Paul Berman’s Crisis Notebook

A collection of pandemic jottings from Tablet’s News-section column ‘Modern Times’

Editor’s Note: Paul Berman has been keeping a notebook on the crisis, and Tablet has published tiny passages from it every two or three days since the crisis began. You can find the passages in Tablet’s News section under the rubric Modern Times. From time to time we will collect the recent passages and publish them as a group.

An early symptom of COVID-19, it is said, is a loss of the sense of taste and smell—and, in this respect, the city as a whole has fallen ill. The exhaust fumes are gone, except for the streaky odors of an individual car as it rolls by. The human cloud no longer wafts up from the sidewalk. It might be supposed that, under those circumstances, the ancient forests and their own aromatic scents must be plotting a comeback. But not in my part of town. I hear the chirping of sparrows, now that silence rules the streets. But, on my block, the grassy patches and weeds and the trees are scarce, and the pavement and the bricks emit no aroma at all. Instead of something, there is nothing. Nothing is horrifying—a sentence which, in the time of the coronavirus, means the opposite of what it would normally mean.

Every large event in recent world history has been a colossal shock. No one predicted the collapse of Communism and the Soviet Union—not really, even if a handful of people claimed to have done so, after the fact. Nor did anyone predict Sept. 11 and the rise of a mass religious movement for suicide and terrorism. Nor did anyone predict the election in America of a genuine charlatan—the first president in more than 230 years to lack even the appearance of professional qualifications. The charlatan himself was amazed.

And no one predicted the pandemic. Or rather, any number of scientists predicted such a thing, and drew up federal protocols, and founded suitable institutions, under the auspices of the Pentagon and the Department of Health and Human Services. But when the virus arrived, the protocols were abandoned and the new institutions proved to be unprepared—in testimony to the reality that, at the pinnacle of American society and perhaps in other places, as well, the predictions were never really taken seriously.

The modern style, then, is to stumble through the events of history not just blindfolded, but repeatedly astonished to learn that we are blindfolded.

Horn-honking came to a halt in the streets of Brooklyn in the weeks after 9/11, and horn-honking came to a halt in those same streets at the very start of the epidemic, even before the beginnings of lockdown. Thus a lesson about city life. We imagine that horn-honking expresses impatience, but it does not. Horn-honking expresses exuberance. At moments of catastrophe we are just as impatient as before, or more so. We still want people to get out of the way. But we no longer feel the desire to say “Long live noise!” and the honking ends.

Sirens are a different matter. A friend in Milan, quarantined and segregated within his own apartment, tells me that, in his city, ambulances are making the only sound to be heard. Not so in Brooklyn right now. There are no sirens, not yet. It was different on the morning of 9/11, when sirens wailed constantly in hideous cacophony.

Whittier’s poem “Snow-Bound” impressed me as a child, even if I did not understand it. I thought it was a quaint set of vigorous rhymes about being stuck in a farmhouse with the family and a couple of guests in a marvelous blizzard. The parts about the snow and the beasts in the barn pleased me no end. But today I see that “Snow-Bound” is a meditation on what happens to time, when you are stuck in confinement. Events no longer occur in the present, when you can no longer leave the house. In the housebound world, events are ones that are remembered from long ago, and are recounted to beguile the tedious hours.

These are the father’s memories, the mother’s, the uncle’s, the aunt’s, and the memories of the schoolmaster who happens to be visiting. They are memories of America—the persecution of the Quakers long ago, and the terrors of the Indian Wars, and the treason of the Southern slave masters and the war against them. Memories of hardship. Then again, the entire poem is itself a memory recollected in later life, somberly observing that all of those beloved snowbound storytellers have departed to the other world. A nostalgic poem, sentimental, cozy and morbid. To be confined to the house, then, driven there by the hostility of nature—this is to be driven into memory of the larger society and its past, and into the memory of your own intimate past, and into contemplation of the eternal.

Everybody agrees that, post-crisis, the world will veer in novel directions, and I enjoy reading the speculations on this theme by clever people. Michael Klare in The Nation, for instance, figures that, after everything that has happened, the United States will be driven back to the Western Hemisphere, as in the 19th century. Especially I enjoy the speculations of Anne-Marie Slaughter in the Times, who figures that, in spite of the president, American ingenuity will have its triumphs, and the culture will make a decisive turn toward the internet, whose virtues will burst into bloom.

I would like to come up with futuristic ruminations of my own. The many hours that I have spent studying Hegel, not to mention Fourier and Kropotkin, ought to have prepared me to be clairvoyant on the coming stage of history. But my heart is not in it. I worry, instead, about the spooky silence on the streets. How long will it be until the hysteria of ambulance noise erases the silence completely? The obstacle to contemplating the coming stage of history is, in sum, the present stage of history.

Alexander Pope maintained that “Whatever is, is right,” or more punchily, “All is good.” But, in 1755, the city of Lisbon was destroyed by an earthquake, and Voltaire, who loved Pope, but was exasperated by him, composed his “Poem on the Disaster of Lisbon” to explain that all is not, in fact, good.

The poem was a demolition of the idiot optimism that believes that all is good right now. It was a demolition of the idiot fatalism that believes that all is good in the light of eternity, even if not right now. It was a demolition of the belief that history conforms to moral law, and people get their just deserts, and all is good from a moral standpoint.

The poem was a recognition that evil exists, and, being evil, has no logic. It was a call for compassion. It was a defense of hope—not because hope is necessarily realistic, but because it is a human necessity. Voltaire pictured the people of Lisbon, crushed under the marble debris, crying out for Heaven to save them. And he disdained anyone who would sneer at those people.

Voltaire was great because he understood that, on Earth, no one and nothing are in charge, which is terrifying. He understood that, even so, there is a need for someone or something to be in charge. And he was angry at anyone who, like the mighty Alexander Pope, fails to see and articulate those contradictory and human and inhuman truths.

Camus, in The Plague, explains that Doctor Rieux’s uncertainty at the first sign of plague can be justified: “Epidemics, in fact, are a common thing, but we have trouble believing in them when they fall on our heads. There are as many plagues in the world as there are wars. And, however, plagues and wars find people equally off guard. Doctor Rieux was off guard, as were our fellow citizens, and it is in this fashion that it is necessary to understand his hesitations. It is necessary to understand in this fashion that he was torn between worry and self-confidence. When a war breaks out, people say: ‘It won’t last, it is too stupid.’ And doubtless a war is very stupid, but that doesn’t prevent it from lasting. Stupidity insists on having its way, and we would see it if we weren’t always thinking about ourselves. Our fellow citizens in this regard were like everyone, they were thinking about themselves. In other words, they were humanists. They did not believe in epidemics. An epidemic is not at the measure of man. We tell ourselves that it is a bad dream, and it will disappear. But it does not always disappear, and, from bad dream to bad dream, it is men who disappear, beginning with the humanists, because they have not taken their precautions.”

So says Camus. He has identified me completely. The coronavirus seems to me beneath my dignity—unlike, say, terrorists and crazed fanatics. Surely a stupid virus cannot be a huge problem! But it turns out to be a huger problem than terrorists and fanatics.

It is odd to notice how lovely is the warbling of a bird somewhere above the broad avenue. Of course I do not know what kind of bird. I am a city man. How should I know? An operatic bird, I would say. A bird with solid voice projection, and a florid vibrato. But mostly it is odd to notice how vivid is the warbling, against the near-silence of the streets—not loud like a car-honk, but then, because car-honks are a thing of the past, a warbling that might well be as loud. I wonder about the bird himself—I picture it as a he-bird—and what he thinks of his own voice, suddenly so powerful. And what is he saying? Is he calling for his mate, the she-bird? Is he speaking of death and the eternal, as in a poem by Whitman? Maybe he is merely testing how penetrating his vibrato can become. Does he recognize that, because of the sudden disappearance of competing noises, his warbling may well be the most commanding sound produced by a city bird in several hundred years? Does this fill him with joy? Or terror?

It has become fashionable to suppose that, in response to the plague, the world is going to retreat into various nationalisms, and border walls will never again shrink to their pre-plague modest proportions. But I am not sure. Just now I read that scientists in Brazil have made a potentially significant discovery—a discouraging discovery, as it happens—about a drug that is thought to hold out medical promise. Surely this is a sign that medical progress, when it comes about, will turn out to be an international achievement, and not a national one. Anyway, I notice my own experience. It was a friend in Italy who prepared me for the alarming screams of the ambulances at a time when, in my own New York, ambulances had not yet begun to scream. Just now a friend in Paris tells me that he is permitted to leave the house only for an hour to go for his jog, which makes me marvel at the looser welter of restrictions that impinge on my own existence. Isn’t that how everyone has been experiencing the event—internationally, that is? Each population around the world attends carefully to the other populations, hoping to glean a few tips. The South Koreans—how were they able to handle things so well? Every country on the planet gazes in admiration at South Korea. Isn’t the plague an internationalizing experience in this respect, shared by all?—though I do see that nationalists in one country after another have arrived at the opposite interpretation. Funny how the nationalists are all alike!

Years ago I used to report on guerrilla wars in Central America, which brought me to many a frightening place in the jungle; and my trips to the supermarket are a flashback experience. I gather together my protective gear, my mask and gloves and my fatalist resignation, and bleakly I plunge into the unknown. The supermarket has dispatched one of the Mexican clerks to stand guard at the door and control the crowd. But the clerk’s authority is not universally recognized. The line of people on the sidewalk is mostly a jumble. Someone rushes the door and the clerk orders him to the rear, which leads him to explode in wrath in my direction, which leads me to recoil in fear of his breath, which leads the people behind me to recoil. The clerk is furious. Inside, the aisles are thronged. The checkout line is a football scrimmage. “Next!” say the clerks, and the shoppers clump shoulder to shoulder, trying to get their credit cards to work. And here I am on the sidewalk again, grocery bags in hand, calculating how many faces have just now loomed within inches of my own, and how many surfaces have I fingered, and trying to figure out who is to blame—the store manager, I guess. Or the unruly shoppers. The president of the United States is to blame. I go home seething at that man, clutching my bags and trying not to crush the egg carton. Oh, God, I didn’t forget to buy something, did I?

Tocqueville believed that nature itself conspires on behalf of the human race, for the furtherance of God’s ultimate purpose, which is the rise of democracy everywhere on Earth—a view that he explained in the early thrilling pages of Democracy in America. The mountain ranges, the nearly empty Great Plains, the mighty rivers, the endless forests—all were meant to further the vast human project that was divine providence. But that was in the 19th century. Nature and man parted ways in subsequent centuries, and the divorce was ugly. In the 1980s, when I was reporting from Nicaragua, a civil war broke out between the left-wing Sandinistas and their campesino enemies, the Contras, and the fighting was monstrous. Neighbor killed neighbor. But the ecologists dismayed me further by pointing out that war among the humans was good for the nonhumans. Farming and its pesticides came to an end. The savannahs thrived, the jungles blossomed. And so it is with the pandemic of 2020. Mankind suffers. But the use of oil has diminished so profoundly as to have created a negative price for crude. And look at the air, as a result. The brilliance of the skies! Everyone sees it. The molecules shimmer. These are not the indications of nature conspiring on behalf of the human race. No, nature is gloating at our tragedy. We weep, nature laughs—a disconsoling truth.

How is love—sexy love—faring, in the time of the coronavirus? Everyone wants to know. John Gray, the philosopher, speculates that, in the age that is coming into being, online pornography will go into blossom, and internet dating will end up rendering virtual sex a normal thing, with augmented technology simulating “fleshly encounters.” The New York Times reports that something along those lines is already reality, at least in the form of online stripping. “Sex online, in general, seems through the roof.” So, OK. But that cannot be the real story. The real story can only be that lovers make their way to one another, in spite of everything. Maybe they sit in their separate seats for a few minutes. But then they say, “I don’t care—your experience will be mine, and mine yours, and our fates will be the same.” This is not to be encouraged. But what are they to do?

Suddenly I understand the old joke about anti-Semitism and the bicyclists. A guy says, “The First World War was caused by the bicyclists and the Jews.” Someone asks: “Why the bicyclists?” And a third guy responds: “Why the Jews?” The joke is funny because the first guy is plainly a screwball, but the second guy, who considers himself a rational thinker, is plainly an anti-Semite—as is made clear by the third guy. Hannah Arendt tells the joke in The Origins of Totalitarianism in order to reveal the irrationality of anti-Semitism. But only today do I understand the part about the bicyclists. I am lined up on the sidewalk along with everyone else in our face masks, awaiting admittance to the supermarket. Joggers come running by on the rest of the sidewalk, chests heaving, with no masks. The very first jogger annoys me, and, by the time a third one comes loping along, I have achieved emotional clarity. I hate joggers. They are oblivious to the breathy dangers they present to everyone else. They should be arrested, suppressed, and despised! And so, the joke about bicyclists takes on deeper meaning. Suddenly I understand that bicyclists might, in fact, be detestable. It is because anyone at all might be detestable. When you are under a fearful pressure, as are all of us in our face masks, to hate is natural, and any object at all will do, so long as some kind of feeble justification can be invented; and the feebler the justification, the easier it is to invent.

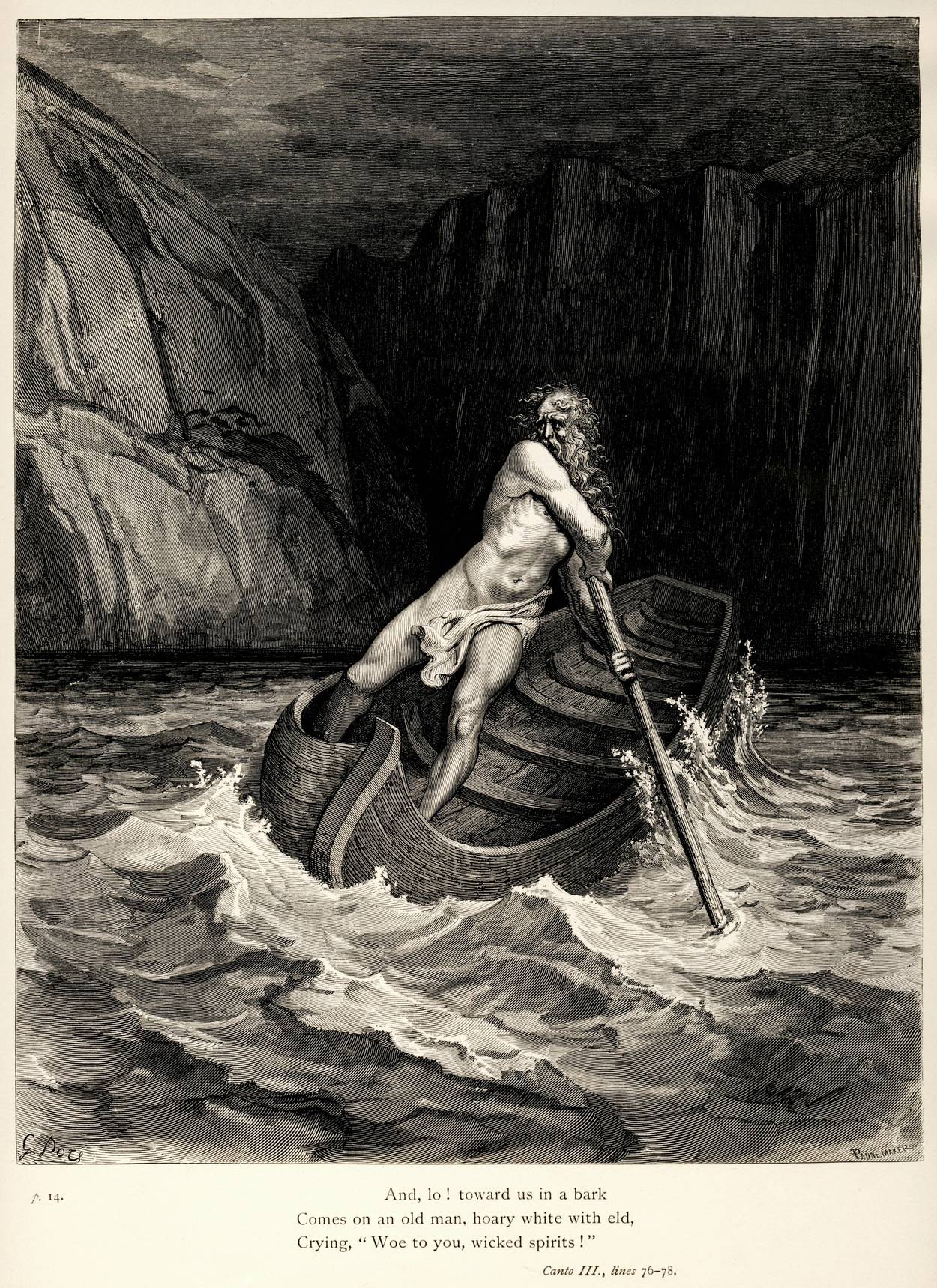

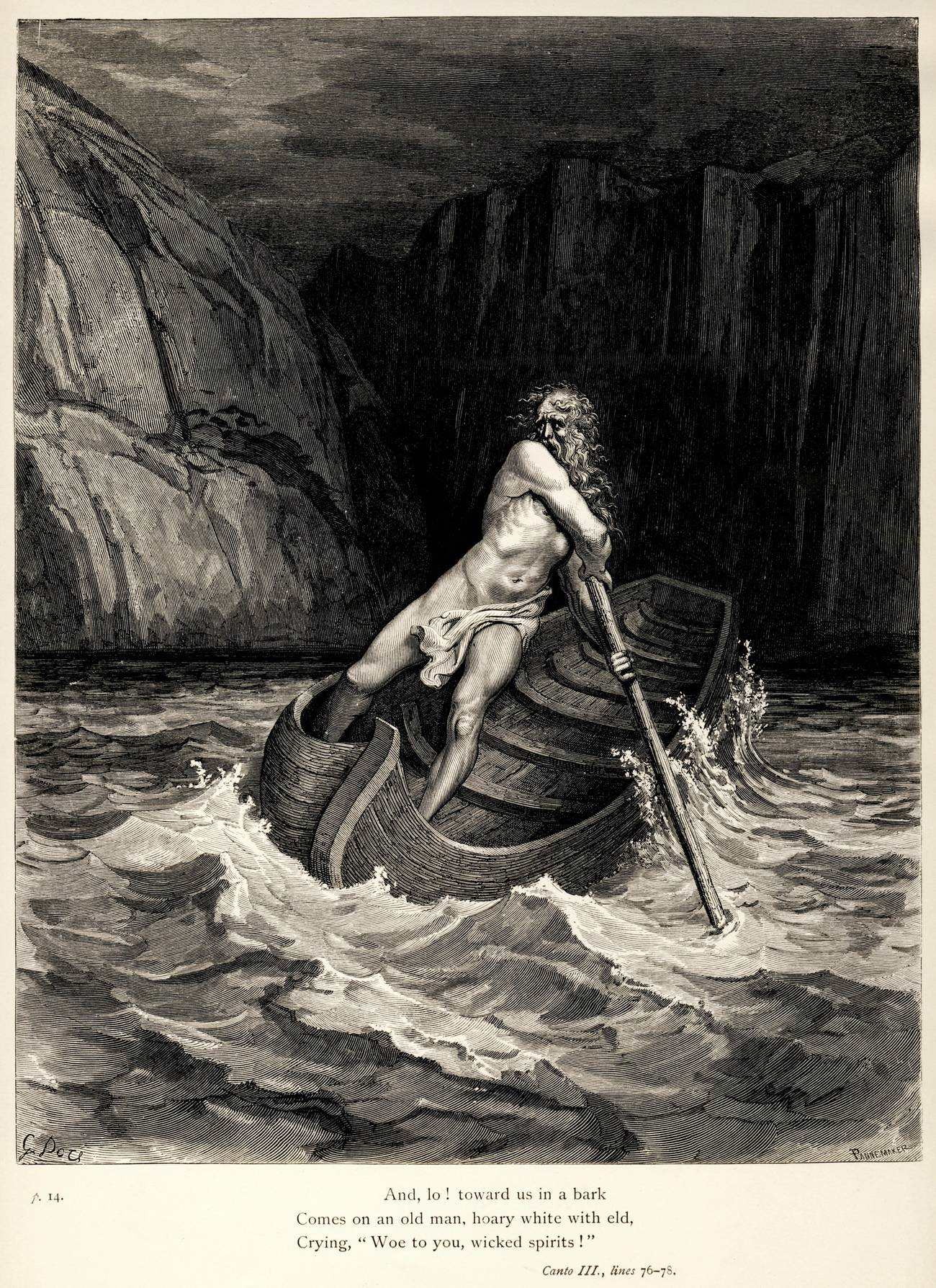

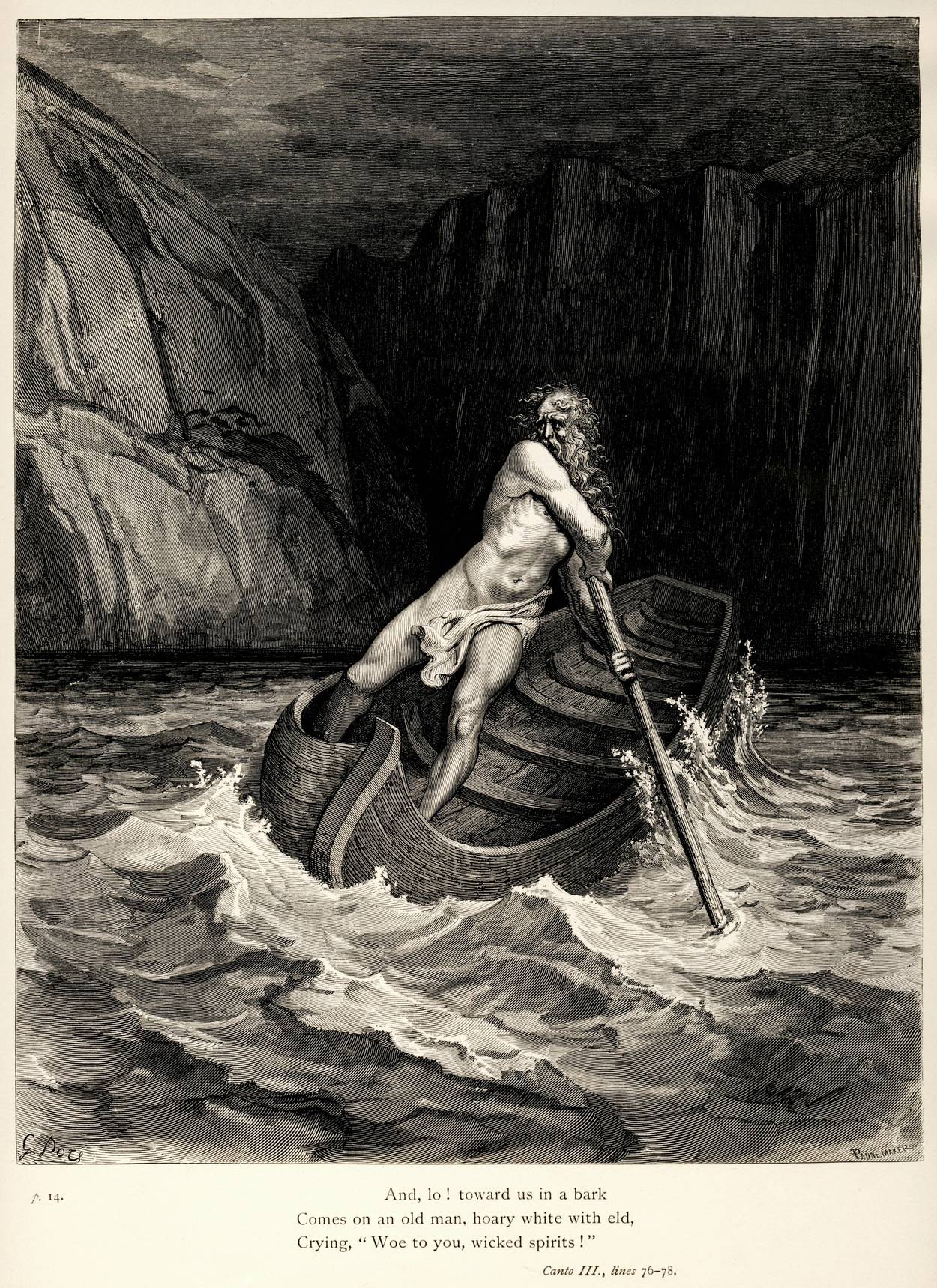

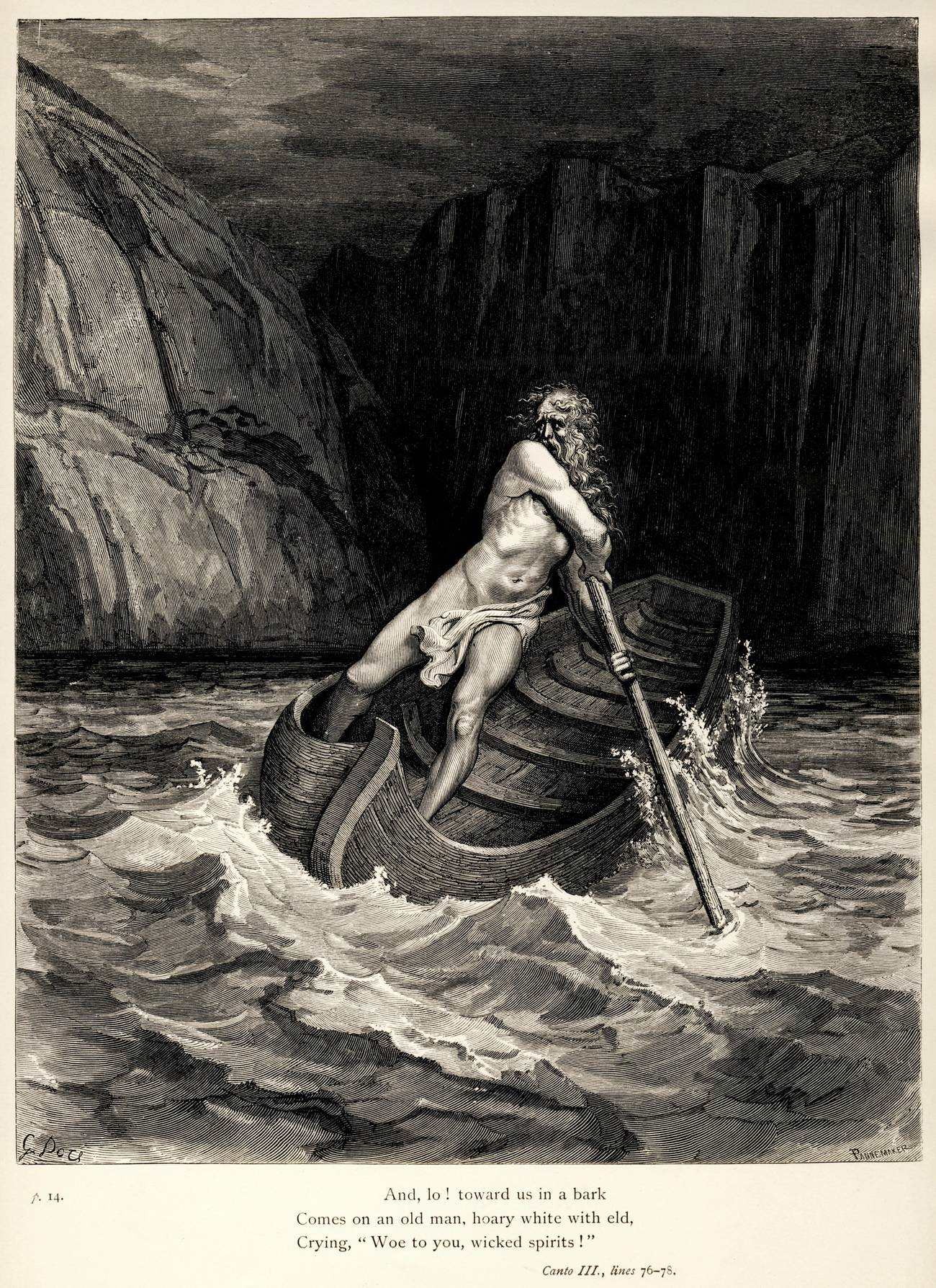

Brooklyn, spooky by day, is spookier by night. The avenue is a river, visibly motionless. A light passes, and then the shriek somewhere of the ambulance sirens. And the quiet returns—not a perfect silence, but the ghost of a rhythm, like the humid breath of a sleeping person, or the murmur of faraway waves, and then the shrieking again, and back to a liquid murmuring, and the slappy sound of the boatman’s oars in the water, as he rows into the underworld.

The rhythms make me recognize that I have had these experiences before, not in life, but in my readings. These are the rhythms of Virgil’s Aeneid, in the pages where Aeneas descends into the underworld to the ferryman: “This is the land of shadows, of Sleep and drowsy Night; living bodies I may not carry in the Stygian boat.” Or these are Virgil’s rhythms in the pages where Orpheus descends into the “black ooze and unsightly reeds” and the phantoms in the murk. Or these are the rhythms of the sobbing young woman in Paul Valéry’s World War I poem, “The Young Fate,” gliding on the funeral bark into the other world: “Spectres, sighs of the night in vain exhaled/go join the deaths of the impalpable numbers!” Stately rhythms, solemn, oozy, and dark—rhythms suspended between the one world and the other.

Paul Berman is Tablet’s critic-at-large. He is the author of A Tale of Two Utopias, Terror and Liberalism, Power and the Idealists, and The Flight of the Intellectuals.