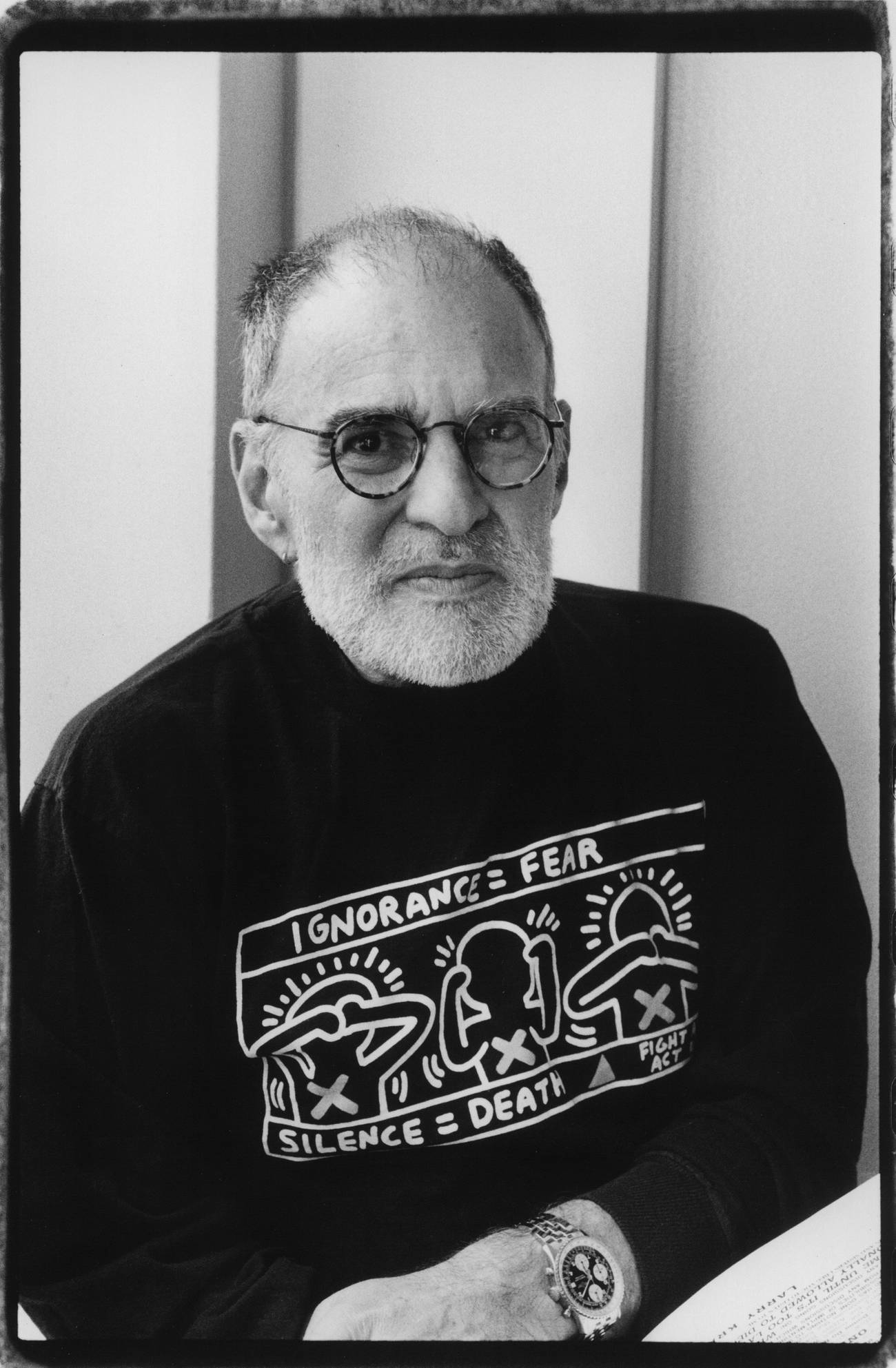

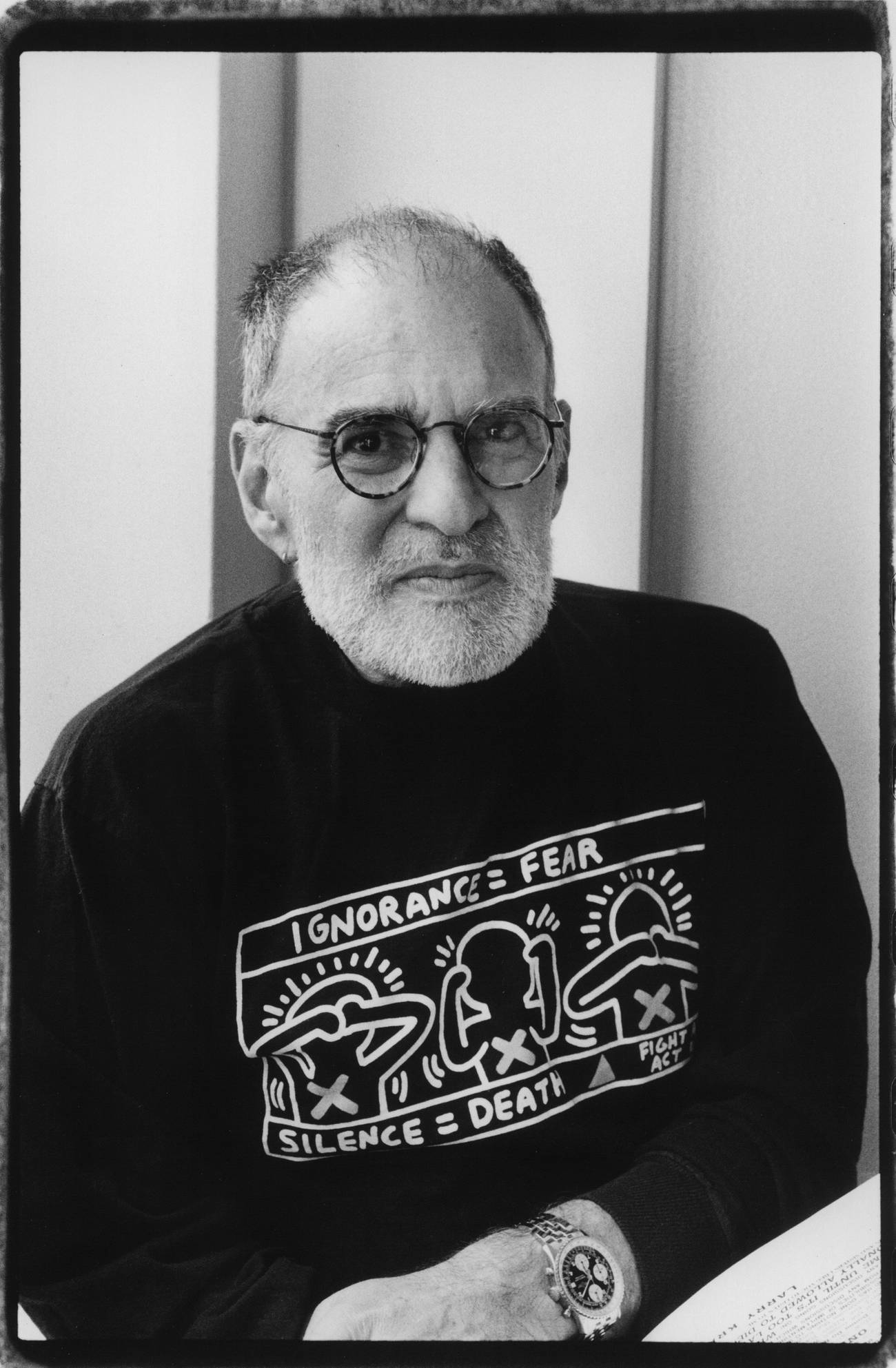

Larry Kramer

The late playwright and AIDS activist saw enemies everywhere—and he wasn’t wrong about that

There is a poignant irony in the death of Larry Kramer amid the ravages of a global plague. One of the most consequential social activists of the second half of the 20th century, Kramer, who died last week of pneumonia at the age of 84, made his mark as the Cassandra of HIV/AIDS. Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC), the very first organization dedicated to fighting what was then a mysterious disease killing mostly young, healthy homosexual men, was founded in his Greenwich Village apartment in 1982. “1,112 and Counting,” his clarion call in the New York Native to “scare the shit out of” its readers, still sends shivers almost four decades later. ACT UP, the direct action group that shut down the New York Stock Exchange and disrupted mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral with condom-throwing antics, was kicked off with a fiery Kramer speech in 1987.

Kramer’s literary output paralleled his activism. His picaresque 1978 novel, Faggots, an indictment of the hedonism and promiscuity that characterized much of urban gay life in the years after the Stonewall uprising, was intended as an endorsement of love and commitment over fleeting, anonymous sexual encounters. But its lurid descriptions of gay sex repulsed many straight critics and outraged gay ones. “Revolting,” declared The Washington Post, while the Los Angeles Times predicted it would elicit “only loathing and contempt” from mainstream society. The reaction was even more virulent from fellow gays, many of whom saw a puritanical zealot eager to shove them all back into the closet. Kramer’s best friend stopped talking to him and the bar owners on Fire Island, where he summered, refused him entry to their establishments. “I had somehow given our secrets away,” Kramer once explained to me about the reception to Faggots. “I couldn’t believe it.”

When a sexually transmitted disease began taking the lives of so many of those men just a few years later, Kramer’s fictitious work began to look horribly prescient. The early years of the AIDS epidemic inspired his greatest artistic achievement, The Normal Heart, a theatrical roman à clef about the founding of GMHC and its battle against governmental, media, and societal indifference. In all of these works—fictional, factual, or somewhere in between—Kramer assumed the role of an Old Testament prophet, an entirely fitting persona for this adamantly secular but irrepressibly Jewish soul.

While Kramer is rightly being remembered for his work as an activist and playwright, overlooked in the obituaries and tributes pouring forth was his role as an amateur historian. Like much else about him, Kramer’s record here was messy and imperfect, but driven by the purest motives.

Closeted and friendless as a Yale freshman in the fall of 1953, Kramer tried to kill himself by overdosing on pills. Years later, after he had come to terms with his sexual orientation, he decided that he would one day do something “to make it easier for gay kids so that nobody would have to go through what I went through.” A student of American history, he envisaged an academic program, likened to the African American and women’s studies departments then percolating on campuses across the nation, devoted to the “exploration of and reclaiming of gay people’s history since the beginning of America.”

In 2001, after several, tempestuous years of negotiation (nothing involving Kramer was not tempestuous) the Larry Kramer Initiative for Lesbian and Gay Studies (LKI) was founded with a $1 million grant from his older brother Arthur. The program was ambitious, but it faced severe challenges in the form of a Yale administration skeptical of its academic rigor and academics seemingly determined to confirm that skepticism, as evidenced by a two-day conference the initiative hosted in 2004 titled, “Regarding Michael Jackson: Performing Racial, Gender, and Sexual Difference Center Stage.” This, just a few months before Jackson was tried on child sex abuse charges.

A student at Yale at the time, I wrote a column for the Yale Daily News criticizing the conference and the overall direction of the initiative. Inviting scholars from all over the country to convene at Yale for a symposium that seemed to conflate America’s most infamous pedophile with homosexuality, I suggested, was not the best use of Arthur Kramer’s largesse. Larry Kramer got in touch to tell me he agreed, that he was heartbroken over the direction his namesake initiative had taken by prioritizing abstruse gender theory over nuts and bolts historical inquiry. “Gay people have no history of note, history that can change our place in society and give us a heritage, a place in the world, and one, for the most part, to be proud of,” he wrote in an anguished letter to the Yale Daily News. The following spring, I chose Kramer as my subject for a biographical writing class. There I was, a brash, inexperienced, know-it-all; Kramer, a brash, battle-scarred, hell-raiser. But we bonded over a shared concern—the sidelining of legitimate gay history in favor of faddish “queer theory”—and developed an unlikely friendship as a result.

Kramer’s fondness for profanity was jarring at first. It took some getting used to seeing this small and soft-spoken man, decked out in a conspicuously large amount of turquoise, interjecting a dirty word whenever he felt the need for added effect. I was used to hearing myself and my friends speak in this “fuck patois,” as Tom Wolfe called it, but certainly not a distinguished playwright. “It’s just sort of the way he operates,” Calvin Trillin, a fellow member of the Yale class of 1957, once told me about Kramer. “By starting out to clear the battlefield with some blast of grapeshot.”

This was Kramer’s M.O. in everything he did. Gays had been rendered invisible by mainstream society and if it took some shouting and name-calling (OK, a lot) then who the fuck were you to complain?

Many people, probably numbering into the thousands, had the wrath of Kramer visited upon them. Ronald Reagan. Yale administrators. His fellow gay men. Random passersby on the street. And don’t get him started on Barbra Streisand.

Just ask Anthony Fauci. In 1987, Kramer claimed that Fauci—then, as now, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases—was a closeted homosexual and that his wife, an AIDS nurse, “looks like a lesbian.” When Fauci told Kramer that, while he could handle the criticism, the attack on his wife “was out of bounds,” Kramer apologized profusely and said that the lesbian comparison was intended as a compliment. This was the typical experience for people who got to know Kramer. He would insult you one moment, and then be all warm and fuzzy the next.

The centering of the gay experience in American history was the lodestar of everything Kramer did.

That’s what he was trying to accomplish, however shambolically, in his mammoth novel The American People, the second volume of which was released in January just a few months before he died. Critics alleged, not inaccurately, that Kramer often saw homosexuality where it did not exist. Sometimes (well, often) his imagination got ahead of him, like when he claimed that Abraham Lincoln was “unequivocally gay.” (The verdict on that one is still out, so to speak.)

But if Kramer’s aim was occasionally off, his goal was true. The role of gay people, and homosexuality more broadly, in the history of the United States has not been afforded the status it deserves, either in schools, publishing or popular culture. “Most historians taken seriously are always straight,” he complained to The New York Times earlier this year. “They wouldn’t know a gay person if they took him to lunch.” Kramer was an insistent advocate of the notion that gays “are not crumbs,” that their stories deserved to be a part of the American canon as much as any other minority group. He confronted the world as a minority twice over, and while he was not a religious man, (indeed, one might even say he was irreligious), he was deeply shaped by the postwar Jewish American experience. For Kramer, the Nazi extermination of the Jews provided a template for understanding the AIDS epidemic and mainstream society’s fear and loathing of gay people. “You can march off now to the gas chambers,” he admonished gay men who did not heed his calls about safe sex. Ronald Reagan was “Adolf Reagan.” A collection of his writings was titled Reports from the Holocaust. I remember once traveling with Kramer on the Metro-North to his home in Connecticut as he toted a copy of the just-published Buried by the Times, a critique of The New York Times’ coverage, or lack thereof, of the Holocaust.

Many would call such comparisons irresponsible, and, to my mind, equating governmental indifference to an epidemic with a premeditated campaign of mass extermination is indeed hyperbolic. But for a gay man living through the AIDS crisis, attending funerals every weekend (if not more frequently) and surrounded by a society best described as apathetic to your suffering: To what else could one compare such a torment?

“I feel I have lived,” Kramer once told me, sprawled along a couch in the Greenwich Village apartment where, 23 years earlier, he decided to do something about the disease that was killing his friends. “Even if I should go tomorrow; I feel that I have been well used.” Kramer was indeed well used. And through his insistence that other gay lives are worth studying, remembering, and just considering, he not only broadened our understanding of American history. He assured himself a place within it.

James Kirchick is a Tablet columnist and the author of Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington (Henry Holt, 2022). He tweets @jkirchick.