Are Politicians Who Talk About God Crazy?

The American personal relationship with God is weird and off-putting to Israelis, as I found out to my dismay. But the poles of religiosity may be reversing.

The note placed on the lectern in the middle of my remarks read, “Peres dead. Return immediately.” I instantly stopped and apologized to the audience for having to leave. The president of Israel had passed away and, as deputy minister in charge of diplomacy, I had to rush back to Israel and help host the many foreign dignitaries expected to arrive.

Speeding to the airport, though, I experienced a pang of guilt. I was in the United States to deliver High Holiday sermons to Reform and Conservative synagogues, but now I would let them down. Less altruistically, perhaps, I believed my message would be welcomed by their congregations. I’d already given the remarks at a modern Orthodox shul in New York and received—on Shabbat—a standing ovation. Glancing at my watch and hoping I had enough time, I told the driver to turn off the highway to the airport and head for the Israeli Consulate. There, after hastily setting up a camera, I recorded my 17-minute speech and sent it to the rabbis I’d stood up.

Shimon Peres’ funeral nearly rivaled Nelson Mandela’s, with delegations from 70 countries attending. Presidents Barack Obama and Bill Clinton spoke, as did Israeli author Amoz Oz and Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. Even Prince Charles paid his respects. Many world leaders remained for talks with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. I scarcely slept for the next two days participating in back-to-back discussions with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, British Foreign Minister Boris Johnson, and Francois Hollande, the president of France. The last thing I expected, when the last of the dignitaries departed, was to be made a national laughingstock.

Someone had posted my video which, even at 17 minutes, went viral in Israel. Some 40,000 viewers watched it in the first day. Suddenly, every news outlet was desperate to interview me or, more accurately, to ridicule me for what I had told my American audiences. Embarrassingly enough, I’d spoken of challenges I’d experienced earlier in life but, more outrageously, I’d revealed my faith in God.

The speech opened by mentioning the dyslexia I’d suffered as child, my weight problems, bad school grades, and hopelessness at athletics. “I was weird.” Often alone, I wandered through the nearby woods and there had conversations with God. “I didn’t ask to be thin or smart or play third base for the Yankees—well, maybe once—but instead merely asked, ‘what do you want from me?’” I asked to be able to serve, to be given the wisdom and love to be a better, kinder person. “Help me to be more like You.”

The approach was exactly the opposite of the one I’d recently encountered in houses of worship across the United States. There, the members would insist, “in my synagogue, God detests gay marriage,” or, conversely, “in my church, God celebrates gay marriage.” God either supported or abhorred Israeli settlements in Judea and Samaria, preferred universalism over tribalism, upheld or criminalized abortion—according to the congregants. The practice, I suggested, was worse than the ancient pagans’, in which the gods resembled humans. Now, God looked like only one human—you—and conformed with your beliefs. “This is the religion in which the God you worship is essentially yourself,” I posited. “This is neo-paganism.”

And nothing could be more un-Jewish. In the Bible, God tells Abraham that he cannot be like everyone else, he cannot pray to idols or sacrifice his firstborn, but must separate himself and strive for a higher morality. He must be a Hebrew—an ivri, one who crosses over into both a promised land and a life of divinely determined service. God’s demand for selflessness sounds steep today, and certainly was even in Abraham’s time. Still, heneini, he unhesitatingly responded. “I’m here.”

Neo-paganism, I went on to warn, threatened not only organized religion but civilization as a whole, fracturing its formerly universal beliefs and dissolving the unity necessary for defending them. Israel, I concluded, had a crucial role in “reconnecting to the idea that human beings are created in God’s image, and not vice-versa, to serve God’s and not our agenda.”

The thesis was provocative, admittedly, but it was not what got me lampooned. Rather, it was the ludicrousness of an Israeli politician openly admitting his handicaps. Unlike Obama, who often joked about what it was like growing up with big ears and a funny name, Netanyahu never once mentioned the childhood accident that scarred his upper lip. Nor would Foreign Minister Yair Lapid make light of being short. Campaign posters show Israeli candidates growling, not smiling as in America, and from their portraits on state office walls, Israeli prime ministers snarl. Unlike the American leaders who can afford to appear human, the heads of the ever-endangered Jewish state must never show the slightest weakness.

Unlike the American leaders who can afford to appear human, the heads of the ever-endangered Jewish state must never show the slightest weakness.

But beyond my confession of dyslexia, Israelis derided my faith. “A cross between a confessional therapy session, a minister’s sermon, and a pro-Israel university lecture,” Ha’aretz called my speech. Social media was even less complimentary, denouncing it in Hebrew as “embarrassing,” “surreal,” “cuckoo,” “freakish,” and even “deranged.” One anomalous critic noted that, in the bigotry I’d shown to the billions of people not of the Abrahamic faith, I appeared to be addressing not Jews on our New Year but evangelical Christians on The 700 Club.

In response, I tried to explain that one cannot talk to Americans, Christians, Jews, or Muslims without recalling personal challenges and how they were overcome. You cannot give Americans an Israeli speech about war, guts, and cherry tomatoes and expect to reach them. And addressing congregations, especially on Rosh Hashanah, you must talk about God. You must affirm not only your belief in the God of Israel but attest to some personal rapport.

None of these explanations sufficed, however. Even Orthodox Israelis seemed to recoil from my message. Catching me in the hall outside the prime minister’s office, Netanyahu’s military secretary, a religiously observant general, whispered, “I like what you said but, truth be told, TMI.”

Unwittingly, clearly, I’d crossed a line, and not only by admitting my faults. Religion in America plays a fundamentally different role—institutionally and publicly—than it does in Israel. While rigorously separating church from state, the Founding Fathers assigned them different responsibilities. Government was in charge of the civic sphere, but religion managed the moral. The two, moreover, were co-dependent. “Reason and experience both forbid us to expect that national morality can prevail in exclusion of religious principle,” George Washington declared, emphasizing that free government rested on religion. Alexis de Tocqueville went further by viewing religion as a necessary check on democracy’s dangers—the tyranny of the majority, materialism, hyperindividualism—and should be considered “the first of America’s political institutions.”

God, in fact, permeates America. The name appears on the currency, in the Pledge of Allegiance, and (as the Creator) in the Declaration of Independence. Testifiers in American courts swear, “so help me God,” as do judges, soldiers, and presidents. Politicians, especially, even the most secular among them, must repeatedly proclaim their faith. Dwight D. Eisenhower, in his first inaugural address, mentioned it no less than 14 times; “God” was cited five times even in Donald Trump’s. A president whom no one mistook for God-fearing nevertheless saw value in posing outside a Washington church holding a Bible. The same Barack Obama who once railed against those who “cling to guns and religion” defined himself at times as a born-again Christian. Each year of my ambassadorship, I watched him talk fervently about his faith to the thousands of attendees of the National Prayer Breakfast, and call the others on the dais—Republicans and Democrats alike—“my brothers in Christ.”

None of this exists in Israel. There is no equivalent in Hatikvah to God Bless America, and in our Declaration of Independence, only a vague reference to the “Rock of Israel.” Secular politicians do not speak about their spirituality, but neither do their ultra-Orthodox counterparts. Commandments, yes; the Almighty, no. Our current kippa-wearing prime minister has been photographed in tallit and tefillin but never once quoted on his beliefs. A country that hardly separates synagogue from state effectively excises God and faith from its public discourse.

Why? How is it that two nations with deep roots in the biblical traditions could harbor such different approaches to God and faith? And why must professions about them be lauded in one society but lambasted in another?

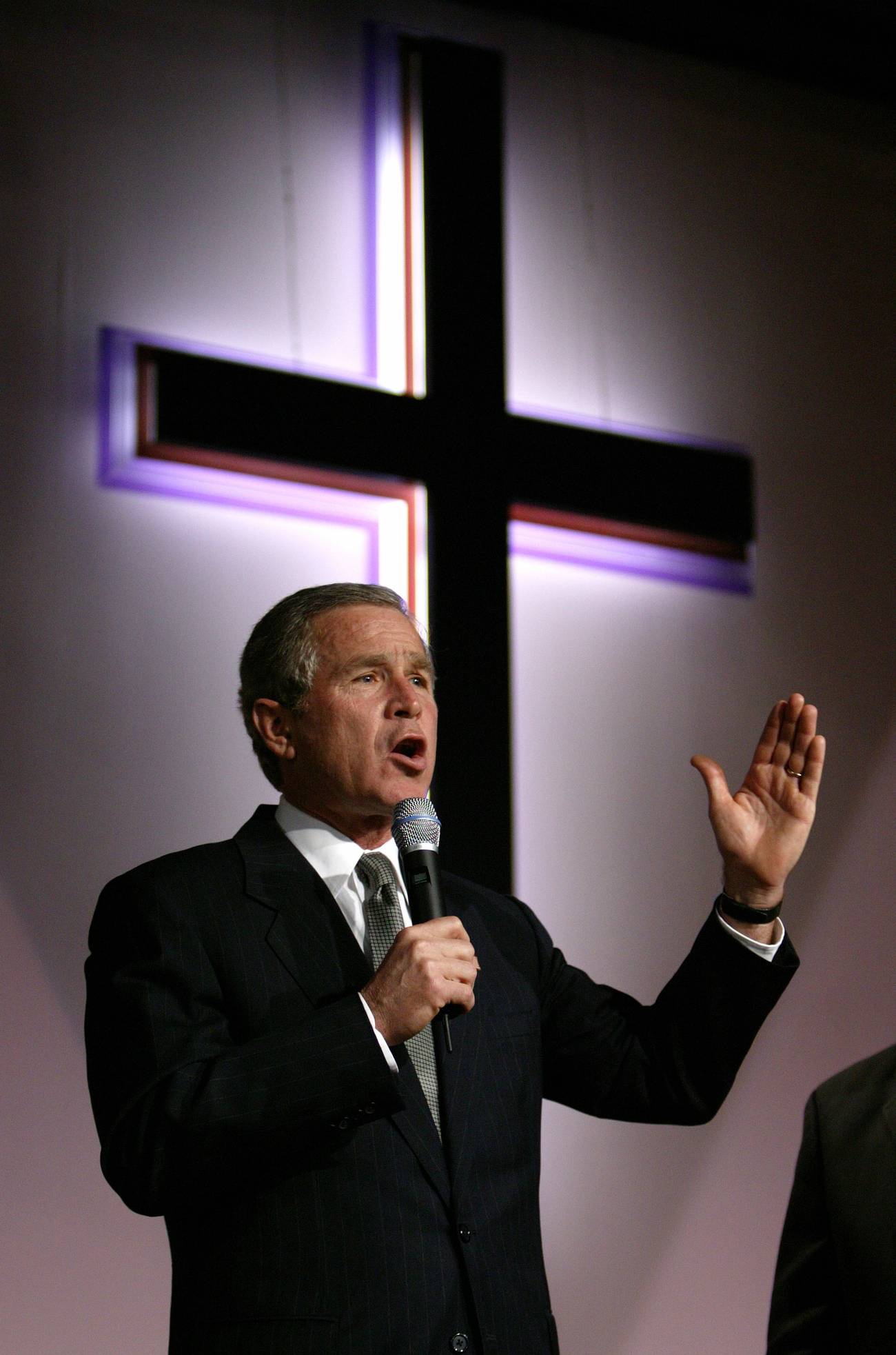

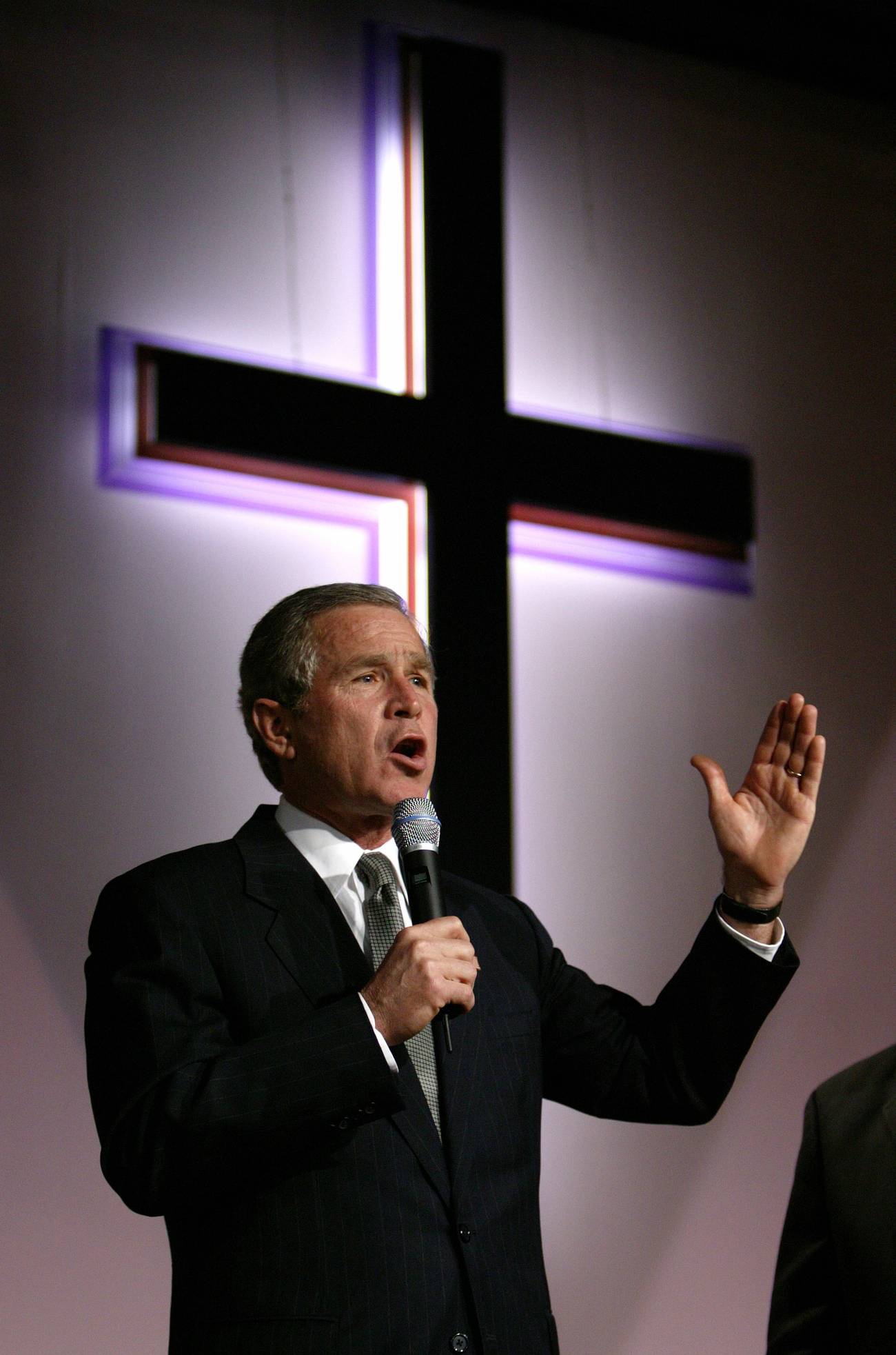

The God of America speaks to presidents like George W. Bush, but the God of Israel has not spoken to Jewish leaders since biblical times.

The simple answer is that America’s God is a Christian God, a personal, loving God with whom millions of citizens are on a first-name basis. Israel’s God, by contrast, is both collective and morally judgmental—the God of “Our father, our king,” and “We transgressed. We sinned.” His real name is unpronounceable and hidden by such euphemisms as “Hashem” and “haKadosh baruch hu.” The God of America speaks to presidents like George W. Bush, but the God of Israel has not spoken to Jewish leaders since biblical times. Prophecy, the Talmud tells us, in the post-prophetic age, is reserved for fools and children. Those who claimed otherwise, from Jacob Frank to Sabbatai Zevi, wrought trauma. No wonder that Israelis would call any countryman who spoke with God a madman.

Originally, at least, the United States and Israel were similarly viewed as Promised Lands, justified by divine promises and Manifest Destiny. But while the Founders believed in God as well as in His pledges, most of the Zionist pioneers accepted the pledges but rejected the God. Unlike the American revolution, which fought for freedom of religion, the Zionists’ was a European revolution of freedom from religion. Public professions of faith would, in the Israeli public sphere, seem reactionary. Not surprisingly, the lyrics to the Exodus song, “This land is mine, God gave this land to me,” that we all sang in our American Jewish youth movements growing up, were penned by Pat Boone, an evangelical Christian.

So perhaps the responses to my neo-paganism speech were somewhat predictable—standing ovations in the United States, scorn in Israel. And yet, the situation may be changing. Given the sharp decline in church attendance in the United States, future American leaders might be expected to put less emphasis on their religious beliefs. Israel is heading in exactly the opposite direction, with new and vibrant synagogues opening frequently, even in historically godless Tel Aviv. Beginning with Meir Ariel, Kobi Oz, Meir Banai, and Shotei Hanevuah (“The Fools of Prophecy”), Israeli rock music has been infused with passionate Judaism. “I do not owe anything to anyone,” Religious Affairs Minister Matan Kahana, defending his kashrut reform from ultra-Orthodox attacks, recently declared. “Only to God.”

But my video remains indelibly ensconced on the internet as “The Madness of Michael Oren.” Still, once in a while, a young person, usually religious, will approach me on the street and thank me for my courage. And a year after my public pillorying, I led a multipartisan Knesset delegation to the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington. The MKs sat open-mouthed as a procession of senior American officials rose to testify how the Lord had lifted them up from failure and saved their families, careers, and souls. Later, my colleagues rushed to embrace me. “Now we understand,” they assured me. “And we thought you were merely insane.”

Michael Oren, formerly Israel’s Ambassador to the United States, a Member of the Knesset, and Deputy Minister in the Prime Minister’s Office, is the author of To All Who Call in Truth (Wicked Son, 2021).