Mourning Is Complicated

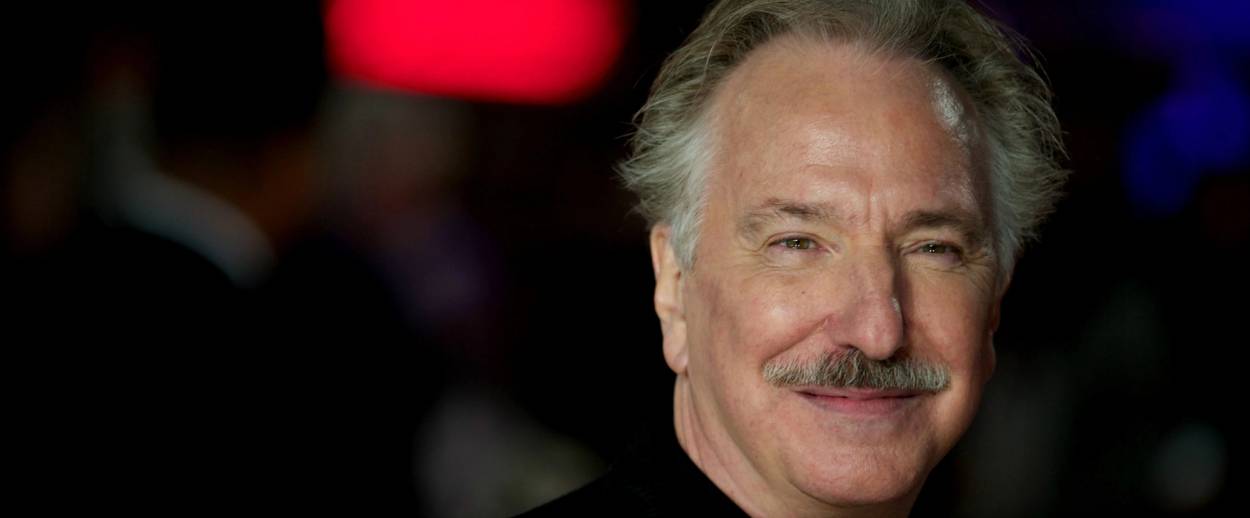

When Alan Rickman died, social media blew up with mini lamentations for the widely beloved actor. But the moment produced great ambivalence within me.

Too many of my days seem to begin with the discovery of dismal tidings, almost always encountered via Twitter. Thursday morning’s grim news concerned the death of actor and director Alan Rickman, who had passed away, at age 69, from cancer. My social media channels were soon awash in expressions of grief.

Online, it seemed that almost everyone I knew (or “followed”) was devastated by this loss. Like me, most had not known Rickman personally. It was hard not to think of similar “viral” outpourings; indeed, just this week, the death of David Bowie prompted a Vox article that addressed “why we grieve artists we’ve never met, in one tweet.”

As I thought of Rickman’s family, friends, and colleagues—and the illness that had taken his life—I was saddened, too. I remembered the day when my high school French class, having read Les Liaisons Dangereuses, ventured to Broadway to see the stage adaptation, and I encountered Rickman’s extraordinary acting gifts for the first time. Although I’ve (somehow) never entered the Hogwarts universe, I could have joined in the collective mourning with a tweet or Facebook wall post similar to dozens that I saw. But something made me resist any attempt to condense my reaction to a virtual sound bite.

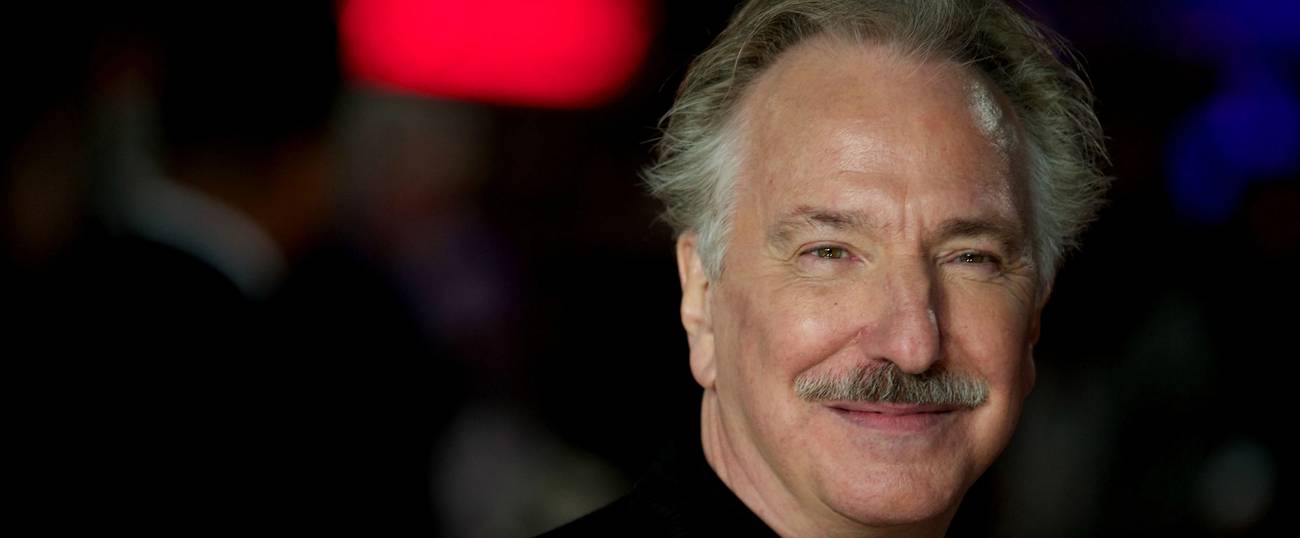

In truth, I was troubled by news about Rickman years before: He co-edited, directed, and strenuously promoted a play, My Name is Rachel Corrie, which is based on writings by the young American activist who died in Gaza in 2003 when, as The Guardian phrased it, “she put herself between an Israeli army bulldozer and a Palestinian home it was about to demolish.” Edward Rothstein’s analysis of the play in the New York Times is perhaps the most nuanced and even-handed discussion of the work that I’ve seen; Adam Chandler’s post on Tablet provides additional, essential context about the circumstances surrounding Corrie’s death and the subsequent aura of martyrdom that surrounded her—an image that My Name is Rachel Corrie advanced and perpetuated.

Rothstein wrote:

What could be less controversial than this heroine, with her Utopian yearning to end human suffering and her empathy for Palestinians living in a hellish war zone, their homes and lives at stake? Her death becomes a tragic consequence of her compassion and, apparently, in performance, has the power to spur tears.

But there is something disingenuous here. In an apparent effort to camouflage Corrie’s radicalism and broaden the play’s appeal, its creators elided phrases that suggested her more contentious view of things — cutting, for example, her reference to the “chronic, insidious genocide” she says she is witnessing, or her justification of the “somewhat violent means” used by Palestinians.

As a dramatization of a young woman’s political education, the play also never has to hold itself accountable for what seems naïve. “I’m really new to talking about Israel-Palestine,” Corrie says soon after arriving in Israel, “so I don’t always know the political implications of my words.”

Whether cultivating the myth of Rachel Corrie as a tiny, saintly David murdered by the brutal Israeli Goliath was Rickman’s intent, I cannot know. I do know that in 2006, after the Israeli disengagement from Gaza—and Hamas’s electoral victory there—he declared that “her voice is like a clarion in the fog and should be heard.” The snippets cited by Rothstein above, however, cast some doubt on that claim. And I do know that you needn’t delve too deeply into Google to find anti-Israel activists celebrating the work in ugly ways.

Of course, as a Jew, I can find plenty of historical examples of artists I admire greatly whose anti-Semitic writings or utterances I might find similarly discomfiting. But there is something different about those whose lifetimes have overlapped with mine. That makes my discomfort more acute. To be sure, Rickman isn’t the only artist—or even the most problematic one—to have evoked this web of feelings; he’s merely the most recent.

Part of me wishes that I’d sensed no ambivalence on Thursday; that I’d simply scribbled out and posted a quick #RIP. But I also know from offline experience that grief can be complicated—tinged with anger, regret, all kinds of things that we don’t easily admit or talk about. Perhaps social media will one day accommodate those complexities and contradictions, and everyone behind the avatars will understand (or at least respect) them. I don’t think we’re quite there yet.

Erika Dreifus is a writer and editor in New York and the author of Quiet Americans: Stories. Visit her website and follow her on Twitter, where she tweets on “matters bookish and/or Jewish.”