Our Weaponized Legal System Misfires

How partisan lawfare threatens democracy

The greatest threat to democracy today is not populism, as elite liberals claim. Nor is it the old-fashioned dictatorial coup d’etat. The greatest danger that multiparty democracy faces is “lawfare”—the weaponization of national judicial systems by political parties to delegitimize, harass, bankrupt, disqualify, and sometimes imprison politicians of other parties.

In Scotland, the husband of former Prime Minister Nikola Sturgeon has been arrested in a case involving Scottish National Party finances; soon she may be arrested herself. In India, opposition leader Rahul Gandhi has been arrested and sentenced to two years in jail and expelled from parliament for joking about the name of India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi. In Pakistan, former Prime Minister Imran Khan has been arrested, with Pakistan’s Supreme Court holding that his arrest by paramilitary forces was unconstitutional. In Brazil, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva was recently elected president, after having been arrested and imprisoned on corruption charges, only to have the verdict thrown out by a judge. In 2018, half of all former living South Korean presidents were in prison.

Latin America, sharing separations-of-powers constitutions like the U.S., leads the world in impeachments of presidents by opposition parties carrying out “legislative coups.” Of 12 impeachments in Latin America since 1900, 10 have taken place in the last three decades and six in only three nations—Brazil, Ecuador, and Paraguay.

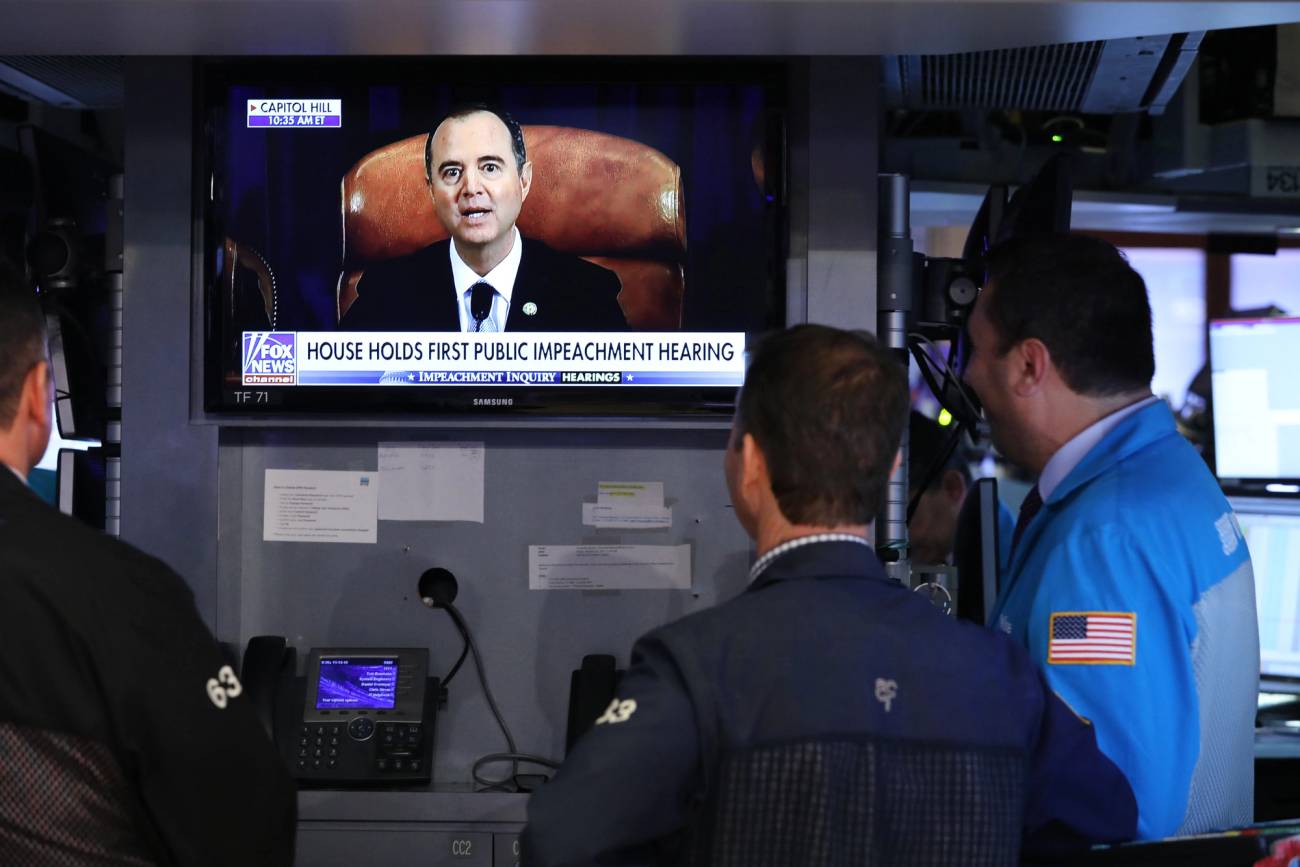

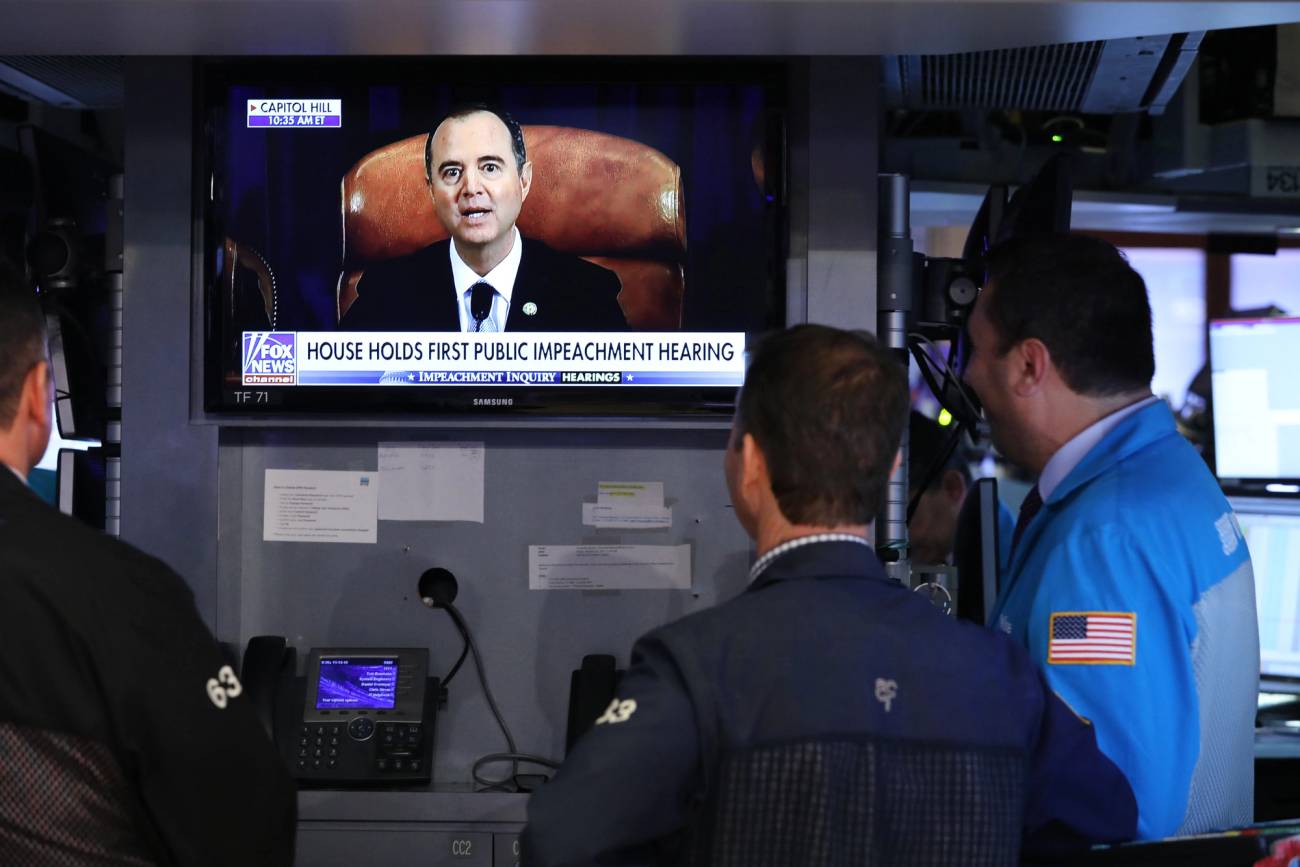

In the 235 years in which the U.S. has been governed under the federal Constitution, three of the four presidential impeachments have taken place in the last 25 years, and two in the last three years. In North America, as in Latin America, impeachment has gone from being the last resort in emergencies to being a frequently used weapon by one political party against another.

Has any U.S. president ever deserved impeachment? Yes, one: Richard Nixon.

Nixon’s Special Investigations Unit, known as the Plumbers, had originally been created to spy on opponents of the Vietnam War. On June 17, 1971, Nixon told his aide H.R. Haldeman he wanted the Plumbers to obtain files that might be in the safe of the Brookings Institution that could show that his predecessor, Lyndon Johnson, had ordered a bombing halt in Vietnam to help Nixon’s Democratic opponent in 1968, Hubert Humphrey. Nixon wanted to use the files to blackmail Johnson.

Nixon: “Did they get the Brookings Institute raided last night? No?”

Haldeman: “No, sir, they didn’t.”

Nixon: “Get it done! I want it done!” (banging desk for emphasis) I want the Brookings Institute safe cleaned out, and have it cleaned out in a way that makes somebody else” (unclear).

On July 1, Nixon returned to the theme in a meeting with Haldeman and Henry Kissinger:

Haldeman: “You could blackmail [Lyndon] Johnson on this stuff, and it might be worth doing. …

Nixon: “Bob? Bob? Now you remember Huston’s plan? Implement it.”

Kissinger: “Couldn’t we go over? Now, Brookings has no right to have classified documents.”

Nixon: “I mean, I want it implemented on a thievery basis. Goddam it, get in and get those files. Blow the safe and get it.”

Brookings was never burglarized and the safe was never blown, but the Plumbers later burglarized the Watergate Hotel in search of Democratic Party secrets, leading eventually to Nixon deciding to resign before he could be impeached. I think most people of all parties would agree that a president who uses a private gang to burglarize the offices and hotel rooms of his opponents is indeed guilty of “high crimes and misdemeanors.”

In contrast to the possible impeachment of Nixon, the impeachments of Andrew Johnson and Bill Clinton, and the two impeachments of Trump, were unjustified exercises of partisan power. Andrew Johnson was a terrible president, but the radical wing of his own Republican Party impeached him because they opposed his Reconstruction policies, not because he committed any “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky and his perjury in concealing it; Trump’s clumsy attempt to get Ukrainian President Zelensky to supply him with incriminating evidence against Hunter Biden; the inflammatory effect of Trump’s claim that the election had been stolen in inciting the unforeseen January 6 riot (not “insurrection”)—all of these deserved the harsh penalty of censure by Congress, but not the nuclear weapon of impeachment and removal from office.

A more serious charge arises from Trump’s recorded phone call to fellow Republican Brad Raffensburger, Georgia’s secretary of state, asking him to “recalculate” to “find 11,780 votes.” Raffensburger refused, as the state had already done three separate ballot counts and two certifications of Biden’s victory.

Even with Georgia’s electoral votes, Trump still would have lost the electoral college to Biden. Trump failed to persuade officials in other states, as well as Vice President Pence and other leading Republicans, to take steps to delay or overturn the certification of Biden as president. From this distance in time, Trump looks less like the mastermind of a plausible scheme to overturn the election and establish a dictatorship than an incompetent, pathetic narcissist who genuinely believed that he had been cheated out of a second term and listened to cronies who fed his delusion.

Even after the riot on January 6, six Republican senators and 121 Republican House members objected to certifying the electoral outcome in Arizona, while seven Republican senators and 138 House Republicans objected to certifying the results in Pennsylvania.

This was a disgraceful stunt, but it was an escalation of what had become the normal practice of both parties for years. In January 2005, House Democrat Stephanie Tubbs Jones of Ohio and California Sen. Barbara Boxer, also a Democrat, objected to the certification of Ohio’s electoral votes, claiming: “We believe there are ample grounds for challenging the electors from Ohio as being unlawfully appointed.” If their motion had succeeded, all 20 Electoral College votes of Ohio for George W. Bush would have been denied and with neither candidate having an Electoral College majority the election would have been decided by the House of Representatives. Although the effort failed, 32 members of Congress, all Democrats, voted for this attempt to overturn the presidential election of 2004.

On Jan. 6, 2017, the following seven Democrats in the House objected to the certification of the electoral count: Jamie Raskin, D-Md., (objecting to Florida’s votes); Jim McGovern, D-Mass., (objecting to Alabama’s votes); Pramila Jayapal, D-Wash., (objecting to Georgia’s votes); Raul Grijalva, D-Ariz., (objecting to North Carolina’s votes); Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, (objecting to votes from North Carolina, South Carolina, Wisconsin, and Mississippi; Barbara Lee, D-Calif., (objecting to Michigan’s votes); and Maxine Waters, D-Calif., (objecting to Wyoming’s votes).

Several of these Democrats objected to congressional certification of the 2016 election on the basis of conspiracy theories. Barbara Lee alleged Russian manipulation of the election and malfunctioning voting machines. Sheila Jackson Lee claimed there had been “massive voter suppression” in Missisippi. All were overruled by then-Vice President Joe Biden in 2017, in the same way that Vice President Mike Pence overruled similar objections in 2021.

One of the Democrats in the House who tried to stop the certification of the election in 2016 on spurious grounds, Jamie Raskin, went on to be the lead impeachment manager in the second impeachment of Donald Trump.

Impeachment has gone from being the last resort in emergencies to being a frequently used weapon by one political party against another.

Having lost the election of 2020 and returned to private life, Donald Trump is now the most likely opponent of Joe Biden in the presidential election of 2024. Trump continues to be the victim of Democratic lawfare. Attorney General Merrick Garland authorized a theatrical ransacking of Donald Trump’s home by FBI agents to collect classified documents during a dispute over ownership—shortly before it was learned that President Joe Biden also had possessed classified documents, from his days as vice president.

Now Alvin Bragg, the elected district attorney of New York City, has had Trump arrested and indicted. Trump is charged with falsifying business records while legally paying hush money to Stormy Daniels, a porn star with whom he had an affair. By an extreme stretch of the imagination, Bragg claims this violated campaign finance laws. Even so, normally this would be a misdemeanor, punished by a fine. For example, in 2022, the Federal Election Commission fined the Democratic National Committee and the Clinton campaign more than $100,000 for disguising payments to Fusion GPS, the opposition research group behind the pro-Clinton “Russiagate” hoax that claimed Trump was a witting or unwitting Russian asset, by claiming falsely that the money was for legal expenses incurred by the law firm Perkins Coie.

But Bragg, instead of seeking to fine Trump for similar campaign finance violations, has promoted 34 charges to felonies. If convicted on all 34 counts, Trump could face a maximum sentence of 136 years.

Cy Vance, Bragg’s predecessor as DA, refused to charge Trump on such flimsy grounds. His refusal infuriated many Democrats who welcome Bragg’s prosecution of Trump as revenge, pure and simple, for Trump’s defeat of Hillary Clinton in 2016 and the failure of the two unjustified impeachments of Trump by partisan Democrats in the House. Campaigning for election to the post of district attorney, Bragg boasted: “I have investigated Trump and his children and held them accountable for their misconduct with the Trump Foundation. I know how to follow the facts and hold people in power accountable.” This sounds very much like a campaign promise to voters in overwhelmingly Democratic New York City to find some excuse, any excuse, to use the power of the District Attorney’s Office to try to imprison a former president they despised.

“Whataboutism” is a perfectly valid argument, when it is proof of a double standard. For most Democrats, Bill Clinton’s perjury about his affair with Lewinsky was “just about sex” and blown out of proportion to the offense. And yet Trump’s hush money payment to Stormy Daniels, many Democrats tell us, threatened democracy itself by somehow subverting the 2016 presidential election.

In yet another case in overwhelmingly Democratic New York, a federal jury found Trump innocent of a charge of raping E. Jean Caroll, while finding him guilty in a civil trial of defamation and sexual abuse and ordering him to pay a fine of $5 million. Assuming that Trump was guilty on these lesser counts, perhaps Alvin Bragg or other Democrats can come up with a creative theory why this incident, like the Stormy Daniels incident, threatened American democracy.

For his part, Trump has often threatened to wage the kind of lawfare to which he has been subject by Bragg and other partisan Democrats abusing the powers of their office, like former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi and the House Democrats who thrilled their voters by impeaching him twice. In a presidential debate on Oct. 9, 2016, on live television, Trump told Clinton: “If I win, I am going to instruct my attorney general to get a special prosecutor to look into your [missing email] situation, because there has never been so many lies, so much deception.” When Clinton replied, “It’s just awfully good that someone with the temperament of Donald Trump is not in charge of the law in our country,” Trump interjected: “Because you’d be in jail.”

During campaign rallies, Trump smiled as his followers chanted “Lock her up!” and at one point he told a crowd: “She has to go to jail!” All of this over Clinton’s use of a private email server during her service as U.S. secretary of state, a minor security breach and a misdemeanor of a kind which in most cases the government has chosen not to prosecute.

When I raise my concerns about the increasing resort by both parties to lawfare as a substitute for regular electoral politics in the U.S., I am sometimes told that nobody is above the law. But this is a facile answer, for two reasons.

The first has to do with legal complexity and ambiguity. Many of the politicians who have been attacked by their partisan rivals with the weapons of lawfare have been ensnared by charges of corruption in campaign spending. I do not claim to be an expert in U.S. campaign finance laws, much less those of Israel or South Korea. But the campaign laws in our country and many others are so complex and vague that any clever prosecutor might be able to indict any politician. Hush money payments to keep an extramarital affair out of the press constitutes election interference? Really, Mr. Bragg?

Moreover, some abuses of office in return for donations are perfectly legal in the United States. For example, all presidents appoint a number of rich campaign donors or bundlers, many of them utterly unqualified, to ambassadorships. Joe Biden has given around a third of ambassadorial appointments to donors. Isn’t this … selling offices? And if so, this routine practice is not so different from the corruption of former Illinois Gov. Rod Blagojevich, who was impeached by the Illinois legislature and sent to prison for, among other things, plotting to “obtain a personal benefit in exchange for his appointment to fill the vacant seat in the United States Senate [left by President-elect Obama].” If former President Obama is not in prison for appointing 31 campaign “bundlers” who each raised $50,000 or more and who together raised more than $20 million for Obama’s campaigns to cushy ambassadorial posts in Western Europe, Canada, and New Zealand, why was Blagojevich’s sale of Obama’s Senate seat—as distinct from his other misdeeds—a crime? (In 2020, President Trump commuted Blagojevich’s 14-year sentence after eight years in prison.)

Another form of perfectly legal corruption in the United States involves ex-presidents being paid enormous sums for speeches by special interests that may have benefited from their policies while in office. In 1989, former President Ronald Reagan reportedly earned $2 million from a Japanese media conglomerate for a speech and tour of Japan.

Hollywood and Wall Street are major donors to the Democratic Party and they see to it that former Democratic presidents get rich quickly. After serving in the White House, for example, Barack Obama made $1.2 million for only three Wall Street speeches. He and former first lady Michelle Obama were given lucrative deals to produce TV shows and films with Netflix and podcasts with Spotify through their company Higher Ground Productions, hastily founded for that purpose in 2018. How is this any different from the former head of a congressional committee or a former executive branch regulator immediately being hired or otherwise paid off by the industry he or she regulated?

I am not arguing that Barack and Michelle Obama should be locked up, though they should be shamed for their blatant buck-raking. My point is that, just as it is hard to make sense of American campaign finance laws, there seems to be no logic to which certain kinds of pay-to-play deals and payoffs for services rendered are legal in this country and which can lead to jail time. It follows we should be skeptical about corruption charges along with alleged campaign finance violations, particularly when a partisan political motive is behind a prosecution.

The second reason that the phrase “nobody is above the law” is a trite answer that evades serious questions has to do with legitimacy. When I have taught courses on politics, I have asked students: What is the purpose of multiparty democracy? To achieve justice? No, I suggest, it is to avert civil war, by exchanging ballots for bullets. If elections are thought of as bloodless civil wars every few years, then the losers must be conciliated and made to feel that they remain valued members of the national community and that they have a chance to win next time. If each party portrays the other as an enemy to democracy and society, and the winners use the court system to bankrupt and jail opponents in attempts to prevent the losers from winning elections in the future, then the legitimacy of the democratic system will collapse.

Here we can learn lessons from actual civil wars. Thanks to President Andrew Johnson’s 1868 proclamation “granting full pardon and amnesty for the offense of treason against the United States during the late Civil War,” only two Confederate soldiers were executed for crimes committed during the war, Henry Wirz, commandant of the notorious Andersonville prisoner of war camp, and a Confederate guerrilla, Henry “Champ” Ferguson. Both Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate army, and former Confederate President Jefferson Davis were pardoned as part of Johnson’s amnesty, even though the rebellion they led had caused the death of more than 600,000 Americans—more than died in the world wars, the Korean War, the Mexican-American War, the Spanish-American War, the War of 1812 and the War of Independence, combined.

Abraham Lincoln almost certainly would have approved of his successor’s amnesty. In Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, Lincoln’s bodyguard Ward Hill Lamon related the following story:

General Grant asked for special instructions of Mr. Lincoln, whether he should try to capture Jefferson Davis, or let him escape from the country if he wanted to. Mr. Lincoln related the story of an Irishman who had taken the pledge of Father Matthew, and having become terribly thirsty applied to a bar-tender for a lemonade; and while it was being prepared he whispered to the bar-tender, ‘And couldn’t you put a little brandy in it all unbeknownst to myself?’ Mr. Lincoln told the general he would like to let Jeff Davis escape all unbeknown to himself; he had no use for him.

Partisan prosecutions need to be condemned by all civic-minded Americans now. Otherwise, Republican versions of Alvin Bragg all over the country may soon appear and start suing former Democratic officials now in private life. American democracy may die, not all at once in a coup d’etat, but slowly as the result of party-driven legislative impeachments and vengeful partisan lawsuits.

Michael Lind is a Tablet columnist, a fellow at New America, and author of Hell to Pay: How the Suppression of Wages Is Destroying America.