It’s the Liberalism, Stupid

To fix what’s wrong with America, we should first understand its defining civic faith

What exactly is wrong with America, and how do we fix it?

That, with slight variations, is the question constantly nipping at our heels these days, asked by friends and colleagues, entertained at dinner parties, floated around on podcasts and in opinion pages. Analyses of what precisely is broken vary, as do prescriptions for a cure, but a strong consensus remains solid among our best and brightest—the problem is that liberalism has come under attack, and the solution is to restore it to its old glory.

In this telling, the history of the past 30 or so years in America goes something like this: Once upon a time, back in the halcyon days of the 1990s, America was great, because Americans all observed a shared creed called liberalism. This relaxed civil religion nurtured our individual liberties and kept us honest, hardworking, and good. It gave us civil rights and gay marriage, Tom Hanks and Sesame Street, bipartisanship and Teach for America. And it would have bloomed eternal if the barbarians hadn’t shown up one day to sack our glittering Rome.

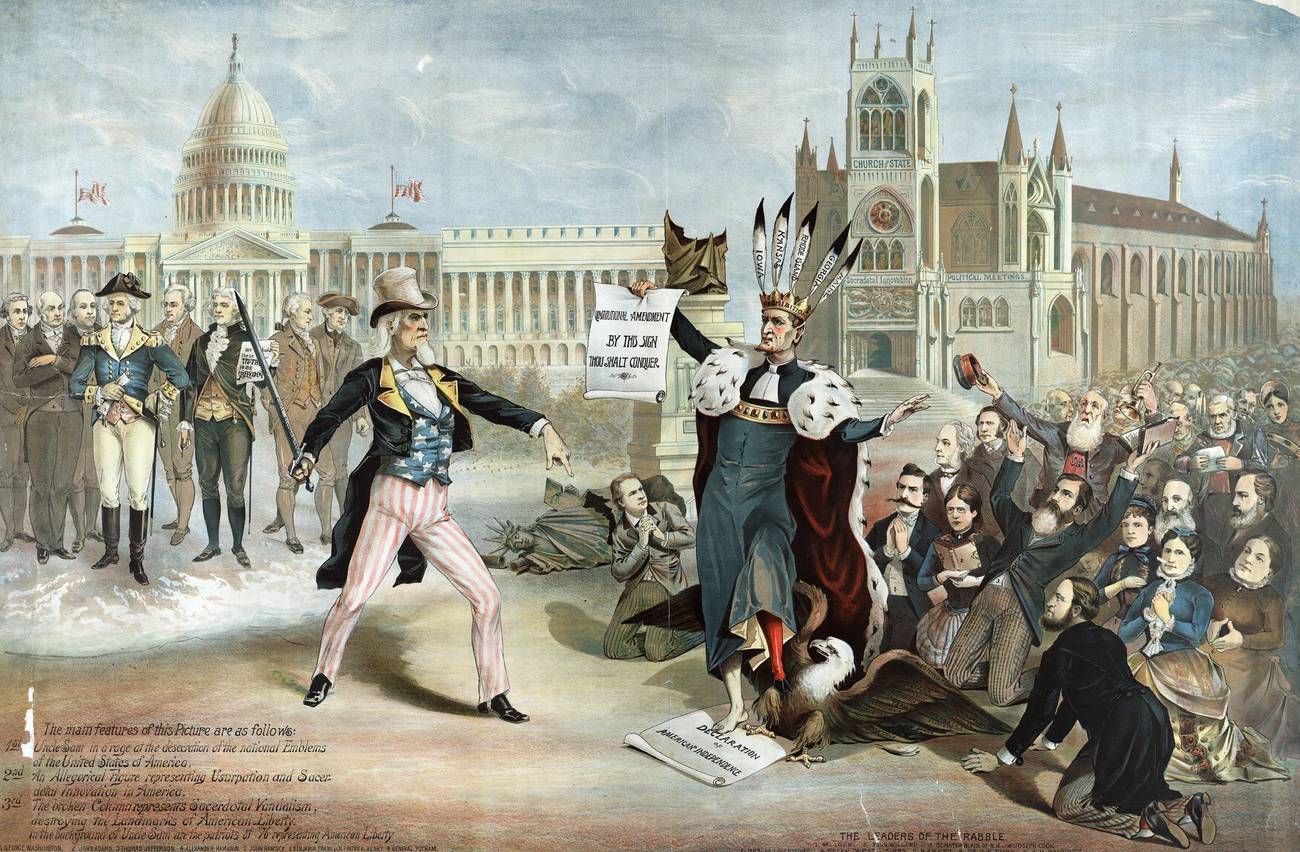

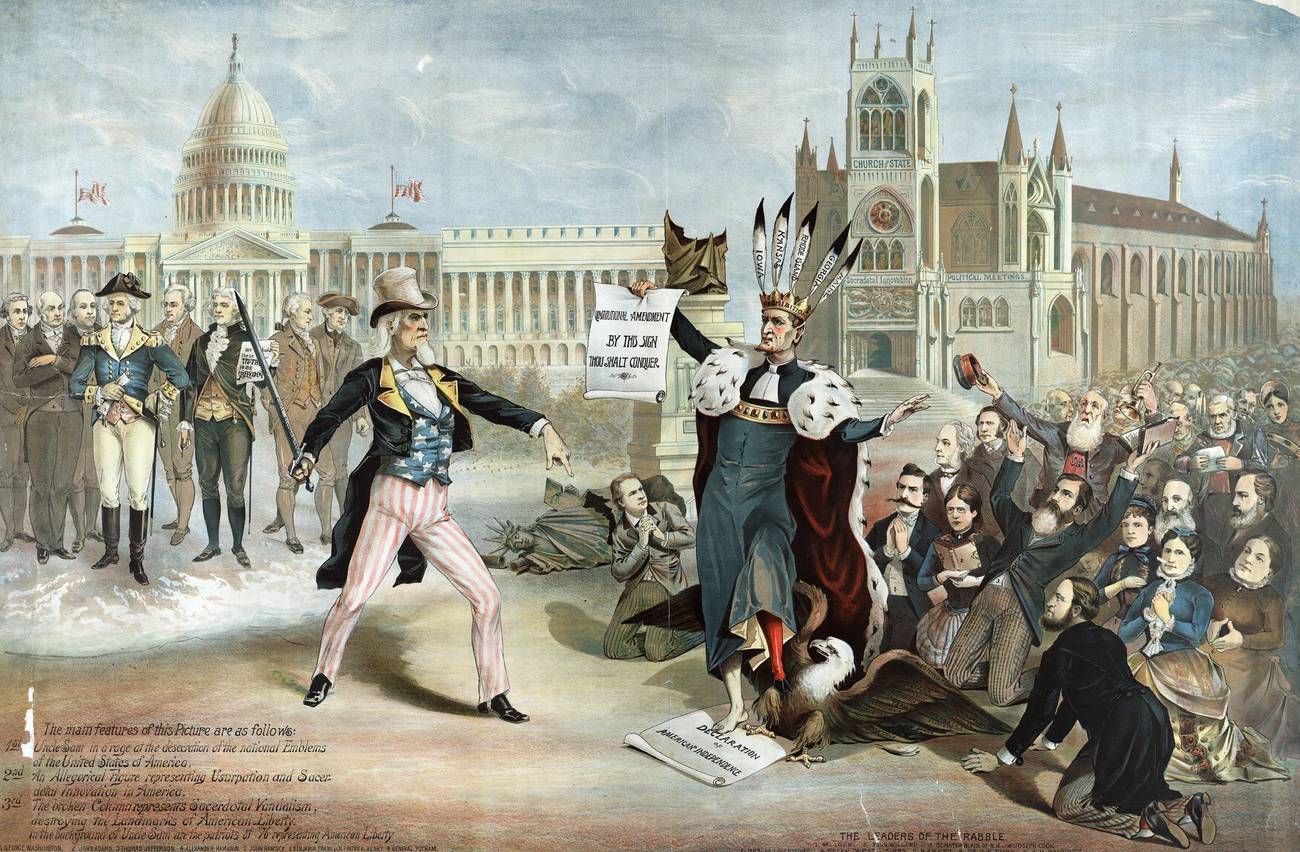

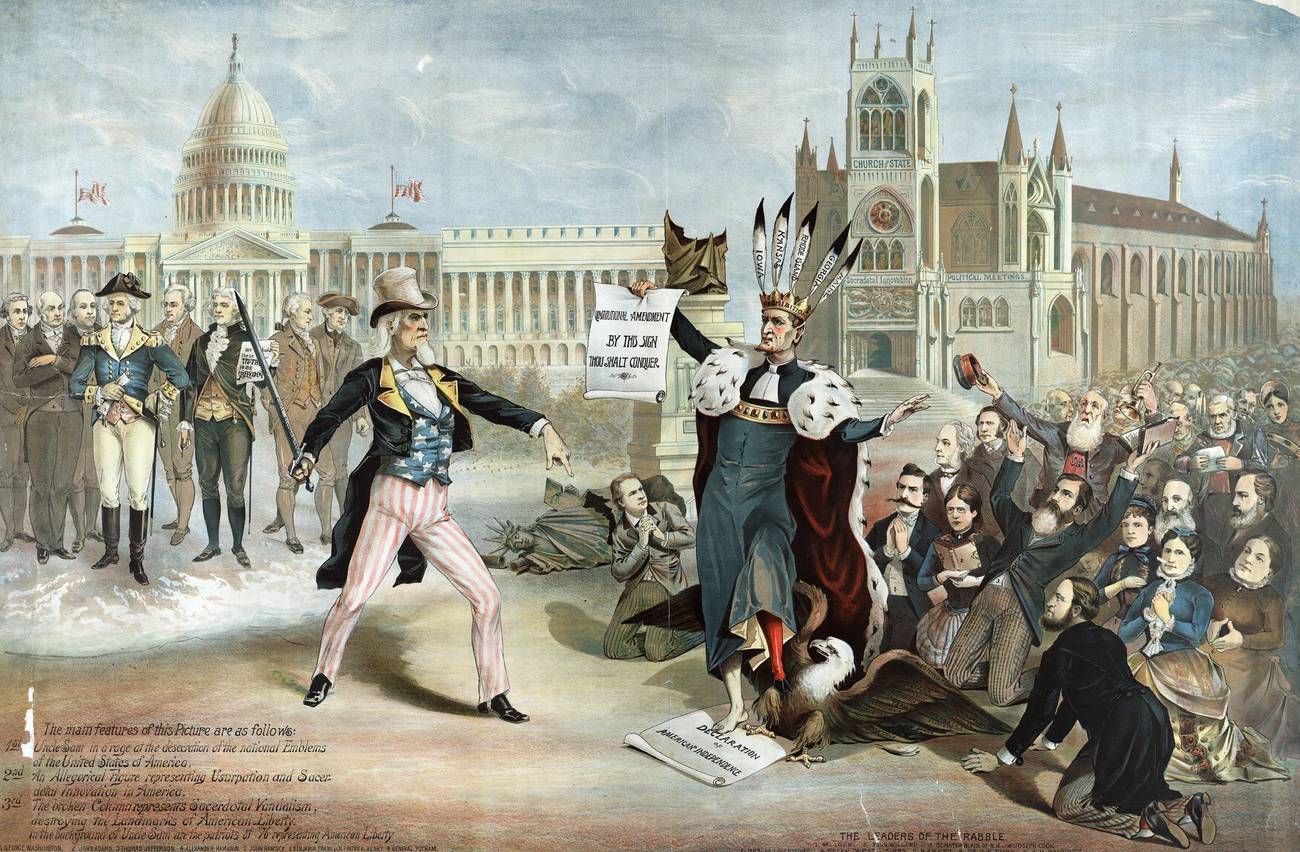

Who, exactly, are those modern-day wreckers of civilization? Again, many of our intellectual betters are certain they have the answer: The barbarians are Marxists, extreme leftist agitators here to replace our sacred liberal order with a pagan religion of their own, complete with a set of rituals (taking a knee) and articles of faith (gender is fluid). Our mission, therefore, is to resist these savages at every turn, and do whatever we can to turn the clock back and reinstall liberalism as our exclusive and infallible operating system.

It’s a compelling story, complete with deliciously malicious bad guys and wonderfully virtuous sheriffs counting the minutes to High Noon. It’s also, alas, entirely wrong. Liberalism, to keep with the Hollywood imagery, isn’t the damsel in distress, hogtied and left on the train tracks; it’s the mustache-twirling villain whom we must defeat if we are to survive.

Take a moment and read that last sentence again. If you were raised in America and attended any school here in the last, say, 50 years, this sentence—liberalism is the source of our woes—makes about as much sense as saying that Mr. Rogers is a sadistic serial killer, or that bald eagles ought to be shot on sight. It sounds not only sacrilegious but outright stupid, a proposition so far-fetched and so far removed from everything we understand to be at America’s core as to merit not a second more of consideration.

In large part, that’s because we, as a poet who was no great fan of the Jews once neatly put it, measure time in coffee spoons. We arrive into this world screaming, and understand before too long that what separates us from other living things around us is the unshakable awareness of our own mortality. This, in turn, puts us into a fraught relationship with time itself, our great nonrenewable resource, which explains why our language is thick with expressions like “time is money” or “a stitch in time saves nine,” which comically betray how poorly we understand the essence of the torrent against which we all futilely swim. To us, 50 years is a long time; 350 years a virtual eternity. Go tell that to a mountain, say, and if you listen carefully, you’ll hear a soft, stony snicker.

And so, because we treat time in this particular and charmingly solipsistic way, we believe that the history of the last few centuries, a period we sometimes call the Enlightenment, is not so much history as human destiny. We cannot imagine the Enlightenment as an era, and are even less capable of contemplating it coming to an end—for if it does, what’s to become of the many bounties it bequeathed us, from stable democracies to lifesaving science?

These are fair reservations, but as we attempt to stumble back and see the liberal order’s virtues, let us catch a glimpse of its vices as well. The world into which Rousseau and the other founding fathers of the Enlightenment emerged was one governed by a simple philosophical proposition, cultivated for centuries by religions of all sorts. It was this: Man is capable of both great good and great evil (see under: Cain and Abel), which is why we, poor souls, are constantly in need of moral instruction to help keep us on the up and up. “Moral instruction” being the sort of medicine that can, if administered imprudently, do more damage than good, it is therefore a good idea to entrust its development and application to the cautious wisdom of the ages. Enter tradition, a way of life that allows for gradual change but holds that, when faced with a thorny new problem, first look to your grandmother for advice, because there is nothing all that new under the sun.

Against this, the Enlightenment offered a radical countervision. Man, it argued, was born good; it was only the oppressions of coercive institutions that drove him to contemplate and commit evil deeds. Benjamin Franklin, for example, was riffing on this idea of the Noble Savage when, observing the Iroquois, he noted in 1770 that “… the Care and Labour of providing for artificial and fashionable Wants, the Sight of so many Rich wallowing in superfluous Plenty, whereby so many are kept poor distress’d by Want. The Insolence of Office, the Snares and Plagues of Law, the Restraints of Custom, all contribute to disgust [the Indians] with what we call civil Society.”

How, then, to keep civil society from making us ungood? Enter the social contract, liberalism’s mighty engine. Willingly sign away a host of your innate rights, and in return the authorities—the king, the president, a majority of your peers, whatever—will protect you and safeguard all of your other rights.

For a while, the Enlightenment did alright for itself and for us, in no small part because it was never allowed to run rampant. Other, older, sturdier forces—the family, mainly, but also the church—threw around their own familiar weight, reminding us every so often of the limitations of radical individualism and social contract theory. We might be enlightened human atoms in our laboratories and offices, but the majority of our lives were spent swimming within the older and deeper currents of family, community and religious life.

Until, that is, the church and the family began suddenly and precipitously losing ground. Why that happened is the subject for several weighty tomes, but the numbers don’t lie: Membership in houses of worship this year dipped below 50% for the first time in American history; so has the number of American children who can expect to spend their entire childhood with both biological parents. And they’re the lucky ones, simply by virtue of being born. During the pandemic, when American couples spent unprecedented amounts of time indoors together, birth rates continued to plummet, last year hitting the steepest annual decline in 50 years. Liberalism, left unchecked, has become what it was always angling to be: a social death pact, leaving its adepts without the motivation to reproduce themselves.

Liberalism finally got what it always wanted: a gaggle of detached and uprooted people, alone and scared witless, seeking solace, and suspecting that someone, somewhere is out to get them.

Talk to liberalism’s defenders—in academia, science, media, the arts, or politics—and they’ll give you some version of the following defense of the faith: Liberalism works because it is a healthily skeptical system that rejects all measures of bullshit and focuses instead only on what can be empirically proved. Everything else, all the juju of those benighted bobos who claim to know what the Big Man in the Sky wants them to think, eat, and do, is all rot. The system’s chief virtue is that it liberates human beings from the shackles of the false and malignant beliefs that religion once foisted on benighted believers.

Except that liberalism, of course, is itself a form of religious belief, and has been from the very first. As Williams College professor Darel E. Paul wrote recently in the Christian magazine First Things:

We know this not only from the works of liberal philosophers, but more importantly from actually existing liberalism, the everyday beliefs and practices of liberal societies. Liberalism has an anthropology, a vision of the human person as bearing the capacity and the obligation to become a radically autonomous individual beholden to no moral authority save that which he has chosen through a fully rational and constantly reenacted choice. Liberalism has a mythos, with the State of Nature, the Social Contract, the Original Position, the Dark Ages, the Wars of Religion, the Triumph of Reason, and Progress making up its narrative. Liberalism has an ethos: a humanitarian impulse toward the eradication of physical and psychological suffering. Liberalism has a politics: a limitless expansion of legally codified rights defined and defended by a representative state …

Is it any wonder, then, that said state is ascendant and now busy policing any and all virtues and vices, whose number would appear to be infinite? And is it really surprising that, left without any other way of adjudicating moral and ethical matters, liberalism now resorts to the one thing it was ever truly good at, namely mediating quibbles between various parties seeking power? Now that we all live in broken homes, avoid houses of worship, and spend much of our time alone, staring at screens, liberalism finally got what it had always wanted: a gaggle of detached and uprooted people, alone and scared witless, seeking solace, and suspecting that someone, somewhere is out to get them. Call it woke culture if you’d like, but it’s nothing more than the Enlightenment’s apotheosis—and it’s exactly why folks everywhere from Warsaw to Wisconsin are voting for candidates who promise little more than a swift kick in the pants to the liberal order.

Of course, our smarties are slow on the uptake. These hopelessly educated and tragically remunerated cats still believe that America is, as the political scientist Michael Millerman recently put it on Twitter, a collection of classrooms: If you don’t like the action over at 502, where they teach leftism, move over to 503, where they profess conservatism. It takes little more than a casual glance and an ability to drop the ossified and useless terms that helped previous generations chug along to understand that “conservatism,” as we understand it, is a sub-Reddit of classical liberalism. It doesn’t much matter whether you identify as a Republican or a Democrat, or subscribe to The Wall Street Journal or The New York Times. For all the real differences between them, Edmund Burke’s reserved table at the Capital Grille is just across the dining room from Thomas Paine’s.

The way out of this morass isn’t to choose a slightly different flavor of a fermented mess. It’s to opt for a different system altogether. Which one? That’s easy: the one that always wins. The one that has seen a long parade of empires rise and fall. The one that kept at it as isms flared and burnt out. The one that still has us today praying in precisely the same words our ancestors did two millennia ago. The one that survived, either because it was astonishingly lucky or inherently true, whichever better suits your sensibilities.

Don’t get me wrong: this is in no way an insistence that to survive the tsunami of stupid you must begin immediately living your life as an observant Jew, though some, myself included, find meaning and joy in practicing some parts of the religion more or less as Zayde and Bubbe did. But it is an invitation—an exhortation—to understand that the solution to liberalism isn’t to debate it on its own terms or to ask politely that it be slightly less steely when it cuts us. Because the liberal answer will always be: Too bad for you. The rules are the rules.

The only way to be free of liberalism’s rules is to find a different place to stand. To posit, and embrace, an alternative—and superior—set of values, which allows to look down from the mountaintop on the legions of miserable, lonely, loony souls, and be infinitely glad that you are not one of them. Too bad for you, pal.

To the incoherent yowls of critical race theory that require public confessions and assign guilt on the basis of 19th-century pseudoscience, we can say that our system of justice, the one rooted in the words of the Hebrew prophets, is better, which is why it—and not some soulless and mindless academic dross—inspired every civil rights leader who mattered, from Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass to Martin Luther King Jr. To the ninnies who march around blindly with the banner of equity, we can say that we don’t believe in equity—that’s part of your messed-up belief system. We believe in excellence, the simple idea that allowed minorities in this country, Black and white alike, to smash the ceilings that kept them cowering, and realize the fullness of their own God-given human potential. To the slicksters who chew our ears off ad infinitum by counting how many millionaire women of color are on the cover of the latest glamour magazine, we say politely that our tradition teaches us to care for the poor, and that, not being rank racists or silly sexists, we don’t much care if the poor are male or female, Black or white, male or female, down the block or across the country. Our religious tradition is better at handling these questions and quibbles if only because it has done so, successfully, for 2,000 years, which is a major leg up on liberalism’s mere three centuries or so.

So what’s wrong with America these days? It’s liberalism, stupid. And how do we fix it? By doing exactly what Uncle Sam recommended we do in that 1975 hot dog commercial: Answer to a higher authority.

Liel Leibovitz is editor-at-large for Tablet Magazine and a host of its weekly culture podcast Unorthodox and daily Talmud podcast Take One. He is the editor of Zionism: The Tablet Guide.