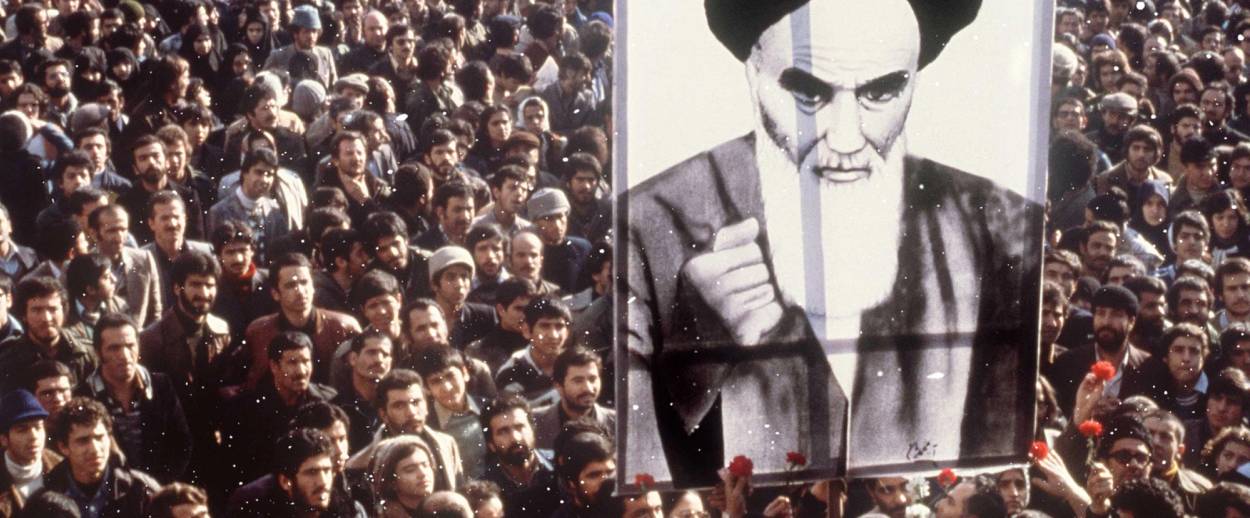

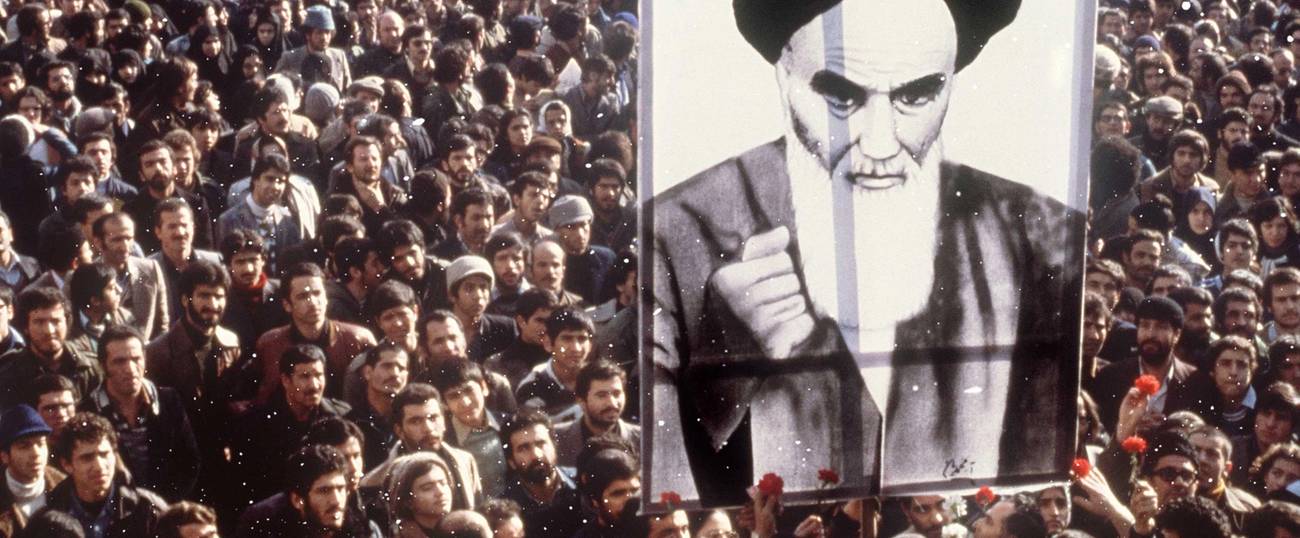

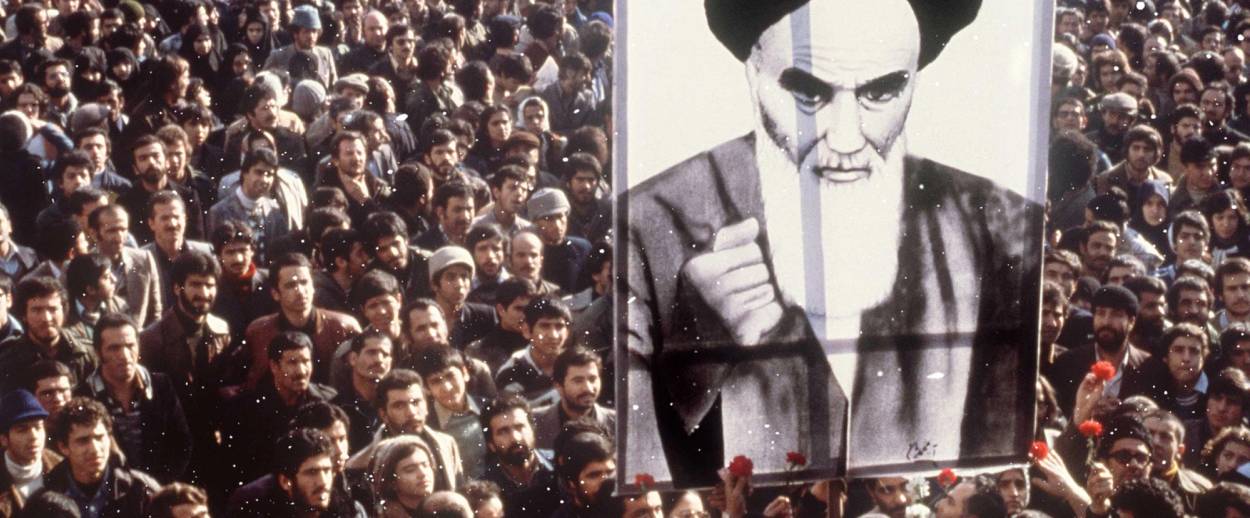

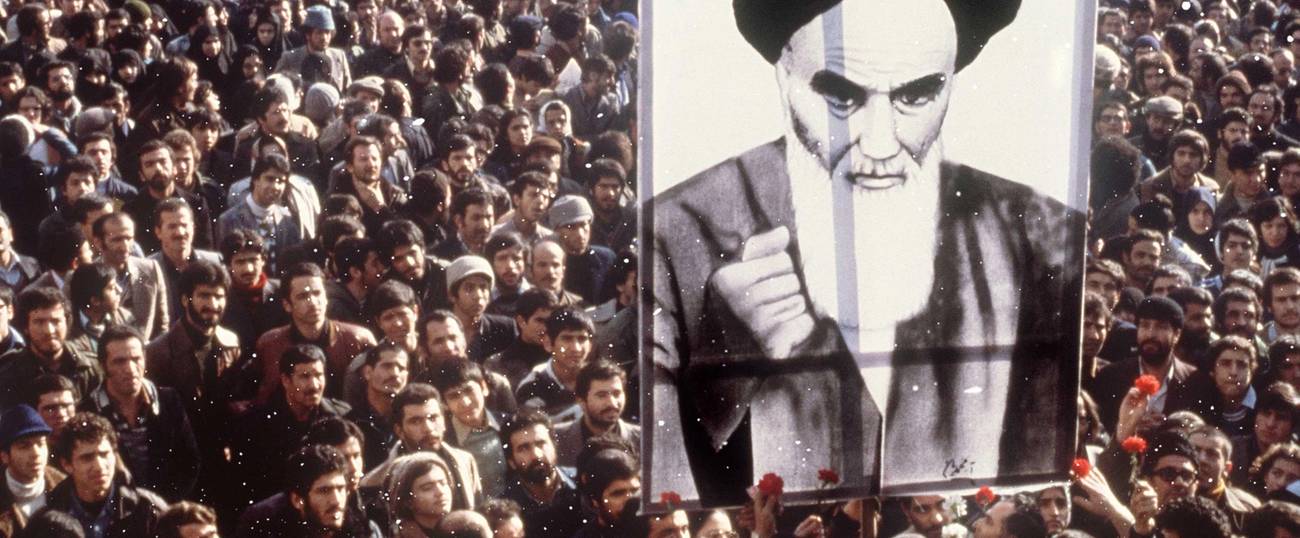

A Retrospective on the Iranian Revolution

Introducing Tablet’s week-long series on the 40th anniversary of the Khomeinist revolution in Iran

This week marks the 40th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution.

On Jan. 16, 1979, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and his family left Iran. Several weeks later, on Feb. 1, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini returned to Tehran from exile in Paris. Within a matter of days the army declared neutrality, the royal regime collapsed, and new regime was established under the principle of velayat-e faqih—governance of the Islamic jurist. Within another year, almost everyone in my family fled the country.

Growing up as the daughter of immigrants—my father was granted asylum in the United States before he gained citizenship—I think I had always thought of the Revolution as a cataclysm, an inexplicable, sudden, violent rupture that divided family stories into Before and After. While the Revolution came up, and it was always mentioned like that, with a capital R, we sort of talked around it, never about the Revolution itself. We knew Khomeini was a villain because my father never mentioned his name without adding some choice expletives in Farsi, but that was it. In the decades immediately following, my grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles were focused on rebuilding their lives, learning new languages, raising children, finding communities. I, however, probably like many children of immigrants, struggled to find a cohesive identity between my Persian self at home, the American kid I was in school and with my friends, and increasingly as I grew older, how either of those identities informed my sense of Jewishness.

It seemed to me that many of my questions came back to the Revolution. In a sense, this series—which I had the privilege of guest-editing—is a personal attempt to probe the legacy of the Islamic Revolution. Most often, the conversation about Iran and the impact of Islamic Revolution is a political discussion: the revolution as a harbinger of political Islam, competitions for regional dominance, the legacy of colonialism and its 20th-century variants. Those are good and important questions, and this series explores some of those issues too.

But while revolutions overturn governments and political entities, they also overturn communities, families, and the lives of individuals. How do people maintain and reconstruct a sense of self when everything that has grounded them for centuries and even millennia has been irrevocably changed?

When 75 percent of the Iranian Jewish community fled, a significant number of Jews decided to stay and they continue to remain there, living and working and practicing as Jews. Roya Hakakian describes the remaining Jewish community as a hopeful elegy, a metaphor for the Iranian people’s striving for freedom. An excerpt from Lior Sternfeld’s excellent, recently released history of 20th-century Jewish life in Iran explores Jewish attitudes toward the Revolution, and how and why some young Iranian Jews participated, as patriots and as Jews. Majid Rafizadeh describes when he first met a Jew in Iran. The Iranian regime is notoriously belligerent toward Israel. Tony Badran writes about the role of the PLO and Yasser Arafat in the Islamic Revolution. How do Jews who left Iran mediate their Persian identity? Novelist Gina Nahai reviews some post-revolutionary memoirs by Persian women. Asher Shasho Levy explores how Persian music reflects the Jewish experience in Iran in an interview with Maureen Nehedar, an Iranian-Israeli paytanit—liturgist. The revolutionary ideology was grounded, in part, in resentment of the West. Thamar Gindin explains the history and lingering legacy of that resentment.

What I have learned is that while in many ways the Revolution was a cataclysm, a violent upheaval, it also was not as much of a rupture as I had always imagined. There is much continuity in culture, sensibility, art, and values, even for those who have left. After all, I, and my siblings and cousins are all still here, thinking about this.

***

Read more about 40 years of the Iranian Revolution in Tablet’s special series this week.

Miriam Levy-Haim is a student at the CUNY Graduate Center’s Master’s program in Middle Eastern Studies, with a particular interest in the history of Jews of the Middle East. She has worked for several Jewish educational institutions developing curricula for adults and teens.