The Rule of Midwits

A set of decentralized, ideologically driven selection mechanisms is propelling the decay and collapse of American institutions

While Republican intellectuals are finally facing the problems created by the Democratic Party’s institutional capture of colleges, the HR bureaucracy, and public education, the Democratic campaign to defend these redoubts is proving remarkably unpopular with the electorate. Take the recent Virginia governor’s race between Republican Glenn Youngkin and Democrat Terry McAuliffe. The Youngkin campaign could be summed up by an attack ad that simply quoted McAuliffe: “I don’t think parents should be telling schools what to teach.” Consequent polls found overwhelming support for Youngkin among parents of K-12 students, up to an estimated 17-point gap. Youngkin won.

With administrators seemingly so unpopular with the public, one might wonder why Democrats are so eager to defend them. The reason appears to be little more than a dogma, a crude mimicry of the Reagan Republican emphasis on free markets. Instead of the free-marketeer, the Democrats’ figure of affection is the bureaucrat, the middle manager, the good-old insider who knows how an institution works and is tied everlastingly to it. The threat of greater democratic participation in setting school curricula or determining COVID measures leads Democrats to cry “authoritarianism,” “fascism,” and “coup,” just as reflexively as Reaganites once called the public provision of services “socialist.” The New York Times captured this well when it portrayed laws establishing some degree of parental control over public school curricula as “a War on Democracy.”

The key term for understanding the ferocity of the Democratic attachment to mid-level managers is “midwit.” A midwit is typically described as someone with an IQ score between 85 and 115; more colloquially, it describes a person with slightly above-average ability in any domain—someone who is able to pass basic qualifications and overcome standard hurdles but who is in no way exceptional. For a dominant political party, this is an obvious constituency and exactly the type of person you want on your side. While midwits often are preferable to dimwits for obvious reasons, they’re also preferable to an elite (those with exceptional abilities but who may not wield power) that might one day decide to overturn existing structures and ways of doing things.

While competition for authority might, in some contexts, be well worth the value that a member of the elite contributes, this is rarely the case in incumbent political institutions, most of which depend for their survival on restricting intellectual input. Even if incumbent institutions could attract elites initially, elites would eventually abandon them, either to work in institutions less burdened by historical constraints or else in fields that are dominated more by objective rather than subjective measures of skill and accomplishment.

To understand this phenomenon better, it helps to look at a chart of college majors ranked by average IQ.

IQ is also not an all-encompassing measure, but a reasonably predictive, best-for-now heuristic without many alternatives. This chart also provides averages only: There are of course geniuses in early childhood education and dimwits in economics. But some fields, on average, clearly skew toward midwits.

These degree breakdowns can also be projected forward into the labor market: Software engineering jobs frequently require computer science or mathematics degrees, doctors require medical degrees, and so on.

But what really give teeth to this observation are the selection systems that dominate particular fields, explicitly filtering out candidates from both the top and bottom of the IQ scale. Job qualifications typically filter out candidates from the bottom, while restricting opportunities for free, creative, lucrative, and independent work filters out those from the top.

Software companies, for example, have a high demand for elite labor and compensate accordingly. They explicitly brand themselves as solving difficult problems in fast-paced environments staffed by “A-player” colleagues, engage actively to recruit top talent from top universities, and subject applicants to difficult technical tests. Naturally, they tend to attract people who studied computer science, natural sciences, and mathematics, or even just iconoclasts who have both the ability and ambition to solve abstract and highly technical problems.

In each subgroup of the political class—candidates for office, staffers, activists, journalists—the primary selection mechanism is not technical competence but strict ideological conformity, as it is in the aforementioned incumbent institutions: It takes some basic degree of ability to learn the mantras, avoid missteps, and punish dissenters. Thus was the data scientist David Shor fired from his progressive analytics firm for sharing peer-reviewed research demonstrating that violent protests have a history of hurting progressive electoral prospects; and when the University of Chicago geophysicist Dorian Abbot was invited to give a lecture at MIT on climate change, his lecture was canceled because of his opinions on affirmative action. Restrictions on freedom of conscience can be a sticking point even if they don’t result in getting sacked or canceled, as demonstrated by the trajectory of liberal dissenters like Bari Weiss, Peter Boghossian, and Zaid Jilani. That their message has drawn large, sympathetic audiences is a significant development.

On the empirical side, while there don’t appear to be direct measures of, for example, the average IQ among granular ideological factions, we do have some indirect evidence. Significantly, the professional fields that are most politically touchy, and which are also (uncoincidentally) left leaning, fall neatly into the midwit range: journalism (communications), education, social science, business administration and management, and public administration.

This is not a new phenomenon. The historical analogs for this effect are often referred to as “Lysenkoism,” named after the Soviet biologist Trofim Lysenko. Rejecting well-evidenced genetic findings, Lysenko made absurd, demonstrably false claims about farming, including the hypothesis that exposing crops to poor conditions would increase future yields because “future generations of crops would remember these environmental cues,” and nearby seeds would not cause resource scarcity because “plants from the same ‘class’ never compete with one another.”

Lysenko is the standard bearer for pseudoscience driven by confirmation bias. But his false claims were not at all random or founded in ignorance: Each of his lies formed part of a coherent argument for communist assumptions. He denied that genes exist on the basis that believing they do could prove a “barrier to progress.” He dismissed contrary evidence presented by Western scientists as “tools of imperialist oppressors.”

There is no shortage of this phenomenon in contemporary times. Think of the denial of diversity in human intelligence, of physical differences based on biological sex, of standardized testing as race-neutral, and of the empirical data behind the efficacy of corporate diversity training and measures to combat the “gender pay gap.” With the benefit of hindsight, it is widely known how Lysenkoism ended: The implementation of his “research” in reality helped facilitate the starvation of tens of millions of people from Ukraine to China through manmade famines.

Of course, not all Democrats hold Lysenkoist beliefs, just as not all Republicans are anti-vaccine or deny the existence of anthropogenic climate change. But the salience of these beliefs across U.S. political, corporate, nonprofit, journalistic, and academic institutions demonstrates that ideologically convenient Lysenkoism persists on both sides of the aisle. The main difference between liberals and conservatives, as the political scientist Richard Hanania points out, is organization. As Hanania says:

There are two ways to lie in politics. Let’s say Side A wants to spend more on government, and Side B wants to spend less. Side A might exaggerate the benefits of investing in poor communities, and Side B might tell a story about how tax cuts for the rich will pay for themselves. This can be called directional lying, with each side trying to convince you of something, and this is how politics pretty much worked until the last few years.

Republicans, because they are tribal and not ideological, do not punish their politicians for non-directional lying, or simply making things up … Trump mostly governed like a typical Republican, and his administration pushed for things like less spending on entitlements. Republicans meanwhile have been running ads accusing Democrats of wanting to cut Medicare. …

Liberals say really false things like “men can get pregnant,” “police are killing large numbers of innocent black men,” and “poor people are more likely to be fat because of food deserts.” Yet these are lies (or more usually, kinds of self-delusion) that you would expect from people who’ve adopted crazy ideological commitments.

An existing model of institutional power describes institutional decisions as arising from conflicts between factions. Recruiting, HR policy, and governance are not just procedures for choosing the best person for the job or promotion; they are means of choosing the person who would most benefit the faction making the choice. In other words, it’s politics all the way down.

With this in mind, midwits and the ideological conformity they favor can spread through incumbent institutions fairly easily even without any organized effort. How? First, incumbent institutions disproportionately select for midwits; second, ideologically conformist midwits select for others of the same ideology, which can be done through hiring decisions, HR law, or employee activism; third, the selection process is amplified further by incentives—because ideological conformity benefits midwits, they change procedures to elevate themselves over their less conformist but more productive colleagues; fourth, the increase in ideological conformity skews selection further toward midwits.

This cycle helps explain why incumbent institutions become stagnant or decline, and eventually become incapable of doing what they were created to do.

The vast majority of these processes do not require Machiavellian planning, but they are responsible for consequences that benefit no one. Take the attacks on advanced classes and specialized programs in primary and high school education occurring in blue areas like New York City, California, Boston, and Oregon. In service of the ideology that demands equality of outcomes between demographic groups, self-proclaimed progressives are seeking to eliminate redistributive, public sector education programs that have been shown in New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere to benefit primarily poor students and immigrants.

Unlike what some prominent conservatives seem to think, this doesn’t really represent “a plan to take over America.” Instead, it’s mostly a case of incentives aligning for midwits to act according to their own emotional and political biases, which also happens to advantage their political benefactors.

Left-wing ideology and incumbent institutions have become almost synonymous, just as Democratic politicians and media figures have become closely associated with ideas like ‘bureaucracy’ and ‘stagnation.’

This model helps explain how left-wing ideology and incumbent institutions have become almost synonymous, just as Democratic politicians and media figures have become closely associated with ideas like “bureaucracy” and “stagnation.” And in a sanitized political bubble like this one, there is very little need to engage in formal democracy. Sure, there are primaries and elections every couple of years, but these tend to make up a fraction of a bureaucrat, professor, NGO staffer, think-tanker, or journalist’s time. Instead, their engagements with “democracy” are mostly relational—filling out paperwork, putting arguments in writing, arranging meetings, and so on. Their idea of democracy is shaped not by the democratic process itself (i.e., public deliberation), but by feedback from bureaucracy, an often artificial and unnecessary appendage of democracy. Consequently, when movements push policy that circumvents this appendage, they are actually completely right to perceive it as an existential threat to their way of life. This mentality, more than “wokism,” “neoliberalism,” or any other ism, cost Terry McAuliffe his chance at reclaiming the governor’s mansion.

On the Republican side, this theory helps explain why most of their attempts to address institutional disadvantages are failing. It’s actually much easier to reverse the consequences of an organized plan than to reverse an emergent process: Simply remove the leaders from power and wield political force. So far, that’s exactly what Republicans have been trying to do.

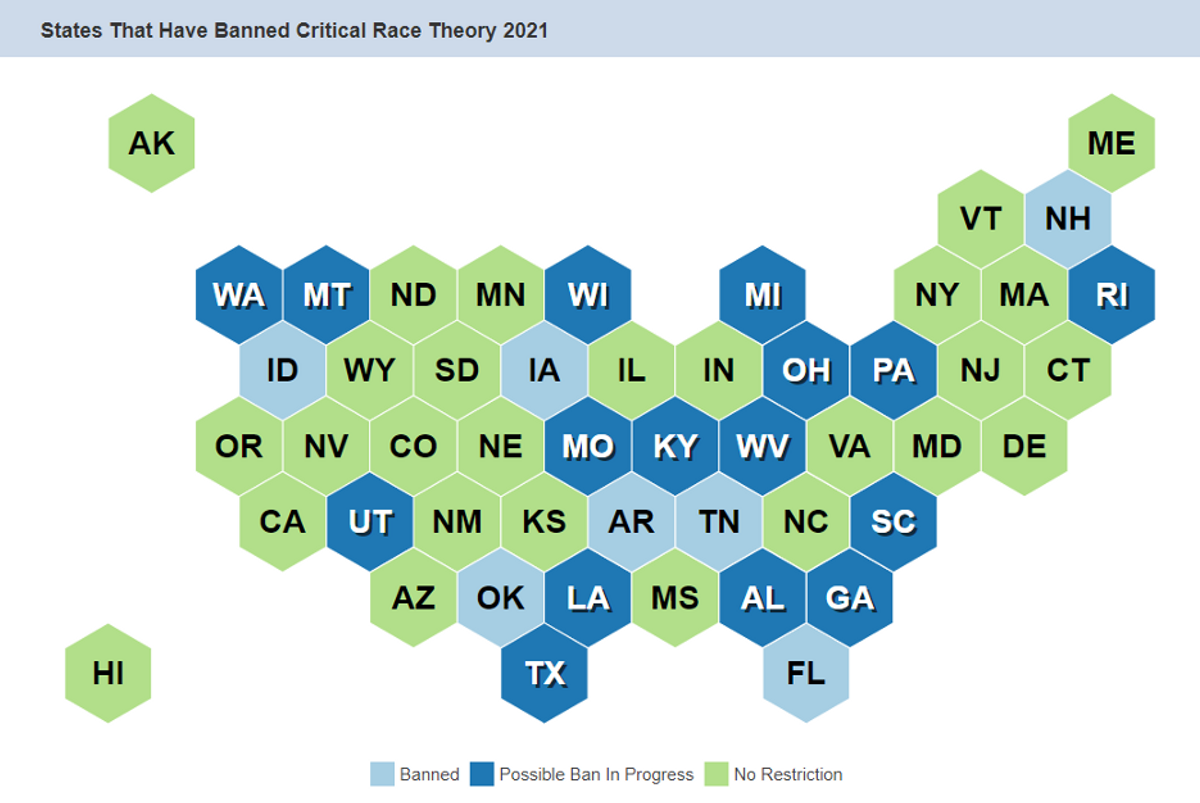

Republicans put both Donald Trump and Glenn Youngkin into office. They’ve passed broad anti-critical race theory (CRT) laws, threatened to break up Big Tech companies, and have even proposed legislation to make it easier. But as Marshall Kosloff put it, “If you broke up Amazon into six different companies, AT&T stock from the 1980s, all six of those companies would also not serve Parler ... It’s just the fact that a certain part of the country that is realigning away from their political beliefs has control over these institutions.” Similar arguments can easily be made for other Republican ideas. Even if anti-CRT laws are passed, left-wingers who would have taught it have plenty of other ideologies to choose from, which they can use to educate students the way they want.

So: Are Republican elites just stupid? Well, no. Firstly, elites—whether Democrat or Republican—can easily shelter themselves. Anyone in at least the upper middle class, with an average income around $200,000 per year, can pay for private schools or whatever other pathways lead away from the problems caused by the rise of midwits. More importantly, the United States is a two-party system, which means that Republican coalitions enjoy the inverse of what Democratic coalitions get. This is the one exception to the idea that midwits are always preferable to dimwits in a political movement. As New York Times columnist Ross Douthat wrote in reaction to Hanania’s argument:

One arguable takeaway from this analysis is that being an intellectual attached [to] the GOP is a really depressing business *unless* your faction can seize control of a GOP WH, in which case you’ll face relatively few constraints on action from your base.

The most important takeaway from this model might be that the American status quo is not really in all that much danger; it is actually incredibly stable. This doesn’t mean that polarization won’t increase, or that elected offices won’t continue flipping back and forth. What it implies is that the incentives and institutions that caused this cycle of institutional decline and failure will continue to self-perpetuate, despite the efforts of third parties and intellectual movements, whether elitist or populist, to take over. This cycle will perpetuate itself because it is driven by an incredibly resistant set of decentralized incentives that incorporate built-in reactions to the most common challenges. The common mistake of the “anti-woke,” “depolarization,” and “never-Trump” factions is in underestimating the phenomena they claim to oppose.

Brian Chau (aka Cactus Chu) is a writer and publishes the pseudonymous newsletter Meta Politics.