In Israel’s Earliest Days, the Place Its Leaders Felt Compelled To Visit Was Burma

A visit with Than Than Nu, whose father U Nu welcomed Ben-Gurion, Golda Meir, and Moshe Sharett to Rangoon

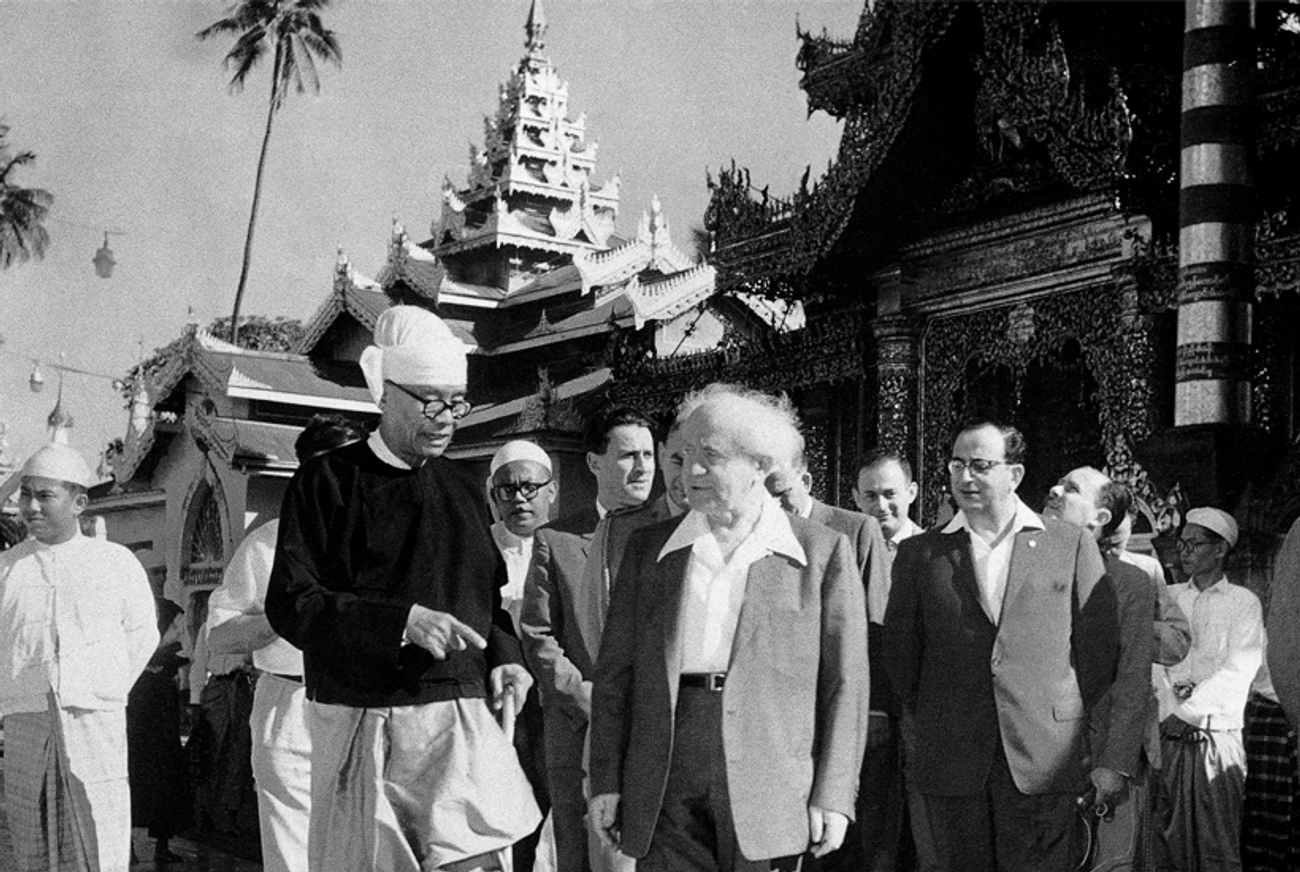

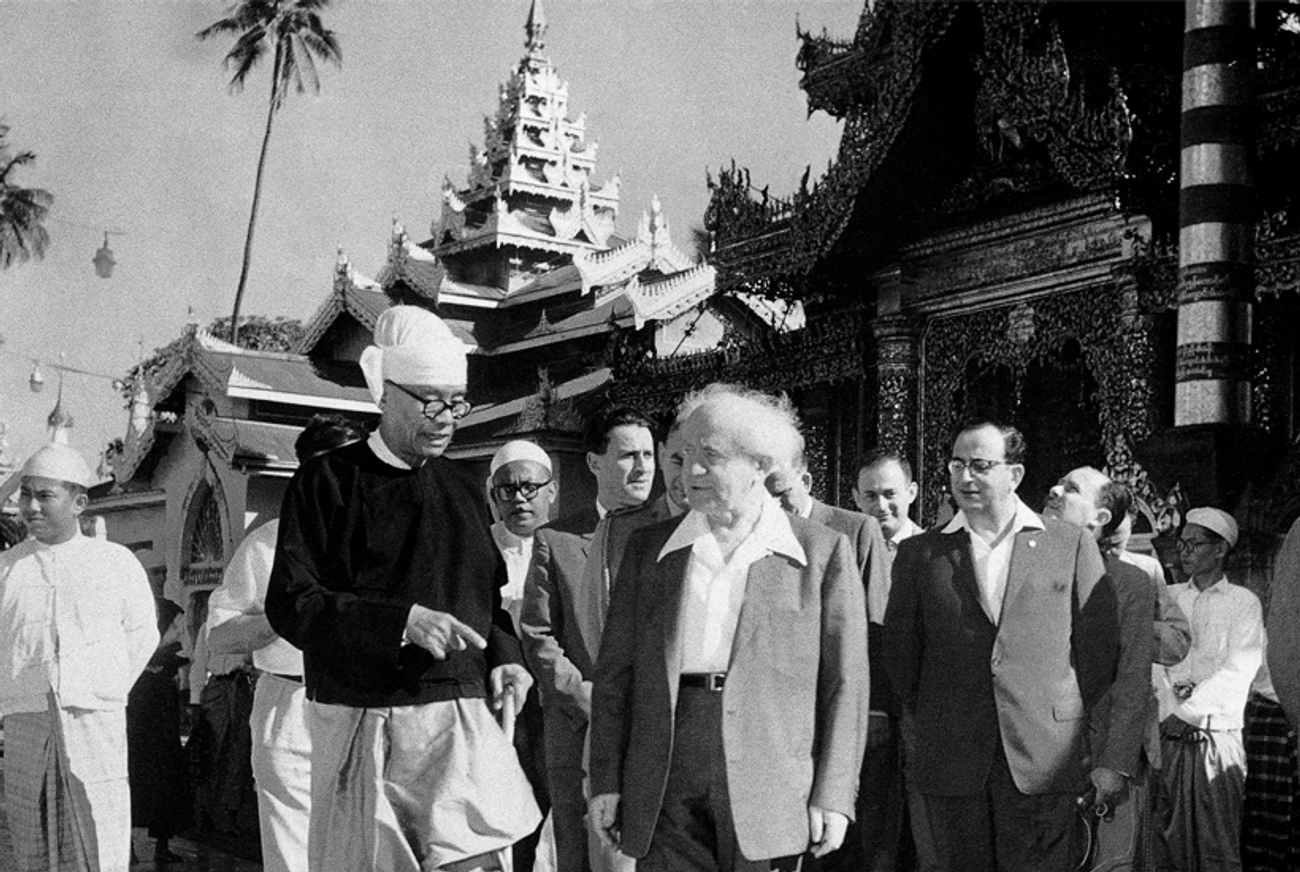

Than Than Nu, the daughter of Burma’s first prime minister, U Nu, works out of a second-floor office on a sun-baked street in Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar, as the country is now known. On a sweltering afternoon last month, a battered taxi dropped me off in front of the entrance. It had been about a year since I first saw black-and-white images of U Nu hobnobbing with Israel’s first leader, David Ben-Gurion, in 1961.

The photos were on display in Yangon’s sole synagogue, where I’d stopped as a tourist during my first trip to the country. Ever since, I’d wondered what Israel’s leaders were doing bumbling around in Burma during the early years of statehood, when there were surely many more crucial alliances to tend to? And why, as I’d read later on the Israeli embassy in Yangon’s website, was U Nu the first foreign prime minister in the world to visit Israel on a state trip? And why has the early blossoming friendship been all but forgotten?

Sammy Samuels, a 33-year-old member of the city’s small Jewish community, told me he thought Than Than Nu could help me understand.

Standing outside the office on Thein Phyu Road, I chugged a small bottle of water, trying to cool off under the shade of a tree. The subdued neighborhood struck me more as an ideal location for convenience stores and little shops, not the headquarters of the Democratic Party (Myanmar), which Than Than Nu started a few years ago. I made my way up a small staircase and was greeted by a room full of chattering people, all preparing for next year’s general elections. I took my shoes off at the door, walked in, and a few moments later was facing a woman with jet black hair wearing glasses, a long-sleeved shirt, and a traditional Burmese longyi. “Hello, I’m Than Than Nu,” she said and invited me to sit in an adjoining room.

At the table with us sat her husband, who remained largely mute during the entire interview, and her octogenarian party chairman, who would chime in every now and then with supporting dates and details, like the fact that Than Than Nu’s brother once lived on a kibbutz. I started off by asking her if what I’ve heard is true—that she’s planning her own trip to Israel. “I very much want to visit, because Israel is a country my father recognized among the world leaders, and another thing is that I heard, especially from my mother, because my mother accompanied him, that Israelis are very hardworking people,” she replied. “They might have some kind of difference among them also, but when the time came for them to protect the country, they were very much united. That’s why Israel is a very strong country.”

I asked what other impressions her mother had shared. She thought for a second, and said her mother told her that the women in Israel were very beautiful.

***

From the start, Israel and Burma had a surprising amount in common. Both countries gained independence in 1948 following British rule, and for both, independence created festering grievances between the new government and those who felt displaced. While the Israelis fought the Palestinians, Burma’s leaders faced ethnic insurgencies that immediately sprang up all over the country, while fighting in China spilled over the border.

In his classic history of Burma, The River of Lost Footsteps, Thant Myint-U writes that U Nu, because of the Holocaust and shared political beliefs with Israel’s labour party, had “a soft spot” for Israel. It’s true that he went out of his way to help his new friends, if a bit awkwardly: In October of 1955, U Nu told Soviet leaders in Moscow that they should let Russian Jews emigrate to Israel. “The Soviet leaders were speechless with surprise,” U Nu wrote in his memoirs, clearly delighting in the role of troublemaker. When the Soviets delicately pointed out that there was an Israeli embassy in Moscow, U Nu replied that Moshe Sharett, who served as Israel’s second prime minister, was “an old friend”—Sharett was one of the first Israelis to come to Burma—and said that helping old friends was an obligation.

That same year, U Nu became the first foreign prime minister to visit the Jewish state, seven years after the founding. Wearing traditional dress, he rode in an open motorcade and waved to onlookers. Today, it’s difficult to revive the importance of his act, but at the time, it was highly significant. U Nu was a major figure among leaders of non-Western countries, many of which had opposed Israel’s establishment. Myint-U writes that in the same year as the historic visit, U Nu attended a conference in Indonesia with India’s Jawaharlal Nehru, Indonesia’s Sukarno, Ghana’s Kwame Nkrumah, Egypt’s Gamal Abdel Nasser, and China’s Chou En-lai—a group not known for enthusiastic support of the Zionist dream.

But over the course of my conversation with his daughter, I understood that U Nu identified with Israel, and Israelis, in a way he didn’t with other young post-colonial states. “I think you know that Israel is the country where all the enemies are surrounding them,” said Than Than Nu, who has never visited Israel herself. “But I think they are also peace-loving people. In Myanmar, we are also peace-loving people and fun-loving people.”

Burma voted in favor of accepting Israel into the United Nations in late 1949. A flurry of visits and diplomatic upgrades followed. In January 1953, Sharett attended the Asian Socialist Congress in Rangoon, as Yangon was then called. That July, David Hacohen was appointed Israel’s minister to Burma—the Jewish state’s first envoy to a country in Asia. Sharett visited again in 1956, prompting the Rangoon Guardian to run a cover story about Sharett headlined “Boy from Russia Who Grew Up to Lead Israel.” Two years later a who’s who of Israel’s founding fathers came through: Moshe Dayan, Shimon Peres, and Israel’s President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. In 1961, Ben-Gurion himself paid his visit, and a year later, Golda Meir traveled to Rangoon.

In his book Israel’s Quest for Recognition and Acceptance in Asia: Garrison State Diplomacy, academic Jacob Abadi writes that the relationship was, in large measure, “a result of U Nu’s conviction that Israel was the quintessential example of the egalitarian social and economic order that he wished to establish.” But the relationship worked both ways. Israel supported Burma with a modest amount of military hardware, such as Spitfire aircraft, expertise, and agricultural training. Several moshav-like settlements were planned for the north of the country. In return, U Nu offered his support in a hostile world—a friend at a time when Israel needed friends.

***

Than Than Nu was a young girl during Ben-Gurion’s 1961 visit, so I asked her if she had any memories of the meeting. “Mr. Ben-Gurion? No,” she replied. “I just remember that he was in this Burmese national dress at the reception, which was given in honor of him at the president’s house.”

The historical stage was set for strange alliances, but as the photos of Ben-Gurion fully outfitted in Burmese costume suggest, personalities mattered too. Ben-Gurion and U Nu clicked, not least because Ben-Gurion evinced an interest in Buddhism. Than Than Nu said the leader of the Jewish state briefly meditated with U Nu, who, despite a hard-drinking adolescence, became a devout Buddhist. Ben-Gurion’s visit was one of his longest trips abroad as prime minister.

After my return from Myanmar, a scholar on Asian Jewry put me in touch with 83-year-old Dr. Moshe Yegar, who served in the Israeli embassy as a junior diplomat during Ben-Gurion’s visit in 1961 and went on to become ambassador to Sweden and the Czech Republic before retiring in 1995. Ben-Gurion, Yegar reminded me in an email exchange from his home in Jerusalem, was a person of great intellectual curiosity. He immersed himself in Baruch Spinoza and the Old Testament. He studied Ancient Greek so he could read Plato in the original. U Nu’s interests also extended beyond politics: The first prime minister of Burma fancied himself a playwright. In his memoirs, he writes self-deprecatingly that his attempts “were not good ones.” “They did not hold one’s interest and were as wearisome as an exchange of views.” Still, he kept at it. U Nu was not a man to give up easily.

While the two only met twice, they corresponded for several years. “It was obvious that they liked each other very much, and enjoyed each other’s company,” Yegar said in an email.

On his flight home in 1961, Ben-Gurion wrote a letter thanking U Nu for his government’s hospitality and for “the personal friendship which binds you and me with ties of love.” He went on. “May you continue to guide your people toward economic, social, and cultural progress. This is your historic mission. Your friend and brother, David Ben-Gurion.”

In Jerusalem, according to Abadi’s history, Ben-Gurion pronounced that the government, and particularly U Nu, “have more loyalty and sympathy to Israel than any other state in the world.” But Gen. Ne Win, who took over in a military coup in 1962, was much less interested in Israeli assistance than U Nu—and cared more about establishing ties with Arab states. Most of the Israeli projects were scaled down or axed, and in 1964 he booted Israel’s experts out of the country.

Yet Yegar, the former junior diplomat, told me that after the military coup, both embassies were kept open and continued to function under a low profile. Nevertheless, over the years of Burma’s military junta, suspicions—most widely explored in a 2000 Jane’s Intelligence Review article—that Israel supported Burmese officials with arms and intelligence training were consistently denied by both governments. (The Israeli ambassador in Yangon did not return repeated requests for comment.)

Than Than Nu remembers when everything veered off course. In 1962, in the days Ne Win took over and her father was jailed, she was about 10 years old. He was released a few years later. They left the country in 1969, Than Than Nu said. That year, U Nu expressed a desire to return to Israel in a letter to Ben-Gurion. “I must again sit at your feet and pick your brains. Your own country needs those brains, but I am sure you are generous enough to spare us a thought or two. In any case it will be a pleasure to listen to you and to provoke you again. With every good wish to you and yours, Your old friend, Maung Nu.” (Maung in front of a name can mean something on the order of younger brother.)

After rallying political support abroad, U Nu returned to Burma in 1980, but never to the same level of influence. Than Than Nu stayed outside of Burma, in India, working in radio, and did not return until 2003. In 2009, she co-founded her political party. Besides her political endeavors, Than Nu serves as a last living link to the honeymoon era. To this day, Israelis visiting the country seek her out.

Besides photos, Than Than Nu has few physical souvenirs of her father’s Israel connection. But then she told me about the watches. “About two years back, I received one very old watch, from one Israeli,” she explained. “Just before he passed away, he gave this watch to his son and said please keep this watch carefully. Because this watch was given to me by U Nu.” It turns out that on his visit to Israel in 1955, U Nu passed out watches to people he met. One of them was a traffic police officer named Aharon Lifshits, whose son Etan arranged for its return to Than Than Nu.

“Is it here?” I asked, a little too excitedly.

“No,” she laughed. “With me, at home.”

“Does the watch still work?”

“If I shake it then it moves a little bit,” she told me, with a knowing smile. “Because it’s a long time back, you know.”

Joe Freeman is a Southeast Asia-based journalist whose work has appeared in The Washington Post, Foreign Policy, The Guardian, The Christian Science Monitor, The Phnom Penh Post, and the Nikkei Asian Review.