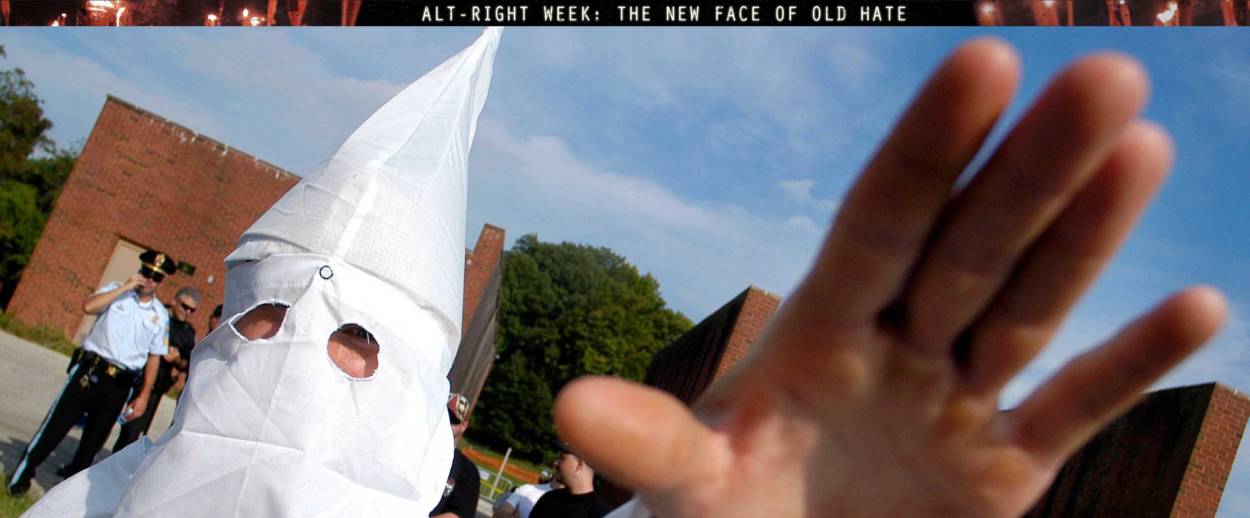

Introducing Alt Right Week

A deep dive into the movement, its troubling ideology, and its likely future

What, exactly, is the alt right? What are its ideological foundations, and who its founding fathers? Where did it rise from, and where may it go?

These are questions we’ve been reporting since at least 2015. And this week, as 2017 draws to an end, we’d like to pause and focus once more on addressing them at length. Throughout the week, we’ll be reposting some of our most relevant pieces on the alt right, as well as some new and unsettling ones.

What is the America far right? How many are in its ranks, and who, exactly, are they? James Aho takes a close and disturbing look at the movement. “Right-wing insurgencies occur once every 30-years or so,” he writes. “With the exception of the antebellum South, however, only a small portion of a given generation is drawn to them. So what is it that differentiates joiners from the rest? To begin with, there is little evidence for the popular theory that right-wing extremists are abnormally SIC: stupid, isolated, or crazy. On the contrary, they appear to have attained levels of formal education comparable to their more moderate peers. And even the most vicious among them who, if not dead, are moldering in federal prison, cannot be shown to be clinically insane.”

Writing about Trump’s presidential candidacy in December of 2015, Paul Berman mused on the nihilist pleasures of sheer hate: “grandeur,” Berman wrote then, “can be emotional. And so, the followers indulge their urge to hate. The Donald tells them that hatred is OK, and they yield to it. The wonderful thing about hatred is that it does not require a particular object. Any object will do.”

Some of Trump’s supporters, however, are a bit more specific in their hatreds. Of those, including the cadres who marched on Virginia, many see a retired Jewish professor named Paul Gottfried as an intellectual inspiration. “Gottfried doesn’t resolve the alt-right’s contradictions so much as he embodies them,” wrote Jacob Siegel. “He’s a sniffy traditionalist, a self-described ‘Robert Taft Republican,’ with a classical liberal bent, and a Nietzschean American nationalist who goes out of his way to exaggerate his European affect. He opposes both the Civil Rights Act and white nationalism. He’s a bone-deep elitist and the oracle of what’s billed as a populist revolt.”

Speaking of Nietzsche, the German philosopher is having a moment. In our new and wild political landscape, radicals on both the left and the right are finding something to love about the thinker and his ideas, wrote Guy Elgat: “The secret of Nietzsche’s appeal to people from opposite ends of the political spectrum is thus revealed: To the radical right, it is his rejection of equality and the democratic ideas that are based on it that is scintillating and rings true (besides his often and—as I have argued—misunderstood flirtations with the concept of race); to the left, it is his anti-essentialism with its emphasis on the plastic nature of identity that promises liberation from societal oppression. But, as it is typical in politics, the catch is that each side, to maintain its political ideology, has to reject the other’s Nietzscheanism: The radical right cannot easily accept the idea that identity, including racial identity, is dynamic and malleable, and the left, in order to promote its progressive agenda in the democratic public forum, cannot easily give up on the idea of the moral equality of all.”

More contemporary German history offers useful insights as well. The Weimar Republic, wrote Eric D. Weitz, showed us the dangers of traditional and radical conservatives learning to speak the same language. “That is the lesson from the right-wing populist upsurge in Weimar Germany, which culminated in the Nazi assumption of power,” Weitz argued. “The political language of fear and hostility directed at “foreign” elements (never mind the fact that many and even most of those so-called foreigners had been residents and citizens for generations) enables moderate and radical conservatives to come together. The moderates make the radicals salonfähig, acceptable in polite society. That is the real and pressing danger of the current moment.”

And as a new and troubling history tells us, the Nazis themselves looked at America for inspiration. “In the 1930s,” wrote David Mikics, “the American South and Nazi Germany were the world’s most straightforwardly racist regimes, proud of the way they had deprived blacks and Jews, respectively, of their civil rights.”

What, then, might we do about this ascendant hatred? Any effort to combat white supremacy, Eric K. Ward reminds us in a new piece published today, must include fighting anti-Semitism as a core tenet. “I developed an analysis of anti-Semitism but not because I wanted to smash White supremacy,” he writes, “but because I wanted to be free. If we acknowledge that White nationalism clearly and forcefully names Jews as non-white, and did so in the very fiber of its emergence as a post-civil rights right-wing revolutionary movement, then we will all be forced to recognize our own ignorance about the country we thought we lived in. It is time for us to have that conversation.”

From the editors of Tablet Magazine.