My Own Private Tisha B’Av: The Chinese Restaurant

There’ll never be a Moo Goo Gai Pan quite like Schmulka Bernstein’s

To mark Tisha B’Av, The Scroll asked a few writers to reflect on a private Jewish temple they’d lost, a place that was meaningful to them and no longer exists.

Despite the plethora of kosher dining options near my home in New York City, there will always be a gaping hole in my heart, and stomach, from the demise, a quarter of a century ago, of Bernstein-on-Essex, aka Schmulka Bernstein’s, which, I, and my family and friends patronized almost weekly, for close to 30 years.

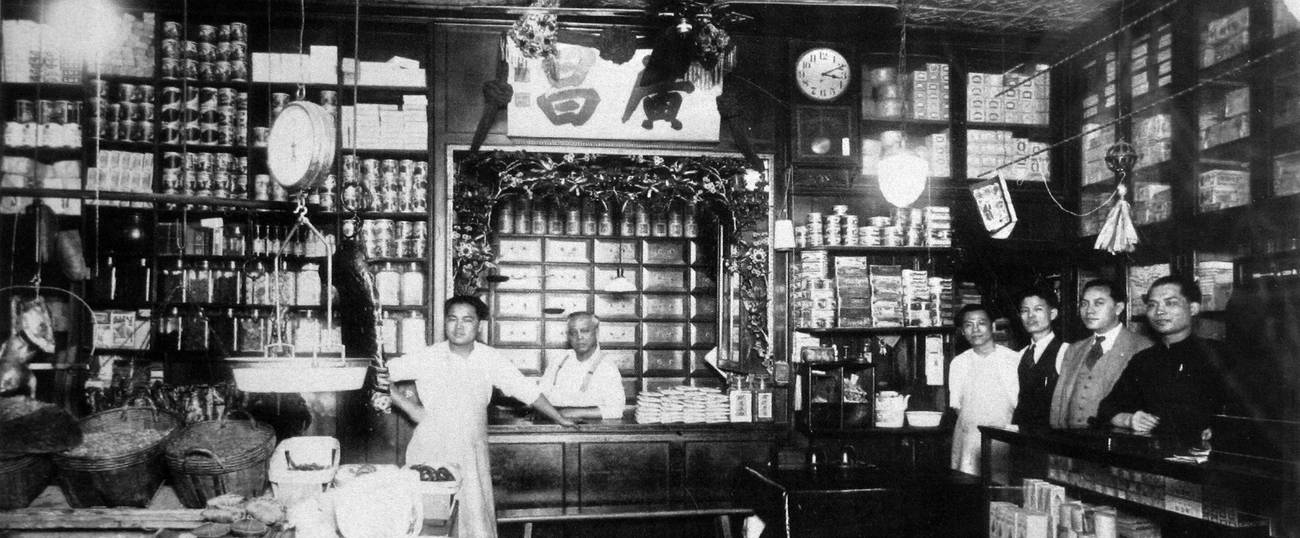

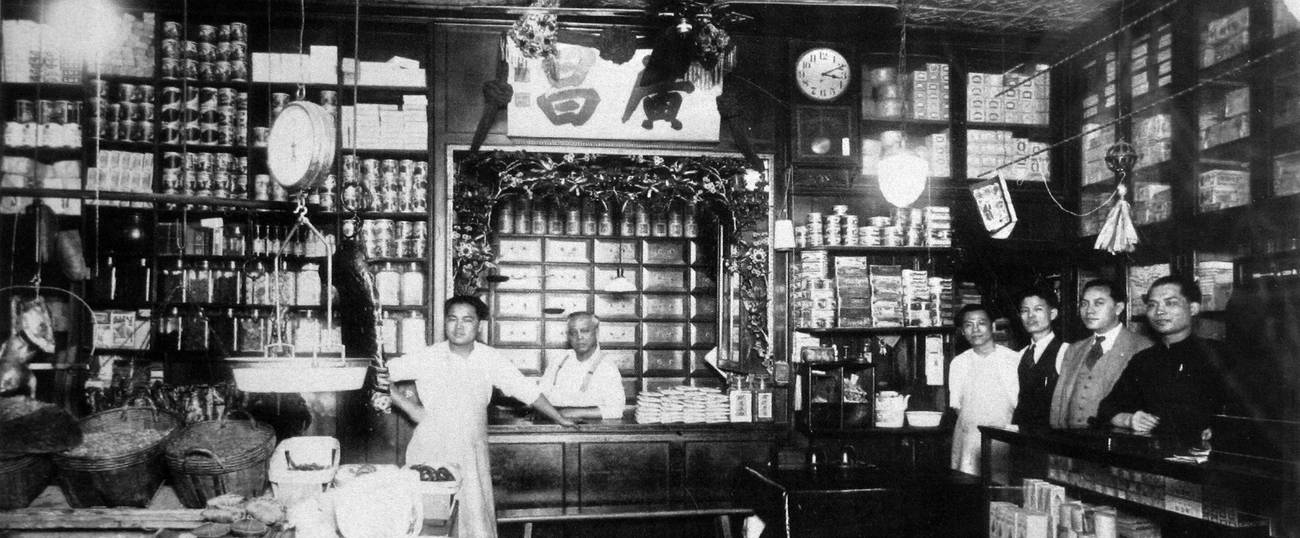

Schmulka Bernstein’s was located in the heart of the Lower East Side, at 135 Essex Street, a few storefronts away from a Judaica shop whose window featured a bar mitzvah-boy-mannequin, clad in a suit and draped in a satin tallit, that never failed to capture the attention of my young children. Bernstein’s slogan was “where kashruth is king and quality reigns,” however, despite featuring the finest deli I have ever experienced, it is best known for the fact that, in 1960, it added a second menu, placed red-tasseled Chinese caps on its waiters, and became the New York’s first kosher Chinese restaurant, adding to its marketing the promise “Where West Meets East For a Chinese Feast and Kashruth is Guaranteed.”

For probably 15 years, Bernstein’s was the only restaurant in New York that featured kosher versions of Moo Goo Gai Pan, “Sweet & Pungent Spare Ribs,” Egg Foo Yung, and something called Chow Mein Bernstein, which was, according to an early menu, “a version of a favorite gourmet style—made with fresh chicken livers, chicken, sliced beefsteak with fine Chinese vegetables,” all for three dollars and fifty cents!

But Schmulka Bernstein’s was far more than its food. While attending college in the mid-60’s, it was a home away from home for me and generations of students who packed the place on Thursday and Saturday evenings, when it was open until 3 A.M. There is an apocryphal, yet believable, story that a group of Yeshiva College students spending the year in Israel pooled their funds and dispatched one of their number to New York with explicit instructions to fill two suitcases with “Schmulk’s” food and then, without seeing or contacting a single family member, return to Israel on the next flight. It was our kosher clubhouse: in those years, I don’t think I ever entered that fragrant paradise without encountering someone I knew.

The next decade saw me married with children, and a visit to Bernstein’s became a fixture of our Sunday entertainment. Who needed Disneyland, when we could drive to the Lower East Side, wait on line for an hour for a table, eating franks, and basking in those exotic surroundings and smells. We then finished the afternoon with a ride through the “automatic car wash,” at the corner of Houston and Lafayette, with soppy cloth and rubber tentacles, loudly speckling and slapping the windshield with soap and water, followed by a wind machine on a wheel, traversing the length of the car, blowing away the rinse and thrilling our young children.

However, as fewer and fewer Jews worked and lived on the Lower East Side, and competition arose (the best known was the aspirational Moshe Peking, which opened on West 37th Street in 1977), less people were willing to make the trek to Essex Street, and by the early 1990’s, after the death of its iconic and laconic owner, Sol Bernstein, the business was sold, and within a few years, closed, breaking the hearts of thousands, and relegating to memory, a veritable temple dedicated to tradition, camaraderie, and, weirdly and gloriously, Chinese and Jewish food.

Morton Landowne is the executive director of Nextbook Inc.