Soleimani U

A new academic center in Caracas named after the Iranian mass murderer is the latest node in Tehran’s soft power network in Latin America

For decades, Iran has patiently sought to export its Islamic Revolution to Latin America. Alongside Iranian embassies, one academic institution stands out as a bastion of Iran’s influence operations in the region: Al Mustafa International University, which has branches in over 50 countries, and which the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned in 2020 for its role in Iran’s propaganda efforts, including the provision of material support for the training and indoctrination of Shiite militias. With an $80 million annual budget, Al Mustafa is one of Iran’s leading propaganda outlets. Its robust budget enables it to spread Iran’s revolutionary message far beyond the walls of its campus.

The university’s latest achievement is the establishment of the Cátedra Libre Qassem Soleimani, or the Qassem Soleimani Chair for Sociocultural and Geopolitical Studies in Latin America and the Middle East, a center that was inaugurated in November 2020 at the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela in Caracas. The late Qassem Soleimani was the commander of the Quds Force, the elite unit of Iran’s Revolutionary Guards’ Corps in charge of overseas operations. As such, Soleimani was chiefly responsible, during his tenure, for the establishment of regional, pro-Iran Shiite militias, multiple attacks on U.S. troops in Iraq, and, more recently, Iran’s deployment in Syria to save the Assad regime from collapsing. Soleimani bears responsibility for the murder of hundreds of thousands of Syrians and the forcible displacement of millions of refugees, leading to the ethnic cleansing of large swaths of Syria’s Sunni areas.

Soleimani was assassinated in a targeted U.S. drone strike in January 2020 in Baghdad, but the Biden administration now has different priorities. Its Iran policy is laser-focused on the country’s nuclear program. Countering Iran’s international propaganda, by contrast, has never been a high priority for this or even previous administrations. The White House should reconsider.

As the scholars Kasra Aarabi and Saeid Golkar wrote in February 2021, “Al-Mustafa’s objective is to enrol [sic] and train non-Iranian students interested in Iran’s revolutionary Shia Islamist ideology, or in becoming Shia clerics, to disseminate and advance the ideological goals of Iran’s Islamic Revolution.” Founded in 2007 in Iran’s holy city of Qom from the merger of previous religious seminars that catered to foreign students, Al Mustafa carries the torch of Iran’s Islamic Revolution through hundreds of blogs, online materials, journals, and other publications, with classes in dozens of languages that train tens of thousands of students, including foreign converts. The university also maintains a global network of affiliated seminars and centers. Many of its graduates have since returned home as ordained Shiite clerics, assuming leadership of local Al Mustafa-affiliated and Iranian-funded cultural centers and NGOs and serving as force multipliers for their alma mater.

What began in the early 1980s as a subtle effort to propagate revolutionary Iran’s worldview through mosques and cultural centers is increasingly loud and visible, thanks to Iran’s transnational alliances with hard-left movements and regimes in Latin America, which help facilitate Al Mustafa’s proselytizing and propaganda work. Thanks to the zeal of its acolytes and Iran’s funding, a vast regional network is now in place. Revolutionary fellow travelers from communist Cuba to the Castro-Chavista regimes in Bolivia, Nicaragua, and Venezuela have given Iran greater access, freedom of action, and resources to consolidate its outreach and leverage local anti-American sentiment to serve its own interests.

It’s no surprise that Iran’s foray into Latin American universities has scored its biggest success in Venezuela. Caracas has been Tehran’s closest ally in the region since the late Hugo Chavez and his Bolivarian brand of anti-Americanism seized power there in 1999. Relations flourished under Chavez’s tenure, and especially when Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was Iran’s president from 2005 to 2013.

When sanctions were crushing Iran’s economy prior to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the 2015 nuclear deal, Venezuela assisted Iranian efforts to evade U.S. sanctions. More recently, as U.S. sanctions hit Venezuela’s top leadership and energy and banking sectors, Iran came to the rescue, swapping refined petroleum products for Venezuelan gold and launching an airlift to assist Venezuela’s beleaguered refinery sector.

Iran and Venezuela have also cooperated in the realm of illicit drug trafficking, with Venezuela serving both as a transit country for drug shipments eastward, and as a way station for Hezbollah’s money laundering activities, as evidenced in numerous court cases prosecuted by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) under Project Cassandra, whose main targets were Hezbollah illicit finance operations and their enablers.

For Iranian propaganda especially, the Venezuelan regime since 1999 has been a godsend. HispanTV, the Iranian Spanish language news channel, and TeleSur, Venezuela’s Bolivarian propaganda network, share resources, including journalists. Iran has also established an Al Mustafa cultural center in Venezuela, the Centro de Intercambio Cultural Iran Latino America, or CICIL (recently shortened to CICL), where an Al Mustafa representative permanently resides. Cooperation between Al Mustafa and Venezuela’s academic sector began long before the establishment of the Cátedra Libre Soleimani, the culmination of a two-decade-long joint venture to disseminate anti-American propaganda that serves both regimes.

Al Mustafa-sponsored institutions are an echo chamber for Iran’s narrative of resistance to so-called imperialists and oppressors, usually embodied by the United States and Israel, which resonates more in parts of Latin America than a specifically Islamic message would, winning support from old-fashioned communists and nativist, indigenous separatists. Among these groups, anti-Americanism is an easy sell.

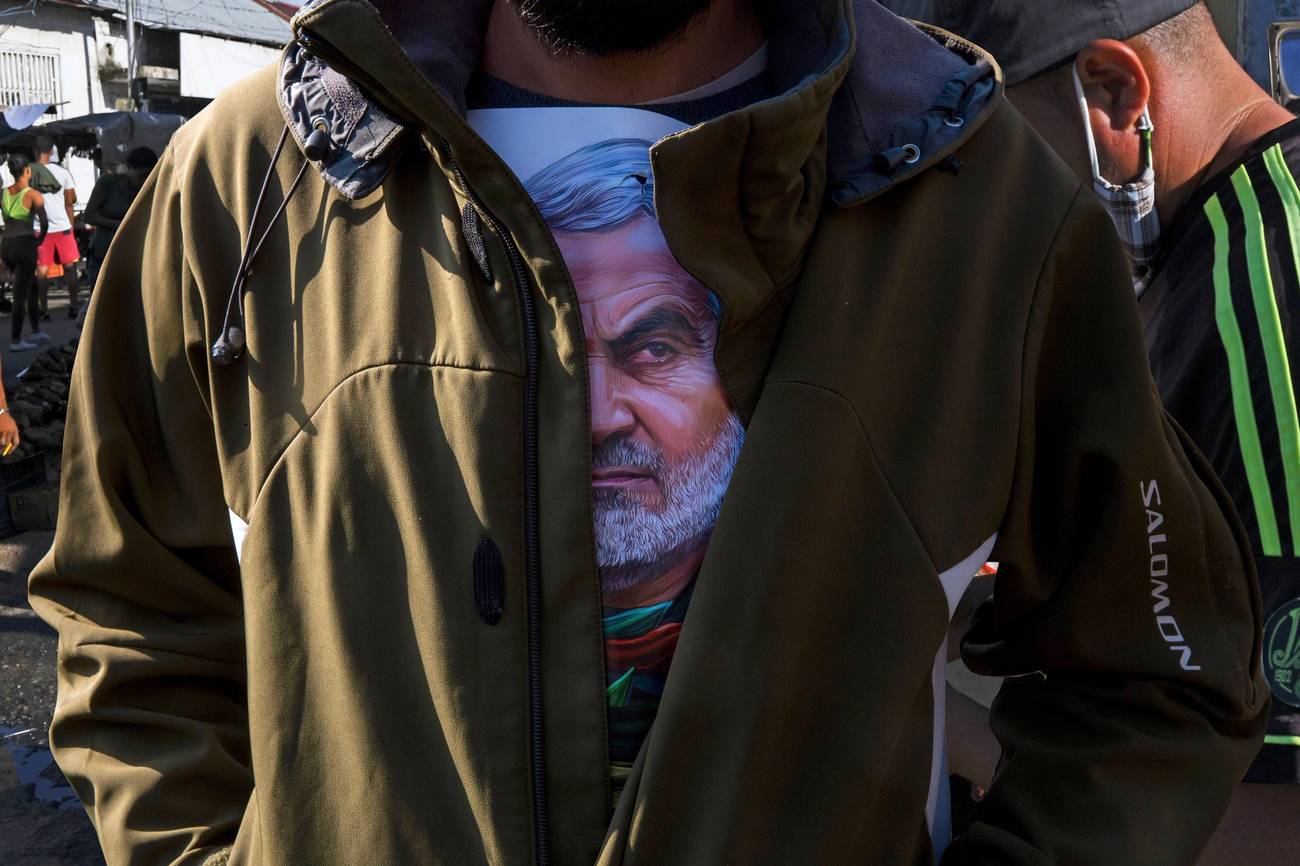

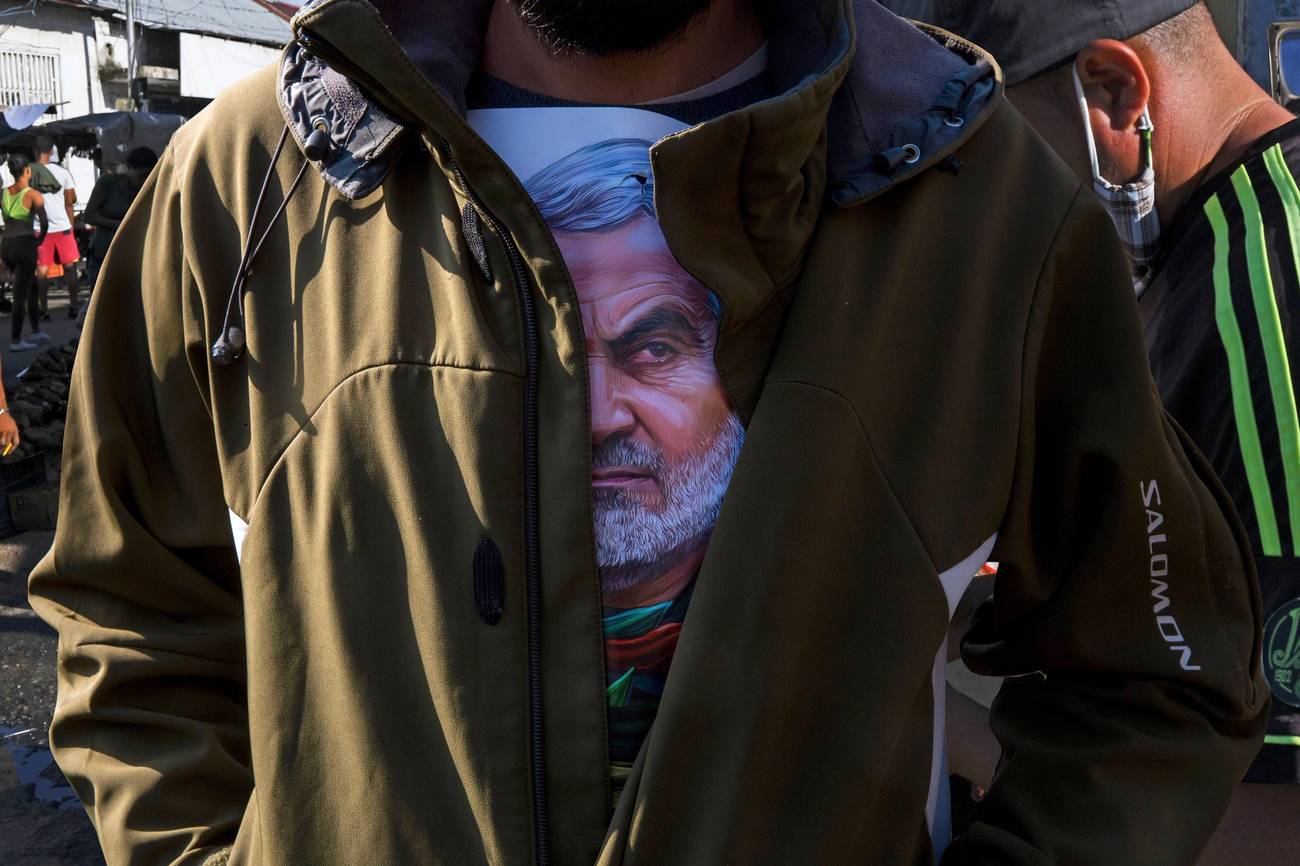

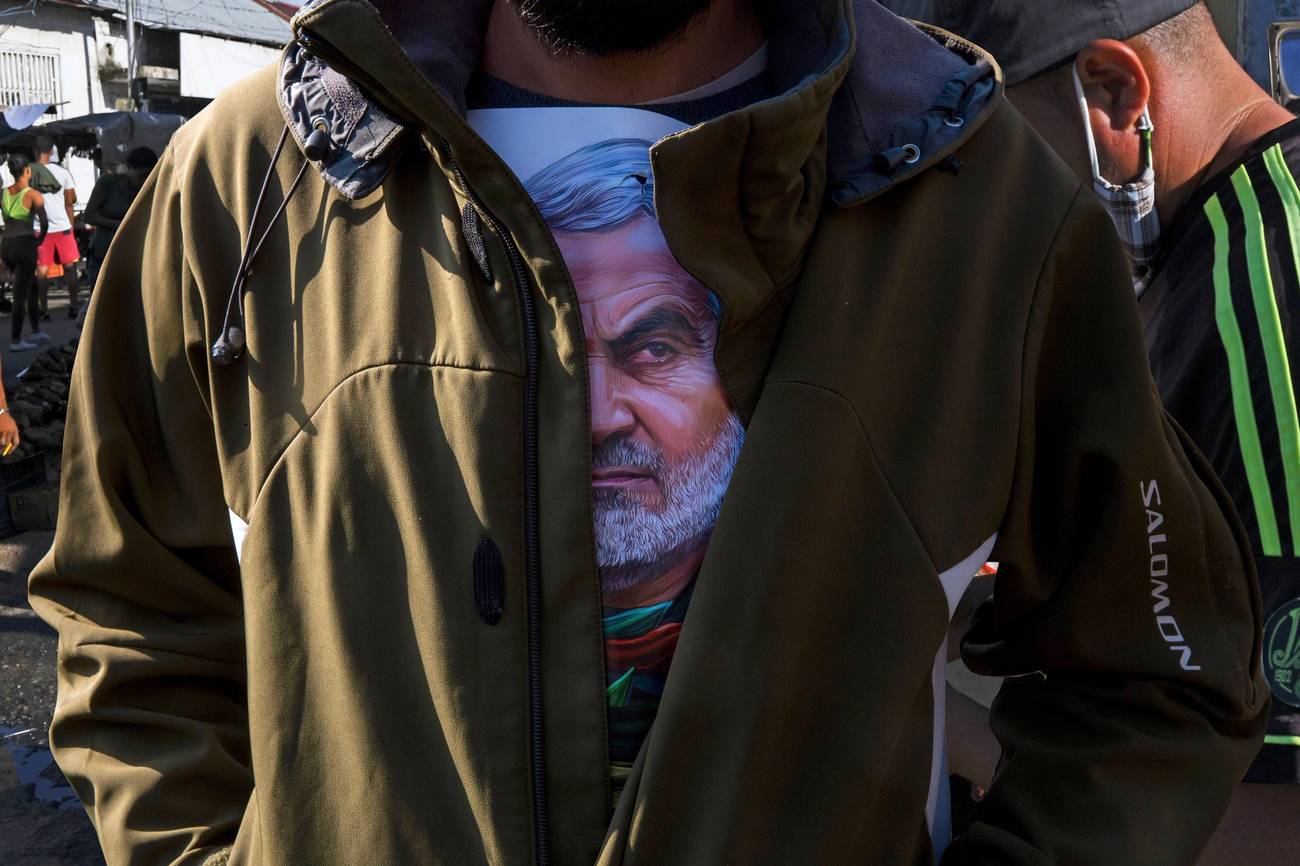

Since Soleimani’s death in 2020, Iran has lionized him as an iconic hero of the “Resistance,” depicting him for Latin American audiences as a latter-day Islamic Che Guevara. This theme reverberates in Spanish-language, pro-Iran propaganda: In a January 2022 blog post republished by TeleSur, Chilean author Pablo Jofre Leal, a collaborator of Al Mustafa University’s Hispanic languages department, Islam Oriente, and other Iranian proxies in Latin America, evoked Che’s words to describe Soleimani: “The highest level which the human race can aspire to is to be revolutionary.” Soleimani, he added, was “an authentic revolutionary.” The mandate of the Soleimani Chair at the Cátedra is to explore themes that are part of Soleimani’s “legacy” as “a hero and martyr in the anti-imperialist struggle.” As co-director Ramon Medero explained in a video launching the Cátedra, Soleimani is “a martyred hero who immediately became a symbol of justice and a paradigm to be followed by all oppressed people of the world.”

A permanent presence on the Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela campus not only allows Al Mustafa a permanent foothold in regional academia; it also helps Al Mustafa advertise and expand its Spanish-language platforms, facilitate travel for its employees under the guise of academic exchanges, and distribute revolutionary literature, which Al Mustafa publishes through Latin American partners, often under the banner of Islam Oriente.

Nor is the new Cátedra the first of its kind. The Argentina-based Centro de Estudios Árabes e Islámicos (Center for Arab and Islamic Studies, or CEIAP), for example, is run by Al Mustafa graduates. Although there are no additional chairs or academic centers sponsored by Al Mustafa in the region, there are numerous cultural centers in addition to the aforementioned CICIL in Caracas: one in Chile, one in Peru, one in Bolivia, at least two in Argentina, three in Brazil, one in Colombia, one in Costa Rica, two in Ecuador, one in El Salvador, one in Mexico, and one in Cuba. There are also the Al Mustafa-sponsored publishing houses, foundations, media platforms, and academic journals that cater to those attracted to Iranian revolutionary ideology, and even Shiite Islam.

The addition to this regional galaxy of academic centers, with their affiliated scholars, will give new life to Iran’s efforts to expand its soft power outreach. Academic partnerships established with local universities create opportunities for Iranian-backed conferences, seminars, classes, lectures, webinars, and publications. They also give access to captive audiences—students who might not be drawn to Al Mustafa-operated mosques and cultural centers on their own might be co-opted instead through classroom lectures and campus-based political activism.

Iran has lionized Soleimani as an iconic hero of the ‘Resistance,’ depicting him for Latin American audiences as a latter-day Islamic Che Guevara.

Washington has done little to counteract Al Mustafa’s and Iran’s influence operations in Latin America, focusing instead on Iran’s hard power in the Middle East. Part of that is understandable: During the Cold War, Washington sought to deter Moscow’s aggressive expansionism mostly through nuclear and conventional military deterrence. The establishment of Soviet cultural centers as proxies for the spread of propaganda in the West and the Third World is not remembered as an especially central element of the Cold War, especially as their influence could never quite match the mass global appeal of American commercial culture. But they did play an important role, and Soviet revolutionary ideology did catch like wildfire over large parts of the globe, in part through the cultural and psychological appeal of its propaganda.

Treating Iran-affiliated mosques and cultural centers in Latin America as harmless venues for spiritual fulfillment dangerously underestimated the ideological playing field. Washington should do more than periodically mention the existence and activism of Iranian propaganda networks in Latin America, which the U.S. Southern Command’s annual Posture Statement does for Congress. The Biden administration has so far neglected to act on the Treasury Department’s December 2020 designation of Al Mustafa. Doing so would allow Washington to target its subsidiaries and seek to cut off their funding sources. It should also identify Iranian agents acting under the cover of Al Mustafa cultural centers and educational institutions and add them to the list of designated individuals.

The U.S. government should also work with social media platforms to flag many of Al Mustafa’s outlets that spread Iran’s propaganda, including on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube. In November 2020, U.S. law enforcement agencies seized 27 internet domain addresses controlled by outlets affiliated with the IRGC. The Department of Justice should expand this action and target Al Mustafa’s platforms as well.

The U.S. Department of State should also work with regional allies in Latin America to ensure that Al Mustafa’s traveling missionaries are denied entry into their countries. Their activists should be on watchlists for visa applications and should be denied entry into the United States.

More broadly, the United States needs to rethink its own counterinformation strategy. It can’t just assume that because it won the Cold War, American ideas of liberal, democratic capitalism have forever prevailed in its own hemisphere. America’s own backyard still provides fertile soil for anti-American and revolutionary ideologies, which it neglects at its peril. Washington will not effectively counter Iranian soft power unless it takes it seriously, and actively seeks to contain the regime’s efforts to spread its revolution abroad.

Emanuele Ottolenghi (@eottolenghi) is a Senior Fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a nonpartisan research institute in Washington, D.C.