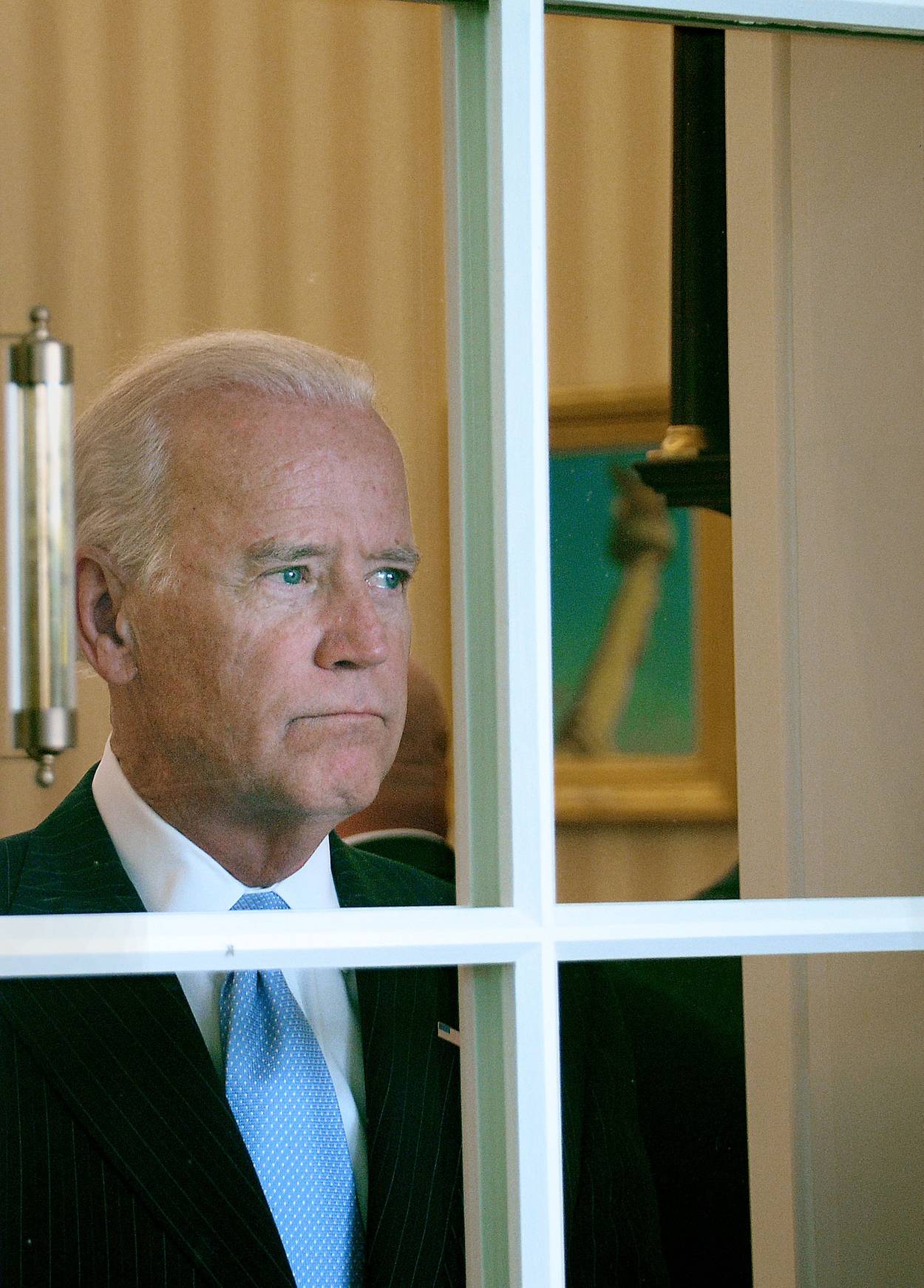

Biden and the ‘Russiagate’ Theorists

Why Joe Biden is the perfect candidate to withstand mad Trumpian conspiracies

Joe Biden’s supreme skill as a candidate consists of an ability to avoid getting hated, which may not seem like much, but which, if you think about it, distinguishes him from the dominating figures of the Democratic Party in recent decades. A normal quota of detractors, rivals, and opponents has always surrounded him, and the normal quota has always done its best to incite a popular loathing, and has fanned the embers, and has tried tossing another match. But nothing has worked. What can account for this? An affable flame-resistant personality, obviously. Also, shrewd analysis, acted upon with extreme discipline, concealed under a cloak of maudlin sentimentality. Genius in the service of geniality is ultimately the explanation.

It is a great achievement. To be unhated in the present atmosphere amounts nearly to a political program. To be unhated is a pitiless condemnation of the party in power. It is a call for social reform in the future. To be unhated is also a crafty maneuver within his own party, the Democrats. It is striking—it ought to be legendary—that Bernie Sanders, having had his head handed to him by Biden in March of this year, made a point of expressing a personal fondness, even so. How many years of careful effort on Vice President Biden’s part must have gone into preparing the grounds for Sen. Sanders’ tone of affection! Hillary Clinton said about Bernie, in regard to the Washington scene, “Nobody likes him,” which may be true. But Bernie evidently felt that, even so, Joe likes him.

The oddities of Biden’s speaking style make their own contribution to the great achievement. The oddities solve an ideological problem. The chasm between separate wings of the Democratic Party is not small, and there are only so many ways of bridging it, oratorically speaking. Bill Clinton’s method was to convince his moderate audiences that he was a moderate, and his progressive audiences that he was a progressive. This was genius of a different sort—though it left behind a suspicion of tricky deception, for which there turned out to be a price, paid by his wife. Barack Obama, for his part, conjures a regal tone that allows him to rise majestically above the low ideological disputes. But Obama’s regal quality is not reproducible.

Biden’s strongest oratorical technique is something else entirely. He knows how to wend his way in the course of a speech to matters of simple patriotic morality, and, having arrived there, to abruptly raise his voice, and raise it still more, until he is shouting at levels that appear to be two or three notches above the appropriate. He resembles Bernie in this respect. He and Bernie are the brotherhood of the left-of-center shouters. Bernie’s shouting remains more or less consistent, however. He starts at high volume and perhaps goes on to add an extra decibel.

But Biden’s shouting comes out of nowhere. It appears to be a volcanic burst, which typically expresses itself as an affirmation of indignant national pride. “This is the United States of America!” he declaims (which you can see in one of the Lincoln Project’s wonderful ads). And, because decibels imply principles, his shouting appears to rebut the progressives’ normal objection to a mere moderate, which is lack of principle.

Here is a problem, though. Oratorical shouting requires a big hall and a large audience, but, under the present circumstances, these things are forbidden to the pandemic nondenial party. Biden will have to draw on other techniques. He does have talents. It was Biden who coined the byword of the Obama-Biden reelection campaign in 2012, “Bin Laden is dead, and General Motors is alive!”—which has got to be the most persuasive political slogan in 240 years of American history. “A battle for the soul of America”—his current slogan—is not at all memorable; is not immortal; will not be recalled in the history books.

It is a brilliant slogan, even so. It goes to the heart of the matter. And the slogan is suited to his affable, sentimental, hate-resistant, public personality. But mostly his oratory will have to be quieter and even conversational, and a lot of it will have to be extemporaneous. Here certain frailties emerge.

Demosthenes, who was the greatest orator of ancient Greece, learned to orate by stuffing his mouth with pebbles, in order to overcome his childhood stammer. Biden appears to have begun the course without ever completing it. Everyone has noticed that, when he is uncomfortable, his syntax sometimes wobbles, and sometimes the sentences decay into fragments. Sometimes he chooses easy phrases that turn out to be wrongly chosen. Even when he is at his best—when he shouts, that is—lonely syllables sometimes float away: “United States America.”

Biden resembles George W. Bush in these respects, even if he has never descended quite as far as Bush into disaster. (Bush managed to say: “Our enemies are innovative and resourceful, and so are we. They never stop thinking about new ways to harm our country and our people, and neither do we.”) Bush never seemed to be troubled by his verbal errors, but that was perhaps because he is a highborn aristocrat, and has never seemed to be troubled by anything at all, not even his wartime failures. But how does Biden keep up his own morale, in the face of his own verbal stumbles? I have no idea. He is said to read Irish poetry, and maybe that gives him strength. If I could whisper in his ear, I would tell him to adopt Bush as his model, on this particular matter. Bush is a humorous man, and he used to joke about mangling his own sentences, which was charming. If Biden stole a few of those self-deprecatory tricks, they might put his listeners at ease, and might make his ridiculers look small.

Biden’s verbal stumblings have an unexpected effect, though, which is to redirect your attention from the sentences to the man. You find yourself reflecting on his life story, which, in his disciplined manner, he relentlessly encourages you to do. You contemplate his political achievements. Perhaps you reflect that Obamacare has the advantage over Medicare for All of having actually been brought into existence. Everybody understands that it was Biden who shepherded the Affordable Care Act through the Senate—Biden who, more than Obama, possessed the ability to struggle one-on-one with the ornery obstructionists. And if the pebbles in his mouth meanwhile lead you to lose the sense of whatever he is saying, why, that is no problem at all. The larger message has already come through.

It is not easy to attack such a man on ideological grounds. The “brains trust” for the Biden administration has already begun to gather; he has laid out a series of big-government proposals; science will be in fashion; taxes for the wealthy will go up. And yet, he appears to be waging a campaign of the spirit—of “soul”—more than of programs, which again is rather clever of him. Trump will attack him as if he were Bernie, of course. But the country has already seen that, in the primaries, Biden was the anti-Bernie. Trump will attack him as a looter and arsonist. But Biden’s instant response to “defund the police” was to announce that he was not, in fact, going to defund the police.

So what else will Trump be able to do to Biden, except revert to form and accuse him of crimes? Only, here, too, Biden will turn out to be well fortified. Even if Trump did come up with something bad looking to say about Ukraine, by now nobody will believe him. As for China, it is Trump, of course, who has turned out to be Xi Jinping’s patsy—not in regard to everything, but crucially in regard to the pandemic. No one can be surprised at the Bloomberg News report to the effect that Trump is China’s preferred candidate—Trump because he weakens the American alliances, which strengthens China in the long run, even if he also rails at China and goes about his trade war. Putin’s support for Trump reflects, of course, the same analysis.

Then again, Trump is not entirely serious about the trade war with China, given that, as John Bolton tells us, he offered Xi a break in exchange for political favors. And there is Bolton’s revelation that, in private, Trump encouraged Xi to put Muslims in concentration camps, which may be the single most dreadful thing that Trump has ever done. None of this will prevent Trump from pretending to be Xi’s principled antagonist, even so, and from accusing Biden of Chinese corruptions. But the power went out of these punches long ago.

And so, Trump will return—he will have to return—to the grand conspiracy theory about Robert Mueller and the impeachment. This is the “Russiagate” theory, about the Deep State and the plot to stage a coup against the president by making up accusations about Russia, which led to the impeachment “hoax” and the accusations about Ukraine. It was never clear in the original version of the “Russiagate” theory why the FBI would have wanted to stage a coup. And why would Obama have wanted to turn against the whole of American political tradition by taking part in such a plot? The “Russiagate” theory always seemed a little thin in those ways. But lately the theory has thickened, and motives for the conspirators have been proposed. In Obama’s case, he is said to have plotted against Trump in order to protect the Iran deal. And Biden has been enlisted into the expanded theory. Biden, in this line of argument, has descended into senility, and his candidacy is a Trojan horse to bring Obama back into power in order to achieve the secret goal, which is the protection not just of the Iran deal, but of the Islamic Republic of Iran itself. Here, then, is the Trump campaign.

Only, why would Obama want to protect the Islamic Republic? And why has Obama plotted in particular against Gen. Mike Flynn, the earliest of Trump’s four national security advisers? In the “Russiagate” theory, Flynn, far from being the appalling figure of political corruption and uncertain national loyalties that he appears to be, is a decent, patriotic, and heroic American, who was driven by the sinister conspiracy into lying to the FBI. Or else Flynn did not lie to the FBI, but, instead, was driven into lying to the court about having lied to the FBI. Various tangled arguments have been offered to explain why these contentions in Flynn’s defense are not as ridiculous as they seem—though anyone who is tempted by the tangled arguments might want to look at the commentaries of Barbara McQuade, formerly a United States attorney in Michigan, in the law blogs Lawfare and Just Security and in USA Today, where she disentangles the tanglements. But the “Russiagate” conspiracy theory also touches on a further absurdity that not even McQuade addresses.

This is the motive attributed to Obama, which, as always in conspiracy theories, is hinted at, or insinuated, or whispered, but is never stated openly. Or the motive is said to be a mystery, which makes it excitingly unknowable. In Obama’s case, though, everyone who has ingested the conspiracy theories of Donald Trump over the years understands that no mysteries inhere to the mystery, and everything is known. For Barack Obama is not an American. And doesn’t everyone know that Obama, the non-American, is secretly a Muslim? Obama’s motives are treasonous by definition. Obama is determined to bring about the destruction of the Jewish state. He is keen on damaging America because he is faithful to the Muslim plan for world domination. And, in taking over the senile Biden’s hapless campaign, Obama has shown a sinister commitment to persisting in his diabolical plan.

Trump conjures the accusation when he attaches the word “traitor” to Obama, as he has lately done. Trump’s supporters embellish the accusation by making “Russiagate” appear to be soundly based on a reading of official documents. And, in this fashion, the “Russiagate” theory, in order to include Biden, has blossomed into a renewed version of the birther madness, all of which adds up to “Obamagate,” in Trump’s phrase. Hillary’s emails are bound to make an appearance in this theory, too, if they have not already done so, together perhaps with Joe Scarborough’s murder victim.

I wish I could say that no one, apart from the crowds at Trump rallies, could possibly be influenced by this sort of thing. But, on the contrary, I notice that, here and there in the respectable press, occasional revelations about minor procedural errors at the FBI set off bouts of panic, and the finest of journalists end up invoking the word “Russiagate,” quite as if a sinister plot against the president did somehow exist. The intelligent writers who carelessly indulge the “Russiagate” word normally do not mean to invoke the whole preposterous theory—and yet, they run into the problem that, regardless of how many times the FBI may have stumbled or overreached, “Russiagate” theory makes no sense unless the people who are said to be anti-Trump conspirators can be assigned a plausible motive.

So Obama’s name comes up willy-nilly, and the wilder reaches of the already wild “Russiagate” theory sooner or later heave into view. This has happened from time to time even among my esteemed colleagues at Tablet, with the requisite hint about the mystery-that-is-not-a-mystery of Obama’s intentions. It is puzzling. It is dismaying. A conspiracy theory virus seems to me at work, on top of the coronavirus. Or it may be that Trump has figured something out, which is that, in modern America, people find these kinds of theories irresistible.

Trump will stick with “Russiagate,” then, in order to go after Biden. And the 2020 election will wander down a different mountain path than the midterm election in 2018. Trump framed the midterms as a referendum on nativist hatreds for immigrants, as I pointed out at the time—which went pretty well for him and the Republicans in the Senate races, though it went badly for them in the House races. But Trump will turn this year’s election at least partly into a referendum on mad conspiracy theories, in conjunction with crowd-pleasing moments of “Kung Flu” Chinese-bashing, the salutes to the Confederacy, and the frightening invocations of the fascist antifas, the looters, the rapists, and the schoolteachers. How will it go, this time? The president’s supporters will find it very exciting.

But Biden seems almost to have anticipated this sort of thing. Conspiracy theories proved to be effective against Hillary Clinton because the Clintons were too canny for their own good, which has allowed a portion of the public to attribute to them diabolical traits. Conspiracy theories have likewise had some success against Obama, in his case because he is Black, and has a funny name, to boot, which has allowed some people within that same portion of the public to regard him as suspiciously remote from themselves, therefore as exotic, therefore potentially demonic. Or the conspiracy theories have now and then had a success because clumsy or foolish American foreign policies have sometimes aroused an hysteria among Israel’s friends, and hysteria lends itself to paranoid conjectures, e.g., about Obama and Islam.

Biden, though, has very intelligently spent the last half century presenting himself as Mr. Next Door from Scranton, Pennsylvania, reliably Catholic, reliably ordinary, and reliably lacking in mystery. Whatever Trump has figured out, Biden appears to have figured out, as well, and how to armor himself against it. Suspicions and hysterias fly in Biden’s direction, and bounce off his helmet. So the campaign is on. But, as a result, a main accusation that will animate the Republican effort, the accusation that Joe Biden is a tool of an alien crypto-Afro-Muslim conspiracy to destroy the American way of life on behalf of the Islamic Republic of Iran—this accusation is destined to seem, well, a bit much. For, say what you will, the man is hard to detest.

Or so I tell myself, in these sultry, ominous, disease-ridden, early summer days.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.