Lithuania’s Museum of Holocaust Denial

Yom HaShoah/Holocaust Remembrance Day: A state-sponsored institution in Vilnius rewrites history to the delight of Europe’s new ultranationalists

This past winter here in Vilnius, the charming capital of Lithuania, was much like any other. During long solid weeks of subzero temperatures, as the flow of tourists and roots-seekers slowed to a trickle, I adjusted the route of my daily walk to pass by up to a dozen top tourist sights. Day after day, there was one constant: The most popular, winter-defying “must-visit” for foreigners is “The Museum of Genocide Victims.” Perhaps there is something grotesquely sexy about “genocide.” Maybe the promise of (real) former KGB interrogation rooms and isolation chambers in the basement is less run-of-the-mill and more strikingly authentic than much usual museum fare. Estimates obtained from the museum’s administrators suggest about a million visitors total to date.

Called “The Genocide Museum” for short, the city’s premier attraction is housed on the central boulevard in an elegant Russian imperial building completed in 1899 that was formerly used for the courthouse of the empire’s Vilna Province. The museum’s current headquarters are located in an annex dating to 1914-1915, just prior to World War I, which brought that empire tumbling down. Vilna would then change hands (depending how you count) around seven times through to 1920, when it came under the stable rule of the interwar Polish Republic, a rule that lasted until the Hitler-Stalin pact brought on Poland’s dismemberment in September of 1939. Then came little over a month of Soviet rule of the city (Sept.‒Oct. 1939), a little over a half-year of Lithuanian rule (Oct. 1939‒June 1940), a year of Soviet rule (June 1940‒June 1941) three years of Nazi rule (June 1941‒July 1944), 46 or 47 years of Soviet rule, and since 1990 or 1991, depending from when you prefer to reckon, the beginning of close to three decades of modern democratic Lithuanian sovereignty. Somewhere around the halfway mark of this modern period, in 2004, the country, along with a number of neighboring states that had been freed from Soviet yoke and became successful democracies with growing market economies, joined NATO and the European Union, cementing their firm and proud anchorage within the West.

This particular building had a starkly macabre function during two of its signal incarnations. It was the German Nazi Gestapo headquarters, with its own interrogation rooms, prison cells, and death chambers. Then for decades, it was a Soviet NKVD/KGB central facility used to coordinate terrorization of the undesired part of the population, particularly dissidents and resistance figures, who were incarcerated, interrogated, and tortured in its cells and shot on its premises during the Stalin years and beyond.

***

It is all the more eerie, painfully so, to have to say that this building now mars the pleasant Vilnius ambiance of the delightful, freewheeling city center in a raw, soul-destroying sort of way. Not because it tells the story of dark and brutal chapters of history. Those stories must be told. They are told in major museums in city centers around the world.

Moreover, there is no country on the planet without major blots on its history. It is a sign of maturity when for example the United States has museums dedicated to the national crimes of slavery, horrors against Native Americans, and commemorative sites for many others who were victimized and mistreated. Though far from perfect, these efforts indicate an elementary sense of national honesty, in dealing with the past that is, whether we like or not, very much part of our present. The “reconciliation” part of this effort has a lot to do with tolerance for minorities who may not see the “mainstream” historical narrative or its foundational heroes quite the way the standard schoolbooks like to have it, but who are nevertheless patriots who serve their country just like everyone else. America got some small “echo of a taste” of all that last summer in Charlottesville, Virginia. The proximate cause of discontent was the fate of a long-standing statue of Confederate States General Robert E. Lee.

So let us try a little “thought experiment”: Imagine not a statue of General Lee in Charlottesville, but an elaborate state-sponsored museum in the nation’s capital, in which the Confederate forces are depicted as pure heroes of independence and freedom, fighting off the central government of tyranny, and African Americans turn up only occasionally as evil collaborators with the Northern tormenters who came to destroy their beloved civilization. An American constitutional scholar might well explain why such a counter-historical museum, founded on intellectually and academically filtered racial hatred, could well be legal on someone’s private property as their own private realm but must not occupy public space. In the hands of specialists, it can all be made to look rather convincing to the proverbial outsider from Mars.

In Lithuania, the murder rate of around 96 percent of the Jewish population during the Holocaust was among the highest in Europe, which incidentally makes the bravery of those who did the right thing and rescued someone all the more inspirational. They were regarded as betraying their own nationalist cause. They are the people who should be honored throughout the land starting with a museum in the capital.

In today’s incarnation of the Genocide Museum, a stone’s throw from the nation’s parliament, there are no longer individual human victims in the flesh. The victim here, in the 21st century, is the truth. The point of the museum is to persuade all comers that Soviet crimes were the genocide that took place in this part of the world and that those groups to which most of the museum’s space is dedicated to glorifying were indeed humanitarian lovers of truth, justice, and multi-ethnic tolerance. The sad truth is, however, that many of those honored were collaborators who participated in, or abetted, genocide. There lies the heart of the title “Museum of Lies,” which Holocaust survivors here (now mostly gone) would use over these last decades to describe the project.

But there is one theme in this museum that is very honest, and necessary, and if it is one day disentangled from the Fake History components—and those components discarded—it would make a truly excellent Museum, namely a cabinet of KGB Crimes and Stalinist Horrors such as one finds in numerous other cities. These exhibits expose Soviet crimes against humanity, particularly in the Stalin period, including mass deportations, imprisonments and harsh punishments, including torture and barbaric murder, of supposed “enemies,” suppression of human freedoms including speech, religion, emigration and political beliefs, and, pervasive from morning to night for all those decades, a cruel forced occupation of one’s country by a larger empire with the resultant loss of freedom, identity and myriad basic human rights.

If the ghosts of KGB tormentors still linger in those cellars, they can only be giggling that their own cruelty is presented as part of a twisted tale in which the legitimacy of anything and everything sinks into some murky postmodernist mush under the inane heading of Everything is Equal.

The ‘LAF Rebellion’

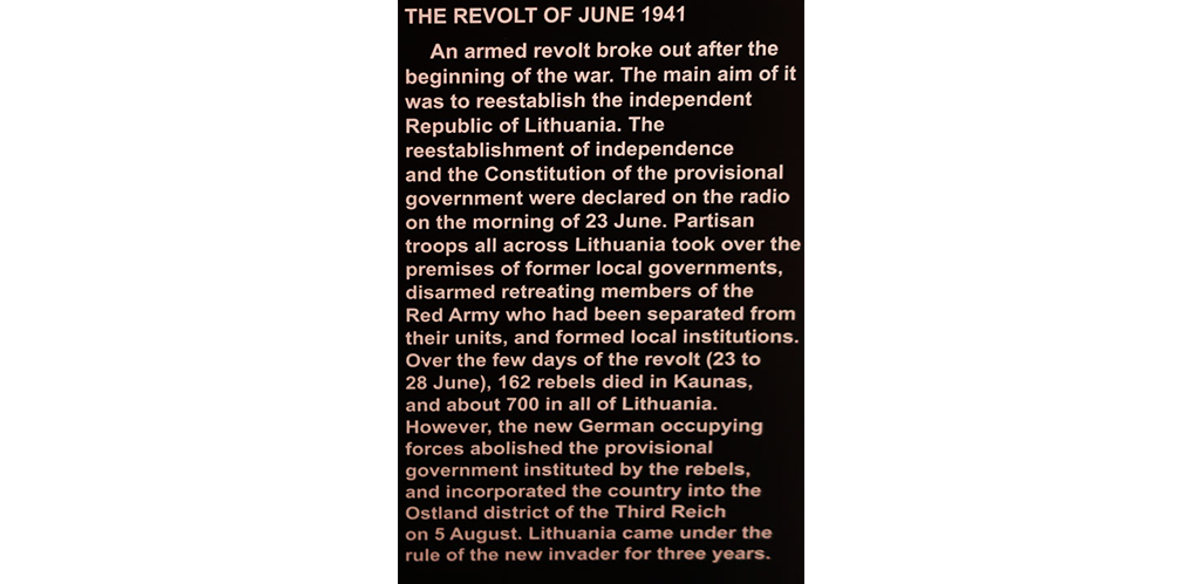

The first major dynamic historical episode encountered in the Genocide Museum is a series of exhibits lavishly dedicated to the 1941 Lithuanian Activist Front (“LAF”) white-armbanded fascists whose “pre-Nazi invasion central planning” came from Berlin, and included a group of high-level Lithuanian Nazis, adherents of ethnic cleansing (to put it politely) stationed there in the months before the Nazi invasion of the then Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. But as the Soviet occupation collapsed in disarray on the day of the Nazi invasion, and especially the following day, Monday, June 23, 1941, many nationalist young men rapidly joined the “LAF” militias, often by donning a white armband and just “becoming LAFers” or joining related militias and gangs at will. With or without the armband, with or without documentary affiliation to the LAF, they have all come to be known as the “White Armbanders” in the local languages (Lithuanian Baltaraiščiai, Polish Białe opaski, Russian Bielorukavniki, Yiddish Di Váyse Órembendlakh, and so forth). Accompanied by a sham radio-address “declaration of independence” (that included the oath of loyalty to Adolf Hitler—woe to such “independence”), they took over post offices, police stations, and town halls vacated by the fleeing Soviet forces for several days before turning them over, unctuously and with sumptuous servitude, to the arriving Germans.

The museum’s exhibits tell a very different story, which is not rooted in historical fact. A tall tale: that this was all a “rebellion” of the Lithuanian people against Soviet rule. That story is shameless nonsense. While the Soviets were in power, these White Armbander and LAF folks did not fire a single shot at any Soviet official or military installation. When the Soviets were fleeing for their lives from the Nazi invasion, the local militants fired at their backs and took over some freshly-vacated installations. (To be clear, the KGB and its affiliated organs did brutally murder many political prisoners and others in their last hours on the soil of the lands they had occupied in 1939 or 1940 all along the front of the arriving Nazi invasion forces.)

Put simply, you cannot “rebel” against an authority that has collapsed because of someone else’s attack, the less so when the folks you are “rebelling” against are already fleeing. Nor do you have much moral authority when your main “activity” during those days was butchering your Jewish neighbors. In other words, there was no rebellion. And, it goes without saying that the Soviet army was fleeing Hitler’s invasion, Operation Barbarossa, the largest invasion in human history. As surely as water is wet, the Soviet Army was not fleeing the local Lithuanian White Armbander Jew-killers.

For that is, alas, what the White Armbander “Lithuanian nationalists” were doing in the final week of June 1941. They initiated the first phase of the Lithuanian Holocaust, murdering Jewish civilians, particularly younger women and older rabbis, often in macabre city-center shows of “victory,” such as the teenage Jewish girl cut in half in the center of Šiauliai (in Yiddish: Shavl), or Rabbi Zalmen Osovsky’s head put in a shop window in Kaunas (Kóvne). The late Professor Dov Levin, historian of the Lithuanian Holocaust, documented 40 locations in Lithuania where the actual murdering began before the arrival of German forces. If we add violence causing serious injury, plunder of property, humiliation, degradation and dehumanizing treatment, it is hundreds of places, not 40. And if we add the places where many of the same murderers continued on under German administration, the kill rate grows exponentially. But this is not about numbers, though the numbers of Jews killed by the LAF-affiliated White Armbanders is in the thousands, with the biggest single concentration in Kaunas itself. Kaunas was the interwar de facto Lithuanian capital and center of the “rebellion.” (Vilna, prewar Wilno, in Yiddish forever Vílne, was still a largely Polish city at the time, and there were vastly fewer instances of pre-German lethal violence in the city and its area, that Stalin had “given” to Lithuania in October 1939 when it became Vilnius.)

But what does the Genocide Museum’s exhibit tell us about these LAFers’ deeds? Not a word about their rampage of murder that unleashed phase one of the Holocaust in the country. Instead, the story told is illustrated by this key panel:

This text (which like all, appears bilingually in Lithuanian and English) has caused such anguish to local Holocaust survivors and their families over the years that many found it too painful, or too enraging—or both—to even set foot in the place. Survivors are unanimously quick to point out, incidentally, that in addition to “occupying the just-vacated post offices and police stations,” murdering and humiliating Jewish neighbors, the LAF actually did “something else too.” On the roads crisscrossing the country, outside hundreds of towns, they created a ring of armed militants who prevented the flight of Jewish people who were attempting to flee eastward to Russia (the only hope for survival for a Jew in this part of the world—there were no American or British forces around). Fleeing Jews were sent back into the Nazi choke-hold until the Germans could arrive to “organize it all properly” (which took the form of organized mass shootings at around 230 major mass grave sites that dot the country today). Holocaust memoirs contain hundreds of eyewitness statements about the white-armbanders and their cohorts preventing Jews from escaping even when all their property was left behind for the taking. These then are the LAF white armbanders celebrated in this museum as “heroic rebels.”

Needless to say, it is nowhere mentioned that the LAF masterminds in Berlin in the preceding months had published leaflets and entire works calling for the removal of Jewish citizens from Lithuania. These were no street thugs. They were educated people who knew their history. One infamous leaflet declares the charters of toleration issued by the Lithuanian Grand Duke Witold (Vytautas) in the 14th century to be “completely and finally revoked.” That Lithuanian leader’s charters of tolerance were a highpoint of European civilization in the middle ages, and he became known as “The Cyrus of Lithuania” to many generations of Litvaks, or Lithuanian Jews. I am proud in my home to follow a tradition of hundreds of years of Jews here of having a portrait of Witold near my front door.

Before going any further, however, let us be very clear that the launch of the 1941 genocidal phase of the Holocaust by the White Armbanders, and by their fellow “partisans” in Latvia, Estonia, and western Ukraine, among other places, does not mean that any of these nations are “bad.” The guilty alone are responsible, and their supporters and enablers. All these nations had, as noted, inspirational rescuers who risked everything to save a neighbor in danger (the “Righteous Among the Nations”). All these nations have their storied poets, statesmen, military heroes, scientific geniuses, architects, artists, and much more.

So why would anyone in the 21st century, much less anyone fortunate enough to be in the NATO and European Union area, choose to falsify the history of these first days of the Holocaust in order to turn Holocaust-initiating thugs into “national heroes” to be featured in museums as “rebels,” “partisans,” and “freedom fighters”? That question requires serious study, a task that has been shirked by many historians in these recent days of “The New Cold War.”

But just scratch a historian, diplomat, or political PR person involved with such things in this part of the world and you’ll get an answer, one that is probably part of the answer. Ultranationalist elements, consumed with (understandable) resentment against the many crimes of the Russian and Soviet empires over the centuries, will go to any length to make heroes out of all anti-Soviet and anti-Russian manifestations in history, including Hitlerism and—to hell with the “detail” of the extermination of a national minority. The problem here is that virtually all of the many thousands of actual East European Holocaust murderers were “anti-Soviet.” If that makes them heroes, ipso facto, heaven help European civilization.

During the genocidal phase of the Holocaust, from June 22, 1941 onward, the Soviets were of course in the Alliance with Great Britain and the United States, where they remained until war’s end. But there are also many subtly local aspects in play. For example, many ultranationalist historians in all three Baltic states are “ashamed” that their people barely fired a shot against the “peaceful” Soviet annexation of their countries in 1940, and a “revolt” in 1941 seems like a darned good idea for stitching up a patriotic narrative of “resistance.” Again, these nations all have grand patriotic histories, which in the Baltics includes the magnificent rise to independence of democratic states in 1918, and then again in 1991.

‘Double Genocide’ and ‘Holocaust Envy’

The post-Soviet East European nationalist decision to glorify Hitler collaborators is situated very near the conceptual core of the current set of Holocaust issues in Europe and beyond. The far-right jewel in the crown is the Genocide Museum in Vilnius. The other regional museums infected with the same virus are more in the dressed-up-for-export mode of “Double Genocide,” the theory that Nazi and Soviet crimes are in principle equal and that that equality must guide the study and application of European History. That theory has come to be, in effect, the 21st century respectable-in-high-society successor to the previous century’s classic Holocaust Denial. It came to its fullest expression in the 2008 Prague Declaration. (Disclosure: I was privileged, in 2012, to co-author, with Danny-Ben Moshe, the European parliamentary rejoinder known as the Seventy Years Declaration, signed by 70 European parliamentarians, including eight particularly courageous ones from Lithuania, all incidentally Social Democrats.)

Unlike Vilnius’s Genocide Museum where Soviet crimes are presented in fact as The Genocide, the others follow the model of “equality” of the Prague Declaration, that insists on “equality” as the absolute principle of European history and the point of departure for all else. For example, the House of Terror Museum in Budapest, founded in 2002, features on its outside roof-corner display both the arrow cross (the local fascist wartime symbol) and the Soviet star side by side in an exposition of equality, echoed by two huge panels with the same symbols in the welcoming hallway (in case someone missed the message outside). The Museum of Occupations in Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, founded in 2003, welcomes visitors with an elaborate piece of Double Genocide modern art, with the Soviet star and the swastika atop equal commanding pillars. Much older than both is Riga’s Museum of the Occupation of Latvia, founded in 1993, where recent revisions have taken harsh Western criticism into account, though the system of “red” (Soviet) and “brown” (Nazi) panels gives the immediate impression that the Soviet issue is the main one, as it is in space dedicated. But to be fair, this is called a museum of the Occupation, not of Genocide. The most recent addition to Eastern Europe’s macabre litany of “anti-Holocaust museums” (in the sense of negating the Holocaust’s place in history and consciousness) is the Lonsky Street Prison National Memorial Museum, founded in 2009 in Lviv (former Lvov, Lemberg, Yiddish Lémberik), which has prominently featured a photoshopped photograph of a woman looking for her murdered Ukrainian relatives in 1941 with the piles of Jewish corpses in the image covered over by circles indicating numbers of Ukrainian victims far and wide.

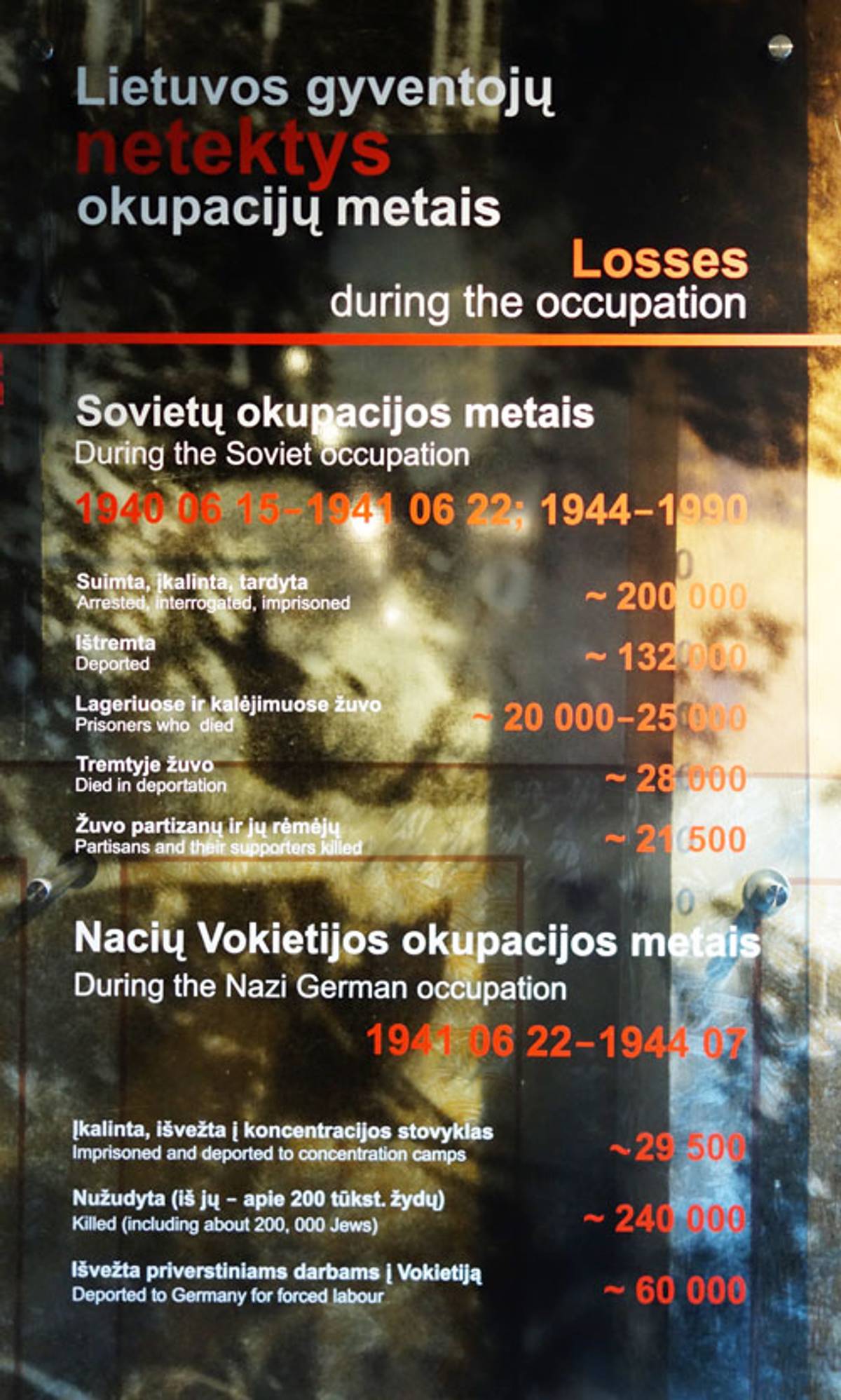

That brings us back to the mother of East European genocide museums, the Museum of Genocide Victims right here in Vilnius. While its main message is much more extreme than its sister museums in Eastern Europe, there have for many years been hints of the compulsion for comparison that “must” lead to some sort of equality. The ascendant phenomenon called Holocaust Envy comes to the fore at the Genocide Museum in a large bilingual chart on the main floor, toward the rear of the corridor near the restrooms, in other words away from the actual major exhibit rooms. “For the foreign Jews,” as a former museum employee once quipped to me. For many years, until 2011, this was the only “oblique” and nameless reference to the Holocaust in the entire “Museum of Genocide Victims.”

A lengthy analysis of this chart could be penned, a chart that contained the only mention of what happened to the Jews of Lithuania between the museum’s founding in 1992 and late 2011. For here a few salient points may suffice. First the use of the word “losses” to cover the Jewish victims of the campaign of genocide to murder every Jew in the country as well as an array of other categories of state crimes: “arrested, interrogated, imprisoned,” “deported,” “prisoners who died,” “died in deportation,” “partisans and their supporters killed,” for the Soviet side of the ledger; and then for the Nazi side: “imprisoned and deported to concentration camps,” “killed” and “deported to Germany for forced labor”. The penultimate category, “killed” has the addition in parenthesis: “including about 200,000 Jews,” which is not only “lost in the list” but comports exactly with what the eye first saw above, “Arrested, interrogated, imprisoned” with, lo and behold, also 200,000. This is all related to the inflation of the word genocide by the ultranationalist camp, which was boldly exposed by the late, lamented Lithuanian philosopher Leonidas Donskis.

Such equivalencies are no quirks of some statistical modelling. They are part of two interrelated, and weird, phenomena that represent different stages of the Holocaust revisionism tendencies of Eastern Europe. First is in fact Double Genocide, the notion that the starting point for the subject is the universal acceptance of the Nazi and Soviet regimes’ brutality being “the same.” Second is a deeper feeling, just under the surface, that in some profound sense the Holocaust must be regarded as the lesser of the two phenomena.

Since 1997, the Genocide Museum has been under the auspices of a state-financed institute with close ties to the highest echelons of power, called the “Genocide and Resistance Research Center of Lithuania” or, for short, “the Genocide Center.” For years its website carried a page on the “two genocides” that included this gem of Holocaust Envy: “One may cut off all four of a person’s limbs and he or she will still be alive, but it is enough to cut off the one and only head to send him or her to another dimension. The Jewish example clearly indicates that this is also true about genocide. Although an impressive percentage of the Jews were killed by the Nazis, their ethnic group survived, established its own extremely national state and continuously grew stronger.” For many years, one of its “chief specialists” was also a leader of the neo-Nazis in Lithuania. Recently, a bold Californian-born Lithuanian scholar who settled in his ancestral homeland years ago, Prof. Andrius Kulikauskas, has boldly taken on its leadership, which frequently defends the ethnic cleansing policies of various purported national heroes.

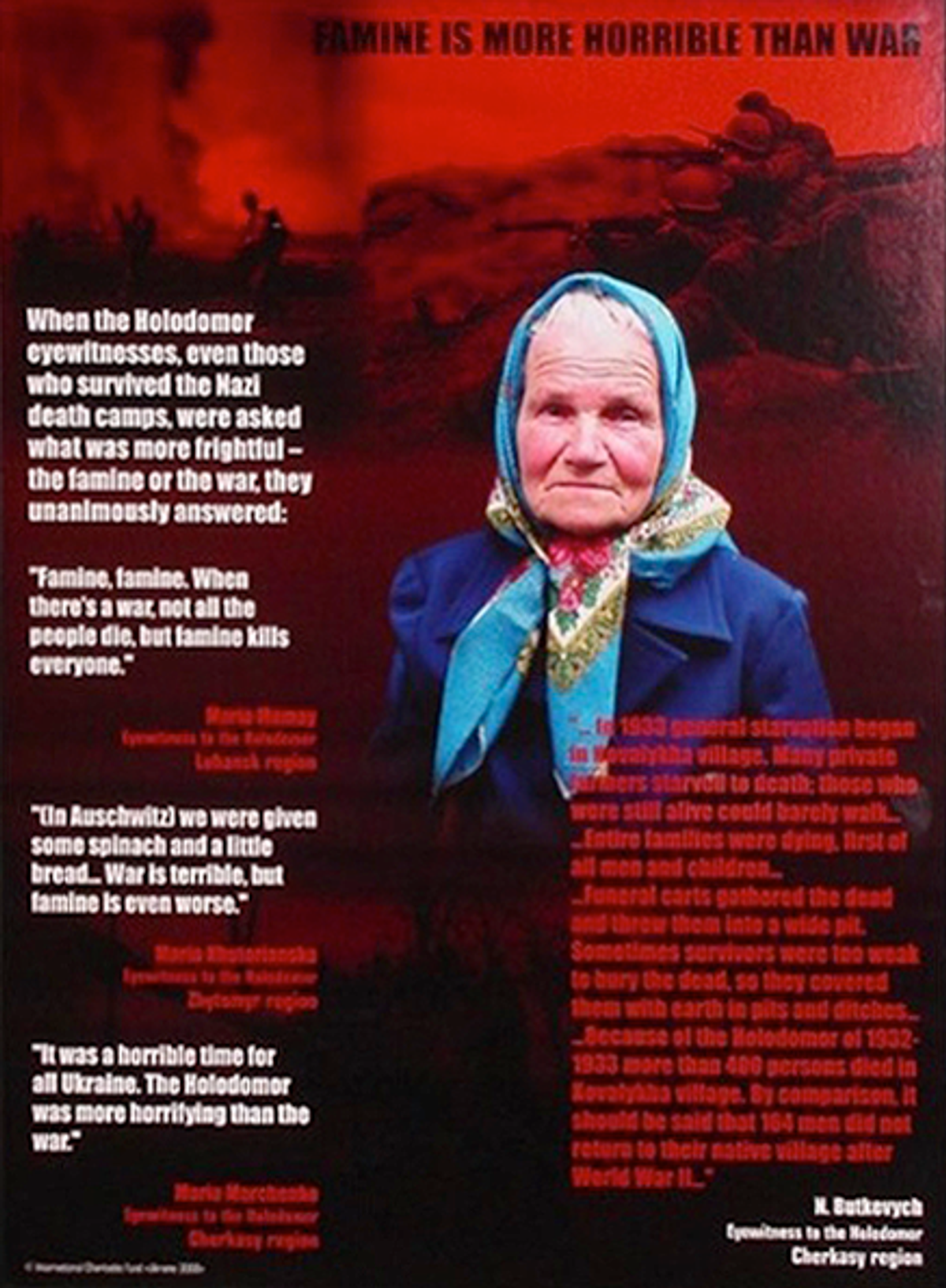

Analogous points have been scored in visiting exhibitions. For some years it was this comparison in an exhibit on the Ukrainian famine, or Holodomor, which for years was the only word starting with h-o-l-o in a museum of genocide in Eastern Europe. The museum told its visitors that “When the Holodomor eyewitnesses, even those who survived the Nazi death camps, were asked what was more frightful—the famine or the war, they unanimously answered: [a number of quotes follow, including, under the image of an elderly woman, her quote]: In Auschwitz, “we were given some spinach and a little bread. War is terrible, but famine is even worse.” No mention of the fate suffered by the statistically overwhelming victims of Auschwitz or who they might have been. Such is the face of our new century’s Holocaust Denial: Talking the Holocaust out of history without denying a single death, or for that matter, fact, through rhetorical analogies and false comparisons.

The ‘Forest Brothers’

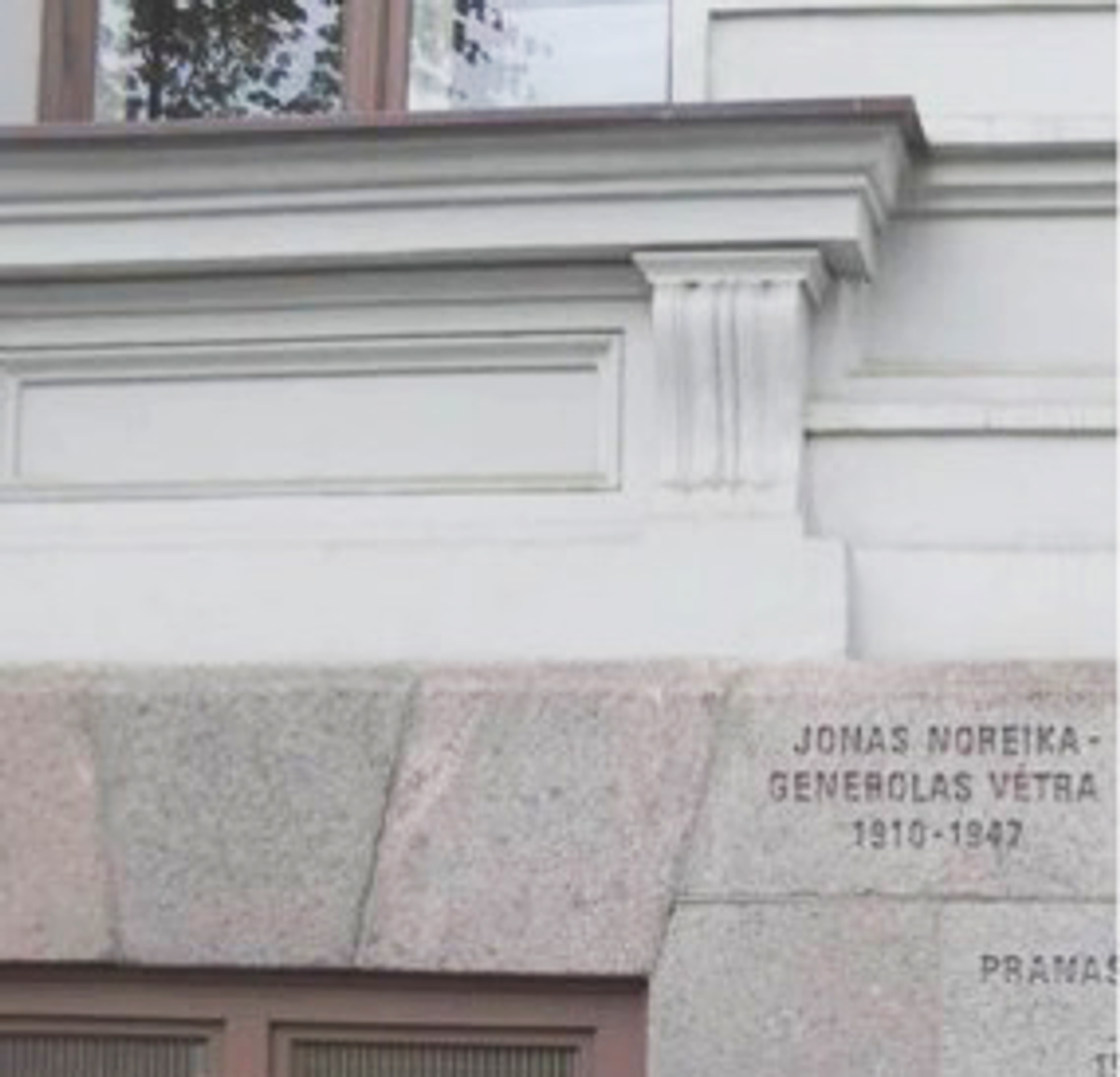

A vast portion of the “Museum of Genocide Victims” is dedicated to “The Partisan War Between 1944 and 1953.” Popularly known as the “Forest Brothers,” these were the resistance fighters from the time of the defeat of Hitler’s forces in 1944 until around 1953, who opposed Soviet rule and carried out armed attacks. Not all of these fighters were recycled murderers of 1941 but a disputed number were. Most painfully, a number of their leaders are now extolled as national heroes for resisting the postwar Soviets, as if their involvement in the Holocaust is a minor, disregardable detail of history that must not spoil the heroic resistance party. The fearless Lithuanian ethicist Evaldas Balčiūnas has published exposés using solid sources concerning the Holocaust participation of a number of the “heroes” extolled in the museum as martyrs for justice, freedom and democracy. Asking why his state’s authorities glorify murderers, Balčiūnas went on to publish a series of articles on individual heroes extolled in the Museum of Genocide Victims who were actually collaborators with the perpetrators of the genocide that actually occurred in the country. Among those that have appeared in English translation are his pieces on Antanas Baltūsis-Žvejas, Juozas Barzda, Konstantinas Liuberskis–Žvainys, Vincas Kaulinis-Miškinis, Juozas Krikštaponis (Krištaponis), Jonas Noreika, Adolfas Ramanauskas Vanagas, Juozas Šibaila, Sergijus Staniškis Litas, and Jonas Žemaitis. One of the most notorious, an actual participant in the Holocaust, Jonas Noreika, has a stone block outside the building, on Vilnius’s main boulevard, dedicated to his memory.

Instead of the medal he deserves, Evaldas Balčiūnas was hit with police visits to his place of work, summonses, and a series of nuisance court cases that finally, after a dozen 280-mile round trips from home, came to a not guilty verdict in July 2016. But the message was clear: The country is a democracy for 99 percent of topics but not for far-right choices on historical narratives related to the Holocaust, which are enforced by the power of the state. In 2011, the late Joe Melamed, longtime head of the Association of Lithuanian Jews in Israel, was visited by Interpol in his Tel Aviv office because some of the same names appeared in his 1999 book Crime and Punishment; the harassment of Melamed made it to the British Parliament. After questioning the postwar bonafides of one of these “heroes” a best-selling Lithuanian author known (and widely criticized) for her lurid sensationalism, Ruta Vanagaite, in late 2017 had her books banned by her own publisher, in an episode that reached the New Yorker. There is little doubt that the real reason for the ban was a 2016 book she coauthored with famed Nazi hunter Dr. Efraim Zuroff that revealed the extent of Holocaust participation by local forces.

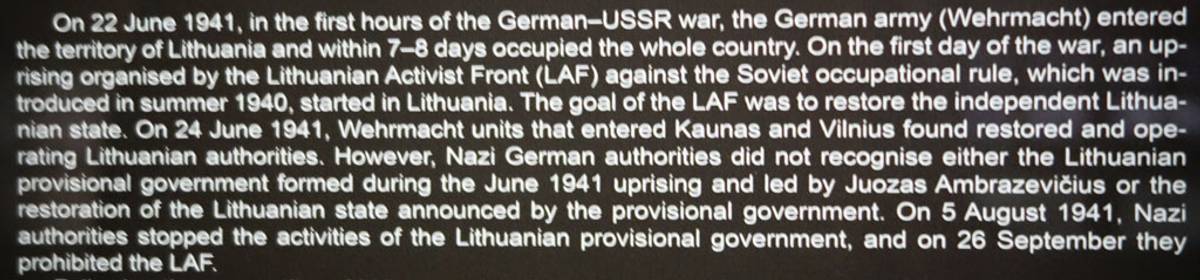

Until 2015, the museum’s large halls dedicated to glorification of the “Forest Brothers” also contained three blatantly anti-Semitic caricatures that appear in a section on the Brothers’ underground artwork and literature. One features a jeep driven by Lenin, Stalin, and “Yankelke the Jew,” a second shows a coarse caricature of a Jew behind Stalin blowing economic bubbles (along with a soap dish adorned by a Star of David should someone miss the point). The third depicts an anti-Semitic caricature of a Jew serving as a Soviet torturer of Lithuanian patriots. These images all date from after the Holocaust (at right).

In 2015, after numerous complaints, these three images disappeared from the exhibit on the Forest Brothers’ underground art. In reply to our question for this article on whether the removal was permanent, museum director Eugenijus Peikštenis said (in a written reply): “Exposition of the museum is constantly updated—one exhibit is replaced by another.”

The best known free-thinking, critical book here on the Forest Brothers, one that is a great credit to Lithuania, Memorial Book for the Victims of Partisan Terror, edited by Povilas Masilionis, appeared in 2011. It comprises his introduction in three languages (Lithuanian, English, Russian) followed by a list of some 25,000 names of people, nearly all civilians, murdered by the Forest Brothers, who were notorious for killing fellow Lithuanian citizens they considered “collaborators” with the Soviets, including those who led or worked on collective farms and other Soviet enterprises (as if people had a choice about where to work under the autocratic and dictatorial Soviet rule). Masilionis concludes his forward to the book, aptly named “Victims of the Unbrotherly ‘Forest Brothers’ ” with the plea: “Books of memory should be published in every city and every region. Even a national Memory institution could be established to defend the rights of relatives of terror victims and to defend the memory of murdered unarmed civilians.”

Before that, in 2009, Lithuauanian historian, Mindaugas Pocius published his academic monograph, The Far Side of the Moon, which reported “only” some 9,000 innocent civilians murdered by the Brothers (including 300 children). He too became a victim of nuisance prosecution, intended to defame and to deter others more than to find guilt with someone exercising their European Union right of freedom of expression. Last year, the mayor of Vilnius fired Dr. Darius Udrys, the American-born head of the capital’s “Go Vilnius” development agency, after he dared ask on his own Facebook page whether Lithuanians who worked for Soviet collective farms in the 1950s actually deserved to be summarily executed.

Lithuania is a democracy for 99 percent of topics but not for far-right choices on historical narratives related to the Holocaust, which are enforced by the power of the state.

The ultranationalist-controlled academic establishment at major universities plays its part too in stifling free debate, especially since a 2010 “Double Genocide” law made it a crime to disagree with the state model, one punishable by up to two years in prison. (Disclosure: That was the year I was myself discontinued as professor of Yiddish at Vilnius University after 11 blissful, incident-free years; I was told it was because I had published “false articles in three radical left-wing newspapers,” a reference to two 2009 articles in London’s Jewish Chronicle and Dublin’s Irish Times and the final straw, a 2010 piece in the Guardian.) Vilnius has a tiny, separate Holocaust museum, out of sight on a hill up a driveway, whose longtime fearless director, Rachel Kostanian, now retired, was repeatedly harassed for her determination to just tell the truth. On more than one occasion, the late Sir Martin Gilbert would truly play the part of the white knight who would step in to save her job. The saga became the source for much dark humor on all sides of the debate. Nobody has gone to prison, but freethinking, talented Lithuanian young historians continue to flee the country for studies abroad before even thinking about staying to face ruined careers.

Thankfully, the Lithuanian people have vastly more common sense than the far-right elite that has usurped control of the country’s official historical narrative. In 2015, there was a proposal to rename a high school in the town Obeliai (known in Yiddish as Abel), in northeastern Lithuania, in honor of a Forest Brother leader whose memoir had recently been published. The school’s leaders did something very intelligent and quite simple. They organized a poll, by secret ballot. A majority of the town opposed the proposal.

But the clique of ultranationalists controlling “state history” keeps going further in the other direction. Another alleged Holocaust collaborator who became a postwar Forest Brother leader, Jonas Žemaitis, was incredibly proclaimed to be the de-facto “fourth president of Lithuania” by the nation’s parliament in 2009. And, in December of 2017, the parliament declared 2018 to be the year honoring yet another alleged Nazi collaborator, Adolfas Ramanauskas (Vanagas).

Whenever a Holocaust-tainted militant is chosen for honors, it is a de-facto message of adulation for fascism and not-so-latent glee at the greater ethnic purity rendered by the Holocaust and its related events. Believe it or not, the Lithuanian Foreign Ministry (which squanders vast sums on history and Holocaust manipulation) had arranged to pay for a monument to Ramanauskas in the Connecticut town of New Britain (where Ramanauskas happened to be born, before his parents returned to Lithuania). The mayor’s office was rapidly persuaded. And why not—no mention was made of his Holocaust-era activity, only his postwar anti-Soviet activity. Here in Lithuania, the “American monument for Ramanauskas” was flaunted for months in the media in the triumphalist spirit of demonstrating how America now accepts the East European nationalist narrative of Holocaust history. Moreover, there is no (known) evidence Ramanauskas personally killed anyone during the Holocaust, though he boasted in his memoirs of leading one of those (Hitlerist, LAF-affiliated) groups of “partisans” in the first days of the Holocaust. Is that the kind of symbol of heroism the free world wants to bequeath to future generations?

When our Vilnius-based web journal Defending History posted an appeal to the New Britain mayor in January 2018, after writing to her office, there was no immediate response. A lively internal debate then ensued within the New Britain city council. Several weeks ago, that debate ran into the single determined force of elected city alderman Aram Ayalon, a professor in the education department of Central Connecticut State University. He rapidly launched a petition and alerted local media. The New Britain Progressive published a report on 2 April. Last Friday, April 6, Justin Dorsey of the mayor’s office circulated an email confirming that “There will be no monument recognizing this individual.” The Progressive carried the news of the cancellation. This, while the walls of (and around) the Genocide Museum in Vilnius continued to be plastered up with posters celebrating the “2018 Year of Ramanauskas.”

Now 2018 is a very special year for Lithuania. It is the 100th anniversary of the rise of the modern democratic state in 1918, special too for its remaining Jewish people, because that state was founded on the principle of cultural autonomy for minorities. It included even a Jewish Affairs ministry led by the famed Dr. Max Soloveitchik in its early years. Ramanauskas’s link to those events? He was born in 1918 (as were so many others). After deliberation with numerous colleagues in different fields here, our small dissident band at Defending History countered by naming as person of the year for 2018 Malvina Šokelytė Valeikienė, who was decorated by the Republic of Lithuania for her bravery in Lithuania’s 1918 war of independence, and then went on during the Holocaust a generation later to save a Jewish neighbor. The point we were making by doing this was honoring a true Lithuanian hero in honor of the country’s 100th anniversary celebration, and, of course, making a wider point: Lithuania, like all the countries of Eastern Europe, has many centuries of genuine heroes in whom all humanity can rightly take pride.

Addition of a Holocaust Cubicle in the Basement

Following a number of Holocaust-related scandals, not least the attempts by Lithuanian prosecutors to target Holocaust survivors for investigation of their activities in the Jewish partisans, which I reported on for Tablet back in 2010, the Genocide Museum announced with considerable PR gusto that one of the former prison cells in the basement would be turned into a Holocaust exhibit. It was opened with fanfare in 2011, in the atmosphere of a “major concession to the Jews.” Yes, you heard that right, the “concession” was that the Holocaust would finally merit one cubicle in the basement of the city’s Genocide Museum.

Although a map of the basement still lists the same 18 exhibits as before, including cell no. 3 (= item no. 5 on the list, “marks on the wall made during the Nazi occupation”), it suddenly came to house a contemporary museum-tech exhibit on the Holocaust. There is an emblem of the yellow Star of David outside the door and when you look inside the new room, there is a huge Star of David on the far wall near the radiator.

The problem with this one room addition is that it tells a very distorted story of the Lithuanian Holocaust. Worst of all, the perpetrators who unleashed the killing through much of the country before the Germans even arrived, the LAF and their associated killer groups, is obfuscated yet again. The Nazi puppet prime minister of the summer of 1941, Juozas Ambrazevičius (Brazaitis) whose remains were repetriated in 2012 from another Connecticut town, Putnam, for reburial with full honors in Lithuania, is presented as obliquely “anti-Nazi” when in fact he personally signed Lithuanian versions of the Nazi orders for Jews from his own city, Kaunas, to be sent to a murder camp, the Seventh Fort, and another for all the remaining Jews to be locked up in a ghetto within one month.

In other words, the added “Holocaust Room” repeats the same Fake History as in the main grand exhibit halls upstairs: covering up the murders by the LAF, and of the Provisional Government which followed it, at the start of the Lithuanian Holocaust, and sanitizing the perpetrators as some kind of freedom fighters.

Much of the Holocaust room is dedicated to the Vilna Ghetto, where it is infinitely easier to downplay local collaboration and consider it all a German deed alone, with a few odd tantalizing references to the Jewish police and Judenrat as the supposed co-authors of the Holocaust in Vilna. While far from noble in many cases, there is no moral comparison of the tragic compulsion of Jewish police and Judenrats intermingled with false hopes of saving some, vs. the massive voluntary participation in the gleeful genocide of neighbors by those in positions of power. To cite the one and omit the other amounts to Fake History par excellence.

But there is one major redeeming feature of the Holocaust cell in the basement: There is honor for those who did the right thing and saved a neighbor from the barbaric hands of the Nazis, and their LAF and other local collaborators and partners. They are the true Lithuanian heroes of WWII. They deserve an entire museum in their honor.

In addition, there have been some other welcome modifications since 2011. Some Holocaust videos have been added to the repertoire on the monitors, and the outside plaque now duly notes that the building once housed the Gestapo.

Chicanery, Context, Caveats

The nonsense of Fake History museums rises to the level of dangerous chicanery only when it is all done so well that is can fool even journalists from famous Western publications. In recent years, naive souls writing for the New York Times (in 2015) and the San Francisco Examiner (2016) were successfully bamboozled, and the front desk where you pay to buy your ticket has stickers flaunting the approval of those publications for the farce of historical denialism inside. By contrast, a well-seasoned author from the London Guardian, writing back in 2008, immediately saw that something was wrong, and another, in 2010, analyzed the Double Genocide industry. The New York Times’s seasoned, Pulitzer Prize-winning foreign correspondent Rod Nordland recently did some measure of penance for his publication by writing an extended, fair article after a chance visit brought him to this shocking museum, and to some other shocks of contemporary Vilnius. These include church steps made of readable Jewish gravestones that the church has refused to remove for years, and plans to house a new national conference center in the heart of the old Vilna Jewish cemetery (reported by Tablet in 2017).

Today’s Putinist Russia does indeed pose a very real and serious threat to the small, freedom-loving nations on its periphery, most dangerously the three Baltic states, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, which were forcibly made into Soviet republics for all those decades, not left as Warsaw Pact “allied states” like Poland, Czechoslovakia, or Hungary. The Western alliance, NATO, the European Union and Western civilization more generally need to stand up for these democracies against Putin’s (and future Russian) mischief, and make clear that the protections of NATO are real and permanent. But that loyalty must not include adopting a pro-fascist revision of history that turns Holocaust perpetrators into heroes simply because they were “against the Soviets.” Just about all East European Holocaust collaborators and perpetrators were “against the Soviets.”

Adulation of Hitler’s accomplices is at odds with core Western values as is the legal crackdown, of all things, on dissident opinions about history. It is shameful that in 2017, to counter Putin’s disgraceful “Zapad 17” military exercises right near the borders of his small, free neighbor countries, NATO produced a film lionizing the Forest Brothers without so much as a hint of a second opinion that these were largely veterans of Hitlerist fascism and mostly murderers of civilians and believers in an ethnically pure state. In recent years, American embassies in this part of the world, particularly here in Vilnius, have misguidedly participated in events to deceive foreign (particularly Jewish) groups while participating themselves in the defamation of any who challenge Baltic history revisionism as “Putinist agents.” The noticeable shift in State Department policy can be traced to 2009-10.

True friends of the Baltic states should be pointing out that such museums do grave damage to the country’s reputation and that those citizens who stand up with a contrary opinion should not be the victims of state-financed campaigns of defamation or prosecutorial investigations carried out to harass dissenters and deter free thought. The USSR, during the time of the Lithuanian Holocaust (1941-1944), in alliance with Great Britain and the United States, was the only force seriously fighting the Nazis and was largely responsible for there being any survivors and progeny alive today. History is history.

Still, there is a very big caveat to all this. People reading such articles might think that Lithuania is an anti-Semitic country or a country with a majority of fascism-lovers who delight in the Holocaust having taken place. Nothing could be further from the truth. I have lived for almost 19 years here in the Lithuanian capital Vilnius, where I have always felt welcome, well-treated, and blessed to have a wide and diverse circle of friends from an array of backgrounds. Here’s that extra bit of proof: I am treated very well by the fine staff whenever I enter this museum that makes my local Jewish friends sick. When I bump into its director at a weekly antiquarian flea market that we both frequent, we exchange warm handshakes and pleasantries. This is not personal.

As in other parts of Eastern Europe, a small group of powerful elites, who have been able to enmesh Holocaust history into current geopolitical security, are the ones doing the damage to history, and to the freedom of their own citizens and the reputations of their own countries. History will show that the folks they are prosecuting under a series of laws are the real patriots. While there certainly is an anti-Semitic component in elite ultranationalist circles in this part of the world, it is neither pervasive nor necessarily dominant. There is moreover a special kind of East European anti-Semitism that is focused on an alleged Jewish Communist past, that despises today’s tiny remnant Jewish communities who have a different narrative of history (think Charlottesville), but that has generally very positive approaches to modern Western Jews and Israelis. There is a heavily subsidized effort to enmesh Judaic studies (and particularly its fragile components like Yiddish studies), and even Holocaust Studies per se, within the project to revise the narrative of the Holocaust and WWII.

Future of the Museum

If any one feature of this museum is just “too much,” it is its name. This past September, an announcement was made that national powers had decided to change the name to: “Museum of Occupations and Freedom Fights.” Last month, the nation’s parliament took steps to enact the name change. As of now, the bill is one ballot short of adoption.

But in a macabre sort of way the new name is worse. The inflation of the concept “genocide” to cover Soviet crimes in Lithuania (and to obfuscate the Holocaust) is lost. But what is gained? The misnaming, potentially in the museum’s very title, of the murderous unleashing of the Lithuanian Holocaust by the LAF Hitlerist fascists as a freedom fight! Is that what is supposed to count as an improvement?

And so, without the name change, and even more so with the proposed name change, the shameful core of this museum is its permanent exhibit’s glorification, via fake history, of actual Holocaust killers who unleashed its first phase here in June 1941, turning them into would-be rebels and freedom fighters. That falsification needs to disappear before the next million visitors are misled. This is all a grave injustice to the delightful, hard-working, tolerant, and economically long-suffering citizens of the country, who all deserve better. Until that most foul of untruths about the Holocaust is done away with, this will remain the most dishonest and pernicious museum in the lands of NATO and the European Union.

***

Yom HaShoah, or Holocaust Remembrance Day, is observed in Israel and around the world on 27th day of Nisan, which falls on April 11-12 this year.

Dovid Katz, a Vilnius-based Yiddish and Holocaust scholar, is professor at Vilnius Gediminas Technical University. He edits the web journal Defending History and is at work on a new Yiddish Cultural Dictionary.