Lore Segal’s Warm and Weird ‘Tell Me a Mitzi’

The 88-year-old award-winning author wants her children’s classic back on bookshelves

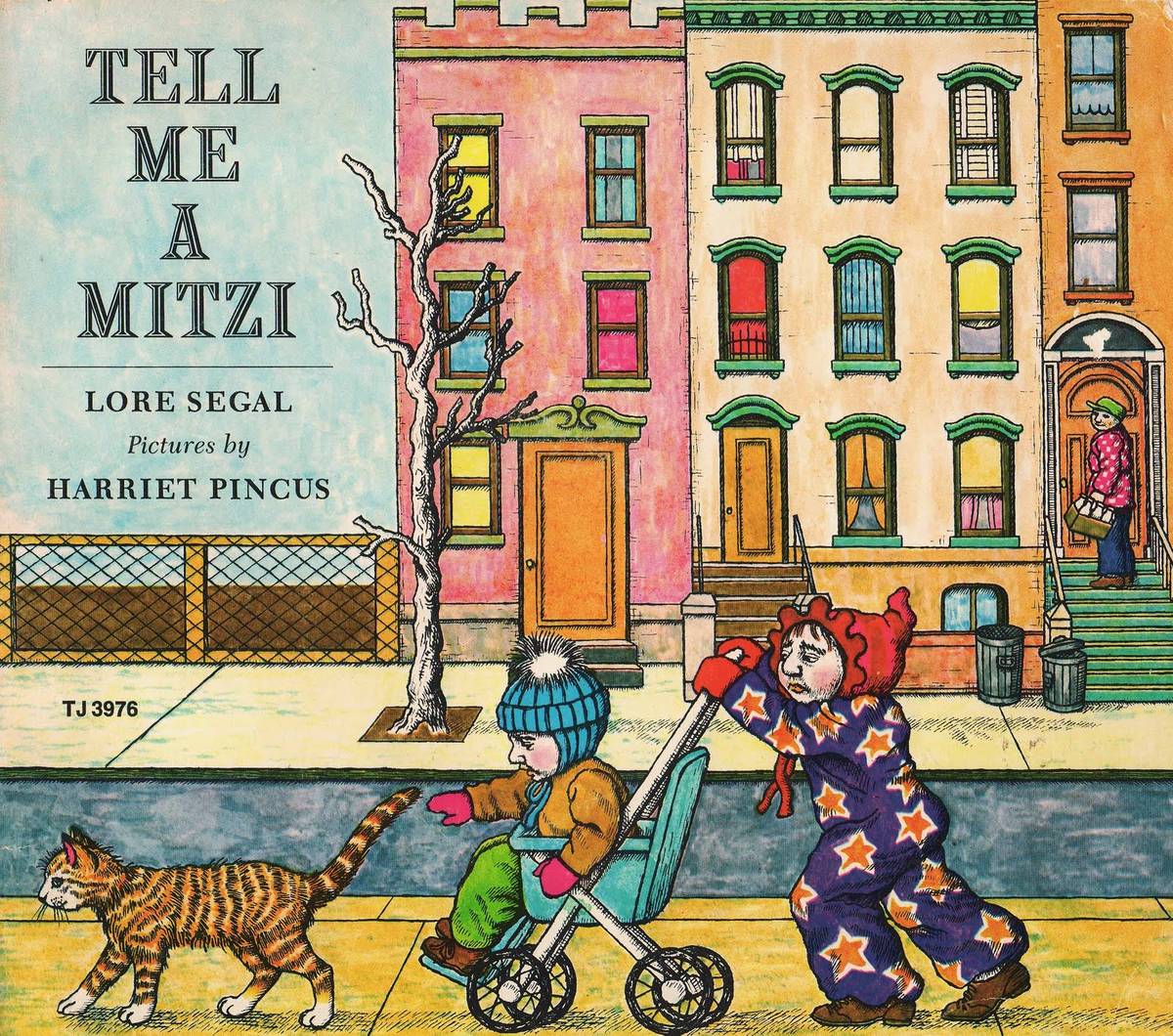

As a child I was obsessed with Tell Me A Mitzi, originally published in 1970 and in print at least through the early 1990s. (Even the author isn’t sure when it disappeared from shelves.) It is a deliciously weird book. Booklist, in a starred review, called it “captivating” and noted its mashup of fantasy and reality, naturalness and warmth. “The illustrations [by Harriet Pincus], so filled with details and surprises they invite repeated scrutiny, have verity and vitality, poignancy and endearing humor,” the review astutely says.

I bought a used copy for my own kids nearly a decade ago, and they were just as enthralled as I was. But why?

Tell Me a Mitzi is actually three stories—Mitzi Takes a Taxi, Mitzi Sneezes, and Mitzi Meets the President—in one. Mitzi, a little girl living in a neighborhood of tenements and walk-ups that could be the Lower East Side or Brooklyn, could be the 1940s or the 1970s, has a series of low-stakes yet somehow compelling adventures.

In the first, she decides to put her baby brother in a cab and visit their grandparents. Alas, she doesn’t know their address, and the cabbie deposits Mitzi and Jacob back onto the sidewalk. In the second, everyone in Mitzi’s family gets sick, and chicken soup is deployed. In the third, Mitzi attends a parade, meets the president (who looks remarkably like Richard Nixon), and receives some much-yearned-for chewing gum.

Pincus’s illustrations, frankly, are hideous… but also alluring! One critic compared her work to that of cartoonist R. Crumb, and noted the “whimsical grump” in the characters’ faces. I think her pictures are Sendakian, but way less cute. The kids have squinched-up faces and old-man noses. Their New York City is crowded and bright and dense and stuffy, yet utterly beguiling.

The book is fun to read aloud, with jazzy rhythms and rat-a-tat-tat, deadpan dialogue:

Mitzi said, ‘I’m hungry for some gum,’ and Jacob said, ‘Me too,’ and their father said, ‘I don’t have any.’

‘Well I want some,’ said Mitzi.

‘Me too,’ said Jacob, ‘And I want a parade.’

‘Well, I don’t have one,’ said his father.

‘Look in your pocket,’ said Mitzi.”

Segal is 88 years old now, living on the Upper West Side. I’d known her work only through my narrow, narcissistic child’s lens, but a quick Google search told me of my cluelessness. She was born in Vienna to upper-middle-class Jewish parents in 1928, and escaped from the Nazis on one of the early Kindertransport trains in 1939. (Her family’s experience was featured in Into the Arms of Strangers, which won the Academy Award for best documentary in 2000.) In England, she learned a new language in a matter of weeks and campaigned tirelessly to get her family out of Austria, writing letters to the Jewish Refugee Committee and British authorities. On her 11th birthday, she was reunited with her parents. But they’d made it to England on domestic servant visas, and Lore had to go live with various foster families. She turned that experience into her first novel, Other People’s Houses.

She wrote many more books. Of Her First American (1985), The New York Times wrote: “Lore Segal may have come closer than anyone to writing The Great American Novel.” Her 2007 novel Shakespeare’s Kitchen was a Pulitzer Prize finalist, and she’s won a Guggenheim Fellowship, a grant from the National Endowments for the Arts and Humanities, and several O. Henry Awards for short stories. Over the years, she’s collaborated with a veritable who’s who of American children’s book illustration: Maurice Sendak, Rosemary Wells, James Marshall, Paul O. Zelinsky, Sergio Ruzzier. She was married to an editor at Knopf and they had two children together, but her husband died nine years after the wedding. She’s taught writing at Princeton, Columbia, Bennington and Sarah Lawrence, and still teaches at the 92ng Street Y.

Tell Me a Mitzi, which began as a story for Segal’s own kids, feels resonant for today’s free-range parents. Mitzi wakes up early, gets her baby brother fed and dressed, packs up their stuff and goes out to have an adventure. She has no idea what she’s doing. But nothing bad happens, and adults help her out. I asked Segal whether she’d raised her own kids to be as independent as Mitzi. She laughed. “When my daughter was in high school, she went with Amigos de los Americas to Mexico to help people. Recently she said, ‘How could you let me go? I would never let my kids go!’ Well, at 10 years old I was traveling from Vienna to Liverpool to London and I wasn’t aware it was unusual. I am an anxious person. I assume the world is really a rotten place most of the time. I think it’s always been rotten and always will be. But I think it’s so interesting. So you’d better just live!”

Maurice Sendak put Segal and Pincus together. “Harriet was in her late 30s, from Brooklyn,” Segal recalled. “She had gotten polio on her 16th birthday and was in a wheelchair. She lived with her parents in incredibly confined circumstances, and he used to visit her. I adored her. She died of complications from polio.” Segal instantly loved Pincus’s illustrations, though they were strange and vintage-y and didn’t depict the Upper West Side she knew. “You have a doorman in a fourth floor walkup!” Segal exclaimed. “I think this is dream stuff! I think this is some kind of magic!”

The illustrations were controversial even back then. “Farrar Straus had an inquiry from a French children’s publisher who said they wanted to publish it in France, but didn’t want to use these illustrations,” she said. “I don’t know how much was said and how much I intuited, but it was my clear impression that they were saying ‘These are shtetl Jews’… and they are.” Segal would like to find a publisher for the out-of-print book, but only if she can keep Pincus’s artwork. “I am tremendously loyal to her,” she says.

The book feels Jewish without having any Jewish content. “It doesn’t talk about Purim or the Holocaust,” Segal told me. “But we have thumbprints…and you can tell this book is Jewish by its thumbprint. The way one looks, the way one thinks about things – it’s nothing specific. I have a beloved Irish daughter-in-law, and we have the same politics, but we eat differently and speak differently and we have different thumbprints. It is who you are, without setting out to be particular. There’s no way to explain that. The introduction to each story, the lines in which someone begs, ‘Tell me a story”…it’s not explicitly Jewish. It just feels like home.”

Previous: ‘All-of-a-Kind Family’ Series Getting Reissued

Related: We Are Family

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.