinated in June, killed by Palestinian refugee Sirhan Sirhan, a stricken Gene stepped back from active campaigning, and Hubert Humphrey, who was not a bad or duplicitous man, got the nomination. When the campaign was over, even though we hadn’t gotten what we wanted, it felt to me like the mistakes of New Politics were at least half buried.

The next time I saw the New Politics combination was a quarter century later, when Hillary Clinton, a former student activist from Wellesley who’d become a corporate lawyer, came to Washington as First Lady preaching a theory of “politics of meaning” which held that contemporary life had become so atomized and confusing that Americans needed a new communitarianism to give their lives purpose. Really, this was updated New Politics—Hillary, like her friend Sidney Blumenthal (who, alas, worked for a time for me at The New Republic), had swum in those waters since her famous 1969 commencement address at Wellesley, when she talked about her cohort’s “feelings that our prevailing, acquisitive, and competitive corporate life … is not the way of life for us” and proposing “more immediate, ecstatic, and penetrating modes of living. …”

In 1993 she spoke at University of Texas about “a crisis of meaning” in the same vein:

What does it mean in today’s world to pursue not only vocations, being part of institutions, but to be human? … I think the answer to … who will lead us out of this spiritual vacuum … is all of us … it requires each of us to play our part in redefining what our lives are and what they should be. And coming off the last years when the ethos of selfishness and greed were given places of honor never before accorded in our society it is certainly timely to ask ourselves these questions.

Like the old New Politics, these were ideals without much concrete meaning. But though the ideals were vague, the model for the “community building” was very specific: government action to create solidarity along the efficiency theories of the consultant W. Edwards Deming, an expert in the rebuilding of postwar industrial Japan, which had become popular in the growing American corporate sector. To make workers more productive, Demings said, you had to move away from the “I” and toward the “we.” It was a vision of work as an orchestra in which every member played a part, where workers worked harder because the conductor made them feel that their voices were being heard. A year earlier, in 1992, Bill Clinton had run a presidential campaign that relied heavily and unprecedentedly on focus groups, and Demings’ approach was similar in kind: Gauge the workers’ general sentiments, then craft a messaging line to sell the program you wanted them to buy in the first place. This wasn’t, needless to say, an idea of political community I believed in.

It was politics as vague spiritual ideal, with concrete programs pushed through not by street force but by the force of the new management styles and administrative structures that defined modern America.

Hillary’s application of Demings’ idea was to reforming the health system, which made up one-seventh of the American economy and had myriad different interests involved—doctors, both specialists and general practitioners, nurses, drug companies, insurers, hospitals, people with health care, people without. She put the project under the control of another college activist turned consultant, Ira Magaziner, who acted like a data-oriented consigliere looking to implement management’s program rather than a legislator looking to craft a bill addressed to actual constituents, and made the health care planning sessions he led secret. When a coalition of physicians sued for greater transparency, Hillary fought them in the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. When a Democratic congressman suggested an alternative plan other than one which mandated universal coverage for all, Hillary said, “We’ll crush you.” When Daniel Patrick Moynihan, who’d legislated for the poor his entire life, urged her to settle for a provisional bill, pointing out that the Kennedy-Johnson programs she was looking to as models had passed with sweeping public support which her husband didn’t have, she ignored him.

What scared me about Hillary’s project was the same thing that had scared me about New Politics: it wasn’t politics formed by a collection of different interests that represented America, it was politics as vague spiritual ideal, with concrete programs pushed through not by street force but by the force of the new management styles and administrative structures that defined modern America. We know what’s good, and if you cross us, you’re bad. You’re on the team, or you’re off it. In retrospect, it was a new style of politics played by a new kind of politician. They weren’t quite like the young liberals I’d seen in ‘67. Hillary’s people were more suave, less scattered, ’60s activists still sure of their virtue who now knew how the game was played. They were from the upper-middle classes; educated in the Ivy Leagues in a certain way of thinking about the world; successful in corporate America but convinced of their place on history’s correct side. And this meant they weren’t much interested in dissent.

I was running The New Republic, which had been the first major magazine to endorse Bill Clinton in 1992, and we dissented: I thought that a bill remaking this much of the American economy, done in this kind of secrecy, would inevitably require so much tinkering after it passed that the practical effect would be to take away Americans’ health care choice. We came out strongly against Hillary’s health care plan: We ran a piece, really a provocation, by Betsy McCaughey titled “No Exit,” an outline of a worst case scenario, the taking away of health care options, that she treated like a certainty. The shockwaves from the piece were immediate. Democrats who were doubting the plan in private had an excuse to jump, Republicans had a weapon—a liberal weapon at that— to pummel the plan with, and wavering Democrats pummeled by Republicans in an election year had another reason to withdraw support.

Not a lot of my liberal friends shared my opinion: People I respected—Sean Wilentz, say, and C. Vann Woodward, brilliant historians who wrote for The New Republic—were very much pro-Hillary. Woodward, whom I’d known since he taught me Southern history in a summer program at Brandeis in 1956, wrote me a critical note about our coverage of the White House. (The message is in a new collection of his letters.) I took the note seriously but it didn’t sway me an inch.

It didn’t sway me because I knew what I’d seen at New Politics in 1967. And it didn’t sway me because I remembered my Yiddish enclave in the Bronx, where politics wasn’t a pastime, but entailed commitments; where distinctions between social democrats and democratic socialists led to fisticuffs and broken friendships. That kind of personalizing of politics, the intense realness, isn’t an American phenomenon—it’s the phenomenon of a diaspora from places where political loyalties determined life and death. And members of the diaspora, people who’ve grown up that close to political action, have a nose for political fakery—for sterile, depersonalized exercises in crowd control. If Hillary’s New New Democratic Politics was anything, it was that: a fake community, running on fake emotions, imposed from above.

Fast forward a quarter century, add the advent of email, and the political fakery I saw with Hillary is inundating us completely: ping after ping in my inbox transmitting the ethos of modern Democratic progressivism. “We’ll crush you” or “TAKE. HIM. DOWN” is the political style; $5 donations matched 400% by anonymous millionaire-zillionaire donors is the political practice; a Manichean but vaguely worded struggle against the “heinous” forces of “greed and selfishness” is the ad copy-inspired political program. The only alternatives to this are a hard-left world of anti-corporate solidarity struggles, or else Donald Trump. And, taking Hillary’s logic, this evolution of politics from bottom-up-pragmatic to top-down-theatric makes sense: If contemporary America has really become a country of lost souls searching for meaning, we’ll take any meaning at all.

Except that’s not what America is: We do have meanings, multiple ones, they’ve just been obscured by the management theory nonsense and the ideologized political noise. This is still a country of ethnic groups, and distinct regions, and myriad cultural dispensations: The black experience in Little Rock isn’t the same as the black experience in New York; Jews in Colorado live differently than Jews in Florida; Midwesterners go to church more than Northeasterners. Differences are alive here, no matter what the voices on the airwaves might say. Immigrants like the ones who formed my Yiddish enclave in New York still come here. A year ago, underneath another endless panicky Trump headline, the Times reported that the “foreign born population in the United States has reached its highest share since 1910 … and the new arrivals are more likely to come from Asia and have college degrees than those who arrived in past decades.” Hispanics and Africans come as well, and Syrians and Poles. This doesn’t always make for a politics or a society without discord—but it makes for an actually inventive, always new, truly as opposed to categorically diverse, ever-expanding place.

Of course, we’re not the same country as we were 50 years ago—we’re not rooted like we were, we don’t have the old structures to fall back on. We live differently: We’re united by what we buy and what we watch and how we travel, and we self-express in ways that were unimaginable when I grew up and men put on suits to ride the subway. This is a world whose foundations—the interstate, mass advertising, television, the suburbs—were set during my childhood, but which didn’t shape my deepest impressions, so I don’t relate to it emotionally. Really, people like me are caught between the old world and the new; although we benefited from the old order and also from the new freedoms, we see the problems of both.

The problem I see is basic but big: We once had a representative politics, but we’ve lost it and it’s clear that the new unrepresentativeness is not just a feature of the Democratic Party—it’s a feature of the Republicans, too. When I hear that America is a land of churches and virtuous entrepreneurs from Donald Trump, a president who uses his power to make a profit for his hotels, it doesn’t register as true. Certainly, we’re not Hillary’s country of lost souls needing public help to fight greedy capitalists—most of whom, to judge by their political donations, supported Hillary. But we’re also not Trump’s country of upright traditionalists oppressed by the cosmopolitan elite. You wouldn’t know it to read a mainstream newspaper or open a political email, though, because the parties are caught by ideologizing structures bigger than themselves. We’re all caught.

Still, I see building blocks for real political communities all around me. To pick three dissenting, politically minded, socially influential blocs I know well: There are liberals who care about issues like the environment and social welfare but who’ve come to see Left progressivism as an excuse for statist control. There are Jews who’ve kept their inherited liberal concern for the least advantaged but feel alienated from Democrats who muzzle dissenting opinions, and who make up history, in the name of social justice at home and world peace abroad. And there are Republicans who have sympathy with the anti-top-down backlash Trump represents but think his worldview is too reactionary and corrupt to ever really work. None of these groups completely add up with the other, but real political communities don’t ever get formed by groups that match in every respect.

Here I go back to what I learned 50 years ago. To really work, political communities have to include groups with enough priorities in common to hang together; to be tied to reality on ground; and to have enough force behind them to survive backlash from without and within. This last is especially important today: We live with a disjointed, disjunctured “public square” where the first battle is calmly, clearly, picking the right fights and the right issues to cut through the noise. And the noise is real, and it won’t go away: the noise of top-down, imagined communities operating on data-crunching and zero sum political force.

“We’re sorry Martin,” End Citizens United writes me tonight, not looking for money but conjuring up one of those imagined communities, this time via focus group:

It’s official: Elizabeth Warren is our new Democratic 2020 front‑runner…but there is still time for another candidate to soar to the top. All of our polling data is now void: if we do not figure out who our members support, we may invest in the wrong candidate. So please take 60-seconds to complete our crucial updated Primary Poll before MIDNIGHT >>

No, thank you. I’ll pass.

Who, out there, will make a real political community? Who are the Americans that will turn on a light in the dark?

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.