For Centuries, Jews Ruled Poland’s Liquor Trade. Why Was That Legacy Forgotten?

Purim reminds us it’s unusual for Jews to indulge in recreational boozing—one reason Polish nobles liked having them run taverns

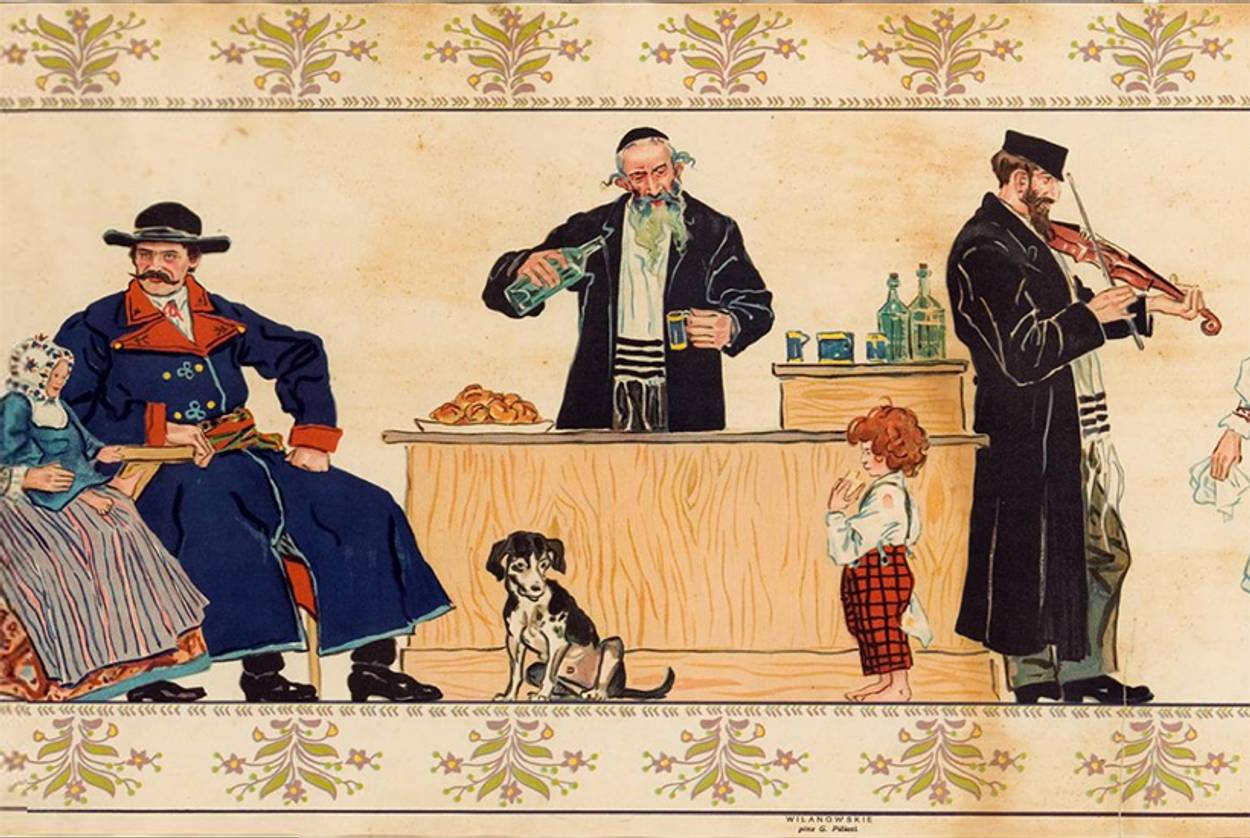

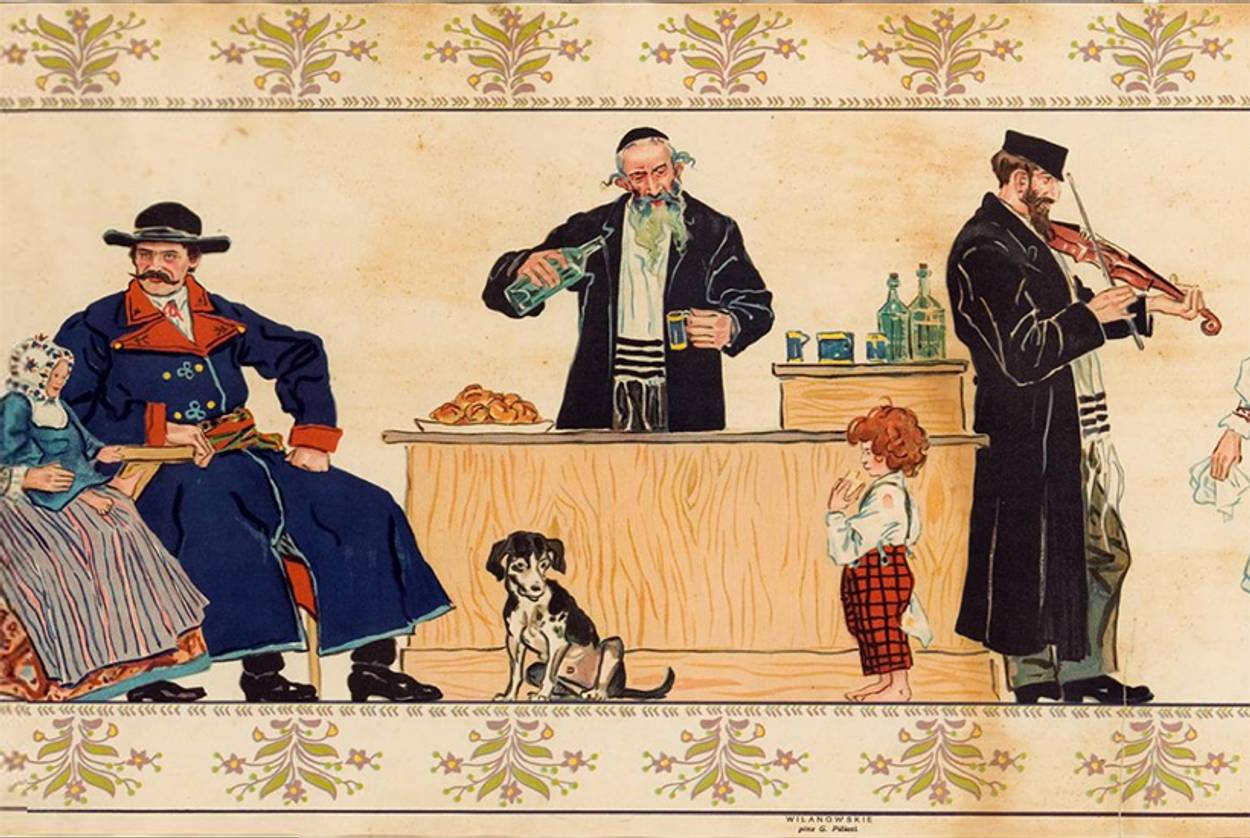

When Polish writer Adam Mickiewicz needed a bar setting for his epic 1834 poem “Pan Tadeusz,” he named his tavernkeeper “Yankel” and described a watering hole that embodied its Jewish owner: “From a distance the rickety old tavern looked / like a Jew rocking in prayer / the roof like a hat, the thatch spilling down like a beard / the sooty walls like a gabardine / in front, carvings protruding like tzitzit down his body.”

Today it seems like a strange idea: Outside of the Nazarian nightclub-and-hotel empire and a few places in the East Village, what Jews own bars? But in early-19th-century Poland, approximately 85 percent of registered taverns were leased by Jews—and there was no shortage of taverns. For Poles of that time, there was a stereotypical image of a bartender, and he had a beard, a yarmulke and peyos. Jewish domination of Poland’s drinking culture was so complete and lasted so long that Poles simply assumed a connection between Jews and booze. As a standard Polish proverb of the time had it: “The peasant drinks at the inn, and the Jew does him in.”

Unlike most other aspects of the collective Jewish experience—in a tradition that commemorates events that happened 5,000 years ago as though they took place last year—almost all traces of this history have vanished from our group memory. Jews entered the field, dominated it in a region, and then left it almost as quickly as they found it. There’s nothing particularly boozy about Jewish economic history or culture, prior to or since this period in Poland. There are no Jewish cocktails and no spirits that are uniquely Jewish. There weren’t any major Jewish innovations in the industry, and the Jewish legacy left to the world of booze is essentially nil. Why?

***

Jews became bartenders in Poland because of a few curiosities of the Polish economy. Chief among them was the system of trade tariffs that raised the cost of exporting Poland’s bountiful grain harvest to the point where landowners couldn’t generate substantial profits selling it abroad. Nobles with land and grain on hand turned to manufacturing—that is, distilling—to turn their product into something worth real money. And Jews, who were usually denied permission to buy land, join artisanal or professional guilds, or pursue higher education, were natural partners: They could provide labor for the distilleries and handle the commercial end of innkeeping.

Indeed, as Glenn Dynner, an expert in Eastern European Jewry who is currently a scholar in residence at the Center for Jewish History, wrote in his recent study of the topic, Yankel’s Tavern, being a tavern-keeper and bartender was about as good as it got for Jews in Poland. He describes it as the era’s equivalent of accounting: an aspirational middle-class occupation, something to which they could apply their skills with a potentially lucrative payoff. As Dynner notes: “They leased taverns because there were not many alternatives for East European Jews.”

And Polish nobles were eager to have Jews run their taverns, largely because of prevalent myths about Jews—chiefly, that they didn’t drink. Dynner provides abundant evidence of what he calls the “myth of Jewish sobriety.” The 19th-century Polish nobleman Antoni Ostrowski described Jews as “always sober,” adding “drunks are rare among Jews.” Indeed, Dynner writes, “Polish folk idioms mocked Jews for having so much much liquor at their disposal yet being so stupid as not to drink it themselves.”

Various writings describe legions of drunken Poles passed out in bars or doubled over fences, while the Jews were busy leeching the Poles of their money and pushing yet more booze on them when they were already drunk and vulnerable to extortion. Later that crystallized into anti-Semitic vitriol. An anecdote from a Catholic priest, written in 1912, speaks volumes about the attitude that the Jewish liquor magnate inspired: “Our small towns and cities are no longer ours, but belong to foreigners. The current municipalities only appear to be in power in small towns and cities; the liquor monopolies hold all the real power. Sober Jews, in a silent economic battle, have foisted intemperance onto us and achieved history.”

Yes, 1912: While many scholars have previously suggested that the Jews’ dominance of the Polish liquor trade concluded in the early 19th century, Dynner marshals evidence showing that the Jews-and-booze trend extended as late as the early 20th century. So, for generations, to have booze in Poland meant to transact with Jews—and, more significant for Jewish culture, to be a Jew in the early modern era was to very likely be associated with the liquor trade. As Dynner noted in an interview, until 100 years ago around three-quarters of the world’s Jews lived in Poland and Lithuania, and as many as 30 percent of Polish Jews were involved in the industry in one way or another.

But then what happened? While Jews in Western Europe enjoyed the fruits of emancipation, their Eastern European counterparts left for Palestine and the United States, where the economic and professional horizons were far broader and the imperatives driving their original involvement in Poland’s liquor trade were totally absent.

Even the Bronfmans, the world’s most famous liquor magnates, couldn’t tie their successes in booze to the legacy of Polish Jewry’s tavern-keeping: They were originally tobacco farmers from Bessarabia. After fleeing the pogroms of Tsarist Russia in 1889 for Saskatchewan, the family’s patriarch Yechiel got a job on the railroad and then another at a sawmill until he and his sons—including Samuel, the eventual builder of the Seagram empire—could get together enough capital to start their own concerns. They sold firewood and seafood and then horses; it was only after buying a hotel and seeing the profits in selling alcohol that the Bronfmans moved into liquor distribution and then happily used their position in Canada during Prohibition to become titans of the industry.

Now there’s not much more than the tradition of drinking Slivovitz—a grain-free alcohol—at Passover to remind anyone of all the drinks Jewish bartenders poured across Poland. It’s of a piece with the overall economic history of the Jewish Diaspora: Through a constant focus on education and skills development, Jews have applied themselves to whatever available field was most advantageous to them. In Poland, that was booze. When they left, they didn’t take it with them.

***

Like this article? Sign up for our Daily Digest to get Tablet Magazine’s new content in your inbox each morning.

Steven I. Weiss is an award-winning journalist and is news anchor & managing editor at The Jewish Channel. His Twitter feed is @steveniweiss.

Steven I. Weiss is an award-winning journalist and is news anchor & managing editor at The Jewish Channel. His Twitter feed is @steveniweiss.