Mel Bochner Returns to The Jewish Museum

The conceptual artist’s bold typographic works are on display in New York City

Though it’s been more than 50 years since he’s shown his work there, artist Mel Bochner’s history with The Jewish Museum has been pivotal to his career. After all, his first job after arriving in New York in 1964 was as a security guard at the institution; while guarding a show by painter Phillip Guston, a chance meeting with a faculty member led to a teaching position at the School of Visual Arts, where he presented his first career show, which became a crucial moment in the conceptual art movement. And there is, of course, the infamous story of his getting fired from his security gig after falling asleep behind a Louise Nevelson sculpture, exhausted from nights spent painting.

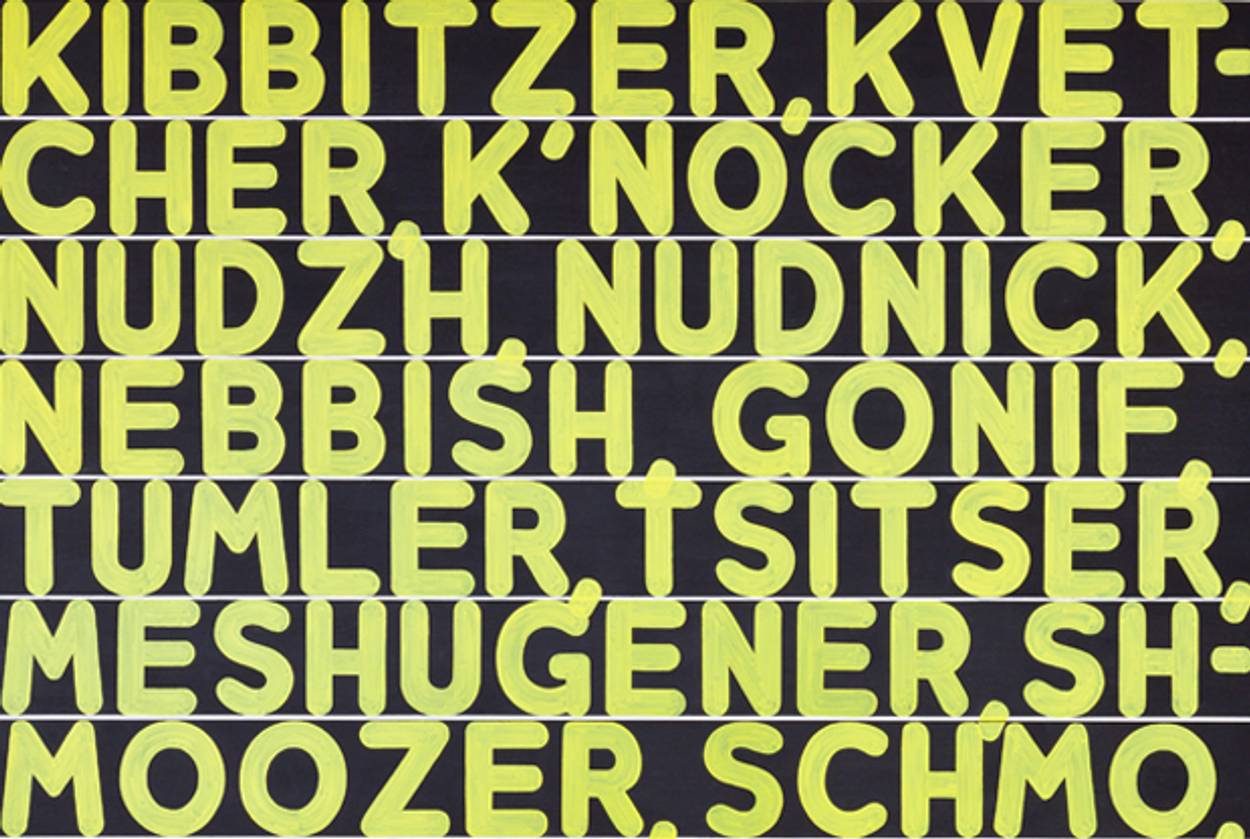

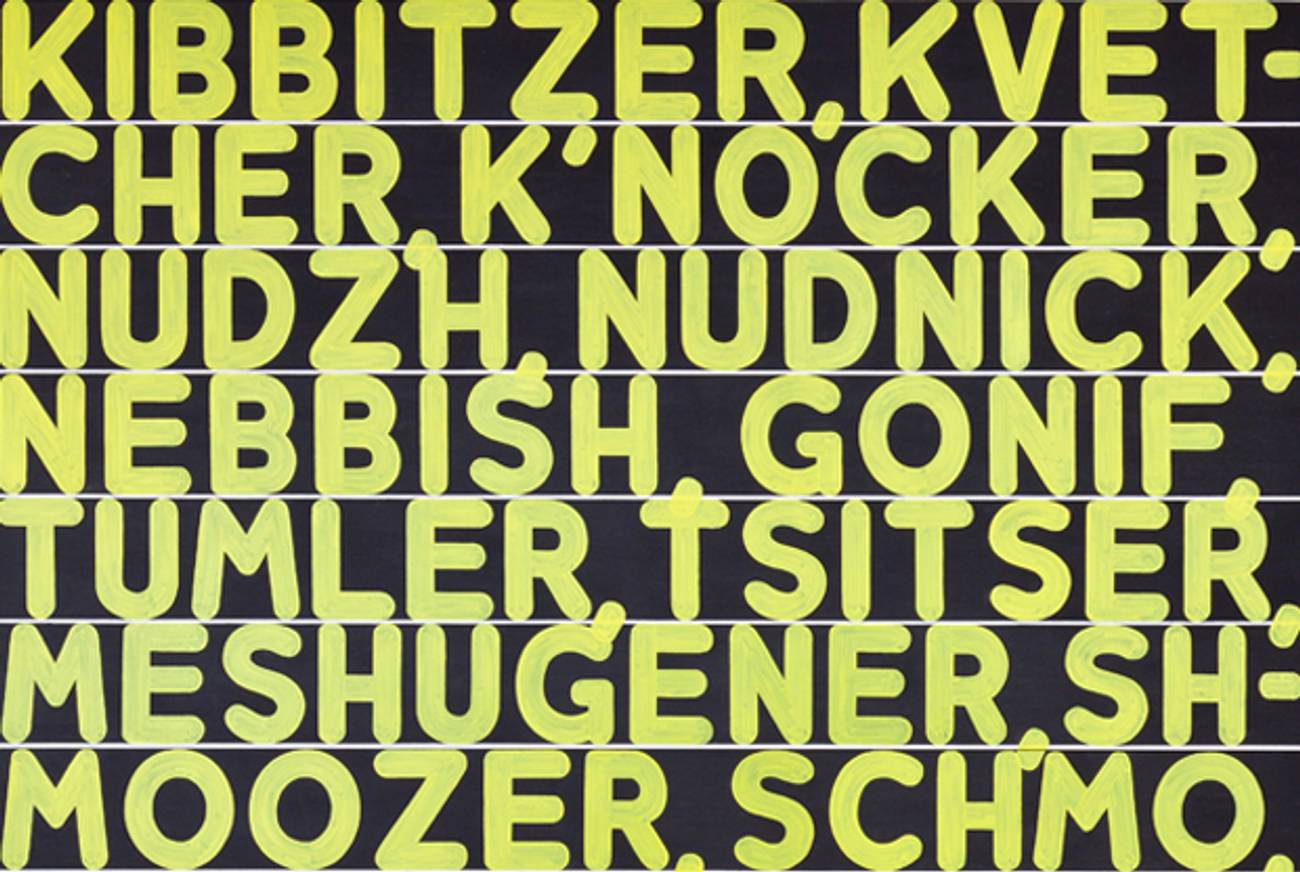

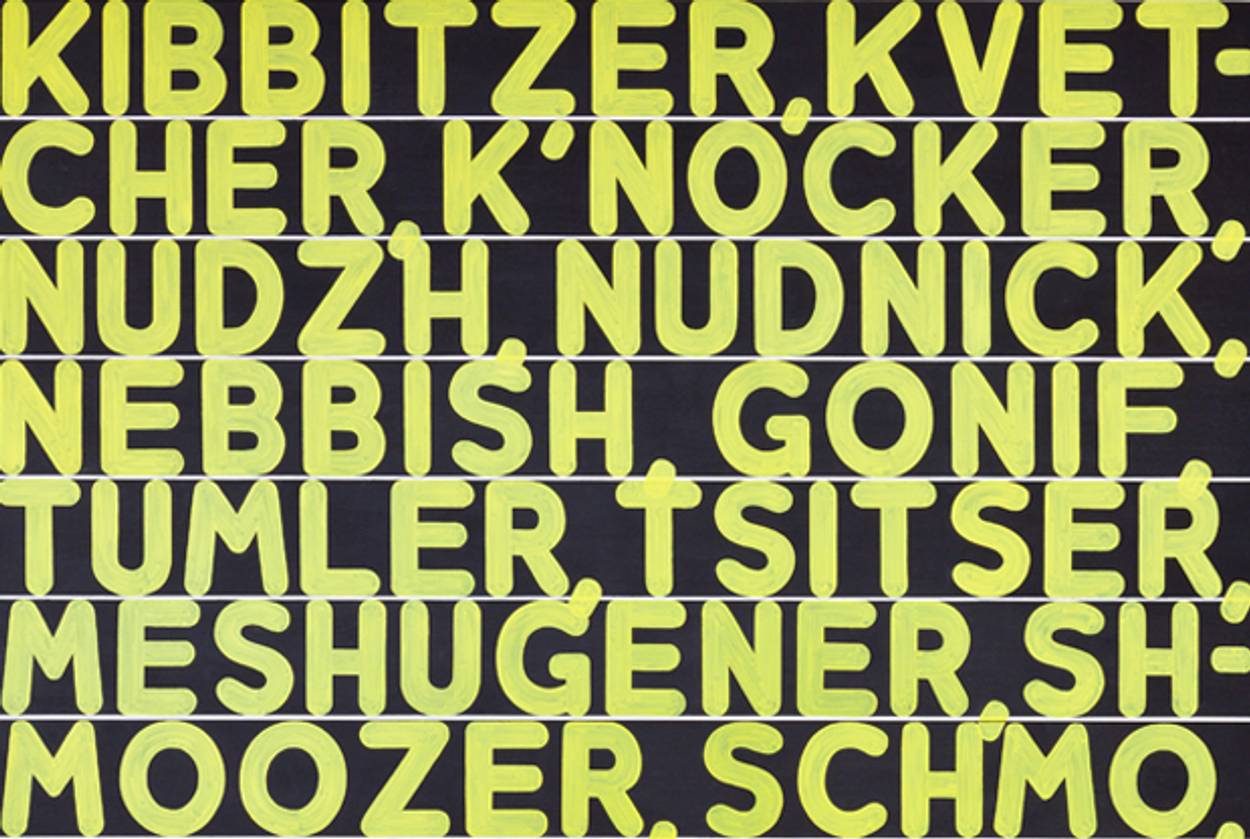

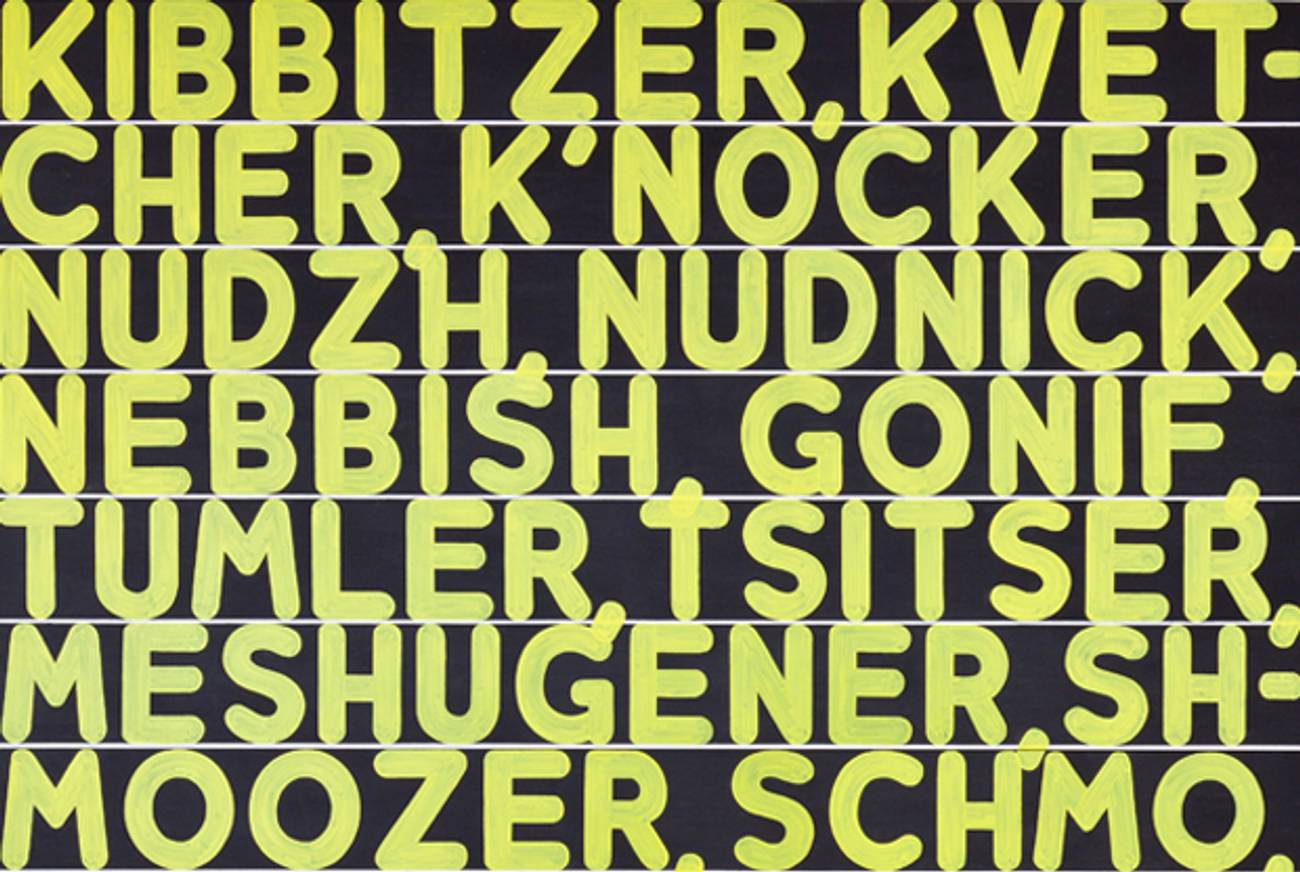

But in “Mel Bochner: Strong Language,” opening today at The Jewish Museum, Bochner’s career-long exploration of language, meaning, and the space in between makes a bold impression of its own. A survey of his typographic paintings, alongside several drawings and published articles, displays the artist in one of his most comprehensive shows to date. I spoke with Bochner about the collection.

In preparing for this interview, I was impressed by the strong notion of control in your work—your deep interest in philosophy and the principles of language. But hearing you speak with Norman Kleeblatt, the exhibition’s curator, I was struck by your interest in the entropy of language, and the parts that are out of your control. Do you ever notice a tension between the two concepts?

Oh absolutely. It’s the thing that drives one forward–exploring that boundary where meaning disintegrates. And what happens in that disintegration, that’s a lot of what the “Blah Blah Blah” paintings are about. We use language all the time and we think we know what we’re saying, but the truth is, we don’t always know what we’re saying. And I think my paintings are about exploring the slipperiness of language.

This is the first time you’ve shown at The Jewish Museum since 1970. What significance does having an exhibition of your work at this museum hold for you?

Well, showing any work at any museum is significant. The fact is that the museum as it is right now, it has no relationship to the museum I worked in, because they tore the whole building down and rebuilt it [laughs]. I don’t even know where the bathrooms are anymore. So there’s no nostalgia involved.

I know it seems to some people like the closing of some improbable circle, but it’s probably just like a big zig-zag.

But I think now, with a new director and a new direction, they are re-establishing their relationship with contemporary art, and maybe mine is one of the first exhibitions to announce that.

What inspired you to adopt “leet speak” as a language used in your paintings?

My daughter explained it to me, and it seemed like a kind of interesting world, to take it out of the electronic media and put it as a painting. The question is how to make that painting—it’s not the leet speak that particularly interests me in that painting [laughs] or the fact that it says “shit.” It’s that image, painted in that way, which takes it, which almost appropriates it out of electronic media, and makes it a painting. And that’s the space that that work explores—how to make that a painting. There’s a million ways you could paint that, and that’s a very specific way of painting.

And what meanings it suggests are based on that choice?

Exactly. The way in which the works are made are as important to me as what they say. And I try to work the relationship between those two things to expand the meaning of the text, to incorporate the meaning of the process.

In the paintings done on velvet, the results of the painting process aren’t as predictable as they are in your work on canvas. There’s a prevailing notion of “challenge” in your work—challenging the observer, and even yourself as an artist. Are the works on velvet an extension of that?

That’s exactly correct. The work on velvet is about surrendering control.

Those paintings on velvet, when I first started making them, I would look at them and just shake my head, wondering ‘What the hell is this?’ Because they’re kind of a shock. But now I’ve gotten used to them [laughs].

And that’s your most recent challenge?

It all goes on together. It depends. I don’t know what my next painting is going to be. And I don’t know what it’s going to look like. But that’s where I want to be in the world.

Jared T. Miller is a freelance journalist based in New York. He has written for Time, the New York Daily News, ABC News and The Forward, among other publications.

Jared T. Miller is a freelance journalist based in New York. He has written for Time, the New York Daily News, ABC News and The Forward, among other publications.