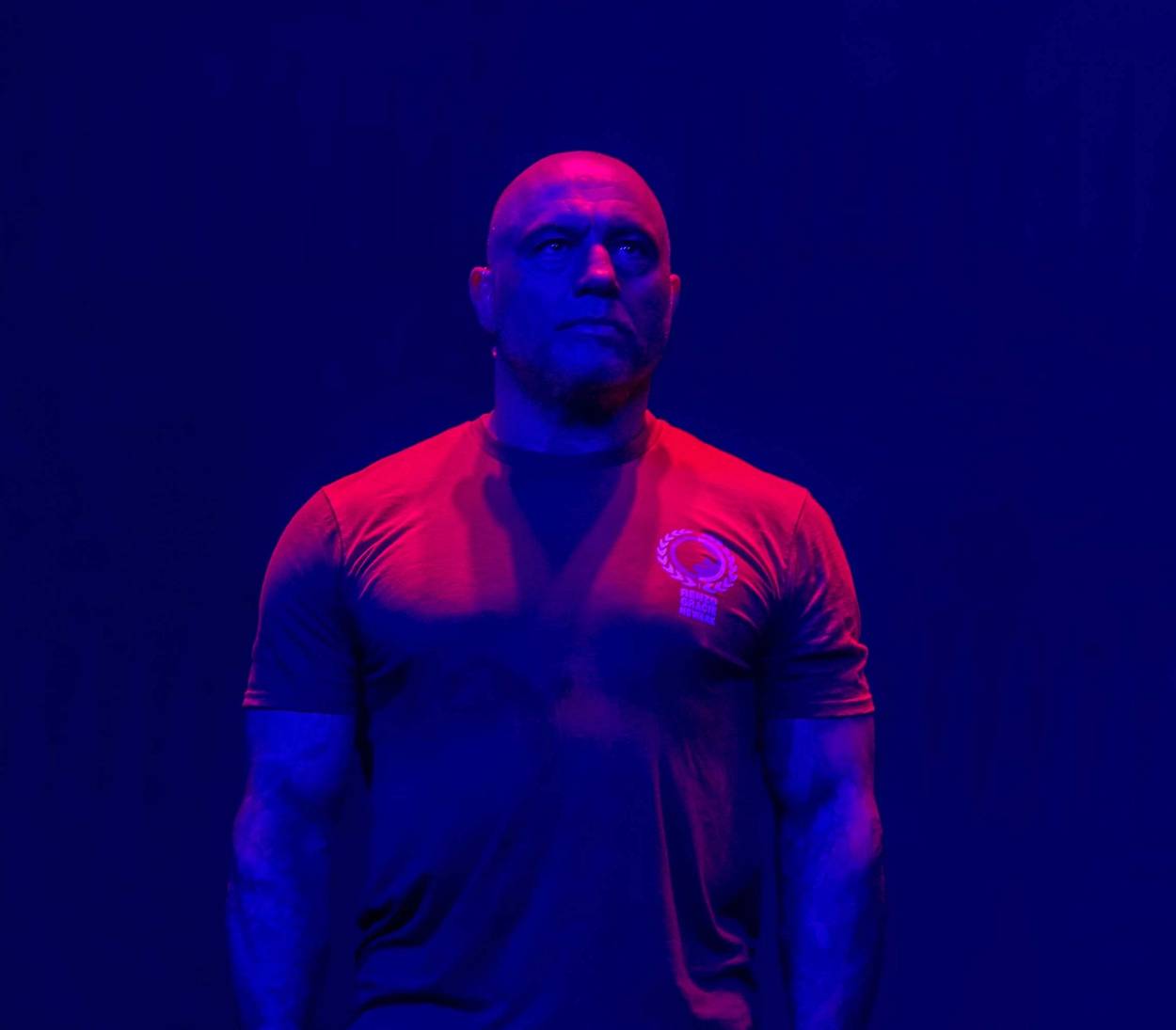

The Racist Joe Rogan

How the blue stack created the false impression that one of its COVID enemies also happened to be a vicious bigot

In-mid January, the blue stack—a powerful consortium of progressive activists, news outlets, major corporations, public health officials, and government apparatchiks who collaborate to marginalize ideological opponents—had its sights set on Joe Rogan, America’s most popular podcaster, who reportedly pulls in several times the viewership of the most watched shows on CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC.

Rogan’s crime at that time was to occasionally interview guests who were skeptical of the efficacy or safety of some COVID-19 vaccines and prevailing public health narratives in the United States. But after a barrage of attacks and attempts at cancellation—including demands from the White House itself that Spotify crack down on Rogan—his show remained on the streaming platform, frustrating his critics in government and competitors in media. The blue stack needed something else to prove that Rogan was too dangerous to remain on the service.

On Jan. 30, the popular progressive Twitter account @patriottakes posted a montage of Rogan saying the N-word followed by a joke he made comparing a Black neighborhood he was in with Planet of the Apes. “Multiple clips of Joe Rogan saying the N-word,” the maker of the montage tweeted. “This is who the right is defending.”

The video quickly went viral, with blue stack functionaries pointing to it as clear evidence of Rogan’s unsuitability for a public platform. Grammy-winner India Arie posted the montage to her Instagram, using it as justification for pulling her music from Spotify. The montage was uncritically picked up across a range of media outlets and became the subject of a segment from The Daily Show’s Trevor Noah.

“If there’s ever a video of you saying the N-word that many times, you better pray one of two things: Either you’re a Black person, or you’re a dead man from history,” Noah intoned.

Before long, Rogan posted an apology in which he tried to explain that each time he uttered the word, he never used it to describe or address or insult any human being, or otherwise used it in a racist fashion.

Missing from all this uproar was any context for the video that the Twitter account posted. In 13 years of conducting thousands of multi-hour interviews, Rogan apparently spent a total of 29 seconds uttering racial slurs and made a single ugly joke—hardly enough evidence to impugn his entire character or to claim, as Noah did, that Rogan is simply addicted to using racist language. Further, as the writer Coleman Hughes noted, imagine if the same account stitched together every joke that South Park has ever made at the expense of Black people—those unfamiliar with the show would come away thinking it was a fundamentally racist cartoon aimed specifically at African Americans, rather than a comedy that has spent over two decades skewering and offending every identity group in the United States.

In order to evaluate the actual context of Rogan’s remarks, you’d have to be able to watch the episodes yourself. But after consulting with Rogan, Spotify disappeared dozens of his episodes, including several that included the offending word. This made the blue stack’s attack more effective than it might otherwise have been: It was now able to use these episodes to attack Rogan, but because the episodes themselves are no longer available, the world is left with nothing more than a heavily edited montage of him repeating the slur. Because Spotify has a monopoly on full episodes of the Joe Rogan Experience (JRE), they are no longer on UStream or YouTube, where many of them originally premiered.

But after spending hours digging, I found that a user had uploaded many of the early JRE episodes to the Internet Archive, a site that collects material from around the web, including pages that no longer exist. The site does not include every episode in which Rogan used the word, but it does have many.

The earliest instance I found was in episode 4, which was pulled down during the February purge. In it, Rogan explains to producer Brian Redban how he thinks—of all things—that the power of words comes not just from the word itself but from the context of its usage:

I did an interview recently and I talked about the use of the word faggot. I was just explaining how what happened when I did the Spike TV thing, that they told me I could use any word except faggot when the show was uncensored. And I was like that’s so crazy because I’m not even talking to a person. I’m talking to a dog and some ants. That’s when I used the word faggot. And it has nothing to do with sexual orientation, you know? I know Louis CK actually has a bit on that, about how it never meant gay. And it didn’t. Anthony Cumia talks about it all the time on Opie and Anthony, about how faggot never really was a homosexual slur when we were kids. It was, it was not. I mean, but that’s true but it’s sort of not true because you knew that it also meant that. But people didn’t use it that way. That’s not what it meant.

And at the end of the day, like what language is supposed to represent is the context of your thoughts. You know? And the problem is when words get hyper-powered. Like cunt, or nigger, or faggot now. Faggot is like the new one. You know? Or love. Love’s a hyper-powered word too. You know, these words get hyper-powered and the word itself is more important than the meaning behind the word. You’re not, it’s not a true expression anymore. Like, I mean, a lot of people in relationships and you know, say you love me, tell me you love me, alright I love you. It’s like this weird fucking magic word thing that you have to say. It’s like, you should know by the way someone communicates with you whether or not they love you. They shouldn’t have to say this one word, shouldn’t have all this goddamned power, you know? The same thing with the word nigger and the same thing with the word faggot, now I guess. Because this gay guy told me when he was explaining this to me that I couldn’t say faggot, even if I didn’t mean anything, didn’t mean gay people, I couldn’t say it because I’m not gay. He said, but gay people could say because he goes, it’s our nigger.

It’s possible to disagree with Rogan about whether or not a particular word constitutes a slur so heinous that it should not be uttered under any circumstances, but it’s worth noting that the taboo against vocalizing them altogether is relatively new, as the linguist John McWhorter has argued. President Joe Biden used to say the word in full when he was in Congress; progressive standard-bearer Sen. Bernie Sanders wrote it in his book. In both cases, they were condemning racism, not espousing it.

Rogan did the same in episode 102, which was also removed from Spotify in February. While discussing a controversy over some anti-Mexican jokes made on the BBC program Top Gear, Rogan explained that he wasn’t against all offensive cultural humor but that he thought some of it crosses the line into racism:

That joke was terrible and then the other one, shitting on Mexican food. Mexican food is fucking awesome! If you go tell me that Mexican food is nothing but sick on it, they can’t do food can they, it’s just sick with cheese on it, haw haw haw haw. That’s fucking rude shit, man. That’s rude shit. And it’s okay if it’s funny.

But it’s not funny. You know? It’s like come on man, I can’t go with you. It’s not, it’s not enough. You know there’s not enough there to justify doing that. So what you have is two offensive jokes. One of them about food, not that big of a deal. But the other one, imagine waking up and remembering you’re Mexican, that’s just straight Polack jokes. That’s racist, man. That’s spic jokes, anything you want, that’s a nigger joke. It really is. I mean, they’re doing that to Mexicans.

Clearly, the only reason Rogan even vocalized the N-word in this episode was to encourage his audience to see what was wrong with it: You wouldn’t say this about African Americans, so why is it okay to denigrate Mexicans in the same way? His goal wasn’t to promote racism, but to widen people’s perspective and discourage bigotry. But several years later, that goal came up against the blue stack, whose goal was to censor Rogan for expressing skepticism about federal pandemic policies—and which figured out that the easiest way to achieve its ends was to portray him as perhaps the opposite of what he is in reality: a racist.

Martin Luther King Jr. imagined a future where “as the color differential fades, it will bring with it the racial point of view. Less and less it will be possible to speak with accuracy of Negro newspapers, Negro churches or the Negro vote. More and more, economic, social, and professional status will be more decisive in determining a man’s orientation than the color of his skin.”

The blue stack’s vision is the opposite of King’s. Its goal is not to discard race as the primary means of classifying human beings but to reinforce and magnify it. The Biden administration, the government wing of the blue stack, has adopted a posture of defending racially discriminatory college admissions policies, despite their deep unpopularity with the public. Some stack-aligned state governments like New York are distributing lifesaving COVID treatments based not on medical need but on racial prioritization.

Part of this utterly shocking development can be understood as the Democratic Party feeling threatened by racial depolarization. The GOP made real gains with minority voters in 2020; further gains might deny the Democrats the demographic majority they’ve long been promised. One of the problems with the blue stack’s racial fear tactics is that white racism has in fact been declining for decades. Hence, as the president claims that we’re on the cusp of “Jim Crow 2.0,” the blue stack is nevertheless forced to target its enemies for vocalizing a bad word rather than actually using that word to demean a human being.

The appeal of Rogan’s show has always been that he seems like an ordinary person trying to figure out the world by thinking aloud. He’s no political scientist, doctor, or subject matter expert. He’s just curious and open-hearted. If you subtract the celebrities he interviews from the show, the kinds of conversations you see on JRE reflect the same ones you might overhear at a construction site, at a diner, or in a family member’s living room. In the course of such freewheeling conversations, you’re liable to screw up and offend the person you’re talking to. You talk it out, you make up, and you move on.

Every interaction between human beings in the blue stack is treated as if Human Resources is listening in and waiting to pounce.

In the academic, corporate, nonprofit, and political hallways in which the blue stack operates, such comity and grace are typically unheard of. Every interaction between human beings in the blue stack is treated as if Human Resources is listening in and waiting to pounce, which just isn’t the sort of environment to which the average American can relate.

It’s certainly not how I grew up. I was blessed with friends from a diverse range of working- and middle-class backgrounds—Indian, Nigerian, African American, Mexican, Pakistani, white—in a town outside of Atlanta, where I was born. We talked with each other about all kinds of things, and sometimes even made the types of lighthearted cultural jokes of which the hall monitors at Media Matters wouldn’t approve.

On occasion, some of my friends even referred to my ethnicity as “Paki,” a term many blue stack busybodies would quickly note was used by nativist gangs in the United Kingdom that wanted to keep Pakistanis and other South Asians out of their country.

But when my friends used the term, I knew it was just a harmless demonym. The context mattered. Strictly policing language while forgetting the bigger picture—that the struggle against racism is a struggle to promote love and tolerance—gives the blue stack’s anti-racism a hollow, fundamentalist tone that creates a climate of fear rather than one of acceptance. Deep down, many Americans feel the same way.

Nobody can listen to Rogan conduct his interviews and honestly come away with the impression that he wants us to hate anyone, regardless of their ethnic background or political affiliation. While the blue stack’s army of scolds tells us they simply want a better world, it’s people like Rogan who are actually building one.

Zaid Jilani is a freelance journalist who has previously worked for UC Berkeley’s Greater Good Science Center, The Intercept, and the Center for American Progress. He also writes a newsletter at inquire.substack.com. He is a graduate of the University of Georgia and received his master’s from Syracuse University. He is originally from the Atlanta area.