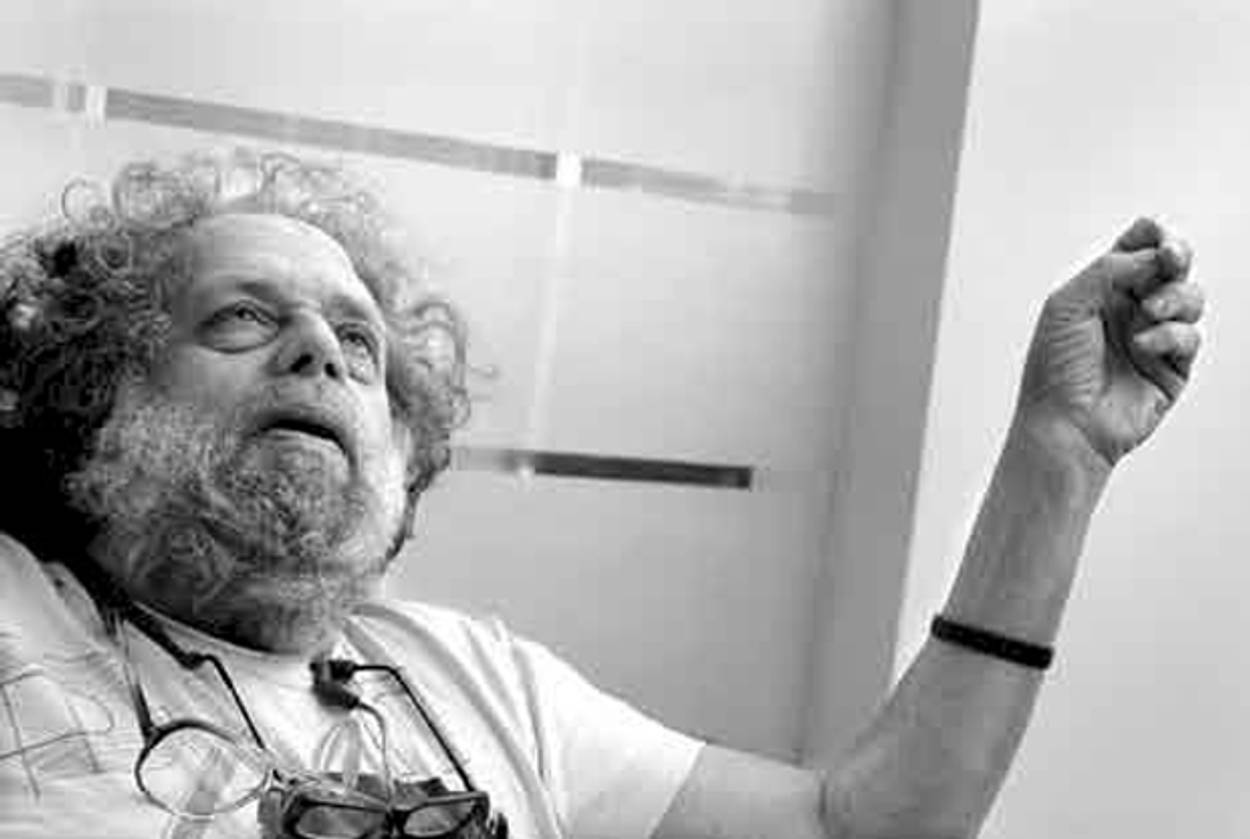

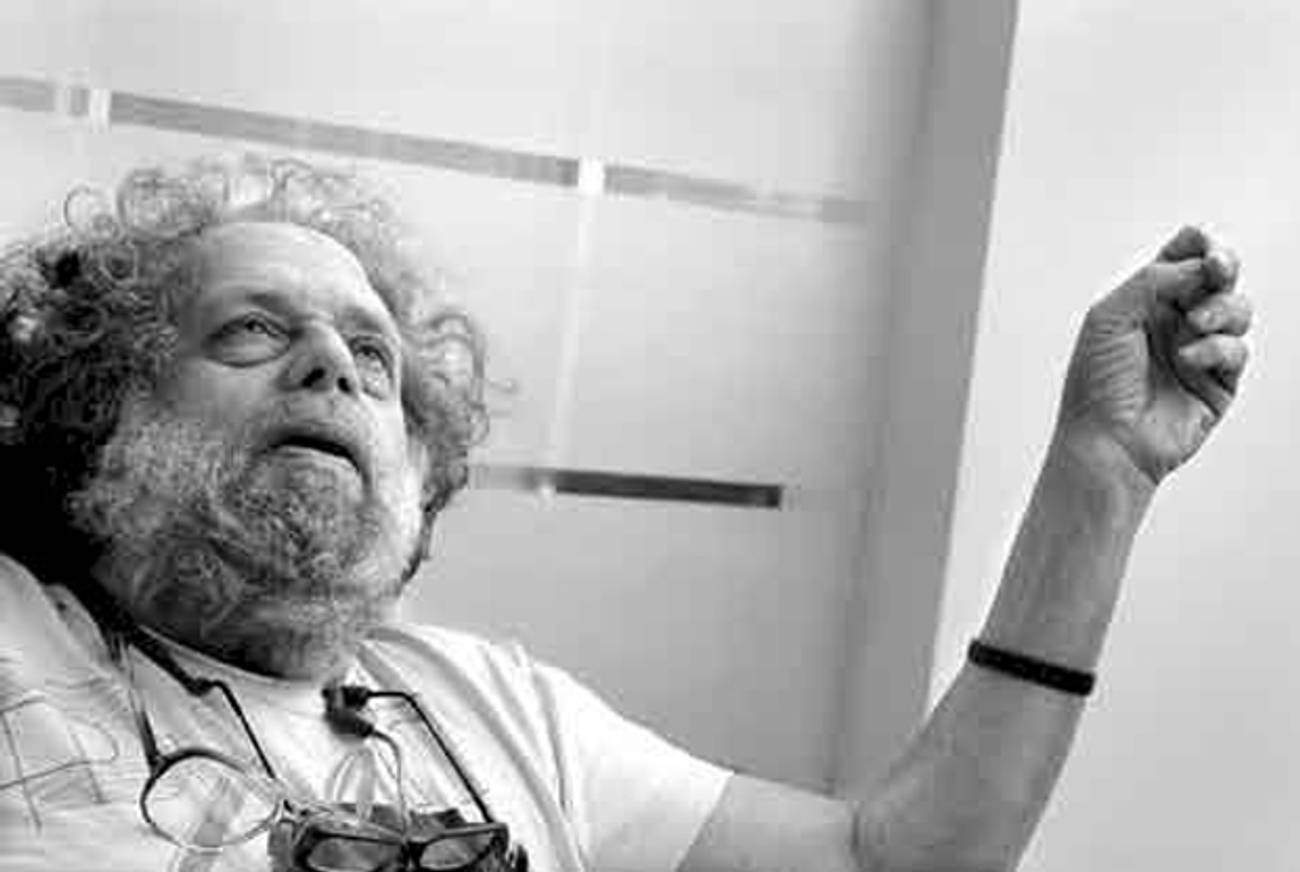

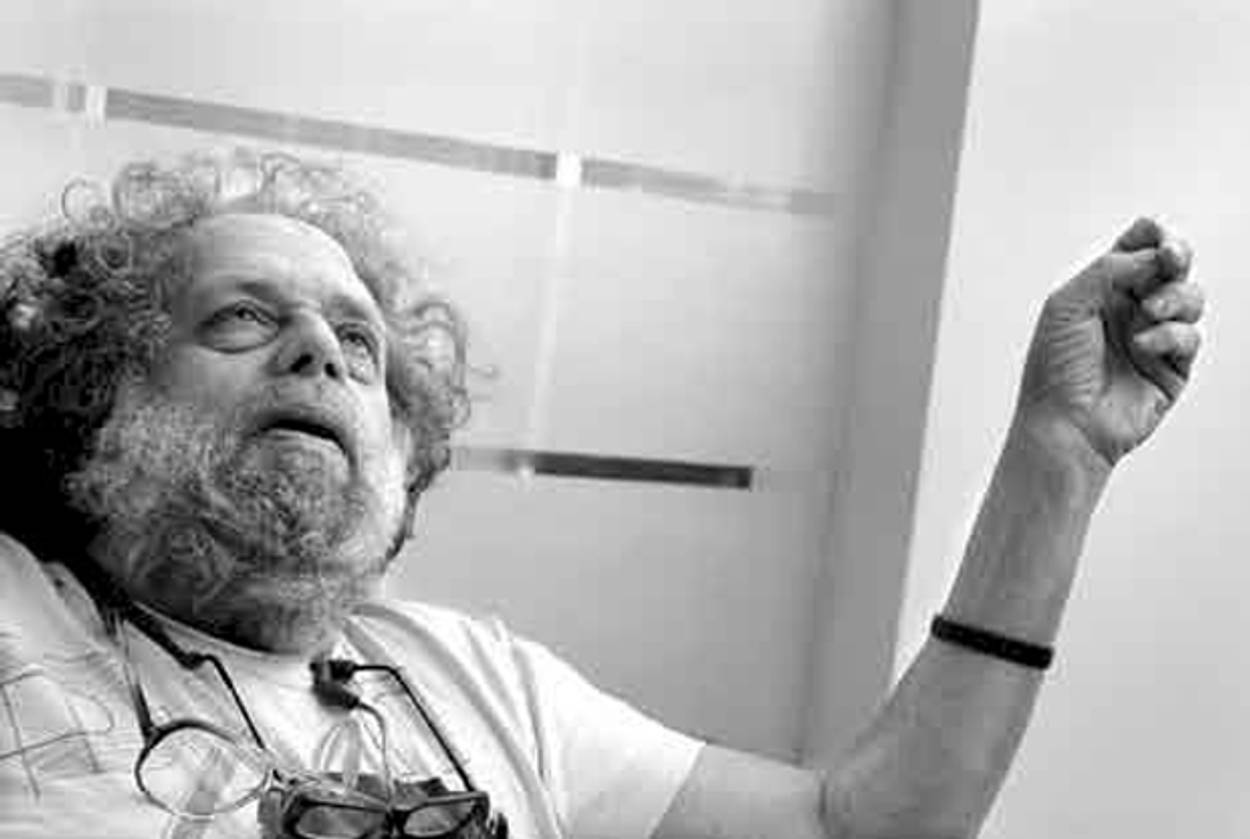

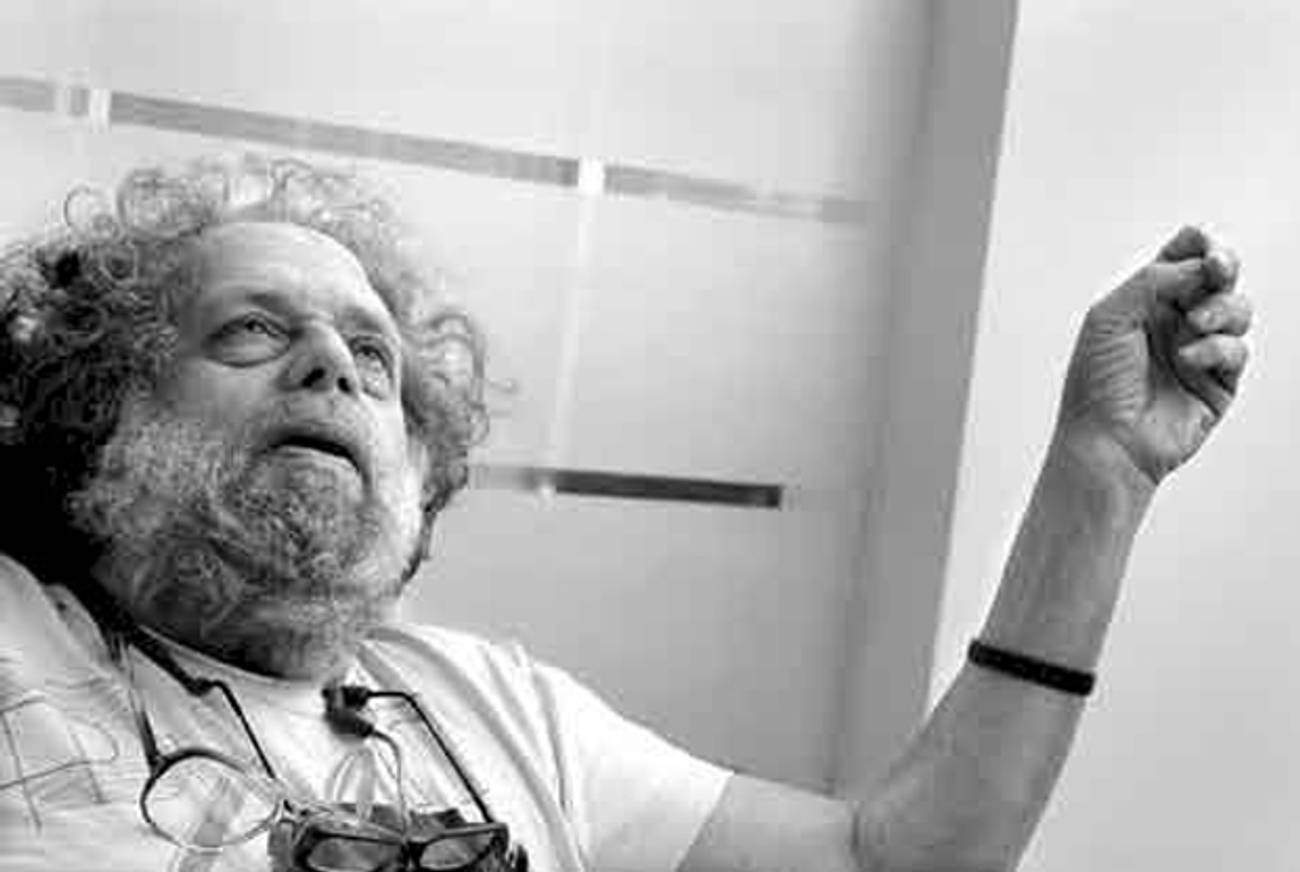

Marshall Berman, Marxist Humanist Mensch

Remembering the author, who died yesterday at 72

The cover of his 1999 essay collection, Adventures in Marxism, containing twenty years of his essays, depicted a cartoon of the full-bearded Marx, stubby arms flailing, one hand in a fist, the other, waving, in a mid-jamboree dance step like some sort of hybrid of hora and kazatzka. Change the face from Karl Marx’s to Marshall Berman’s (as bushy-bearded as big-craniumed as Karl’s, but warmer-eyed) and you’d have a logo for the collected works of Berman, bear-like sage of the Upper West Side, who was often found on the street wearing a T-shirt bearing the visage of Marx or Nietzsche, and who could explain to you with great flair why you were mistaken if you thought those two 19th-century guys were not a dynamic duo.

Characteristically, Marshall introduced those twenty years of essays on Marx with a story about his father, who made his living in various garment industry jobs, then wrote and sold ads at Women’s Wear Daily, which led him into a failed magazine start-up from which his partner took the money and ran. This story led to a riff on the brutality of cutthroat capitalism. The personal was political. From there, he hastened to Marx, but not Marx the prophet of surplus value and the expropriation of the expropriators; rather the Marx who was “part of a great cultural tradition, a comrade of modern masters like Keats, Dickens, George Eliot, Dostoyevsky, James Joyce, Franz Kafka, D. H. Lawrence (readers are free to fill in their personal favorites) in his feeling for the suffering modern man on the rack.” Leave it to Marshall Berman to swing from the garment district (where the rack was literal) to Marx’s Economic-Philosophical Essays of 1844 (where he rightly celebrates Marx’s “feeling for the individual”) in fewer pages than it would have taken Marx to amass factory inspector reports or to clear his throat going after Hegel hammer and tongs.

What Marshall will likely be most remembered for—and deservedly—was his visionary 1982 book All That Is Solid Melts into Air: The Experience of Modernity. This was truly a revelation, an evocation and sometimes a prose-poem with footnotes. Here he embraced Marx as a prophet—guided not so much by Old Testament wrath as by the idea (written by Marx and his pal Friedrich Engels at a peak revolutionary moment) that what might just be heaving into sight would be “an association in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.” This Marx, to him, was “one of the first and greatest of modernists.” By modernism he meant “any attempt by modern men and women to become subjects as well as objects of modernization, to get a grip on the modern world and make themselves at home in it.” But in All That Is Solid, despite the title beautifully lifted from The Communist Manifesto, Marshall was not so much heralding a visionary future as celebrating, and worrying about, the possibilities of the present. “To be modern,” he wrote, “is to experience personal and social life as a maelstrom … To be a modernist is to make oneself somehow at home in the maelstrom, to make its rhythms one’s own, to move within its currents in search of the forms of reality of beauty, of freedom, of justice, that its fervid and perilous flow allows.”

The saga of All That is Solid concerned a lot more than theory—it concerned taking seriously the whole onrush of modern life. It was, in a way, a self-help book to end all self-help books—a book that said that you’re not alone in knowing you need help to place yourself in a swarming, self-undermining, change-crazy world. He began with Goethe’s Faust, emphasizing the usually neglected Part II, where the eponymous hero-villain transmogrifies into a ruthless real-estate developer, a personification of “the tragedy of development” and an anticipation of Stalin, Le Corbusier, and the hometown urban wrecker Robert Moses, whose gash of a Cross Bronx Expressway sliced through the Berman family’s original neighborhood in the South Bronx. It was in his ability to move through levels that the book was a life-changer, for me and many others. He imagined an eight-mile-long mural that might, in some glowing future, be painted onto the walls of the Cross Bronx, He always knew that, even in a poisoned world there was still, and always, a same old story to be told, of “a fight for love and glory,” when In the closing chapters of All That Is Solid, he swept triumphantly into the present with tributes to Jane Jacobs, Spalding Gray, and graffiti artists without number or, often enough, public names. Later he welcomed Cyndi Lauper, Queen Latifah, and the Beastie Boys into his personal pantheon. He called Times Square a place where “Cubism is realism.” He proclaimed “the right to the city” and “the right to be part of the city spectacle.” He was a one-man jazz band.

Get your eyes down from the skyscrapers (whether of steel or of “theory”), he was always saying, and look down at the street, which is not only a place where the traffic passes but a place where the city, that great human invention, lives. For years, we would get together to talk about life, love, the Sixties, the endless post-Sixties, Dissent, and what was wrong with postmodernism, but often enough the first thing he wanted to talk about was a down-on-his-luck (or down-on-capitalism) cabbie he’d just met who needed some money quick for some worthy purpose—refusing, like his father, to believe that he might be getting hustled, like his father.

His first book was called The Politics of Authenticity: Radical Individualism and the Emergence of Modern Society, in which the streets and thoughts of 18th-century French-speaking Europe were the incubators of “festivals of democracy” as imagined or anticipated by Montesquieu and Rousseau. “Whoever you are or want to be,” he wrote at the end of that book, paraphrasing Trotsky, “you may not be interested in politics, but politics is interested in you.” Sometimes his “authenticity” could be blunt, sentimental, and even, on rare occasions, unforgiving. He could be kinder to grandparents or great-grandparents than to parental types. In 1975, in a harsh, awkwardly “balanced” front-page New York Times Book Review, he accused Erik Erikson of acting in bad faith, hiding in a closet, by effacing his Jewish identity. He could be tough on other people’s sentimentality, and equally on snobbery: When Susan Sontag once told him she would have had a better life if she had been born into medieval Europe, where an intellectual could get proper respect, he reminded her that things were not then so great for women.

“Marxist humanism” was sometimes his label of choice, but he was not much into labels, feeling no qualms about recruiting his Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud into some discordance if not concordance. He wanted “a synthesis of the culture of the Fifties with that of the Sixties: a feeling for complexity, irony, and paradox, combined with a desire for breakthrough and ecstasy; a fusion of ‘Seven Types of Ambiguity’ and ‘We Want the World and We Want it Now.’” That was a lot to ask and no one could sustain these tensions beyond their breaking points.

He mellowed, ripened, and kept going to demonstrations. He was primed to know that modernity was no picnic, and so, with immense stamina, he was able to outlive personal tragedy (he lost his first son at age 5) and a Jobian sequence of ailments, to father and help raise two boys to manhood. In later work, as when he came to write On the Town, about Times Square, he mostly refused to let distaste for 21st-century Disneyfication drown him in nostalgia, though he could bend over backwards toward populist enthusiasm for any sign of insurgent life anywhere, however obscure. He liked to say that the great New York experience—in fact, the great achievement of New York art—was the street, which always remained busy with self-creation. He “hurled little streets upon the great,” as Yeats wrote of his beloved revolutionary Maud Gonne. When, in 1987, he lectured on All That Is Solid in Brazil, he made front pages when he attacked the country’s supermodernist architect and disciple of the street-hating Le Corbusier, Oscar Niemeyer. But in a 1988 preface, he could even find understanding words for Niemeyer.

He died of an out-of-the-blue heart attack in one of his favorite schmoozing sites, the West Side’s Metro. Metro. He was a true metropolitan. All that was solid in his heart and mind refuses to melt into air.

Todd Gitlin (1943-2022), was a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph.D. program in Communications at Columbia University, and the author of among other books The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street; and, with Liel Leibovitz, The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election.