The Manila Poker Group That Rescued German Jews

Little-known efforts led to the Philippines saving over 1,300 German and Austrian Jews from 1938 to 1939

Vu Ahin Zol Ikh Geyn?

Tell me where shall I go,

Who can answer my plea?

Tell me where shall I go,

Every door is locked to me?

Though the world’s large enough,

There’s no room for me I know,

What I see is not for me,

Each road is closed, I am not free—

Tell me where shall I go.

Written in the 1930s by the Polish Yiddish actor Igor S. Korntayer, this plaintive Yiddish ballad describes in stark terms the dilemma faced by German Jews desperate to escape from their homeland after Hitler came to power. Suffering through a worldwide economic depression, Western nations, including the United States and Canada, imposed stringent immigration laws and rigid quotas and were unwilling to accept large numbers of refugees. In order to better identify German Jews who tried to enter the country, the Swiss government asked the German government to stamp a large red “J,” for “Jude,” in the passports of all German Jewish citizens. Thwarted from emigrating to the West, thousands of German Jews fled eastward by sea and land routes seeking refuge in Asia and the Far East, especially the open city of Shanghai.

Shanghai was unique in that the city was internationally controlled and required neither a visa, passport, affidavit, nor certificate of guarantee for entry. Jews desperate to leave Germany and who were able to do so found asylum in Shanghai. The outbreak of war between China and Japan in 1937 made immigration perilous. In September 1937, Germany sent a ship to Shanghai to evacuate its nationals from the war zone and bring them to Manila. They also took on board 28 German Jewish families. When the ship arrived in Manila, the city’s small Jewish community took charge of the Jewish refugees. This episode became the impetus for a Philippine plan to rescue German Jews from Nazi clutches.

Of all the Far East sanctuaries, only one country deliberately sought to save Jews: the Philippine Commonwealth. The rescue plan evolved from the close friendship and cooperation of a small group of men who regularly met to play poker. Their efforts led to the Philippines saving more than 1,300 German and Austrian Jews from 1938 to 1939.

The story begins with the four Frieder brothers, Alex, Phillip, Herbert, and Morris, who owned a two-for-a nickel cigar business. In 1918, the brothers decided to transfer their cigar manufacturing operation to Manila from New York City, to reduce production costs. The brothers then took two-year turns living in Manila and overseeing their plant. They also became active in Manila’s Jewish community of 150 men, women, and children.

When the Shanghai German Jewish refugees disembarked in Manila, American High Commissioner Paul V. McNutt waived the visa requirements and admitted them. At his urging, Alex and Phillip Frieder organized a Jewish refugee committee to support and help them adjust and settle in. From these refugees, the Frieders heard harrowing accounts of Nazi brutality and atrocities perpetrated against Germany’s Jews. This revelation spurred them to rescue German Jews. To achieve their goal, the Frieders enlisted the help of men they played poker with. These poker buddies included McNutt, Manuel L. Quezon, president of the Philippine Commonwealth, and a young Army colonel named Dwight D. Eisenhower, then an aide to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, field marshal of the Philippines. At the late-night card games, these friends devised a rescue plan to eventually bring as many as 10,000 German Jews to the Philippines.

Although American immigration laws applied to the Philippines, the country had no quota system. A financial guarantee from a resident sufficed to obtain an entry visa. If the Jewish refugee who arrived in the Philippines was able to find employment, he met an important provision of U.S. immigration policy: that he not become a burden on the state. McNutt, the Frieder brothers, and Quezon became the active movers of the plan; Eisenhower played no ongoing role in the rescue but served as the group’s liaison to the U.S. Army, which oversaw the Philippines.

Paul V. McNutt, a Roosevelt appointee, had been a professor of law, governor of Indiana (1935-1937), and a prominent figure in the Democratic Party. A decent and humane individual, McNutt learned about the Nazi atrocities from Jacob Weiss, a close Jewish ally in Indiana’s Democratic Party, and from reports he received from Jewish groups. McNutt had long disdained racial hatred and anti-Semitism, and respected Jews, as he said, “for their toughness, resiliency, and success.” He often spoke out and condemned the German government and Hitler, and supported the Zionist goal of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. McNutt realized that any long-term effort to permit large numbers of Jews to enter the Philippines had to be methodical, carefully planned, and in accord with United States immigration statutes.

McNutt acted cautiously because he wanted the plan to succeed. He felt the integration of the first groups would determine the number of those able to follow. He assured Jacob Weiss and the Frieders he would do everything in his power to absorb a portion of the Jewish political refugees from Europe. To follow through, he collaborated with Quezon, the other crucial member of the poker group.

Quezon, the Philippine president, enthusiastically supported the plan. In 1935, Filipinos had elected him as the commonwealth’s first president. At the time, the Philippines were still a colonial possession of the United States. Quezon was an astute politician who used his fluency in English, political acumen, and gift of flattery to win over policymakers in Washington. Most important, Quezon was friendly and socialized with McNutt and the Frieders and visited with them at their homes. As a non-Aryan, he hated the Nazis and sympathized with the plight of Jews in Nazi Germany. He also believed the Jewish refugees would become an asset to the Philippines, especially with their expertise and knowledge of medicine and other professional fields. His endorsement proved significant because the commonwealth’s officials determined who could get off the ships and enter the territory.

The plan the men devised respected U.S. immigration laws and gained for the Philippines occupations and skills needed in their economy. McNutt told Phillip Frieder that if the Jewish community in Manila assumed responsibility for the immigrant families, he would be glad to allow them to enter. He said it was of the utmost importance that the refugees sent to the Philippines be unlikely to become public charges and able to easily assimilate into the community. Frieder agreed, provided that he and other Jewish members of the community could select the type of people who were to come.

The Frieders and other Jewish leaders worried that a large influx of refugees would tax the employment market and necessitate extensive welfare services, which their tiny community was unable to provide. They also knew that the long-term success of any resettlement program required the sympathy of the Filipinos. That meant the refugees had to be integrated into the community, secure employment, and avoid becoming public charges. Consequently, they advocated a controlled-entry program.

With McNutt’s consent, the Frieders contacted the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). The JDC had created the Refugee Economic Corp. (REC), which helped resettle Jewish refugees. The REC worked with the Hilfsverein der Juden in Deutschland (Relief Association of German Jews). This German Jewish organization had been established in 1901 to engage in social welfare and educational activities among needy Jews. After Hitler came to power, the association assisted German Jews trying to emigrate everywhere but Palestine, which was handled by the Jewish Agency.

The Hilfsverein kept lists of those German Jews who applied to emigrate. The lists included the occupation or profession of each prospective emigrant. The German government allowed the Hilfsverein to exist because it wanted all Jews out of Germany, and the Hilfsverein promoted this goal. After the war broke out, the German government shut it down and assumed its activities.

The Frieders submitted the list of occupations they felt the economy needed and whose practitioners could be absorbed into the Philippine community to McNutt who, as the American High Commissioner, was a key link between the Frieders and the REC. He sent the plan and the list of prospective occupations to the REC. The list contained 14 needed skills and occupations as well as the number of people to be admitted in each category. Most of the occupations were in medicine—doctors, dentists, and nurses. Other categories included chemical engineers, auto mechanics, agricultural experts, cigar and tobacco specialists, men and women barbers, women dressmakers and stylists, accountants, film and photography experts, and even one rabbi, “not over 40 years of age, Conservative, married, and able to speak English.”

The REC and JDC approved the plan and transmitted the list of immigrants to the Hilfsverein. The REC in conjunction with the JDC also advanced funds to support the immigrants. This met with McNutt’s stipulations that the immigrants not become public charges. The REC asked the Hilfsverein to “prepare a preliminary list of the people meeting the requirements outlined” in the REC list, and to select from among the applicants for emigration those who might be “absorbed in the Philippine Islands within a short time.” It reminded the Hilfsverein that “in view of the delicacy of the negotiations involved, we expect you to keep this matter entirely confidential, and under no circumstances give it any publicity whatsoever.”

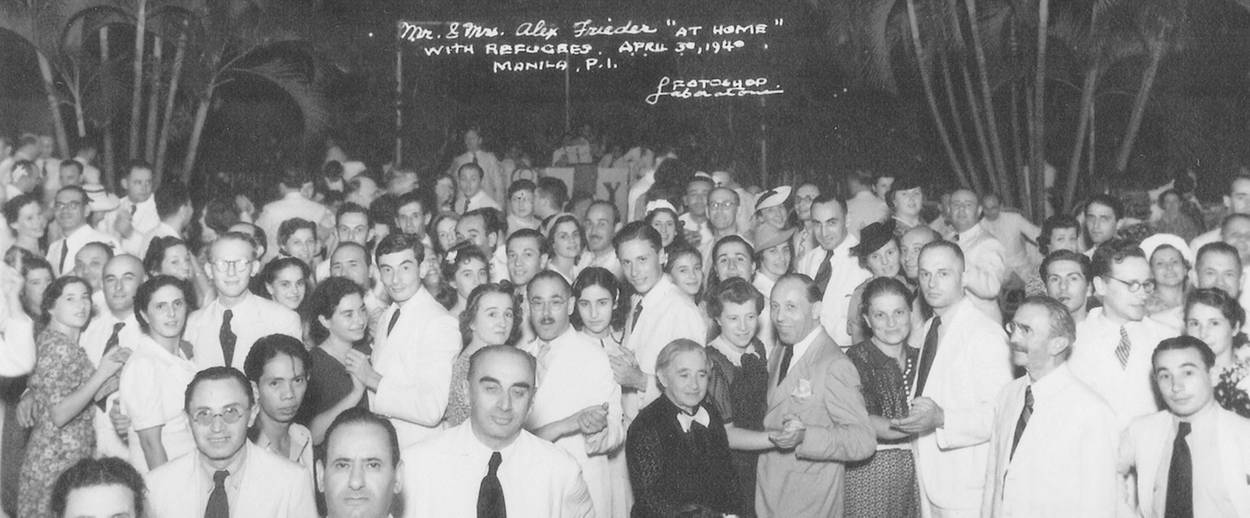

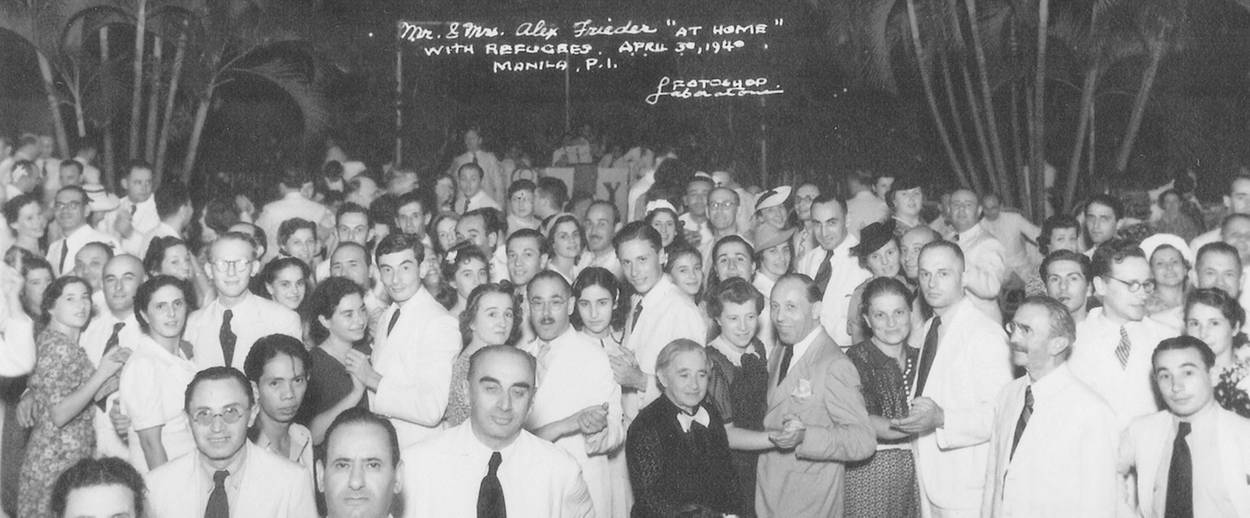

The REC worked with the Hilfsverein to determine who among those on the list should have the first chance to leave. The Hilfsverein informed the chosen applicants, got their OK, and sent their dossiers, which included photographs, curriculum vitae, educational data, and letters of recommendation to the REC and to the Jewish Refugee Committee in Manila. Alex Frieder and other members of the committee carefully studied the applications and forwarded the names to the Philippine government for approval. Alice Weston, Alex Frieder’s daughter, remembered that “day after day” her father pored over lists of would-be refugees. She claimed it took so much of his time that he neglected his own business.

Seeing that the refugees were unlikely to become a public burden, McNutt endorsed visas for the German Jews who had the desired occupations and passed the screening process and background check. He relayed this request to the State Department’s visa division, which sent instructions to the appropriate U.S. consular officers to issue the visas. The State Department forbade consular officials from granting visas to any refugee except those accepted by Manila’s Jewish Refugee Committee.

McNutt’s role cannot be overstated. He was the prime mover in fostering a dialogue between the Philippine government, the U.S. State Department, the Manila Jewish community, and the REC. His willingness to be personally involved and to work with the various agencies was crucial to the plan’s success. In a letter to McNutt, Charles Liebman, president of the Refugee Economic Corp., wrote that his organization sincerely appreciated “the most generous way in which you have interested yourself in the fate of the refugees.” Alex Frieder later wrote that without McNutt’s involvement and assistance, they would not have succeeded in saving Jews.

The refugees who came to Manila had a difficult time adjusting. They did not know the language; the heat and humidity were overpowering; and the mosquitoes were gigantic. Many lived in crowded community housing, which led to tensions and fights. But the young Jews saw the Philippines as a new adventure. Children climbed mango trees, swam in the bay, and learned Filipino songs. Lotte Hershfield remembered running around in sandals and summer clothes, but “it was very difficult for my parents,” she said. “They never really learned Tagalog [the official Philippine language]. They had been Westernized and they stayed mostly within their circle of other immigrants.”

Although many of the refugees found suitable employment, some did not seek work because they were elderly and supported by relatives living abroad. Others were not able to work in their professions or trades because the market in those fields was oversupplied. Numbers of refugees also overstated their qualifications when they had registered for emigration with the Hilfsverein. Alex Frieder admitted that perhaps “we have been misled by the rather indiscriminate usage of the terms “perfect,” “expert,” and “specialist” on the affidavits, and thus have given visa recommendations to cases for which we have been unable to find employment after arrival in Manila.” In addition, he said, “the fact must be faced that a certain number of our immigrants will never make adjustments,” and will need relief permanently.

After America entered the war and Japan invaded and occupied the Philippines, the granting of visas to Jews ended. Ironically, the Japanese treated the German Jewish refugees considerably better than the British, American, and other enemy nationals residing in Manila. Because Germany was Japan’s ally, they thought of the German Jews as Germans and did not put them in internment camps. However, Jewish nationals from countries at war with Japan were interned and treated badly.

When the U.S. began to reconquer the Philippines, conditions for Jews quickly deteriorated. As the Japanese suffered defeat, their troops in Manila went on a rampage. They committed widespread atrocities against everyone, including the Jews, before they retreated from the city. The Japanese shot and bayoneted anyone and everyone they considered American and their allies, which in their eyes included almost everyone who was white.

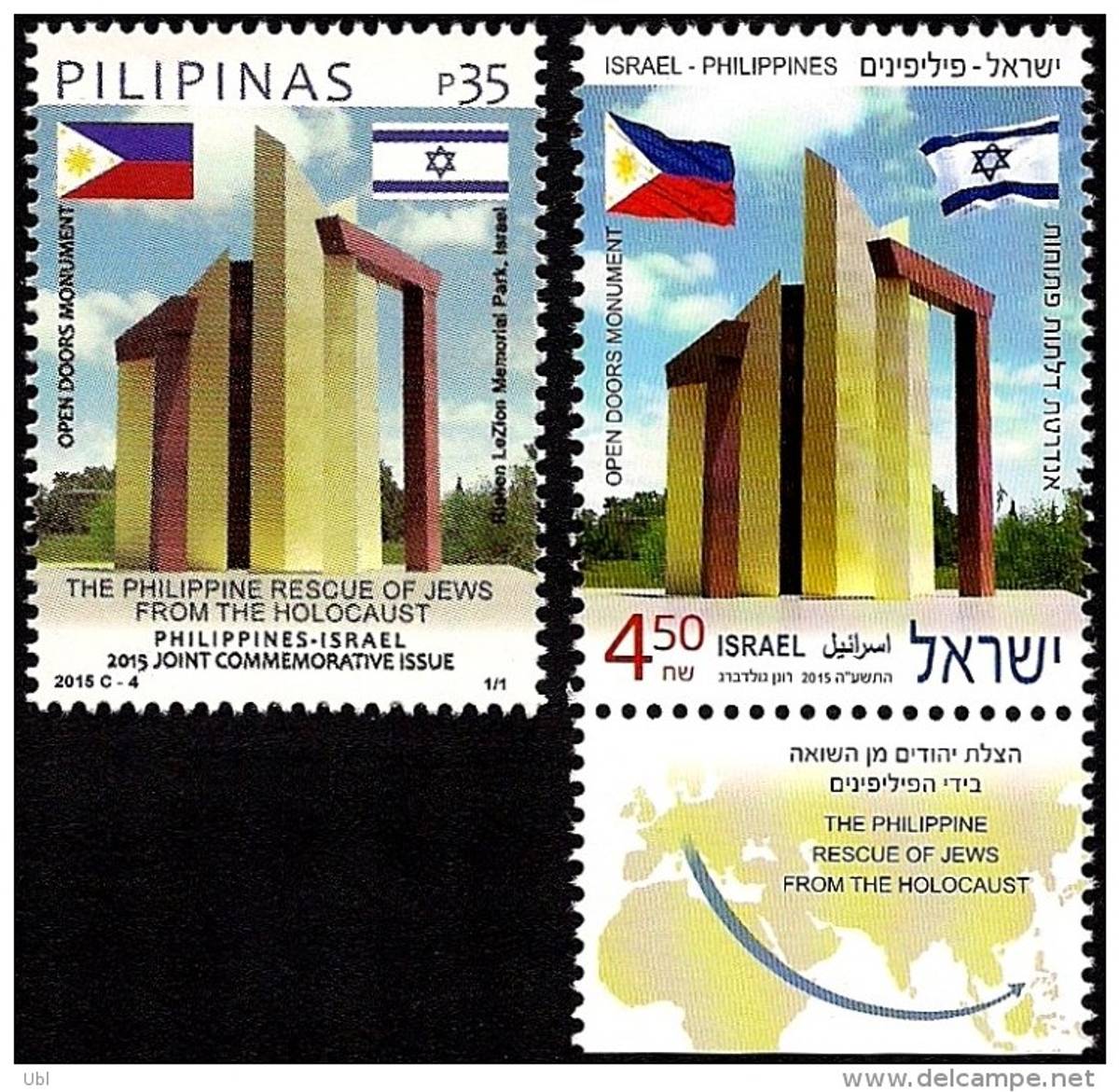

Despite all they endured, the hundreds of surviving Jews and their children remained forever thankful that the Manila poker players saved them from certain death in the Holocaust. A recent documentary, Rescue in the Philippines, chronicled the affair. And in 2009, the Israeli city of Rishon Lezion erected a monument shaped like three open doors honoring Manuel Quezon and the Philippine people for their noble actions in rescuing German and Austrian Jews from persecution and death.

The article is based on correspondence, memos, and reports about the Philippine rescue operation housed in the archives of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee. Copies of this material can also be found in the Yad Vashem archives in Jerusalem. Other source material included interviews with survivors, Dean J. Kotlowski’s biography of and articles about Paul V. McNutt, and Frank Ephraim’s 2003 memoir, Escape to Manila: From Nazi Tyranny to Japanese Terror.

Robert Rockaway is professor emeritus at Tel Aviv University, and the author of But He Was Good to His Mother: The Lives and Crimes of Jewish Gangsters. Maya Guez is a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer in Tel Aviv University.