Squirrel Hill Taught Me About Community

A moving remembrance of growing up as one of the few African-Americans in Pittsburgh’s ‘shtetl’ neighborhood, where every Shabbat is a special day, and every day can be Shabbat

Three years ago, I was asked to deliver the keynote address at the American Jewish Committee annual dinner. I chose to use that opportunity to explain what was so special about my childhood neighborhood, Squirrel Hill in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. After the attack in Squirrel Hill this weekend, just a short walk from the front door of my childhood home, a number of people contacted me about that speech. It is being reprinted here because I think that the world should know just how special a place Squirrel Hill has always been. What follows is the text of that speech.

***

When I was asked to speak about bringing communities together, my first reaction was that, I’m no expert on this subject. But I happened to be asked on an unusual day for me and my family. It was a rare day for us because it was the only Saturday in the year when neither of my two teenage sons had a football or basketball game. They wanted to do something we never get to do—they wanted us all to go see a movie together.

They were disappointed, however, because my wife had made a prior commitment. She explained that she could not go with us because she had promised to volunteer at the Diwali festival for my son’s high school. Diwali, of course, is the Hindu festival of lights. “But Mom,” my son Claude said, “you’re not even Indian.”

My sons were disappointed—but not surprised. Last month, a few Korean moms at our sons’ school rescheduled their monthly coffee to accommodate my wife’s new work schedule. She’s not Korean either.

What she happens to be is all too rare, I think. While she is, in fact, an African-American, she views her community—our community—much more broadly than that. In the 30 years in which we have been married, I never once heard her refer to our community as “the African-American community.” Instead, she always referred to “our community” as the circles in which we live our daily lives.

So it occurred to me that while I may not be an expert on bridging communities, I’m pretty sure I am married to one. So I asked her, “Angie, how do you suppose you came to view your ‘community’ this way.” To my surprise, she pointed at me and said, “I think I got it from you.”

While I was flattered, I rejected this praise. Her response was, “Who do you think took me to my first Seder, my first bar mitzvah, my first bris?”

This led to a conversation that, after 30 years of marriage, I had never imagined having with my wife. We talked about our feelings with respect to the killings of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and of Eric Garner in Staten Island. We talked about our mutual fears of raising two African-American teenage boys in a town—Palo Alto, California—where they are about the only African-American boys for miles around. We also talked about the kind of community in which we wanted to raise our boys.

By the end of that conversation, it became clear to both of us that her appreciation for the breadth of her community didn’t come from me at all, but instead, came from the values I experienced and internalized in the shtetl in which I was raised.

Yes, I said “shtetl,” because that is the only way to describe the very special place I grew up.

As my closest friends know, I spent my early childhood in the Terrace Village Housing Projects of Pittsburgh. As a boy, I never thought much about my relative circumstances in life; we didn’t have a television, and all I really knew was the neighborhood in which I spent every day.

But one day that neighborhood changed—suddenly and dramatically.

It was my father’s birthday, and all I recall was how the candles on his birthday cake were the only source of light in our basement apartment. I also recall the fear on the faces of my parents as we huddled together in our kitchen. You see, my father’s birthday was April 4, and on that April 4, in 1968, Dr. King was assassinated. Those birthday candles were our only source of light because our neighborhood, Terrace Village, erupted in flames, rioting, and despair that night.

Shortly after that, my parents were determined that we would move out of the ghetto. But unfortunately, in 1968, families from the ghetto were not welcomed everywhere. Except for one very special place. In the summer of 1968, my family moved from the Terrace Village Housing Projects of Pittsburgh’s Hill District, to an even older “ghetto”—the historically Jewish neighborhood of Squirrel Hill.

Squirrel Hill was like a completely different world to me. If you know it, you know that it is the heart of Pittsburgh’s Jewish community. To me, it was the first real “community” in which I’ve ever lived. Everything I’ve ever needed to know about being a member of a community, I leaned from my friends and neighbors in Squirrel Hill.

When the rest of Pittsburgh seemed closed to my parents and our family, our neighbors in Squirrel Hill welcomed us in. From our very first days in Squirrel Hill, we were embraced as both very different, but very integral members of a thriving, diverse and healthy community.

While I learned a lot of things growing up in Squirrel Hill, I think I can point to three important life lessons about bridging and building communities from the people of Squirrel Hill. And I can express these lessons in three phrases:

1. Never let your first taste of latkes be by surprise;

2. Every Shabbos is a special day, and every day can be Shabbos;

3. Kosher salt is salt.

Please bear with me as I explain what I mean by these three important life lessons.

Never let your first taste of latkes be by surprise.

When we first moved to Squirrel Hill, our neighbors made every possible effort to make us feel welcome and part of the community. One of our first visitors eventually became my closest friend. His name was Michael Goldbach, and he and his mother came to our house to welcome us. Michael was exactly my age, and loved baseball as much as I did. Michael’s mom brought us a bunch of treats from her kitchen. As it happened, my mom was cooking when Mrs. Goldbach dropped by, and she invited the Goldbachs to stay and eat with us. I remember very clearly that they graciously tried everything my mom had prepared. I, on the other hand, was really reluctant to try anything Mrs. Goldbach had brought with her: blintzes and latkes.

Had I been more open minded, I would have discovered some of my favorites foods years before I actually did. I can’t explain my original reluctance, other than the fact that these foods were unfamiliar and strange. They caught me by surprise.

What does this have to do with bringing communities together?

Well, I think that much of what we are seeing in places like Ferguson and Staten Island, in Cleveland, Milwaukee, and even in places like Dresden, Germany, is a tendency of people to be more like I was, and less like Michael Goldbach’s mom.

Do we have police encountering people in communities where their only experiences with “those” people are ones that take them by surprise?

Are these surprises always occurring in settings that are beyond their choosing? (Well, by definition, a surprise encounter has to be one that occurs under circumstances that are not of our choosing.)

Could we reduce the “Fergusons” and the “Staten Islands” of the world by being more like Mrs. Goldbach? I think so. I think that the idea behind community policing is to get police to encounter the people of the communities they protect in less confrontational, more congenial circumstances. And when we meet people where they are, and show a genuine interest in who they are, it does more than just bring people of different communities together. It forms new communities, and changes those of us in those communities.

Mrs. Goldbach was so typical of many of our neighbors in Squirrel Hill. Mrs. Goldbach didn’t wait to encounter us; she came to us, and embraced us. She made up her mind early on that we were part of her community, and she determined the time and the place of her encounter with us. In other words, she planned to expand her notion of community. She made it her purpose.

That doesn’t mean that our plans will always be successful. Sometimes they will be met with skepticism, suspicion or worse. But if we don’t take the chance, then our encounters with the unfamiliar will be under circumstances not of our choosing. They will catch us by surprise.

To be honest, not everyone in Squirrel Hill was a “Mrs. Goldbach.” But there were more people like her, and many of them were shaped by the community in which we lived, just as I was. And I may never have learned this if not for the second of my three lessons, namely, that:

Every Shabbos is a special day, and every day can be Shabbos.

In Squirrel Hill, even to this day, Shabbos is the quietest day of the week. With a large observant and Orthodox population, there are very few cars on the streets, and most of the shops are closed. Most—but not all.

And this is an important point about Shabbos and Squirrel Hill. While a large percentage of the people of Squirrel Hill observe Shabbos, it is precisely because they observe it that you can see the true character of the people there. On Shabbos, because the majority of the people are at home, or at services, the otherwise hidden diversity of Squirrel Hill becomes readily apparent. It was on Shabbos, more than any other day, that I learned just how many people were just like us, minorities—refugees from other communities—who were taken in by the people of Squirrel Hill.

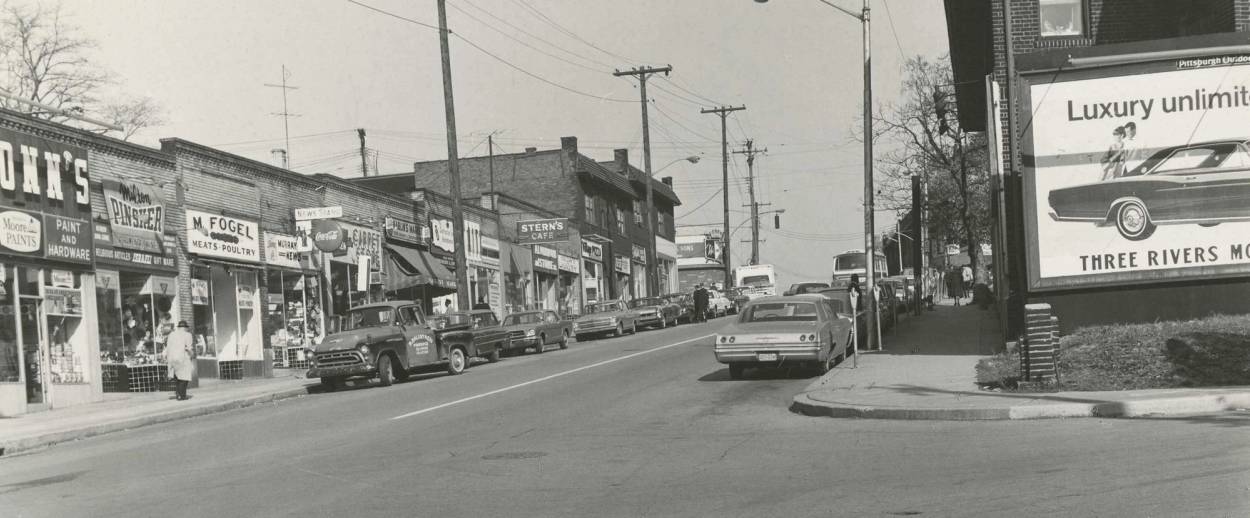

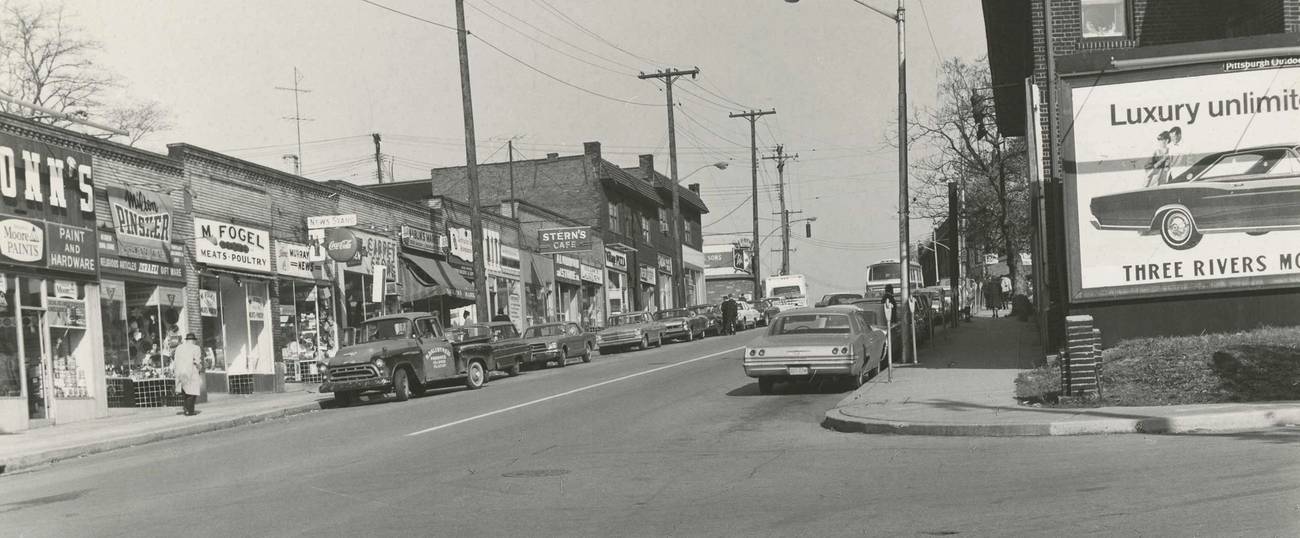

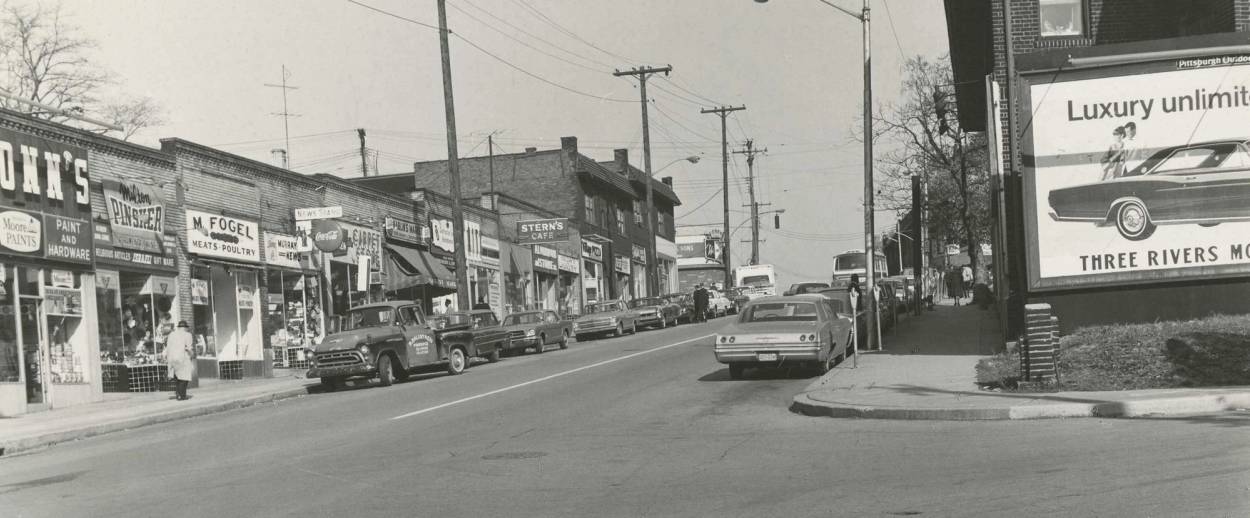

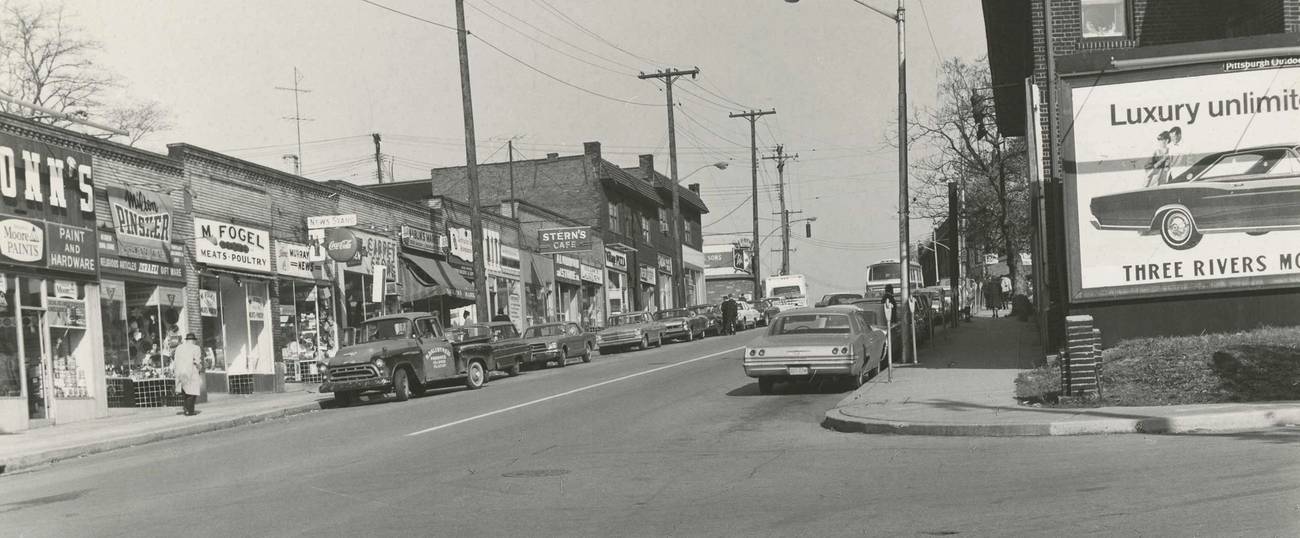

While all of the kosher butcher shops and bakeries were closed on Saturdays, those of us who did not observe Shabbos patronized the shops that were open. The best hoagies, pizza and Chinese food to be found anywhere in Pittsburgh was available in Squirrel Hill on Saturdays. In fact, Murray Avenue, the main shopping street in Squirrel Hill, looked like a true melting pot on Saturdays. The true openness of the people of Squirrel Hill was on full display on Saturdays.

But one Shabbos, more than any other, stands out in my mind. It was late on a Friday evening in 1968. As the sun began to set, my little sister expressed a craving for strawberries. My dad tried to explain to her that the shops had already closed, but she really wanted them, and he wanted to get some for her. So he piled me, my sister, and my brother who was just 3 years old at the time, into our car to drive to a different neighborhood to get strawberries.

While we were successful in getting the strawberries, we picked up something else as well. A car full of three young white males began following us, and followed us all the way back to our home in Squirrel Hill. Suddenly, as we drove up to the front of our house, these men pulled their car in front of ours and jumped out. They had a bat and a tire iron in their hands, and as my dad jumped out of our car to confront them, they beat him, crushing the left side of his face, and leaving him to bleed all over the windshield of our car, all in front of his three little children.

In moments, the men of our neighborhood, hearing the commotion, rushed out into the street, immediately defending my father, and chasing the assailants away. They called an ambulance and the police, and they stayed with us while my mother accompanied my father to the hospital.

While that night was a traumatic experience for us as children, it was never lost on us that our neighbors came to our immediate defense. I often wonder, in today’s world, whether others seeing a fight between white men and a black man would immediately jump to the defense of the black man. It happened in Squirrel Hill, and in 1968.

I don’t claim, however, that Squirrel Hill is the only place in America that this would happen. In fact, I have proof that it is not. Four years before this incident happened to my father, three “Freedom Summer” civil rights workers, Andrew Goodman, Mickey Schwerner, and James Chaney, were murdered in Philadelphia, Mississippi. Two of the three, Andrew Goodman and Mickey Schwerner, were Jews. They were not fighting for their own right to vote. They were fighting for mine.

They gave their lives for me.

Although June 21, 1964, was a Sunday, not a Saturday, it will always be a “Shabbos”—or holy day—a holy day—to me.

Any day can be a Shabbos, and every Shabbos is a special day.

I think that all of these heroic men, both the ones in Squirrel Hill who came to my father’s rescue, and the ones who died in Philadelphia, Mississippi, understood the third lesson I learned growing up in Squirrel Hill, namely, that:

Kosher salt is salt.

Salt must be one of the most fascinating compounds ever. It is a very simple compound—NaCl—but it is essential for human existence. It was so valuable that it was once used for money; our word “sale” comes from the Latin word for salt. But it also has much more than practical power. It was Ghandi’s march to the sea for salt that threw off the yoke of British rule in India. Indeed, Dr. King’s philosophy of nonviolent social change has its origins in Mahatma Ghandi’s nonviolent, but symbolic, march to the sea for salt.

But salt is also interesting because of the way it is perceived. All salt, after all, is just NaCl—sodium chloride. But Morton’s is celebrated in marketing circles as iconic for getting people to perceive their salt—Morton salt—as somehow “different”—more pure, better tasting, healthier—than any other brand of salt.

What makes kosher salt different from all other salt is not chemical. It’s spiritual. This is something I didn’t understand until we were out of salt and had to try what was available. And anyone who has tried kosher salt comes to the realization that kosher salt—is salt.

Its true that kosher salt has religious significance, and that difference is important for those who are observant. But for those of us who are not observant, we come to realize that, despite the religious significance, at its core, all salt—even kosher salt—is salt.

Despite our differences—our religious differences, our racial differences, our political differences—at our core, all of us share the same essence. We are, at core, all the same.

In fact, for the best people, those who “preserve” our communities—people like Mrs. Goldbach—we refer to them as “the salt of the earth.”

Conclusion

Actually, my wife Angie reminds me so much of Mrs. Goldbach in many ways. She takes the same view of community, and sees the unfamiliar as an opportunity for a new experience. And she impresses the importance of this on our kids every day.

As Christians, we say a prayer with our kids every morning before we send them out into the world. We pray for them, and for all of the people they will encounter during the day. We do this each and every day.

My wife often often tells our sons that “it is very important to believe in miracles, and that it is very important that we pray for miracles. But it is also just as important to recognize that sometimes God wants us to be a miracle for someone else.” She tells our boys, “Be someone’s miracle today.”

Wouldn’t it be a miracle—a wonderful miracle—if we had no more Fergusons, no more Eric Garners, no more attacks like the one on the magazine Charlie Hebdo in Paris, no more Holocausts—no more Shoah?

I believe it can happen. But as important as I believe it is to pray for this miracle, I also believe that it is just as important to recognize our role in making miracles like this happen. Not just for ourselves, but also for our communities, as broadly defined as we can make them.

Let us each be someone’s miracle today. Thank you.

***

To read more Tablet coverage of the Pittsburgh massacre, click here.

G. Marcus Cole is William F. Baxter-Visa International Professor of Law at Stanford University.