Remembering Ruth Gruber

The American journalist, humanitarian, and photographer whose images captured the harrowing journey of Jewish immigrants aboard Exodus 1947, has died at the age of 105

Ruth Gruber, a legendary photojournalist, humanitarian, and author, died on Thursday in her New York City apartment. She was 105 years old.

Born to Jewish immigrants in Brooklyn, Gruber became the youngest PhD in the world at the age of 20, writing her dissertation on Virginia Woolf at the University of Cologne. In 1935, she became the first foreign correspondent to travel to a Siberian gulag and the Soviet arctic. Although she is known primarily as an author and journalist, her groundbreaking work as a photojournalist spanned more than five decades on four continents.

In 1944, during World War II, Gruber stewarded the ship Henry Gibbins on a secret U.S. government mission that brought nearly 1,000 Jewish refugees from Europe to Fort Ontario in upstate New York. This was the only attempt by the United States to shelter Jewish refugees during the war.

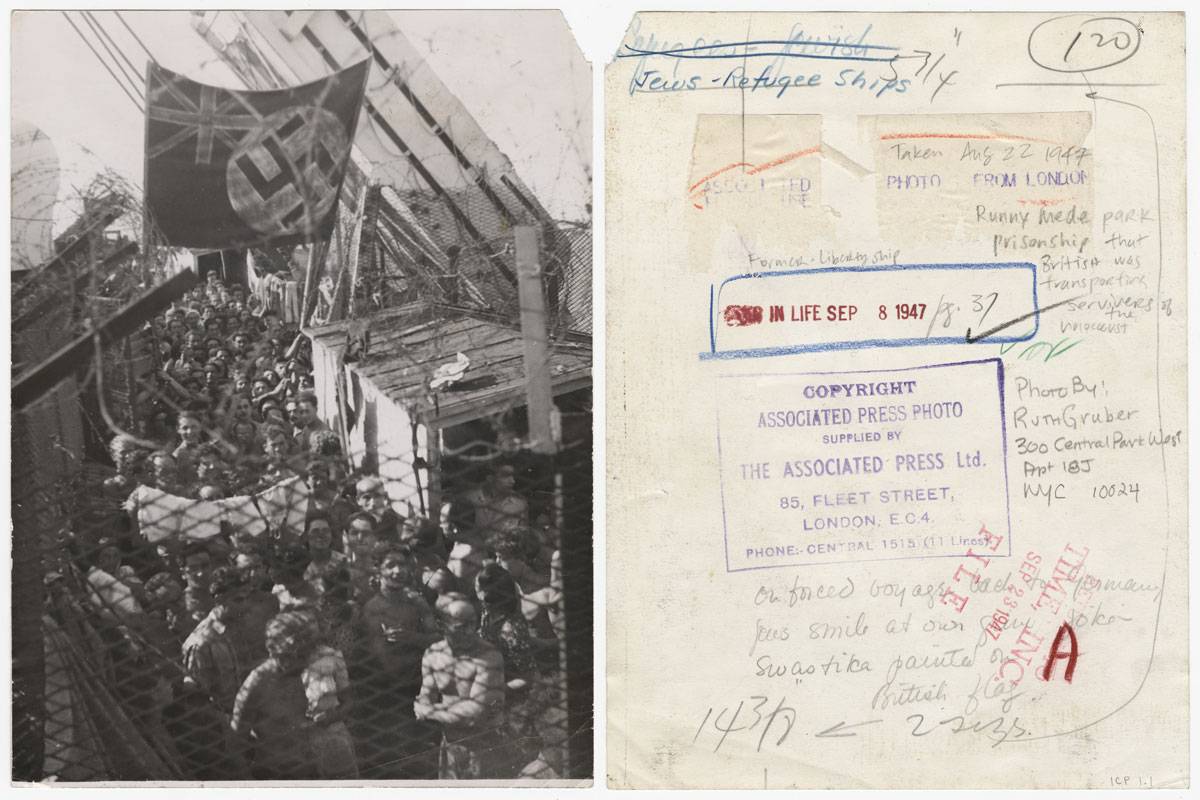

In 1947, Gruber’s exclusive photographs documenting the harrowing voyage of the Exodus 1947—a ship carrying 4,500 Jewish refugees that attempted to break the British blockade on immigration to Palestine—were sent to thousands of newspapers and magazines, and radically transformed attitudes toward the plight of Jewish refugees and Holocaust survivors after the war.

Following the establishment of the state of Israel, Gruber photographed the waves of immigrants who poured into the new country, while continuing her commitment to documenting the condition of Jewish communities in North Africa and throughout the world. In the 1980s, she returned to Ethiopia to document the civil war.

In 2011, at age 100, Ruth was honored with the International Center of Photography’s Cornell Capa Lifetime Achievement Infinity Award. A retrospective exhibition of her work as a photojournalist was presented at ICP in 2011 and continues to travel. Working with her to organize the exhibition was one of the great gifts and privileges of my life. Unhindered by her advanced age, Ruth read and commented on every word in the exhibition and was an involved partner in the organization of the show. She was thrilled to see her life’s work as a photographer featured in an exhibition at a photography museum, a first for her.

During a visit to Ruth’s Upper West Side apartment a few years ago, when I reported the news that her exhibition would travel to Alaska (to her great delight), I overheard her assertively negotiating a speaking fee for an upcoming presentation. She was 102 years old. She hung up the phone, looked at me, and said, “always know your worth.”

Ruth Gruber did not get married or have children until she was in her forties; she kept her name, which has already had so many bylines and books attached to it. As we surveyed her archive of interview transcriptions, prints, negatives, and contact sheets, I wondered how she managed to take single engine planes into the hinterlands of the Soviet arctic, Siberian gulag, and remote Alaska Territory, yet always managed to look glamorous. She scolded me, “It’s not difficult to put on lipstick.” When I asked her the secret to her longevity—she was sending emails and writing books as a centenarian—she replied, “never, never, never, never retire.”

Ruth took some of the earliest known color photographs of the Alaska Territory, in the early 1940s. I will never forget the moment that she first held a color print of her Kodachrome slides, at age 100. The original slides had faded and a master printmaker at ICP, Nikol David, painstakingly color-corrected the digital images and created stunning prints. Ruth held the 14 x 11 inch print in her hands, looked at me, smiled wide and said, “Wow! It’s beautiful, isn’t it? It’s really gorgeous. I never knew how beautiful my color work was until just now. Don’t you think that’s something?”

Indeed. It was.

Last week, Ruth Gruber, who was born before women had the right to vote, left her apartment for the last time to cast her vote for the first woman president. Ruth dedicated her life to fighting injustice and advocating for human rights and the basic dignity of all people, focusing her efforts on the plights of refugees and stateless people, women and children.

The principles she lived by—to fight fascism whenever it rears its head, to work hard every day, to advocate for those without a voice, especially refugees and stateless people, to stand up to bullies and to know your worth—have never been more resonant than they are today. We must honor her tenacity and heroism by continuing the fight.

Previous: The Great Gruber

Vox Vault: Lady Gruber

Maya Benton is a curator at the International Center of Photography.

Maya Benton is a curator at the International Center of Photography.