An Open Letter to Incoming Students

Campus Week: Your guide to navigating the personal and political minefield of today’s hypersensitive college life

This article was originally published on Sept 20, 2016, and is presented here for Campus Week 2018.

Welcome to campus. When I say “campus,” I mean “campus,” from the Latin, “field.” A campus is the kind of place where people will tell you the etymology of “campus” whether it matters to you or not.

Today, lots of institutes claim to have “campuses.” Facebook, Google, and Apple do. What they mean is a sprawl of fairly new buildings separated by lawns, walkways, and monuments of sundry merit, but more—they wish to convey the grander idea that the pursuit of knowledge goes on here, along with amenities like gyms, cafeterias, and snack bars. They offer all manner of clubs to join, or ignore, or dislike, if not organized teams. There’s sometimes a suggestion, at least, that transcendence may be pursued here. (I see that Apple’s address is 1 Infinite Loop, Cupertino, California.) There’s an official (at least) belief that what goes on here is for the good of humanity. Nobody needs to be told that bonuses and stock options accrue along the way.

Our kind of campus not only usually has fields (in the grassy sense) but contains fields—all kinds of fields. We also believe that what we’re doing is for the common good, and at the same time that what we do is good for us as individuals. You may or may not run into people who study Latin, Yiddish, astronomy, molecular biology, mechanical engineering, social history, law, social work, hotel management, Chinese or Mexican or African-American history, etc., etc. There’s not so much agreement as there used to be on what constitutes basic knowledge. (It was easier to agree when campuses were far fewer and far more exclusive, and cultivation was a singular noun.) There isn’t (usually) a profit motive to supply a common purpose. But periodically you will be reminded that you are here to think, learn, and rethink.

Our campus contains not only fields but silos. It also mixes and matches. Old fields dwindle, or subdivide, or evolve, or conflict with other fields. This can be confusing. It’s not unambiguously clear what is a good thing to study and how to study it. Sometimes there are nasty disputes about what counts as knowledge. This is not like, say, a baseball field, where everyone agrees on the rules. But this is also a place where ground rules of respect apply, and people are not presumed to be nothing other than signposts on which they bear identity cards.

People learn on campus, or try to, and some fail. Some have to learn to learn. Sometimes they dispute the meaning of “learn.” Some learn what they’re told will help them get good jobs or even careers. Some don’t know what kind of job or career might be good for them, or for the world, and some change their minds. You’ll hear a lot about something called the job market. Some of you will graduate knee-deep in debt, and spend years trying to dig out. Some will take fancier vacations than others; some will take no vacations at all. Some campuses enjoy higher prestige than others. You’re welcome to think whatever you like about all these matters, and to worry and argue about them. Attacking what people say because of what you consider their deficiencies or their privileges is not acceptable. You’ll have plenty of time in your lives for that.

The campus is also a place that throws disparate people together. It may well offer more (or more varied) sexual opportunities than you’ve encountered before. This can be wonderful and confusing. Because the campus is also a place where hundreds or thousands or even tens of thousands of human beings congregate—and many of them have never before lived away from home—horrible things happen. There are rapes. There is nastiness. There are racist and homophobic slurs, and occasionally worse. People get up in each other’s faces. Often they don’t know whether the campus is supposed to be a rigorous and impersonal zone or whether it is supposed to be homey (thus “comfortable,” and “safe” from “microaggressions” committed by people who are, some way or other, different). Sometimes the world from which they came is a hellhole, and they struggle with what to do about that, or how to relate to people they know who are still there. Empathy is a good idea. But we do not staff the campus with empathy police.

Whether there’s more bad conduct on campus than elsewhere in the society is highly doubtful, but news about depredations and crimes on campus tends to spread further and faster than news about off-campus depredations. Partly this is because the people who publish news have almost all spent time on campuses and tend to look back fondly on that time, and so they’re prone to be shocked that bad things happen there. The campus is obliged to do its utmost to protect you from crime. It cannot protect you from most of the shocks of living.

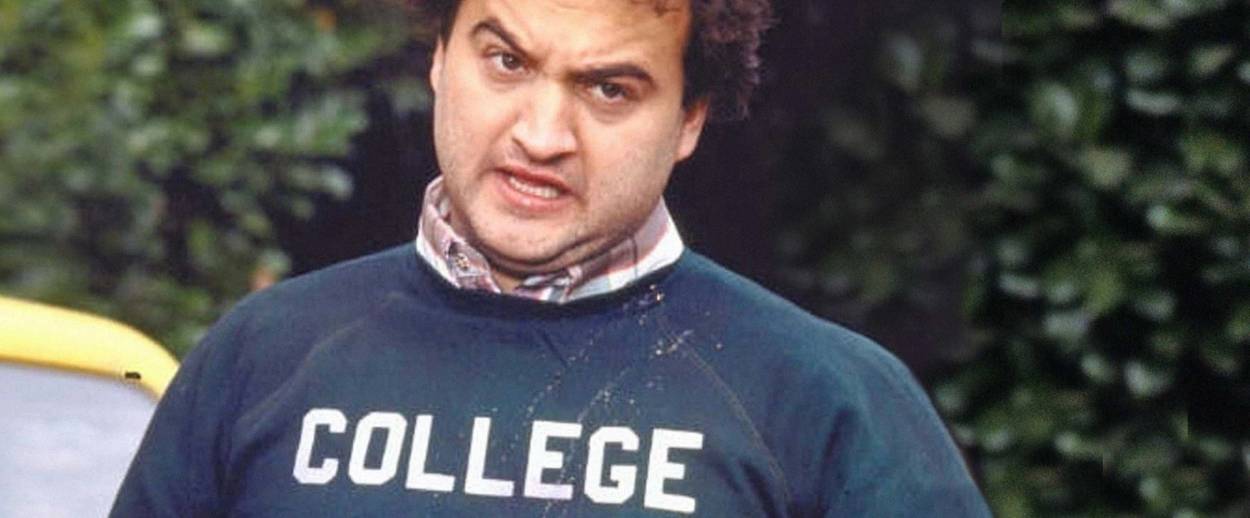

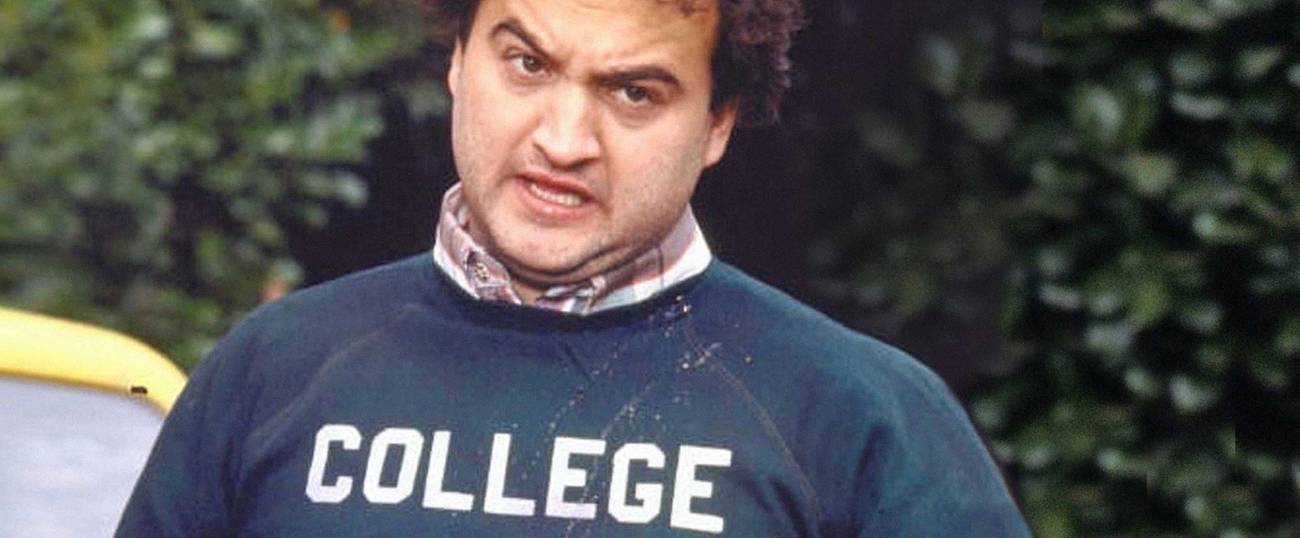

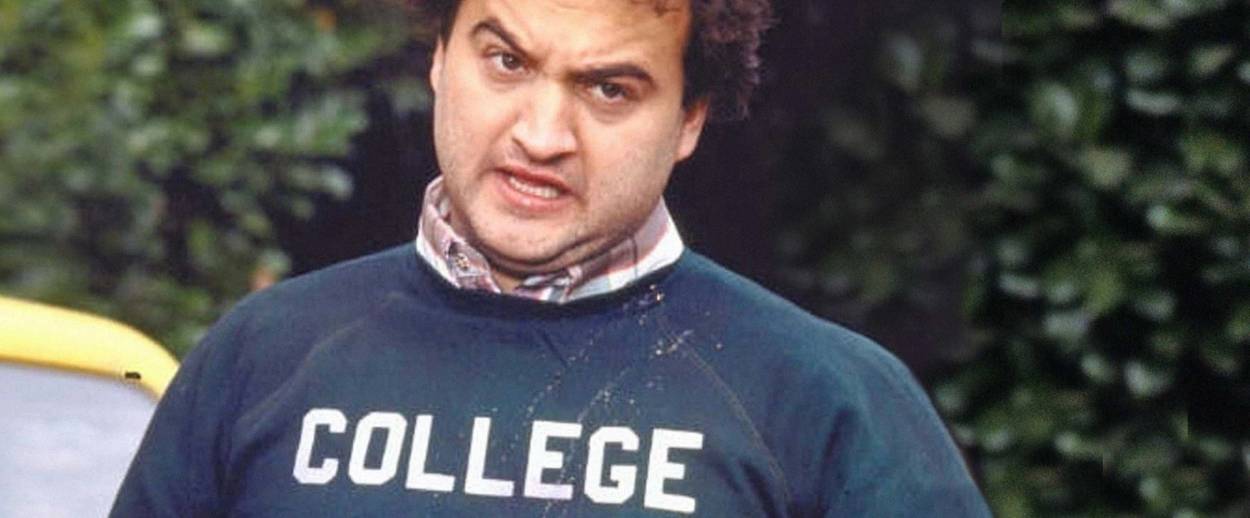

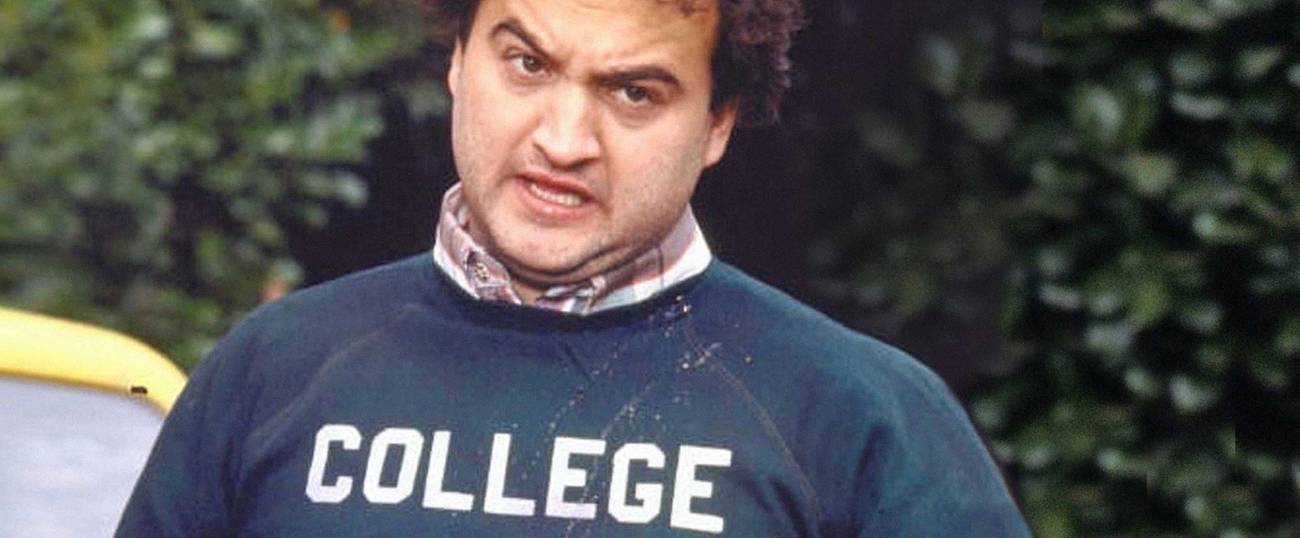

Another reason the bad news spreads is the larger culture—when it’s not angry at universities because they cost too much or because the people who pass through the gates can be seen as snobbish—harbors a residual reverence for the place, a feeling cultivated by development offices everywhere. The look of many colleges is conducive to fantasies of a bucolic nature. So is the sound of the place—there tends to be less street noise than elsewhere, and voices are rarely raised in public. People on campus tend not to rush around on motorized vehicles. (The Halls of Ivy was once an anodyne sitcom rife with quaintness.) Symbolically, the campus is often a locus for superiority but at the same time a subject of mirth (Animal House).

You may well have heard that campuses have become scary places. Don’t prejudge the matter. Horror stories make for exciting news, and again, exciting news carries. But you may face disturbing moments. (There are no guarantees.) During your years here, you may well encounter someone or something—a teacher, a fellow student, a text, a poster, a picket sign—that disconcerts or even enrages you. Some teachers are skilled at conveying knowledge, at eliciting fruitful conversation; some are not, or approach disputes differently. Some hold one or another prejudice. Most of them have learned to keep their prejudices under wraps; some have not. Most of the time there’ll be no warning before an unwelcome sight. The world you graduate into will be like that, too. Unless someone has confronted you with physical abuse, you have to learn to live with it without summoning a police power. If you feel bad after you hear something or read something, don’t assume that you’ll be traumatized forever by the experience. The odds are very strong that you won’t be.

The thing about universities is, like the rest of society, they encompass all kinds of people. What should you do if somebody else’s view scares or unsettles you? As we say in New York City, if you see something, say something—to the one who scared or unsettled you, or to others. Try to clarify what just happened. Try to explain why you feel what you feel. Use sober judgment. See what happens. You don’t need to appeal to higher authority. But if you don’t get a respectful response, and you can see no other way to address what you think is a wrong being done to you, then appeal to professors, deans, or other officials.

What should you do if somebody demonizes you or prevents you from speaking in accordance with your beliefs? No one has a right to silence you. They have the right to disagree, not to stifle you with a conversation-stopping insult or a threat. If this happens in class, bring the demonization, silencing, or threat to the teacher’s attention. If it happens outside class, find the authorities. It’s their job to expedite respectful conversation.

What if the person in question is a teacher? Protest. It is wholly illegitimate for a teacher to punish you for your objection. If you think this is happening, and the teacher in question is immovable, then bring the matter up with the chairperson of the department.

What if your opinions make you unpopular? Them’s the breaks. You have no right to be popular. You are in school not to be popular, and deprivation of popularity is not a crime.

You’re here to think. Thinking is hard and often (not always) fun. Thinking is unsettling. You’re here to be unsettled—not by being told you’re a member of any particular tribe of human beings, not by being physically accosted, but by being challenged to investigate the grounds of beliefs—yours and others’. You’re here to be disagreed with, but not because of who you are.

You’re here to respect evidence and logic. Challenging someone else’s opinion is a perfectly good thing to do. Insisting that others think what you think without evidence and logic is not acceptable. Insisting or insinuating that someone should be disrespected because of color, nationality, accent, disability, religion, or sexuality is not conducive to learning. Don’t do it. And object when others do it.

Be curious. When authorities disagree, be curious about why. Try to find out not just what you think, or what people you think are like you think, but why—and why other people have the irritating habit of thinking differently. Try to understand why bad things happened in history, and what might be concluded from that fact.

This place is not your living room but it is not a free-for-all, either. You’re likely to run into words or even conduct you think is wrong or even offensive. If somebody says or does something that troubles you, or offends you, or outrages you, discuss that with him or her. See what you can learn from the conflict. Politeness will get you somewhere. If you find anger spilling out, even aggression, talk about that, too. You have a right to protect yourself. You also have the right to a total campus environment where coexistence, contradiction, and diversity of color, nationality, and belief are essential for the common good.

Physical violence is never acceptable. Period.

Keep your wits about you. Expect the unexpected. That’s why you’re here.

Have a ball.

***

To read more from Tablet magazine’s special Campus Week series of stories, click here.

Todd Gitlin (1943-2022), was a professor of journalism and sociology and chair of the Ph.D. program in Communications at Columbia University, and the author of among other books The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage; Occupy Nation: The Roots, the Spirit, and the Promise of Occupy Wall Street; and, with Liel Leibovitz, The Chosen Peoples: America, Israel, and the Ordeals of Divine Election.