Neoliberal Twee

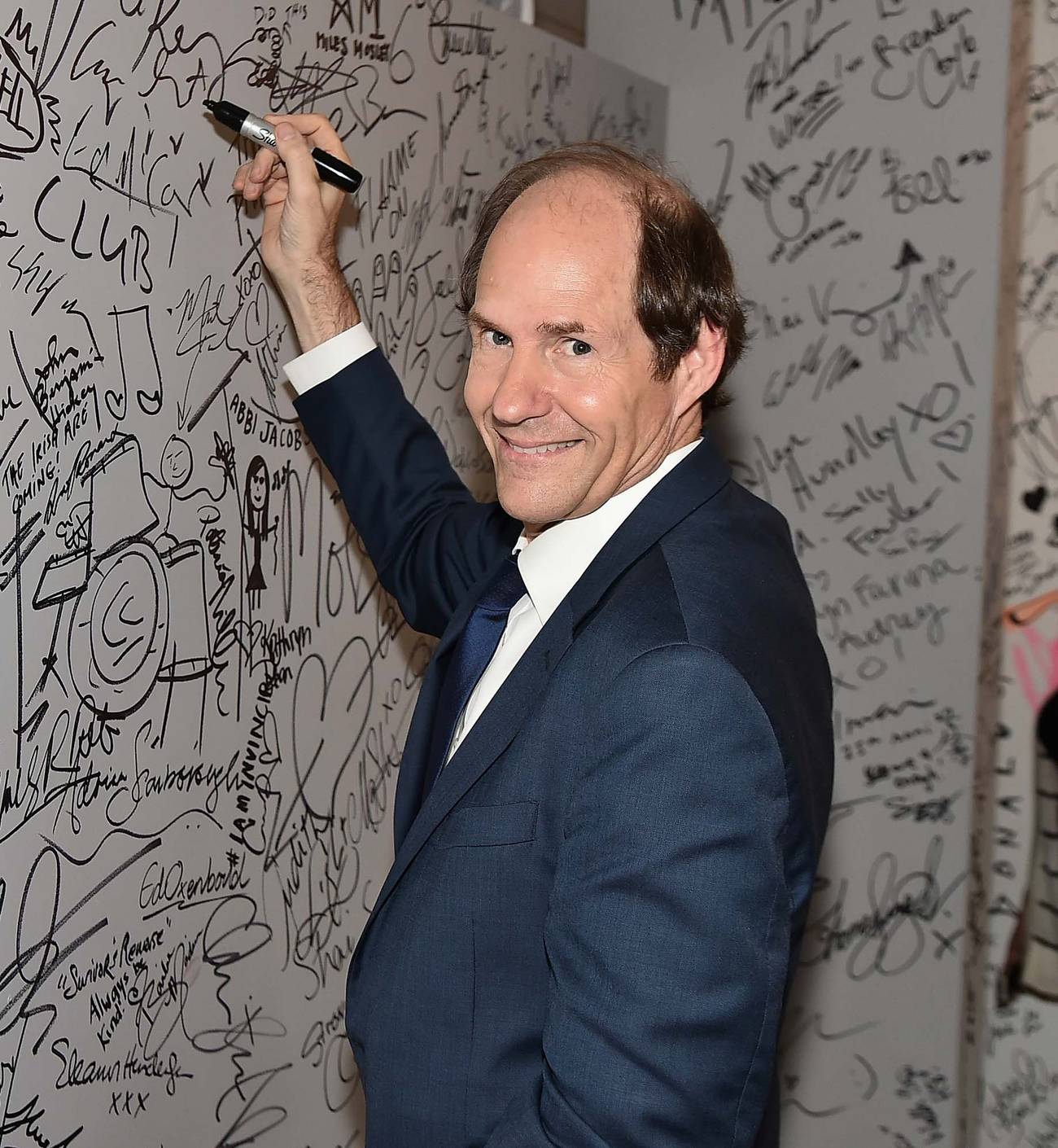

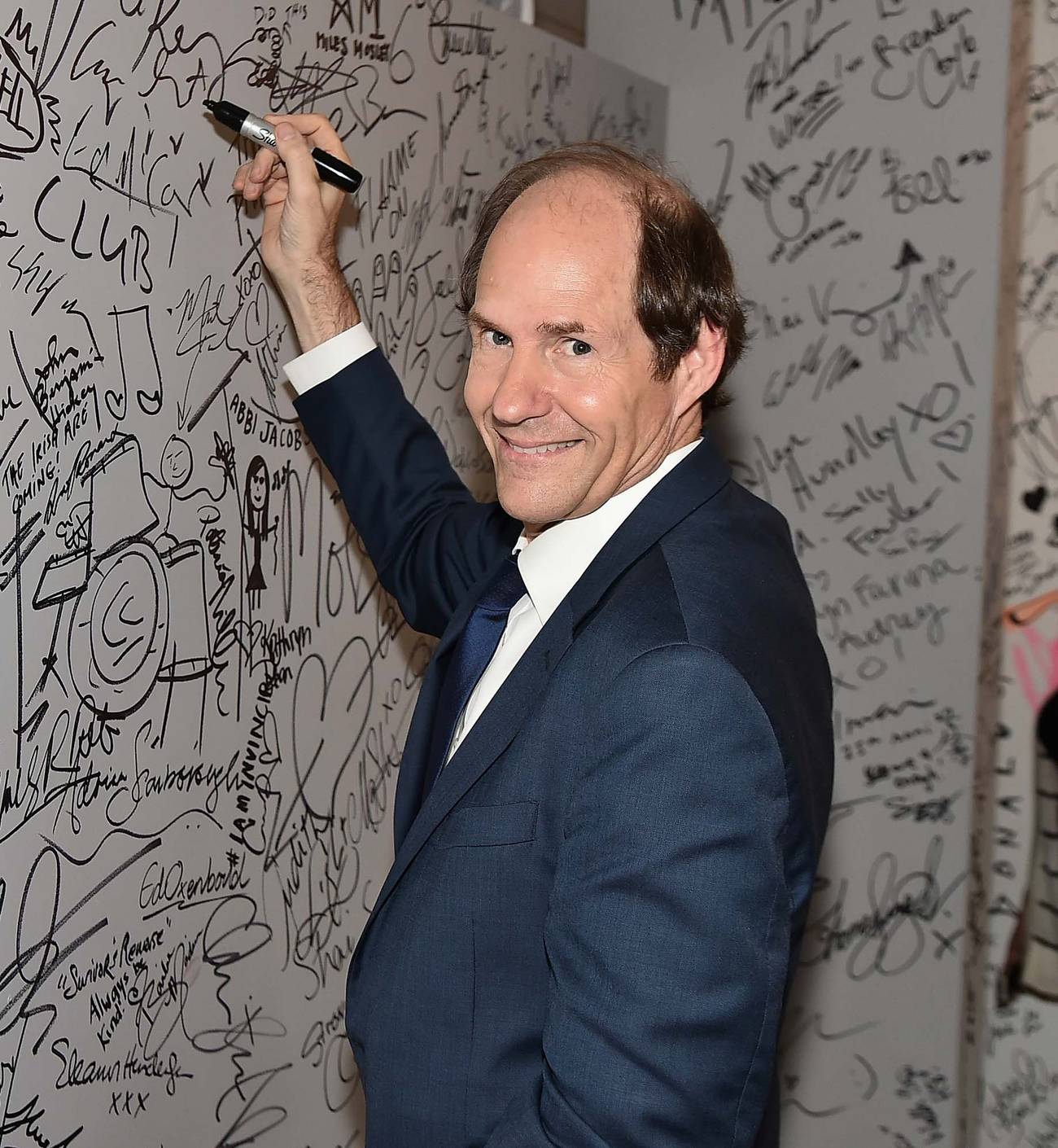

Cass Sunstein’s latest TED Talk of a book offers the kind of technocratic whimsy that left and right can agree to hate

If you open a copy of the Encyclopedia of Political Ideology and look up “technocratic neoliberalism,” the dominant policy paradigm since the end of the Cold War in the contemporary West, you will find a picture of Cass Sunstein—or at least you would, if such an encyclopedia existed. Following a successful career as a legal scholar at Chicago, Columbia, and Harvard, and as a public intellectual who in his early years wrote thought-provoking books on subjects including the cost of government and Franklin Roosevelt’s Second Bill of Rights, Sunstein broke out of the highbrow ghetto in 2008 to reach a much larger audience with a book he coauthored with University of Chicago economist Richard Thaler, Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

Nudge was not Sunstein’s first venture into the genre of midwit nonfiction. That was Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge in 2006. Perhaps it is coincidence, but Infotopia came out only a year after the publication of Freakonomics: A Rogue Economist Explores the Hidden Side of Everything, co-authored by Steven Levitt and the journalist Stephen J. Dubner. Freakonomics became a global bestseller, spawning a blog, a podcast, and sequels including SuperFreakonomics: Global Cooling, Patriotic Prostitutes, and Why Suicide Bombers Should Buy Life Insurance (2009), Think Like a Freak: The Authors of Freakonomics Offer to Retrain Your Brain (2014), and When to Rob a Bank: ...And 131 More Warped Suggestions and Well-Intended Rants (2015).

Levitt teaches economics at the University of Chicago, where Sunstein taught law for 27 years before joining the faculty of Harvard Law School. I do not know whether the sudden superstardom of Levitt, his younger Chicago colleague, inspired Sunstein to try his hand at the middlebrow genre of pop nonfiction. There were certainly other exemplars of buckraking in this vein to be followed, including Malcolm Gladwell, whose pop psychology bestsellers included Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking (2005) and The Tipping Point: How Little Things Can Make a Big Difference (2006), and Spencer Johnson, author or co-author of Who Moved My Cheese? An Amazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and Your Life (1998) and The One-Minute Manager (1982).

Books of this ilk are written according to a formula as rigid as that of a cozy mystery or a Tolkien-clone fantasy trilogy. The author, sometimes an academic, poses as a defector who shares new research insights with general readers, who are thrilled to be let in on the scholarly establishment’s supposed secrets. Thus Steven Levitt, a conventional economics professor, becomes “a rogue economist,” and Simon and Schuster’s promotional material describes Cass Sunstein’s 2014 book, Conspiracy Theories and Other Dangerous Ideas, as “The most controversial essays from the bestselling author once called the most dangerous man in America—collected for the first time.”

The format of pop nonfiction is rigidly defined. Books are usually brief, little more than pamphlets, with small pages and big print. They have catchy one- or-two word titles, which are sometimes slangy or trendy neologisms: Freakonomics, Infotopia, Blink. The author juggles anecdotes and dogmatic assertions and invokes this study and that, while dazzling readers with confident erudition and leaping rapidly from topic to topic before readers have time to question what they are told.

Most of these books purport to use one or another recent academic theory as a Rosetta stone that reveals and explains otherwise hidden patterns in the world. This would be difficult to do in the case of Triassic-era botany or quantum physics, so most of the pop nonfiction bestsellers deal with everyday life, office work, or politics, allowing readers to think of examples from their own lives. As in other kinds of genre nonfiction and genre fiction, readers who liked the first book often shell out money for sequel after sequel, so they can experience the same pleasure in the same predictable way, over and over again.

On hitting pay dirt in 2008 with his co-authored second contribution to this genre, Nudge, Sunstein became one of the world’s leading thinkers in the eyes of the overclass midwits who read The New York Times and The Economist, listen to NPR, and watch TED Talks and PBS. Alone or with co-authors, Sunstein has cashed in on his celebrity by cranking out derivative books at high speed. Excluding a few conventional scholarly works, Sunstein’s bibliography over the last decade-and-a-half includes Infotopia (2006), Nudge (2008), On Rumors: How Falsehoods Spread, Why We Believe Them, What Can Be Done (2009), Going to Extremes: How Like Minds Unite and Divide (2009), Simpler: The Future of Government (2013), Why Nudge? The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism (2014), Valuing Life: Humanizing the Regulatory State (2014), Wiser: Getting Beyond Groupthink to Make Groups Smarter (2014), Choosing Not to Choose: Understanding the Value of Choice (2015), The Ethics of Influence: Government in the Age of Behavioral Science (2016), #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media (2018), The Cost-Benefit Revolution (2018), Can It Happen Here? Authoritarianism in America (2018), Conformity: The Power of Social Influences (2019), On Freedom (2019), Trusting Nudges: Toward a Bill of Rights for Nudging (2019), How Change Happens (2019), Too Much Information: Understanding What You Don’t Want to Know (2020), Averting Catastrophe: Decision Theory for COVID-19, Climate Change, and Potential Disasters of All Kinds (2021), Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgment (2021), and Sludge: What Stops Us from Getting Things Done and What to Do About It (2021), co-authored with Richard Thaler. Note that as Sunstein’s books get ever slighter, they are published more frequently—four books in 2019, and three in 2021. He is the James Patterson or Barbara Cartland of public policy.

Now at Harvard Law School, Sunstein is the founder and director of the Program on Behavioral Economics. In its application to public policy, behavioral economics attempts to build upon and modify the earlier “law and economics” school, centered among libertarian economists and lawyers at the University of Chicago, where Sunstein taught in his youth. The behavioralists retained the neoclassical assumption that each person has an objective self-interest, which can be defined by others as well as by that person. But they rejected the idea that people necessarily know what their own self-interest is. Factors like short-termism may lead people to undertake actions that they later regret.

Wise people everywhere have known this for hundreds and thousands of years. But in most societies, customs, religious commandments, statutes, and ordinances have sought to align individual behavior with good behavior. As an alternative, Sunstein and Thaler proposed in Nudge that governments adopt a philosophy of “libertarian paternalism.” It is paternalistic in that governments would attempt to protect citizens from their own self-destructive impulses, and libertarian inasmuch as it would do so indirectly, by creating “choice architectures” relying on incentives and psychological tricks, rather than directly, by prohibitions or mandates. For example, in public school cafeterias, healthy foods would be placed up front, and unhealthy snacks and desserts, rather than being banned outright, would be available but semi-hidden, to trick youngsters into going for fruit rather than cupcakes (this suggests an imperfect understanding of child psychology).

At the time of its publication, the assessment of Nudge by intellectuals was mostly negative. Libertarians pointed out, correctly, that libertarian paternalism is a contradiction in terms; Sunstein and Thaler were simply advocating government paternalism. For their part, progressive and conservative intellectuals alike tended to reject libertarian paternalism as secretive, manipulative, technocratic despotism. It sought to replace publicly understood laws preceded by public debate with the decisions of an all-wise, benevolent caste of mostly unelected “choice architects” in government offices, who allegedly understand the interests of ordinary people better than ordinary people themselves, and who would use a variety of subtle psychological tricks to manipulate the masses into doing what they ought to do for their own good. As the Johns Hopkins political scientist Steven M. Teles wrote in The American Interest in a review of Sunstein’s first Nudge sequel, Why Nudge?, “the language about helping people using their higher values over their lower ones seems to be a bit of a smokescreen for an argument designed to legitimate enforcing on an individual what the regulator takes to be superior judgment.”

But if the intelligentsia was not impressed by Nudge and its sequels, the political class, as addicted to fads as corporate management—remember Reinventing Government?—jumped on the bandwagon. President Barack Obama appointed Sunstein to be his regulatory czar in the Office of Management and Budget’s Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA), and there was much buzz about nudging in London, Paris, and other capitals. President Joe Biden recently appointed Sunstein to help roll back restrictive immigration rules in the Department of Homeland Security—an easy job, one imagines, because under Biden the federal government has almost completely ceased to enforce federal immigration law.

Sludge, the latest book by Sunstein, complements Nudge in addition to rhyming with it. Sunstein’s concern in this book is not nudging people toward desired outcomes, but removing barriers—chiefly excessive paperwork—that turn people away from desired outcomes, like voter registration or welfare state programs for which they are eligible. Having spent much of the last two months trying to correct an error with my electric utility account, and having recently wasted time filling out multiple pages of forms in advance of my annual physical, I am sympathetic to any Alexander who wants to cut the Gordian knot of red tape. But there are two problems with Sunstein’s account of sludge.

The first is his partisanship. There is a tension between his neutral, technocratic tone, and his partisan preferences, which is manifest in his selection of examples of sludge itself. Outside of the green wing of the Democratic Party, there is a widespread consensus that the worst form of government-created sludge today consists of excessive environmental regulations, including project-delaying requirements for environmental impact statements, which act as a tax on the poor by making many things, from housing to infrastructure to food production, either more expensive or legally impossible—without much environmental benefit to show for it.

On reading Sludge, I expected Sunstein to discuss the ways that excessive and misguided environmental regulations paralyze public and private construction and drive homeowners and landowners crazy. Not a word: only two mentions of the Environmental Protection Agency on two pages, in lists of federal agencies.

While excluding any discussion of onerous environmental regulations that might upset the green lobby on the left, Sunstein devotes much of Sludge to discussing ways that poor people who are eligible for various means-tested welfare state benefits never access them because the potential beneficiaries just give up rather than fill out paperwork or contact various offices. In taking it for granted that a large population of American workers can only survive with means-tested government assistance, Sunstein is not a traditional liberal, but a neoliberal.

If schools had coin-operated toilets, Sunstein’s priority would be reducing the paperwork needed for the government to provide coins to poor kids.

In the New Deal regime that lasted between the 1930s and the 1970s, created by Roosevelt and ratified by Dwight Eisenhower and Richard Nixon, workers who worked full time were generally not poor and could live on their wages, thanks to a high degree of unionization, which also benefited nonunionized workers, and minimal immigration of unskilled workers during the mid-20th century. Today, however, according to a University of California, Berkeley study in 2013, a quarter of American workers rely on at least one welfare program, as do more than 50% of fast-food workers.

Under today’s neoliberal system, the government allows employers to pay wages that are too low to survive on, and then the government uses taxpayer money to bail out the underpaid workers, with programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC)—a subsidy to poverty-wage workers—and in-kind benefits like food stamps and housing vouchers. The Labor Center at Berkeley has calculated that welfare for low-wage American workers costs taxpayers $150 billion each year. As Teresa Ghilarducci and Aida Farmand noted in The American Prospect in 2019, “The heavy reliance on the EITC, rather than the minimum wage and the strength of trade unions, is one major reason why the U.S. leads the OECD in the share of jobs that pay poverty wages—a full 25.3 percent of jobs are poverty jobs, compared to 3 percent of jobs in Norway.”

In the neoliberal elite subculture in which Sunstein has flourished as an author, expert, and policymaker, providing a living wage to all Americans is off the table—we’re not going there, it’s crazy Bernie Sanders talk. Sunstein, a typical neoliberal in this sense, praises the EITC for its relative lack of paperwork:

For the EITC, the secret of relative success is an unlikely coalition between business interests and those seeking to help the working poor. Business interests much like the EITC because it creates an incentive for low-wage work. Those who care about the working poor like the EITC because it makes the working poor less poor. The two interests have been able to work together—not to make the program as generous as it might be, but at least to reduce sludge.

In his discussion of school lunches, Sunstein is just as careful not to stray from the neoliberal herd into social democratic or populist territory. His sole concern is to make it easier for poor kids and their families to sign up for subsidized school lunches. He does not ask an obvious question: How can state governments and local school systems run a public-school monopoly at taxpayer expense, requiring all but a few private-school and home-schoolers to attend, and yet demand at the same time that the children pay for their own meals at school? Should government hall monitors collect tolls from students walking to class? Should K-12 schools have coin-operated bathrooms?

Sunstein just wants to reduce the paperwork, for good programs and awful programs alike. If schools did install coin-operated toilets, Sunstein’s priority would be reducing the paperwork needed for the government to provide coins to poor kids.

I have saved the best for last. As his cure for reducing sludge created and managed by federal bureaucracies, Sunstein proposes that all agencies undertake sludge audits. That’s right. The cure for excessive government paperwork is more government paperwork.

Those of us concerned about big questions of dysfunctional public policy design, rather than the real but incidental problem of paperwork, should turn from the concept of sludge to the concept of kludge. In National Affairs in 2013, Steven Teles published “Kludgeocracy in America.” According to Teles:

The term [kludge] comes out of the world of computer programming, where a kludge is an inelegant patch put in place to solve an unexpected problem and designed to be backward-compatible with the rest of an existing system … “Clumsy but temporarily effective” also describes much of American public policy today. To see policy kludges in action, one need look no further than the mind-numbing complexity of the health-care system (which even Obamacare’s champions must admit has only grown more complicated under the new law, even if in their view the system is now also more just), or our byzantine system of funding higher education, or our bewildering federal-state system of governing everything from welfare to education to environmental regulation. America has chosen to govern itself through more indirect and incoherent policy mechanisms than can be found in any comparable country.

An example of kludgeocratic policy in the United States is its retirement system, which Sunstein discusses in Sludge. Sunstein notes correctly that Social Security is a success because of the simplicity of its structure and administration, not merely the minimal paperwork that structure requires. In contrast, defined contribution programs like individual 401(k)s and IRAs are the very embodiment of dystopian kludgeocracy (my view, not Sunstein’s). Their value is unpredictable and depends on the state of the stock market in retirement, if savings are invested in mutual funds. Only a fraction of eligible workers take up offers by employers to contribute matches to employee savings. And mutual funds are notorious for hidden fees and misleading descriptions of their services.

By the logic of Telesian anti-kludgeocracy, the answer might simply be an expansion of Social Security, as my colleagues and I at New America (which published an earlier version of Teles’ essay) suggested a decade ago. Similar proposals have been made by Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren and other Democratic leaders. But most Democrats favor complicated, kludgey alternatives, like automatic enrollment of workers in IRAs, despite their inferiority to Social Security.

Why? One reason is mainstream Republican opposition to any expansion of Social Security. Another factor is neoliberal pro-market, anti-government ideology, summed up in Bill Clinton’s famous statement, “The era of big government is over.” Most important, perhaps, is the dependence of today’s Democratic Party on donations from Wall Street. Money managers can skim fees from tax-favored private savings accounts, but not from Social Security.

Compared to Teles’ powerful concept of kludgeocracy, which goes to the heart of our dysfunctional government, Sunstein’s discussion of sludge seems trivial—to use my favorite British word, it is twee. I hope that professor Teles will consider turning his 2013 essay into a pop nonfiction book titled Kludge, that it will lead to fame and fortune and be followed by two or three sequels each year, and that his publishers in their promotional copy will describe him as a “rogue political scientist” and “the most dangerous man in America.”

Michael Lind is a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.