In the fall of 1959, I bought my father a birthday gift of a three volume, boxed set of Carl Sandburg’s Lincoln. When he opened the wrapping paper, he raised the books to his lips and kissed them, as if he were kissing his Sabbath prayer book. He read through the volumes slowly, penciling in comments in the crowded margins. “What extraordinary prose,” he wrote on one page. “A poet, a thinker, a deep soul,” he wrote on another.

Lincoln was his idol, the great man who had saved the union.

My dad loved Lincoln’s story: the poor, gangling boy who walked a mile to read a book; the young man who pulled himself upward by dint of hard work, eventually becoming a lawyer, a Congressman, and the 16th President. The story resonated fully with my father, Morris Laufgraben, who, in 1920, at the age of 12, had come to America from the Polish shtetl of Rozvadow knowing only a couple words of English. He sold ladies shoes by day and, by going to school at night, became, like Abe Lincoln, a lawyer in America.

I thought about the books and my dad’s marginalia when I walked through Lincoln and the Jews, an exhibit at The New-York Historical Society open through June 7. At every moment I asked myself: Did my father, during his lifetime (he died in 1963), know anything at all about his idol’s Jewish connections?

Marking the 150th anniversary of the end of the Civil War and Lincoln’s assassination, the show opens with statistics that contextualize the Jewish position as a minority in Lincoln’s America. For instance, when Lincoln was elected president, only 150,000 of the country’s 31 million people were Jewish— less than one-half of 1 percent.

As the exhibit moves forward in time, the Jews—who began as peddlers doing business on credit—prospered, becoming clothiers, merchants, printers, lawyers, bankers, photographers, politicians, and physicians,who even treated the President’s eyes (Dr. Isaac Heilprin) and feet (Dr. Issachar Zacharie).

We learn that Lincoln most probably bought clothing from Julius Hammerslough’s store in Springfield, Illinois, and that Abraham Jonas, a lawyer and early political supporter, was a close confidant. They were part of a circle of attorneys who often faced each other in the courtroom. There is a letter from Jonas written in December, 1854, encouraging Lincoln to run for a U.S. Senate seat in 1855. As it turned out, he did run but lost by a few votes.

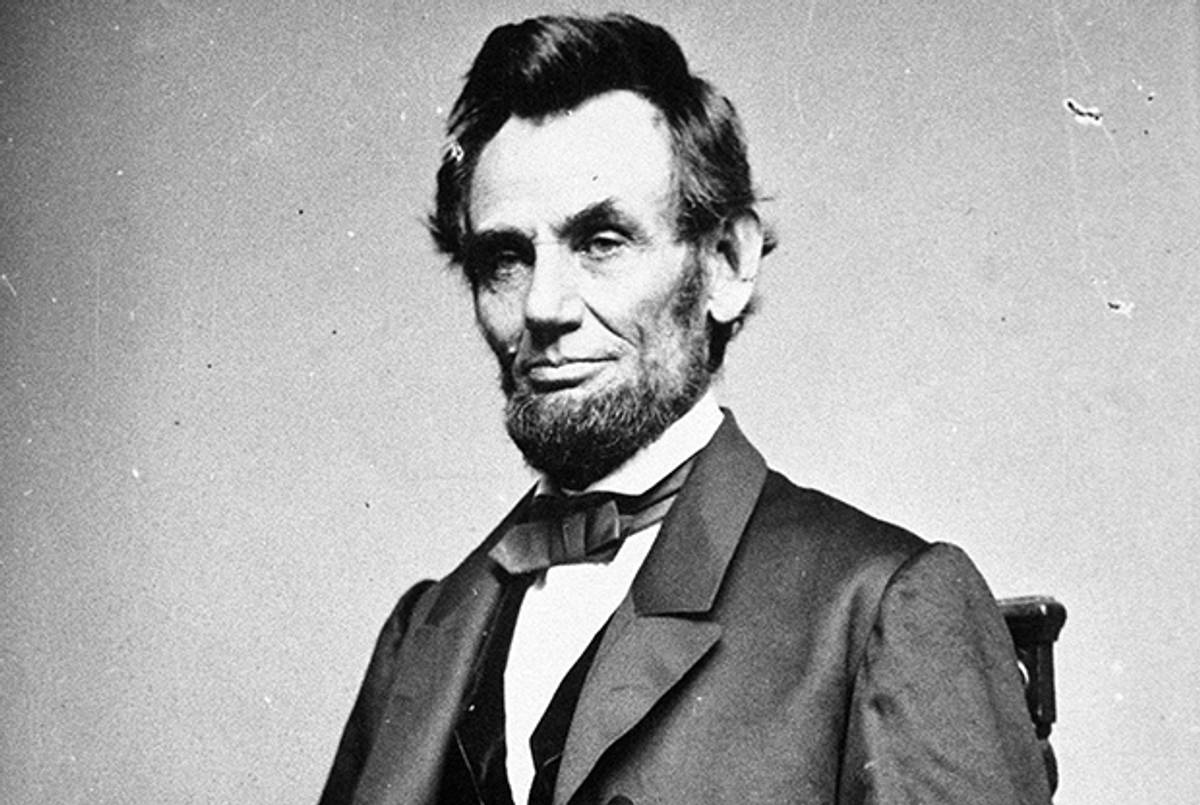

There are two portraits of Lincoln taken by photographer Samuel G. Alschuler who substituted a jacket with a velvet lapel for Lincoln’s linen coat, to upgrade his image. Alschuler took the first photo of Lincoln with a beard on November 25, 1860. An eleven-year-old girl, the text says, had urged Lincoln to grow the beard so his face would not look “so thin.”

There’s another letter from Jonas (December 30, 1860) cautioning Lincoln to beware of impending violence and danger at his inauguration. Lincoln listened to his friend, traveling through Baltimore at night and entering Washington, D.C. secretly.

During the Civil War, American Jews, like the rest of the nation, were divided, with some 3,000 fighting for the Confederacy and more than 7,000 for the Union. This was true in the Jonas family where five sons lived in the south and fought against the Union.

Even though many of Lincoln’s generals and cabinet members were anti-Semites, Lincoln stood his ground. He rescinded General Ulysses S. Grant’s General Orders No. 11 of December 17, 1862, “banning Jews from the vast area under his command,” and appointed an Orthodox Jew as an Assistant Quarter Master with the rank of Captain.

After Richmond fell on April 2, 1865, Lincoln met with Secretary of War John A. Campbell and Gustavus A. Myers, a prominent Jewish attorney from Richmond aboard the gunboat USS Malvern on April 5.

Only eight days later, on Good Friday, then the fifth day of Passover, Lincoln was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford’s Theatre. He lay in a coma for some nine hours, surrounded by 15 doctors, including Charles Liebermann, a Russian-born Jewish surgeon. Lincoln died the next day, on the Jewish Sabbath.

Inspired by the book Lincoln and the Jews by Jonathan Sarna and Benjamin Shapell, the exhibit ends with actors reading from eulogies by rabbis mourning Lincoln’s death.

Several rabbis compared Lincoln to Moses. Both, they said, saved their people from slavery and both did not make it into the promised land.

My father would have agreed.

Roslyn Bernstein, an arts and culture reporter, is the author of Illegal Living and Boardwalk Stories and Professor Emerita at Baruch College and the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY. Her most recent writing project is a young adult novel set in Jerusalem in 1961 during the Adolf Eichmann trial.