Once Upon a Time in the Jewish Ghetto

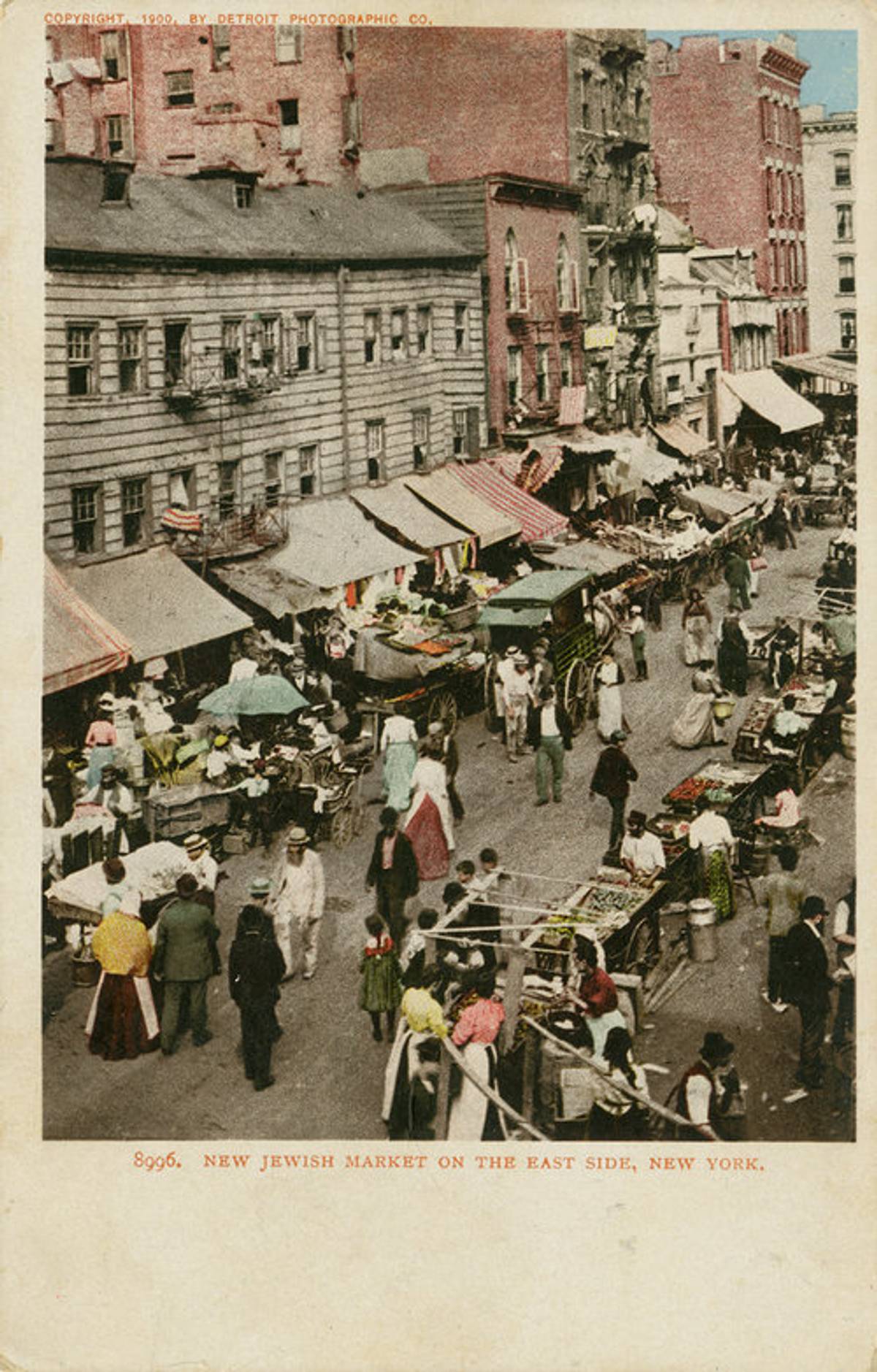

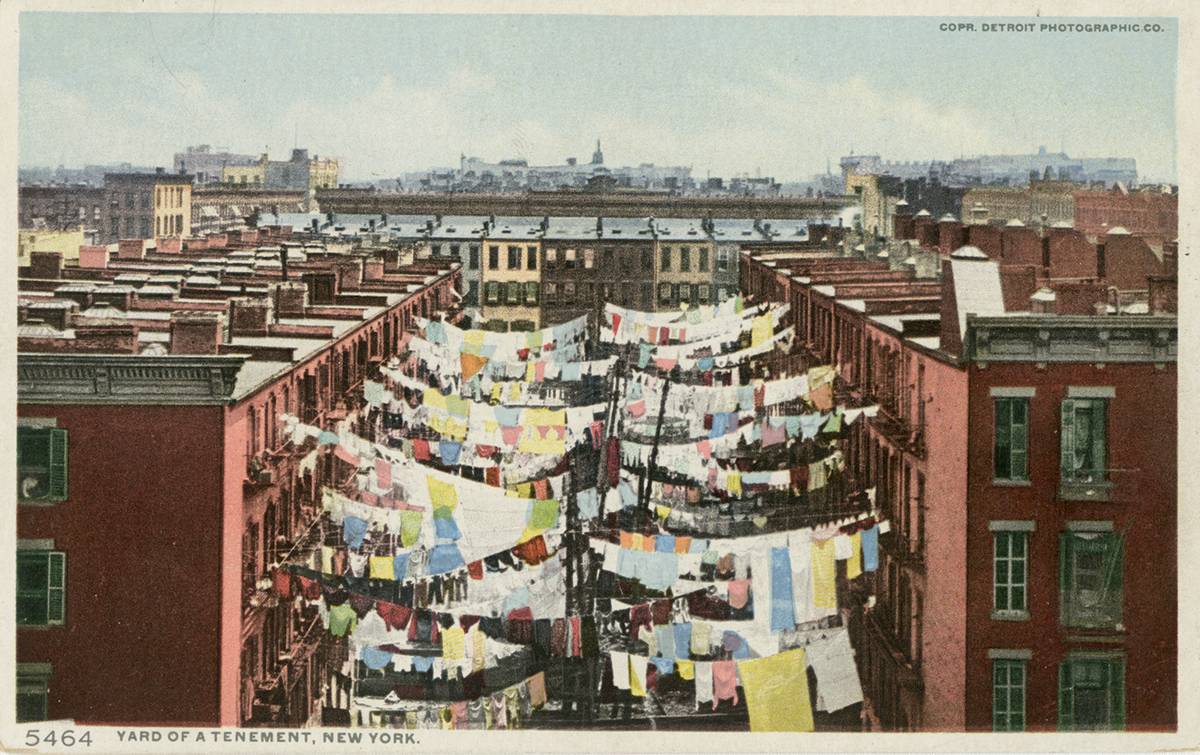

A new exhibit at the Museum at Eldridge Street showcases ‘The Jewish Ghetto in Postcards’

Fellow devotees of postcards and stamps! You can get a good fix at a nifty small exhibit at the Museum at Eldridge Street in New York called “The Jewish Ghetto in Postcards.” It presents cards from the Blavatnik Archive, a nonprofit foundation that preserves ephemera related to 20th century Jewish and world history.

Once upon a time, postcards were all the rage. “The Golden Age of the Postcard” was from 1905 to 1915—over 300 billion were produced in that decade alone. (One of my great joys is visiting thrift stores with boxes of old postcards; I have a nice little collection from the early 1900s of images of my home state of Rhode Island, and when I’m visiting family in Milwaukee, I look for postcards of old New York City, which are harder to find around these parts.) The earliest postcards had no room for a message; the recipient’s address took up the entire back of the card. People sometimes sneaked a cramped line of text into whatever white space they could find on the picture side.

For instance, a card in the exhibit, sent from a girl to her friend in Salem, Mass., in the early 1900s, depicts the crowded, chaotic streets of the neighborhood with a handwritten message in tiny writing under the buildings. “Dear Amanda,” it says. “How would you like to live in this neighborhood. It would be quite a change for you. Regards, Sophie.” In 1907, postal regulations changed, and you could write a note on the back of your card. Sophie could then send snarky commentary to Amanda at greater length.

This Golden Age of the Postcard dovetailed with the era of greatest immigration of Jews to America. “From 1880 to 1924, one-third of the Jewish population of Eastern Europe left shtetls and cities for the United States, fleeing persecution and seeking economic opportunity,” the exhibit’s wall text notes. The small show starts off with postcards of Eastern Europe and the shtetl, then moves on to similarly crowded and nostalgic depictions of the Lower East Side. The exhibit makes clear that such images were deliberately crafted to exoticize. “Today the idea of the shtetl looms large in the imagination of American Jews and is often infused with sentimentality,” the show notes. And the images of both the shtetl and the LES deliberately “reinforced cultural conceptions outside the community they depicted.” (Many of the cards portentously refer to the neighborhood as “The Ghetto”—with Other-izing initial capital letters, or “Judea.”)

Another section of the show pairs postcards with snippets of oral history from the museum’s collection that were recorded in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Next to a postcard of Ellis Island is a reminiscence from Gussie Dubrin about her three-week journey by sea in steerage, after which the island’s medics marked her sister’s apron with an X. It meant that her sister, who had poor eyesight, would be sent back to Eastern Europe. Dubrin’s mother reversed the apron to hide the X, and the entire family thus came to America. Another postcard trumpets, “Happy New Year!” and shows a bunch of religious Jews by the river, preparing to do tashlich. That one is paired with a memory from Max Smith, who became Bar Mitzvah in the shul in 1927: “We would stand outside the synagogue on Yom Kippur. During the middle of the day the adults came out…And they all fasted, but I was a kid and we wouldn’t fast at the time. We would sit there with a bunch of grapes, seedless grapes, and we’d say ‘Oh, are these delicious! They’re so juicy!’ They wanted to shoot us.”

Check the museum’s schedule for events connected to the exhibit: There’s a talk with Annie Polland of the Tenement Museum focusing on women’s roles on the Lower East Side, a “Tenement Songs: Popular Music of Jewish Immigrants” sing-along, a family event in which your kids can walk to Hester Street and look for buildings they see in the old postcards, then hit the penny candy store, and finally come back to the museum to create their own postcards. Epistolary fun for all!

Marjorie Ingall is a former columnist for Tablet, the author of Mamaleh Knows Best, and a frequent contributor to the New York Times Book Review.