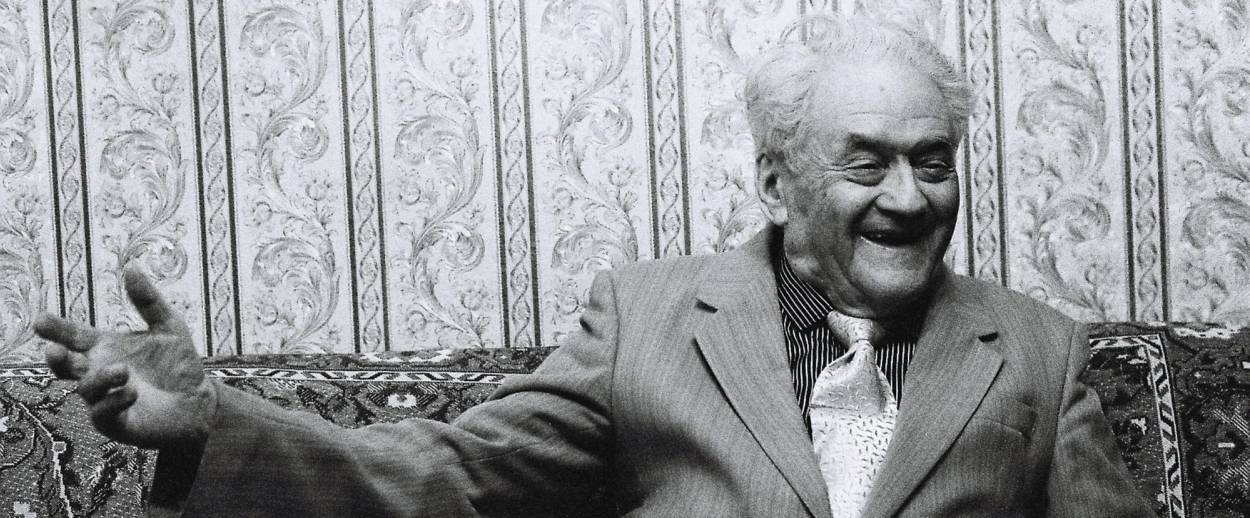

Arkady Gendler, a Paragon of the Yiddish Revival Movement, Dead at 95

Arkady, who lost his entire family in the Holocaust, was a ‘Yiddish rock star’

Arkady Gendler, who dedicated his life to Yiddish culture and music, has died at age 95. On its Facebook page, the Recording Arkady Gendler project remembered the musician thus: “The friendship, love, and generosity—not to mention the hours and hours of stories, jokes, and songs—that Arkady Gendler shared with us were as the warmth of the sun on a grey day.”

“May he be a likht in gan edn,” Yiddish New York wrote on its Facebook page; for lovers of Yiddish culture, evidently, he was already a light in this world.

In 2013, Tablet’s European correspondent, Vladislav Davidzon, wrote an arresting profile of Gendler, then 91, following a visit to his longtime home in Zaporozhye, Ukraine, “a grayish and sleepy industrial town.” He noted that the apartment Gendler had lived in since 1952 was “a jumble”—a marked contrast to his neat personal appearance. But Davidzon was most taken with Gendler’s voice—”gentle and firm, velvety cadenced and silky”—as befitting a Yiddisher zinger.

Davidzon delves into the story of Gendler’s life, beginning with his youth in Soroke (he later elegized his home in song), which was imbued with the sounds and colors of yiddishkayt, and perhaps set the stage for his later path:

The youngest of 10 children, two of whom died in childhood, he was doted on by his six older sisters. The family was learned and traditional, yet impious and progressive. “Ironically enough”—he employed the word often—“we were Romanian Communists!” Yiddish was spoken at home and Romanian outside of it. Despite crippling poverty, family life as he remembers it was idyllic, happy, and full of song. The Gendler children were all talented singers and constituted the core of the town’s Yiddish theater troupe, though formal education in a Romanian school had to be abandoned for lack of money when he was 11.

Here is Gendler singing “Mayn shtetl Soroke” (via the Recording Arkady Gendler project):

During World War II, Gendler served in an infantry brigade on the Ukrainian front. When he returned he learned that his entire family had been killed in the Holocaust. “The ironic part was that those of us who went up to the front all survived,” he told Davidzon (“with a bitter smile”). After the war, Gendler studied chemistry in Moscow for several years before moving to Zaporozhye, but his career took a major turn:

With the outbreak of Perestroika, which foreshadowed the swift collapse of communism of and Soviet empire, Gendler left the field of industrial chemistry and went to work in a Jewish school as a teacher of his beloved Yiddish. He was also able to sing Yiddish songs more openly. As the legend of the amateur Yiddish singer began to spread, he was invited to participate in Klezmer festivals and workshops in San Francisco and Copenhagen and Paris and Moscow. After the parting of the iron curtain, he emerged as the authentic missing archaeological link to the living roots of Yiddish culture.

A champion of Yiddish culture and the Yiddish revival, Gendler “is cherished by the specialists and oddballs who inhabit the musty, cultic, and tightly knit world of academic Yiddishkeit and Klezmer revival festivals.” As a relic of a nearly lost culture that more and more people are grasping for, Gendler was “the real real deal,” inspiring many a Yiddishist as the beacon of the culture they believed in. He was a friend of Itzik Manger, and “his syntax [was] on occasion reminiscent of the protagonist in a Saul Bellow novel.” But in addition to being “a living Alexandrine Library of Yiddish folklore, tradition, and song, much of it uniquely held by him,” as Davidzon wrote in 2013, he was “adorable” and charming, even capturing the hearts of women many decades his junior.

Read the rest of Davidzon’s profile here.

Miranda Cooper is an editorial intern at Tablet. Follow her on Twitter here.