Personal Revolution

Iranian, American, Jewish: Reflections on a complicated life

I am an Iranian-American Jew, an identity I have been proud of all of my life. I have been an American citizen since birth, and I have enjoyed the privileges of being part of the greatest, and freest country in the history of humankind. But my identity means that in addition to being intensely interested in what goes on in the United States, I am also intensely interested in what goes on in both Israel and Iran. All of these interests are part of who I am, as are the pain and the conflict that I experience because of my identity.

I have yet to visit Israel, but when I was young, my family made a number of trips to Iran even after immigrating to the United States. Those visits occurred before the Islamic revolution, when Iranian Jews were reasonably free and reasonably prosperous. Everyone in my family assumed that we would be able to visit Iran as we pleased.

But 1976 was the last time I visited Iran. After the Islamic revolution of 1979, the country of my mother and father became closed to them and to much of the rest of my family.

Plenty of Iranians abroad have made trips to and from Iran ever since the revolution, of course. But as Iranian Jews, we have had to endure a greater sense of insecurity and a relationship with the Islamic regime that has been fraught with tension. That tension has only increased in recent years, with the regime having become increasingly hardline, and with Muslim Iranian-Americans like Roxana Saberi, Haleh Esfandiari, Ali Shakeri, Kian Tajbakhsh, and Parnaz Azima having been imprisoned on trips to Iran, despite the fact that they did nothing to merit their sentences.

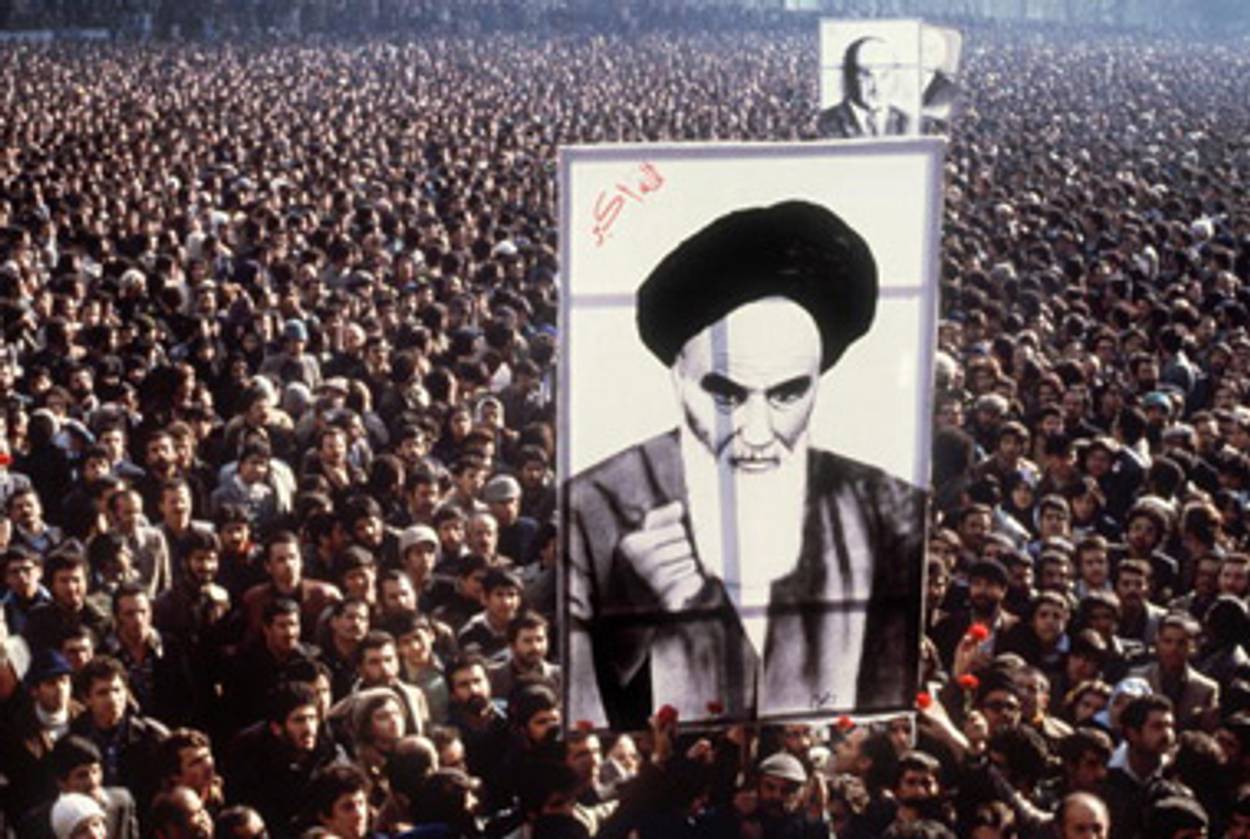

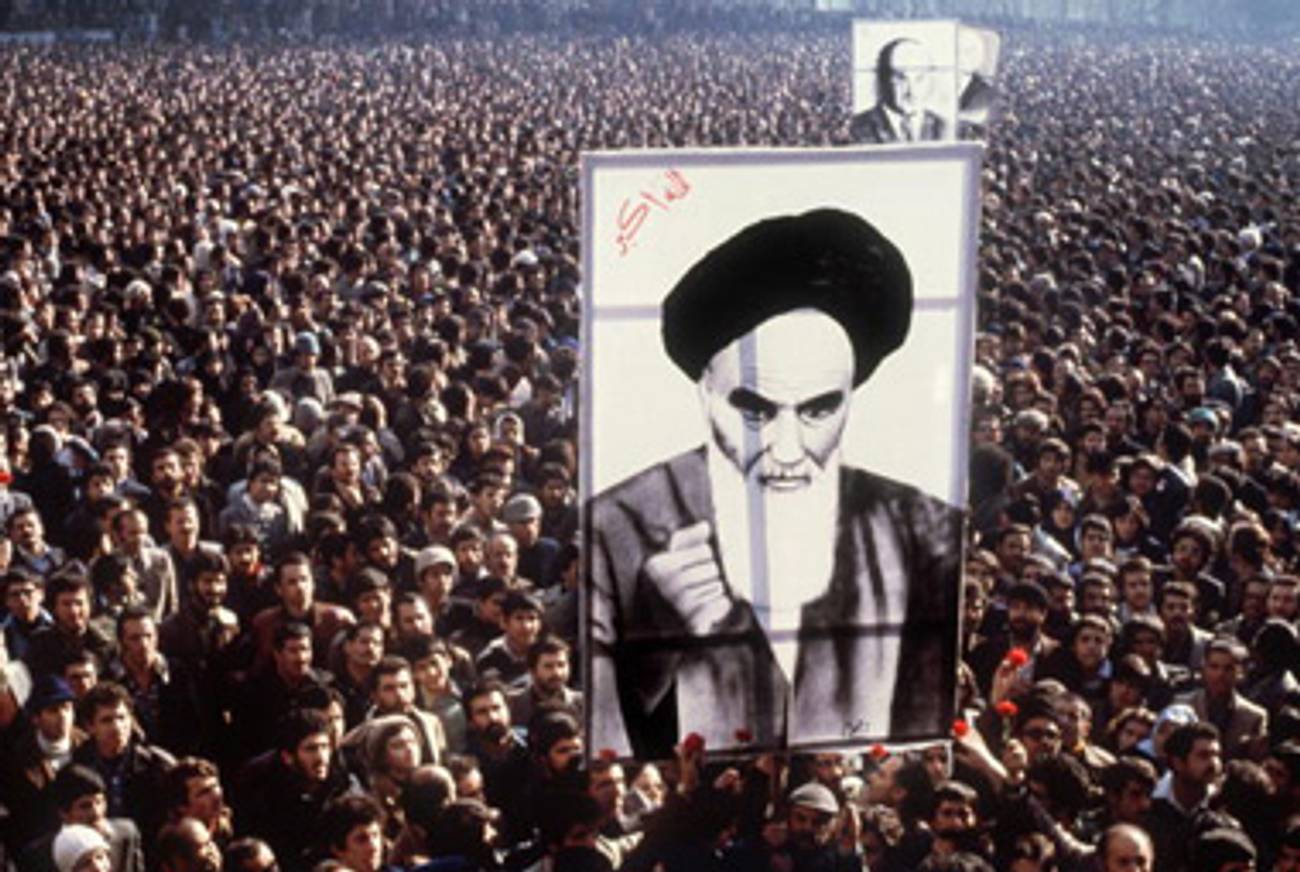

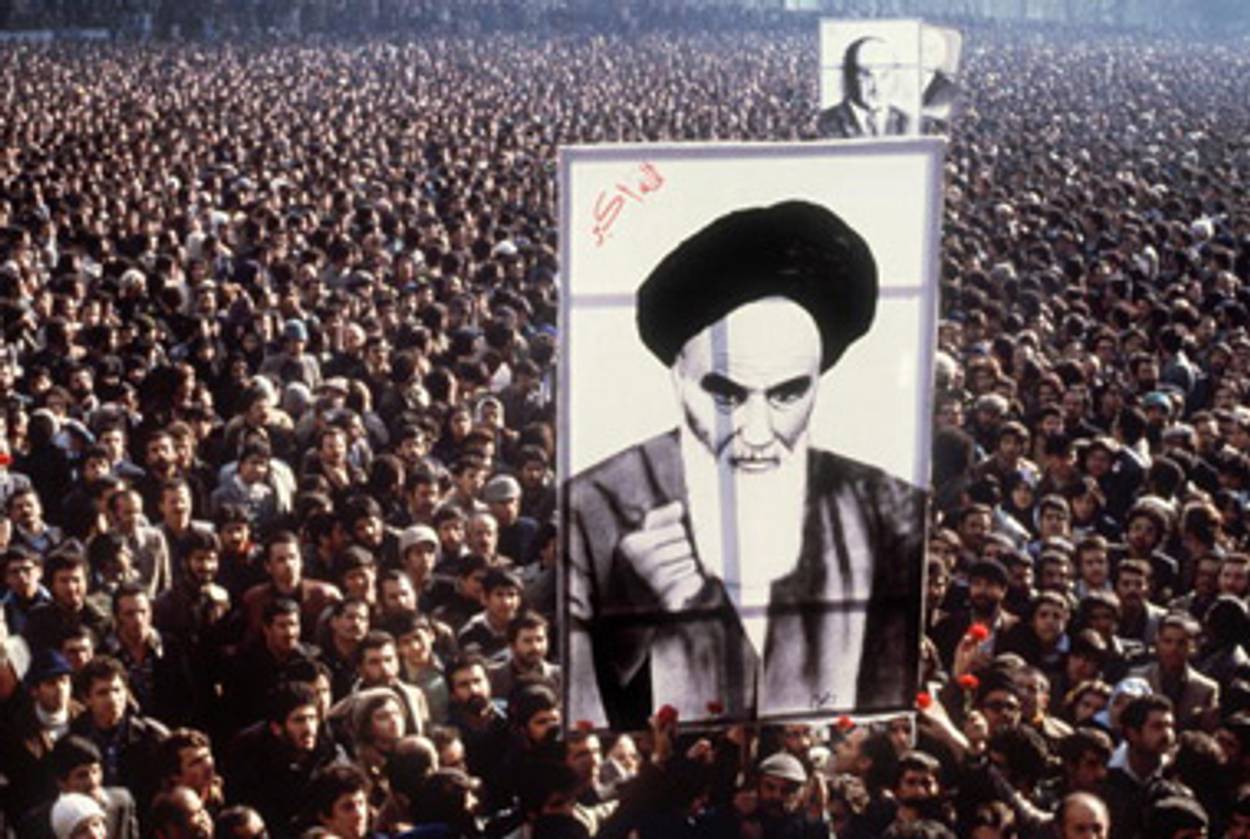

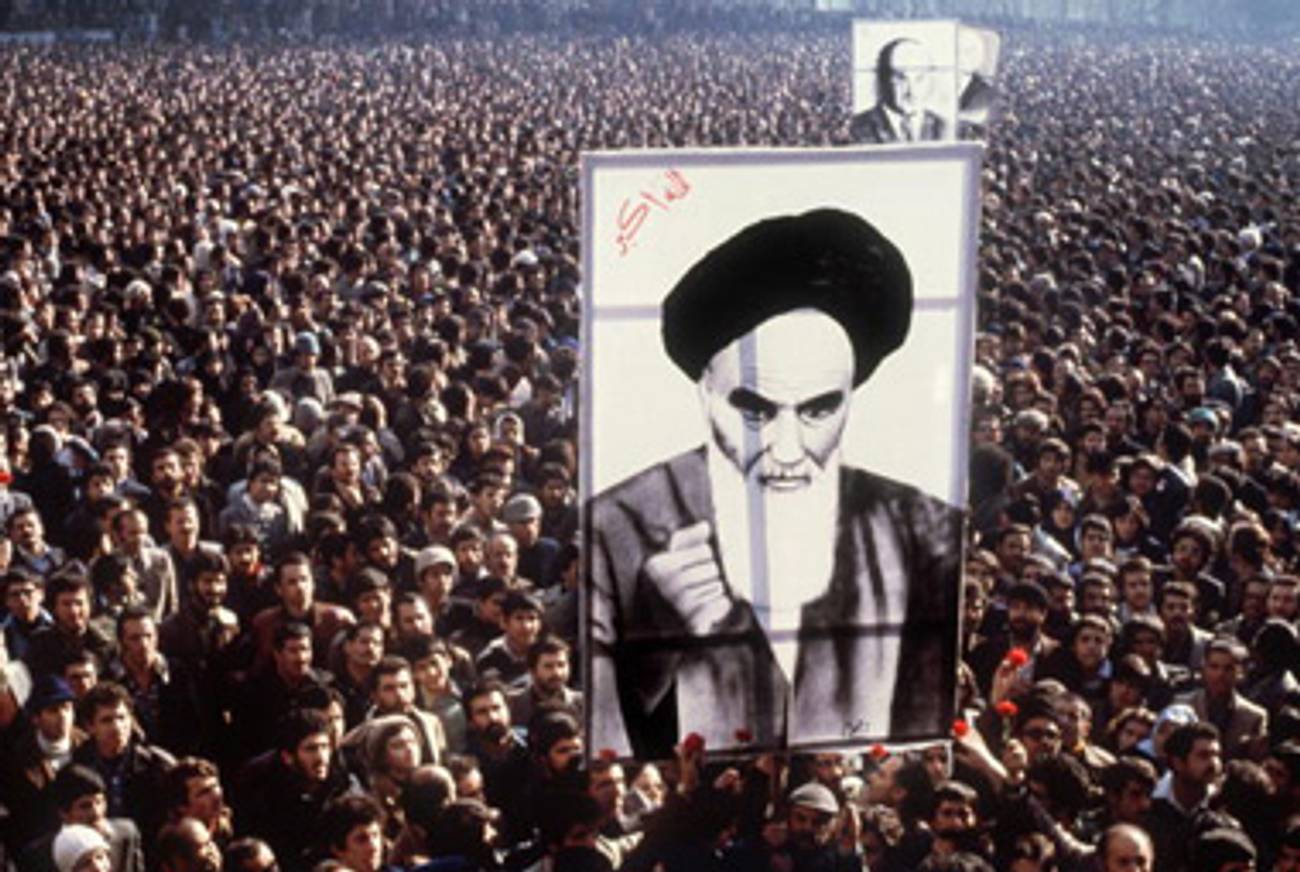

I watched the Iranian revolution unfold on American television. I saw the images of the demonstrations in the streets and the unforgiving mien of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini as he declared that the monarchy must come to an end and a theocracy must take its place. From the very beginnings of the revolution, it was made clear to me that our family could not possibly visit Iran until a fundamental governmental change took place. In a phone call as a child, I once told my grandmother, who’d remained in Iran, that I probably would not be able to see her until there was a counterrevolution; an indiscretion that prompted my parents to quickly take the phone out of my hands, for fear the line was eavesdropped and I might get my family in trouble.

The images from Iran made me intensely political in 1978, at the tender age of 6. My family and I believed that something was happening in Iran that would be profoundly destructive to the country. Because of our religious identity, our concerns were heightened by the theocratic aspect of the revolution. Sadly, those concerns turned out to be justified; while Iran’s Jewish population has some rights, the Jews of Iran are forced to denounce Israel with great frequency and fervor.

Being an Iranian Jew is a great source of pride, but it is also a great burden. It meant a difficult life for family members who tried to leave Iran in the early 1980s, only to be caught, imprisoned, whipped, and threatened with execution unless they signed a statement acknowledging their “guilt” in relation to vague and nonsensical allegations. It meant a difficult life for a relative who did not want to go to the front to kill Iraqis—or be killed by them—and who was threatened with expulsion from the University of Tehran unless he dropped his resistance to being drafted for war. It meant difficulties for another family member, who went back to Iran to see my grandmother (for what turned out to be the last time) and was prevented from returning to the West for two weeks while various corrupt officials demanded bribes and threatened to take my grandmother’s home—where I remember playing as a child—away from her.

I try to be patient, waiting for change to come to Iran. But even as the regime gives observers every reason to be outraged at its actions, global indifference seems to outweigh any sense of justified indignation regarding the actions of the regime. I am impatient with an American society that would rather focus on Bristol Palin’s appearance on Dancing With the Stars than on Iran. I am impatient with the current U.S. administration, which has done little to speak up for the proposition that people should not be beaten up, that their votes should not be stolen, and that their political and human rights ought to be respected, for fear of appearing to be imperialist.

Of course, protesters in Iran are not likely to castigate the Obama Administration as imperialist in the event that the administration ever chooses to forcefully argue on behalf of human rights and political liberalization in Iran; indeed, if anything, the Iranian people have made clear that they want more American assistance in their effort to bring about political change. But for whatever reason, the Obama Administration chooses not to side with the Iranian people against their repressive leaders. From a realpolitik perspective, I am frustrated with the lack of pressure that has been put on Iran thus far, pressure that might have created divisions within the regime that might help the United States achieve crucial national security interests. (And, no, an ineffective sanctions regime does not count as “pressure on Iran.”)

It is obvious that a renewal in protests will result in more injuries and deaths to the many who brave the streets to demonstrate for things we in the West take for granted; free elections, free speech, basic political and human rights. The prospect of further bloodshed horrifies me. It certainly horrifies those living in Iran whose lives and well-being may be threatened by another flare-up of political violence. But ever since the revolution ousted one dictator—the shah—and put another far worse in his place, the need for political liberalization has become overwhelming and undeniable. Iran has had its chances for political liberalization, only to have seen them slip away. On June 29, 1981, an assassin just missed killing the father of the Islamic revolution, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, with a bomb (the bomb blast ended up severely injuring the current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, whose right arm is useless and withered as a result of the assassination attempt). I remember being angry and infuriated that a rare chance to kill Khomeini—and perhaps (at least to my 9-year-old mind) reverse the effects of the revolution—was missed. I thought that perhaps the regime would be toppled when the student revolts of 1999 began, only to watch in despair as the uprising was brutally put down by the thugs the regime employs to keep order. How many more missed chances can the country’s body politic afford?

And, finally, there is Iran’s conflict with Israel. It’s an issue that torments Iranian Jews, who care deeply about what happens to Iran but are not willing to see the Islamic regime harm Israel’s security interests or the lives of innocent Israelis—many of whom are émigrés from Iran. Were it a conflict with any other country antagonistic toward Israel, Iranian Jews would have significantly less hesitation—if any—in endorsing a military response to any threat to Israel. But in this case, the country antagonistic toward Israel is Iran, to which Iranian Jews naturally and obviously continue to feel a deep tie. As such, Iranian Jews are faced with a revolting choice: endorse military strikes against Iran that may—or may not—set back the nuclear program but may also kill scores of Iranians, or do nothing and gamble that Israel will not be consumed by a nuclear conflagration.

Thus the life of an Iranian-American Jew. It entails conflicted emotions, constant apprehension, intense frustration, the fear of being forgotten and ignored, and a sense of exile, a longing for what so many take for granted—the ability to visit home. The Iranian Jew is heir to a glorious legacy; our ancestors helped author the Babylonian Talmud. The Iranian Jew looks to an uncertain future; we do not know how long our exile will last, whether it will end in our lifetimes, or whether the various and distinct parts of our lives will ever stop being in conflict with one another. We only know how to persevere. We have had thousands of years of practice at persevering, and we do what we can to effect positive change where we are able, in the hopes that we will be able to build a life for ourselves that does not entail the sense of sorrow, fear, and disconnectedness that we have felt for so long.