Questioning Bobby Fischer

ESPN’s Jeremy Schaap reported many difficult stories throughout his career, but it’s his interview with the troubled and anti-Semitic chess great he’ll never forget

There is no place on earth more (less?) ideal than Jerusalem for pondering the mysteries of existence, and for a not-insignificant number of people mysteries don’t get more engrossing than the self-exile of chess prodigy Bobby Fischer. The all-time great retreated into obscurity—and, later, derangement—at the age of 32, shortly after refusing to defend his 1972 world championship, which he captured against Soviet grandmaster Boris Spassky. Fischer played tantalizingly little high-level chess after 1972, joined a cult for a time, and then became a full-blown anti-American and anti-Semitic conspiracy theorist. Having died in 2008, he is no longer alive to explain himself, but dwelling on the irrevocable and insoluble past is of course part of the reason to come to Jerusalem in the first place.

The upscale flesich restaurant where veteran ESPN correspondent Jeremy Schaap and I sat was in a shopping mall nestled within a stone mirage of condos peched far beyond eyeshot of the holy city’s ancient centers of mystery-contemplation, thank God. But no amount of garishness can fully hide that you’re in Jerusalem, and there’s probably no other place on earth where Schaap and I would have had any reason to cross paths. The very fact of meeting Schaap was slightly surreal, since I can’t remember a time in my life when he hasn’t been there in some form of another—When I saw Schaap was moderating a panel at the Sixth Global Forum to Combat Anti-Semitism, which I planned on covering, I mentioned in an email to ESPN’s press office that I had listened to the Sunday morning radio show that he’d co-hosted with his late father Dick Schaap on the way to Hebrew school when I was a kid. In the almost two decades since then, Schaap has become the reporter that ESPN entrusts with the hardest stories in sports, a subsection of life that reflects all the ugliness of the broader world: He’s reported on child prizefighting in Thailand, worker abuse at Qatar’s World Cup construction sites, and racism among the fans of Beitar Jerusalem.

I was most eager to talk to Schaap about Fischer. Luckily Schaap raised the chess player before the schnitzel had even arrived, mentioning Fischer as one possibility when asked him to name the most memorable story he’d produced. Schaap says he’s interviewed Mike Tyson roughly 100 times—Tyson’s immortal premonition that he would “fade into Bolivian” shortly after getting throttled by Lennox Lewis came in response to one of Schaap’s post-fight questions. Even off-camera, Schaap subtly switches between an almost-boyish enthusiasm and newsman-type sobriety; it makes sense that someone of his discernment figured how to get an enigma like Tyson to feel comfortable. He’s cracked harder puzzles than Tyson, too: Schaap’s 2005 report on Fischer is still perhaps the most enduring moment of the reporter’s decorated career, as well as one of the climactic events in Fischer’s uniquely strange American Jewish saga.

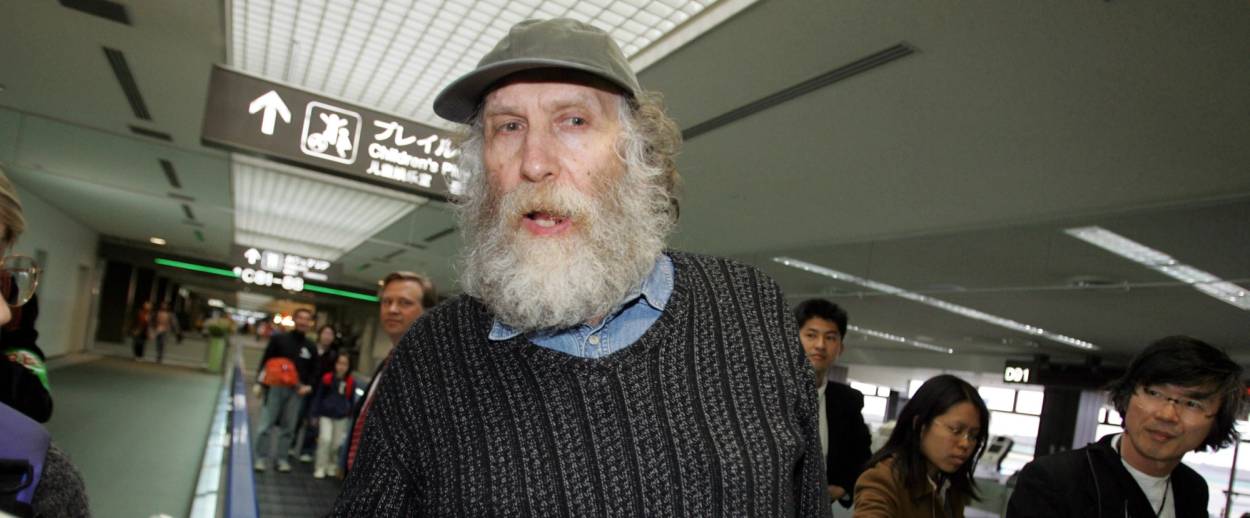

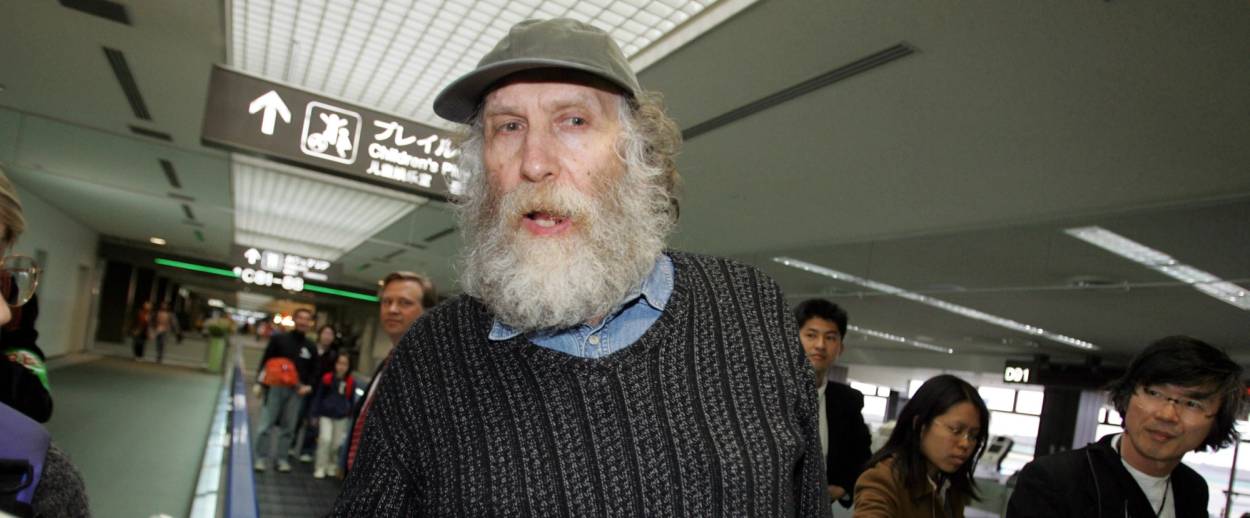

In 2004, Fischer was arrested in Japan while attempting to fly to the Philippines—the chess legend had been a fugitive from US law for violating American sanctions against Yugoslavia when he played a re-match with Spassky in present-day Montenegro in 1992. After eight months in detention in Japan, Iceland gave Fischer citizenship and Schaap, whose father became close with Fischer when he was a child chess phenom, was at the Reykjavik airport waiting for him.

“For thirty years people were trying to get him to say something on the record and that was the whole point of going there: Maybe we get an interview with Bobby Fischer, the guy who’s never explained himself.” At the airport, Fischer appeared to brush off Schaap, who tried to approach the mercurial former champion during a tarmac press-scrum. In fact, Fischer knew who Schaap was, and was still nursing a sense of hurt and betrayal related to more or less accurate comments that Dick Schaap penned about Fischer in a 1979 article. “I genuinely like Bobby Fischer,” wrote the elder Schaap, a leading sports journalist and widely beloved ESPN fixture who died in 2001. “He possesses two classic virtues: He is never dull, and he does not have a sane bone in his body. I’ll let you know when I find him. Don’t hold your breath.”

“I had no intention of making it about me,” Schaap told me of his now 13-year-old story on Fischer. But Schaap acknowledged, “the most profound stuff we do ends up being about us—or somehow it’s felt personally instead of professionally.”

The morning after his arrival in Reykjavik in 2005, Fischer called a surprise press conference where Schaap seemed to be the only journalist interested in pressing him on the big, obvious questions: Why he’d broken US law to play Spassky, and why he’d all but disappeared for over three decades. Fischer, hidden under a baseball cap and speaking in a disarmingly thick Brooklyn accent, didn’t provide anything resembling a satisfactory answer—but he did reveal something about his own state of mind. “I hate to rap people personally but his father many, many years ago befriended me, took me out to see…Knicks games. Acted like a father figure. And then later like a typical Jewish snake, he had the most viscous things to say about me. Did you read what he said about me in that article?,” Fischer barked at Schaap. “Did you read the article where he said that there’s not a sane bone in my body?”

Schaap, summoning almost superhuman powers of dispassion, replied: “I know he said it…and honestly I don’t know that you’ve done much here today to disprove anything he said.” The ensuing stare-down between Schaap and Fischer is still electrifying over a decade later: It’s as if every question about Fischer is somehow answered and then un-answered and then exploded to pieces within three seconds of glacial silence.

“There’s this weird kind of circularity to the story,” Schaap said in Jerusalem, “because we’re showing you how crazy he is and then we’re having a fight about how crazy he is because he objects to my father having called him crazy, which is crazy. And then—this is making sense?” I assured him it was. “My father said it not to attack him, but to explain him to people. You know? When he said he didn’t have a sane bone in his body, he wasn’t saying, forget about Bobby, dismiss him, he’s saying, take some pity on him, he doesn’t have a sane bone on his body. Or you know, forgive him.”

Today, what’s unforgivable about Bobby Fischer isn’t so much his anti-Semitism, which now looks like one of several symptoms of a diseased mind and is notable primarily as a reminder that the Jews are what such minds often turn to sooner or later. What’s harder to grasp is the impossibility of any real answers. What disease—if it was a disease—fueled Fischer’s hatred and sent him running from the world? What was one of the most singular intellects in existence denying us and himself through 30 years of self-exile? And again, why? Schaap’s showdown with Fischer is still powerful because it’s one of modern journalism’s most compelling moments of anti-closure, resonating because it draws attention to what we’ll never get to learn.

“It’s really sad,” Schaap said of his faceoff with Fischer. “And it’s sad in a way that we’re not used to being sad about things.” Fischer’s wasn’t the familiar tale of a competitor struggling against tragic circumstances. “This was a sad story about someone who could have been one thing and ended up being something else.” From a reporting perspective, it was a cosmic collision of the personal, professional, and even the existential—entire journalistic careers contain less meaning than those few seconds of silent confrontation in Reykjavik, which would have been impossible for even the most clever broadcaster to engineer. One important possible upshot, even for a reporter with Schaap’s breadth of experience, is that you shouldn’t expect to get two of those. “I’ll never have another moment like that, you know?”

Armin Rosen is a staff writer for Tablet Magazine.