See How It Runs

‘Maus,’ at 25, Goes ‘Meta’

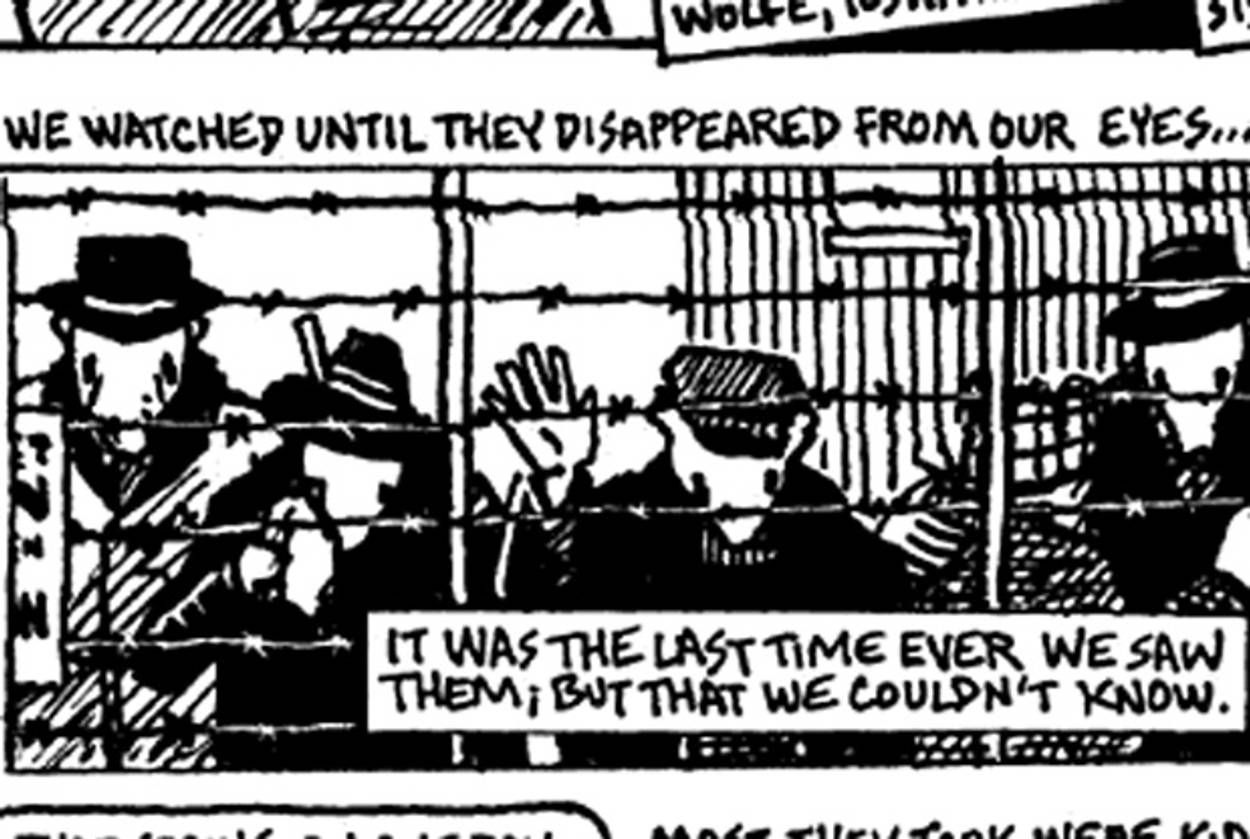

It’s the 25th anniversary of the publication of “My Father Bleeds History,” the first volume of Art Spiegelman’s masterpiece Maus (most of it had already been serialized in RAW, a comix magazine run by Spiegelman and his wife, Françoise Mouly). And we fans of it are being treated to MetaMaus, a multimedia extravaganza that fills in a ton of the details surrounding the making of Maus: sketches, annotated frames, transcriptions of Spiegelman’s conversations with his father. MetaMaus dropped Tuesday; tonight, Spiegelman appears at 92nd Street Y.

The best thing on MetaMaus I’ve read so far comes, unsurprisingly, from The New Republic’s Ruth Franklin, author of a fine study whose primary insistence is that a myopic obsession with getting the actual facts of specific Holocaust stories exactly right frequently gets in the way of appreciating the artful depictions of larger, more important, sometimes detail-immune truths about the overall event. (I wrote about Franklin’s book last year.) “What MetaMaus makes clear,” Franklin argues, “is that Maus, like the works of W.G. Sebald, exists somewhere outside of the genres as they are normally defined: We might call it ‘testimonially based Holocaust representation.’ But no matter what it is called, it gives the lie to the critics of Holocaust literature (as well as certain writers of it) who have insisted that either everything must be true or nothing is true.”

There’s also this great story:

The question of how truthful Maus can be is perfectly illustrated by the minor kerfuffle that broke out when the second section of the book was published in hardcover and promptly made its way to the New York Times best-seller list—in the fiction column. In a letter to the New York Times Book Review (reproduced, naturally, in MetaMaus), Spiegelman protested: “I shudder to think how David Duke … would respond to seeing a carefully researched work based closely on my father’s memories of life in Hitler’s Europe and in the death camps classified as fiction.” One editor reportedly responded, “Let’s go out to Spiegelman’s house and if a giant mouse answers the door, we’ll move it to the nonfiction side of the list!” But the Times, following Pantheon (which had listed it as both history and memoir), ruled with Spiegelman.

In a totally different context, I noted, “For all the artistic liberty Spiegelman takes, Maus is entirely faithful to what happened. The Jews are not anthropomorphic mice, as is frequently said; rather, they are Jewish men and women, who are merely drawn as mice. (They have tails, but they do not have a yen for cheese.)”

We reserve the highest place for artists who make us see things we think we know in a completely different way. Spiegelman literally made us see the Holocaust differently, and so the 25th anniversary of his achievement is something to celebrate.

Art Spiegelman’s Genre-Defying Holocaust Work, Revisited [TNR]

Related: Higher Truth [Tablet Magazine]

Marc Tracy is a staff writer at The New Republic, and was previously a staff writer at Tablet. He tweets @marcatracy.