Redeem Yourself

The Book of Ruth, which we’ll be reading this weekend, teaches us an important lesson about not waiting for someone else to come and save us

We have a redemption problem in this country right now. Whenever we find ourselves in darkness, usually of the political sort, we rush to identify a savior: a faultless leader who can save us from ourselves. In our binary good versus evil world, we wait for someone with fairy dust to sprinkle on our deep and pervasive problems and then suffer when the truth comes out. The promise is tarnished. The leader is flawed. He or she turns out not to be our redeemer. We are heartbroken. We take out Leonard Cohen’s Manual for Living with Defeat and hum a few bars. The pattern is entrenched. We will wait again.

I learned long ago not to wait. An enduring memory of elementary school came from a baritone of a sixth grade teacher who, when one of us would make a mistake, would bellow, “Redeem yourself.” He waited patiently for us to fix our errors, imparting in our impressionable minds that learning came from a never-ending cycle of blunders and corrections. The word “redeem” came to represent, for me, a higher order of knowledge directed by the self to the self. Don’t wait for someone else to clean up your mess. Clean it up yourself.

Later, in my theology years, the term “redeem” meant something wholly other. God was Rock and Redeemer, a twinned expression communicating divine power and stability coupled with the capacity for forgiveness. God redeemed us even when we did not deserve it. This was grace. Suddenly the word had less to do with self and everything to do with Other, with a mystical overlay that lacked the technicality of 6th grade math corrections.

In Hebrew, the word for redemption, “geula,” represents a time in the future: aspirational, almost mythical, and remote. When praying for redemption, we are not packing our bags but latching on to the swell of hope’s optimism. Spiritualizing redemption took it far from the here and now of everyday existence, stretching out the concept across an intangible acre of world beyond human reach. Until…

Until, that is, I read the Book of Ruth with a critical eye and noticed that variations of the term redemption appear twenty times in its four short chapters. The Hebrew Bible gave us an entire book to contemplate the real meaning of redemption—and it has a lot less to do in its verses with God and a lot more to do with human intervention. A “go-el,” a redeemer, is a person who releases a woman from the bonds of widowhood through levirate marriage, cojoining a parcel of land with the bereft family who used to own it and returning a woman to a place of former dignity. It returns a family to emotional and fiscal security. In Leviticus, it is also used dozens of times to refer to human-driven actions like redeeming land or servants. In the Torah portion of Behar, it is used no less than 19 times.

The Biblical lexicon Brown-Driver-Briggs defines a “go-el” as a kinsman who does his part to execute family responsibility. It is also a payment of value assessed, of consecrated things by the original owner, of redemption from an orphan status. These, too, all involve the human as redeemer. Of course, in the Bible, God redeems the Israelites from slavery and is referred to in biblical poetry as the world’s redeemer, but the preponderance of Biblical references direct us to human intervention so deep that it catalyzes a complete transformation of status.

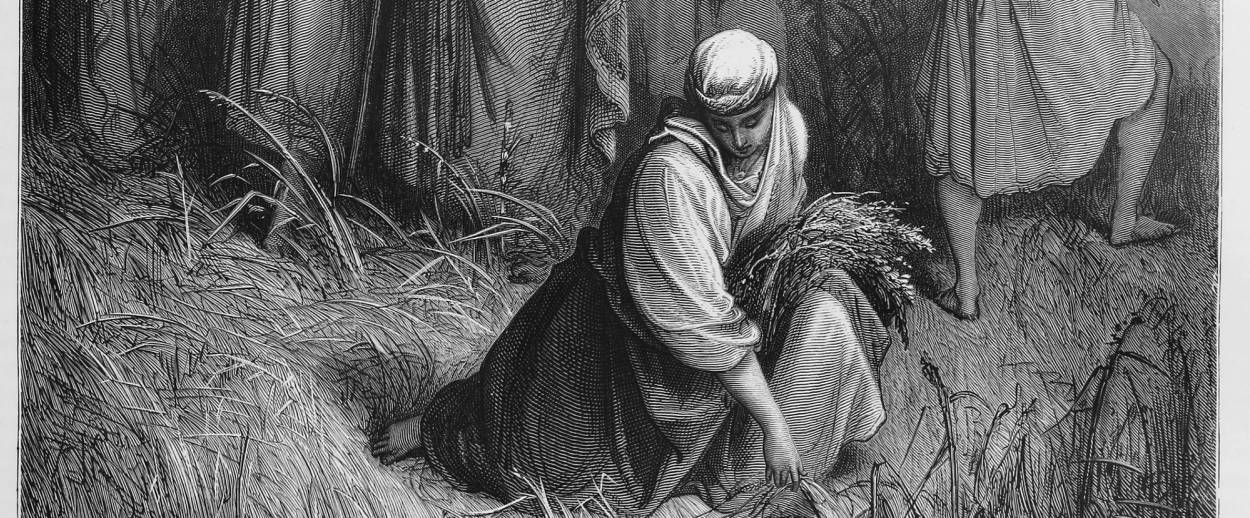

Naomi, in the belief that Boaz was the closest kinsmen who could perform this ritual, induced Ruth to doll herself up in the middle of the night, go to a threshing floor at harvest time and present herself to her generous patron. Instead of using their proper names, the text shifts and refers to them simply as man and woman, encountering each other in the rawness and anonymity of potential urges. The two then play a game of identification.

“Who are you?” [3:9] Boaz asked Ruth, a reasonable question at this late, strange hour. Innocently, Ruth introduces herself as his handmaid and then adjures Boaz: “Spread your robe over your kinsman, for you are a go-el—a redeemer” [3:9]. The spreading of a robe, as we know from Ezekiel 16:8, is a gesture of marriage, blanketing a woman with protection and care. But Boaz disabuses Ruth. He is not her closest redeemer (even though she is ultimately right). The next of kin, when given the chance, was willing to purchase the family’s land but unwilling to marry Ruth, “lest it damage his estate” [3:6] To the offer of property, he boldly replied, “I will redeem” [3:4] but when told about Ruth, he sheepishly refused and thus is given no name in a book where everyone is named. This verse of refusal contains a variation of the term “redeem” five times, as if to suggest that a chance to transform the life of another was right there and waiting, but, as is so often the case, we turn away, just as he turned away.

Lest we think that the Book of Ruth uses this term in its legal context alone, the last use of the term “redeemer” is uttered by the female chorus of Naomi’s friends: “Blessed be the Lord, who has not withheld a redeemer from you today!” [4:14] as Naomi holds a precious infant, her grandson. This is a reference to Boaz, while hinting at two others who redeem Naomi’s life: Ruth and Oved, the baby. Ruth transformed Naomi through her friendship and dedication. Grandchildren, too, are redeemers to those who suffer the penalties of age and the weight of loss. Just watch a grandparent look lovingly into the eyes of a baby, and you understand what redemption looks like.

A midrash tells us that we read the Book of Ruth to teach us about the power of loving-kindness. This is true but not true enough. The drumbeat of the word “redeemer” in its verses suggests even more than kindness, the way transformation suggests more than change. Redemption does not mean waiting for a savior. It means being a savior. It means working for deep change without the charisma and bravado of the ego-fed leader. Ruth’s cast of characters inspire us to contemplate what it means to redeem one’s own life and the lives of others by standing up and taking charge of what is within our control to change. Bereft of her country, sons and husband, Naomi courageously picked herself up and returned home from Moab, we read in chapter 1:6. We must pause at this moment to honor her for not waiting for someone else to take her misery away.

Shavuot is a good time to offer thanks to those who have helped us change. This short book suggests that with our short lives we can change our circumstances and change the lives of others, not only on the grand, dramatic universal stage but in our more intimate interiors: among family, friends and strangers. Who in your immediate circle could benefit from your love, your counsel, your generosity, your patience? That such acts can transform worlds takes us to the book’s end, where we tumble from one generation to another until we arrive at King David. Family redemption can turn into political redemption. We can only hope and think of the poet Kay Ryan’s words, “The day misspent, the love misplaced, has inside it the seed of redemption. Nothing is exempt from resurrection.” Who is your redeemer? Who have you redeemed?

Ruth changed her world and then the world with a crazy proposition. She left her home, left her family, left her gods, and left her country on a gamble. Like Naomi, she, too, did not wait for someone to make her life better. She took risks. Those risks paid off slowly. When she traveled the distance, she understood that if she could change herself, she could help bring redemption to others. Through that, she was redeemed by Boaz creating an active cycle of human redemption that led to King David. He, too, was a redeemer, but not without serious flaws. So perhaps this Shavuot we, too, will stop having the same old conversations centered on everything that is wrong while waiting for some magical cure from outside of ourselves. Human redemption is flawed and messy. It does not wait. And from the pages of an ancient book, it is calling you.

Dr Erica Brown is an Associate Professor at George Washington University and the director of its Mayberg Center for Jewish Education and Leadership.