Kiev Begins Weeklong Memorial To Mark 75 Years Since Babi Yar Massacre

Numerous Ukrainian Jewish figures gave impassioned speeches in Ukraine’s parliament, including Israeli President Reuven Rivlin

On September 29, 1941, the Nazis carried out a massacre by bullets against almost 34,000 Jewish men, women, and children at the Babi Yar ravine outside of Kiev. Under the shadow of Ukraine’s continued conflict with Russia, the government of President Petro Poroshenko has embarked on the most comprehensive and committed memorializing of the events in the history of the Ukrainian state. This year’s 75th anniversary commemorations of the Babi Yar massacre have felt like one of the most important in the history of the Ukrainian statehood—a sentiment that has been reflected in a number of ceremonial speeches, and echoes here on the streets of Kiev.

The entire Babi Yar location has been refurbished and renovated and a new memorial to the Roma has been erected as of last week. The Canada based organization Ukrainian-Jewish Encounter, who have for several years been doing excellent work on fostering cooperation and dialogue on both the political and academic levels between Ukrainians and Jews, organized the lion’s share of the commemorative events. A week of events was inaugurated by a youth conference here in Kiev, and the German, Austrian, and Ukrainian governments all had their own programs, too. In fact, this year’s events have been so extensive that attending all of the various conferences, symposia, memorial gatherings, exhibitions, concerts, and dinners (I was informed of at least 35 events) would prove impossible for any individual, even if they somehow managed to procure invites and speedy transportation to the most high profile events.

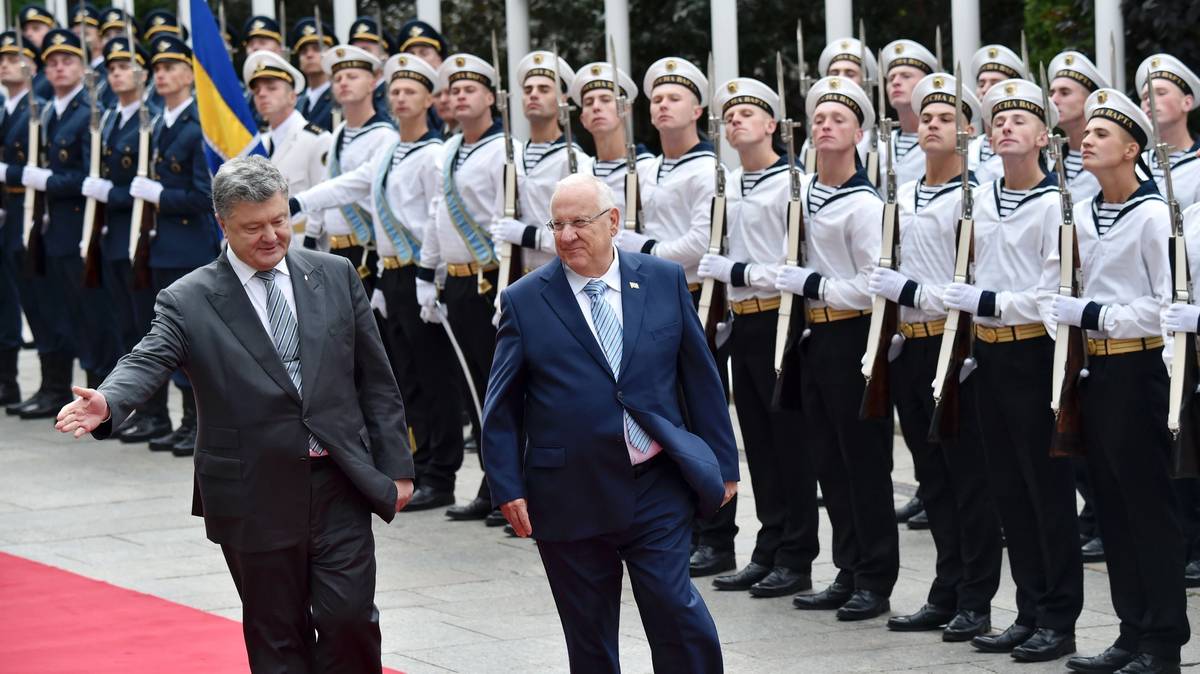

Israeli president Reuven Rivlin arrived in Kiev for an official state visit. With Israel’s head of state visiting, the Israeli national flag flew over government building and across the length of the central Khreshchatyk Boulevard. On Tuesday afternoon, Ukraine’s parliament, the Verkhovna Rada, held three hours of hearings on the events of Babi Yar, which were attended by dozens of MPs, dignitaries, and the patriarch of the Ukrainian orthodox church. The hearings consisted of short parliamentary style several minute long speeches given by various MPs and political dignitaries. Volodymyr Viatrovych, the controversial head of the government-funded Ukrainian Institute of National Memory, spoke, as did Ukraine’s Brooklyn-born chief rabbi Yaakoc Dov Bleich. After the speeches, he informed me that it was the first time that the chief rabbi of Ukraine had ever spoken on the floor of the Ukrainian parliament. Also noteworthy was Rabbi Moshe Reuven Azman, of Kiev’s Brodski Synagogue, blowing the shofar on the podium, likewise a first on the floor of the Verkhovna Rada.

Jewish Ukrainian Parliamentarian Georgy Logvinsky, a member of the People’s Will party who was one of the prime organizers of the hearings, gave an impassioned speech about the coexistence of the Jews and Ukrainians. He switched into Hebrew at the conclusion of his comments. Somewhat incongruously, but with doubtless noble intentions, the screens of the parliamentary assembly began playing excerpts from Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List as well as piping in John Williams’s stirring theme during Logvinsky’s speech. As Logvinsky concluded his speech to the crescendo of Schindler’s List, an older Roma woman sitting next to me began weeping into her purple shawl.

Though he did not speak himself in parliament, President Poroshenko attended in person to listen to president Rivlin’s remarks after the two heads of state appeared jointly in the presidential administration building across the street from the parliament. Rivlin’s remarks to parliament were forceful, balanced, and respectful—he noted that Ukraine and Israel had a great economic and political future together—but they ended on a critical note. The president related the story of his own Ukrainian roots and spoke of his own family history, while condemning the kind of double erasure that befell the victims of Babi Yar. Those who were killed we could never get back, he noted, but they were in effect doubly erased from history because we would never know their names. There were many collaborators among the occupied Ukrainians, themselves victims of the Nazi regime, but there were also at least 2,500 who had been recognized as righteous of the nations by Yad Vashem. Rivlin added that the relationship between Jews and Ukrainians was excellent, and looked to the future, but noted that we could not forget the past. Rivlin concluded his comments with a warning to Ukrainians about not making heroes of complex historical figures such as members of the OUN.

The final and most important of the commemorations are slated for Thursday, with a massive state event at Babi Yar, which is set to be attended by 1,600 dignitaries and at least half a dozen heads of state.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.