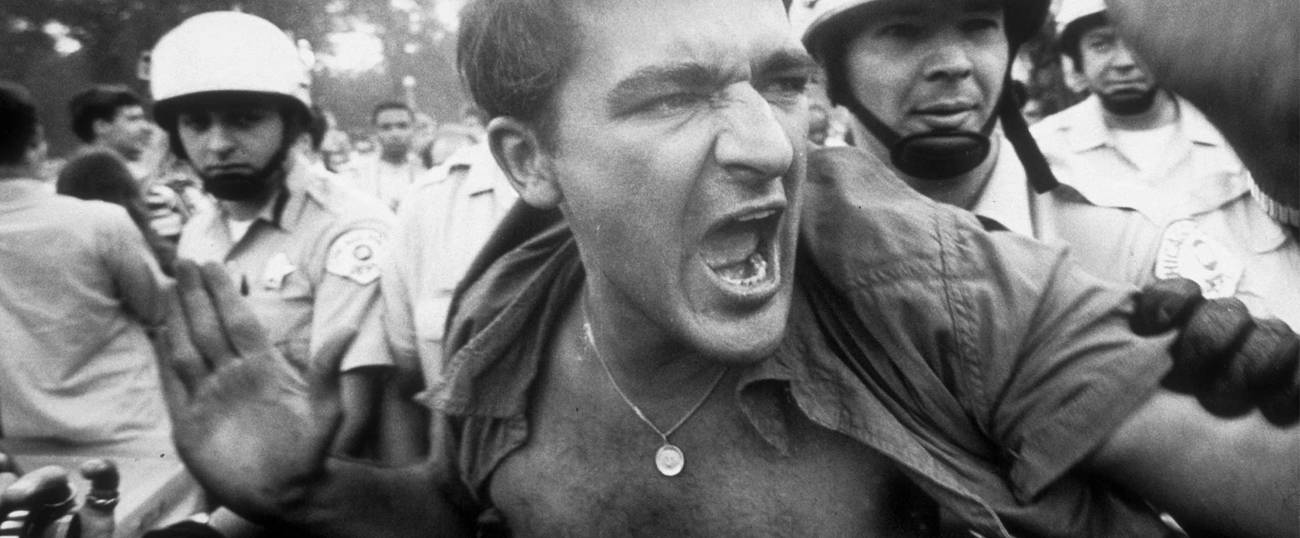

The Battle of Chicago, 1968

Fifty years after the political upheaval around the Democratic National Convention that changed America, a former editor from ‘Ramparts’ magazine sees worrying echoes today

In the late summer of 1968 the sense of anticipation was palpable at Ramparts magazine’s offices in San Francisco. The Democratic National Convention was about to convene in Chicago and we planned to be there bearing witness to the battle between the ruling war party and the brigades of youthful protesters we thought might still save our battered and bloodied country.

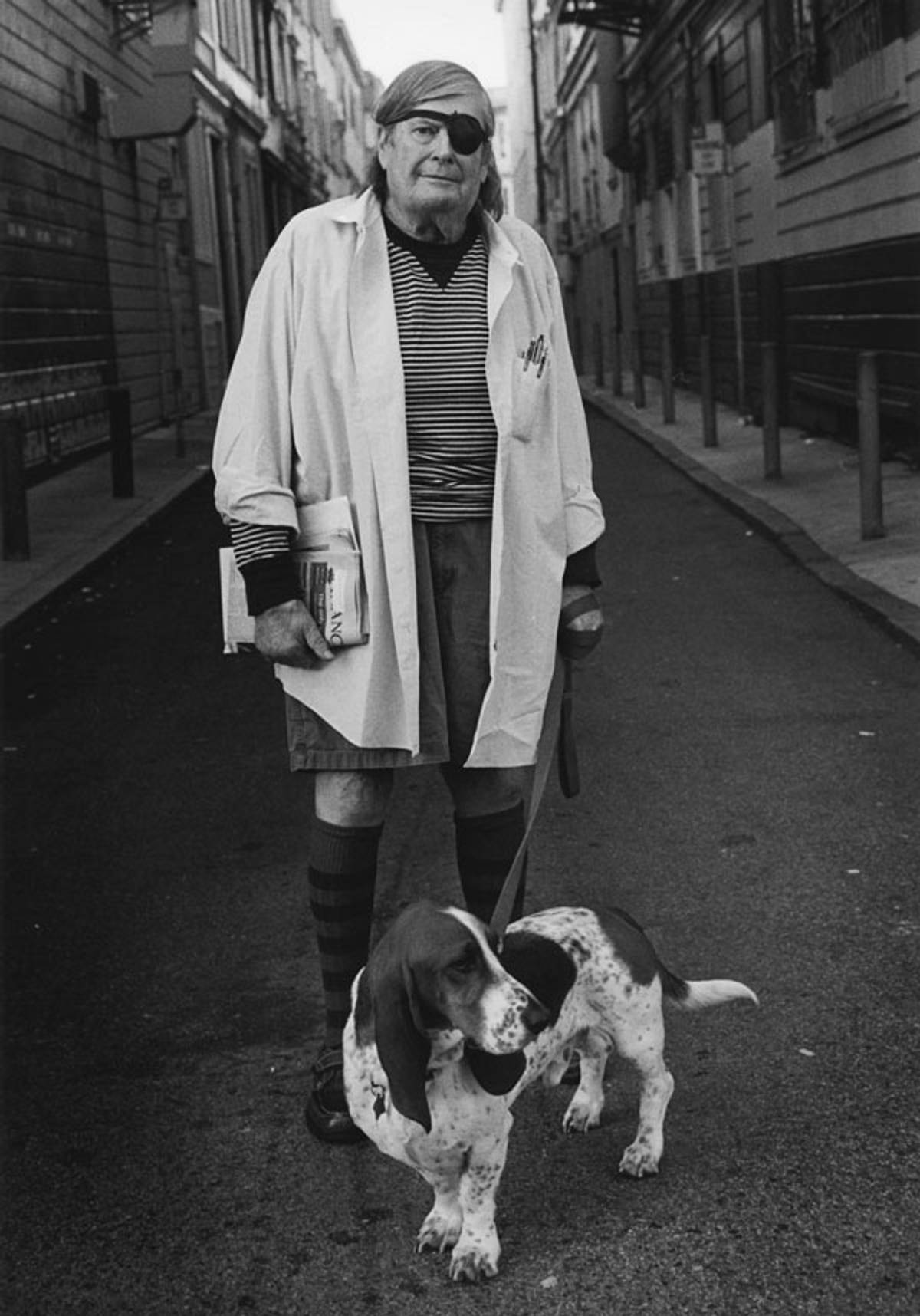

Like the protesters, the Ramparts crew was young in age and spirit. Warren Hinckle III, the hard-driving, hard-drinking genius behind many of the magazine’s exposés and political stunts, hadn’t yet turned 30. A third-generation San Franciscan from a middle-class, Catholic family, Hinckle honed his brash journalist’s skills during a two-year stint as a city reporter for the San Francisco Chronicle. He dressed like a dandy yet enjoyed drinking in dowdy looking bars favored by the city’s cops. He was no intellectual and disdained all political ideologies, but he could see where the 1960s counterculture was headed. After Hinckle gained control of what was launched in 1962 as a staid, liberal Catholic quarterly, he began recruiting writers and editors from among a cadre of radical Berkeley graduate students. I was one of those grad school dropouts.

As I’ve relayed in City Journal and elsewhere, Hinckle transformed Ramparts into a slick, four-color monthly, and it soared meteorically in the publishing world. The magazine’s paid circulation reached 250,000, unheard-of numbers for a self-proclaimed leftist journal. Even Time, our fiercest critic amongst the mainstream media, conceded that the “commie influenced” Ramparts editors managed to deliver “a bomb in every issue.”

Our biggest bombshell was a February 1967 exposé of the secret relationship between the CIA and the U.S. National Student Association. For that scoop Ramparts won the prestigious George Polk award for investigative journalism. It also led to a front-page feature in The New York Times titled “Ramparts: Gadfly to the Establishment.” The celebratory profile was topped by a picture of Hinckle, managing editor Robert Scheer and myself (I was the lead writer on the CIA article) conferring in our San Francisco office. The caption on the photograph: “Planning the Next Exposé.”

Yet Ramparts wasn’t content to merely expose government malfeasance in the venerable American tradition of muckraking journalism. We also viewed the magazine as an integral part of the anti-war “resistance.” The ’60s had engendered the “new journalism,” also known as “advocacy journalism.” Departing from the straitjacket of a fake standard of objectivity, journalists were now inserting themselves and their own point of view into their stories with such compelling narratives as Armies of the Night, Norman Mailer’s account of the October 1967 anti-war march on the Pentagon. Ramparts pushed the advocacy part into uncharted territory.

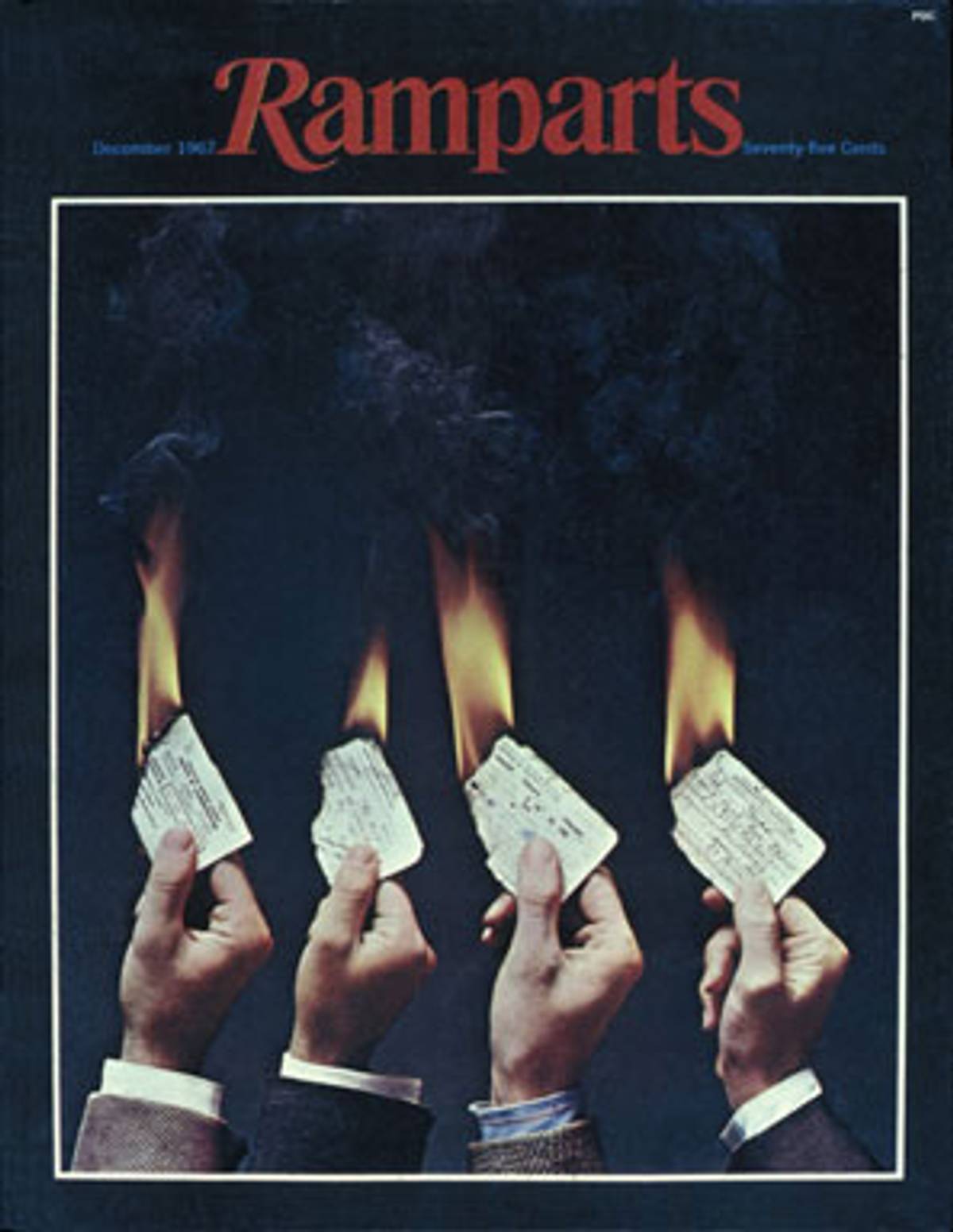

After the massive Pentagon demonstration, the editors were brainstorming about how we might dramatize our opposition to the war. I made a suggestion: The editors and writers (as many as wished to join in) should publically burn their draft cards in solidarity with the thousands of young people who were risking jail time by torching their own cards, a crime then punishable by five years in prison under the Selective Service Act.

Hinckle liked the idea, but gave it his own unique twist. Instead of another public protest, the four top editors on the masthead (Hinckle, Scheer, myself, and art director Dugald Stermer) would deliver our draft cards to renowned New York studio photographer Carl Fischer for a staged photo shoot. Fischer framed a picture of four upright hands (actually four hand models) holding our burning draft cards with our names still clearly visible. Shot against a black backdrop with no additional text, the photo became the cover of Ramparts’ December 1967 issue (at right). In another inspired PR stunt, Hinckle then purchased advertising space from the New York City Transit Authority and ran the draft card cover on the sides of city buses plying the streets of Manhattan.

As might have been expected, the government took the bait. The Department of Justice subpoenaed the editors to appear before a federal grand jury in Manhattan. The four of us flew into Gotham from San Francisco, courtesy of the feds, and checked into the Algonquin, our favorite New York hotel. Against our attorney’s advice we then leaked the story of the subpoenas to Sidney Zion, a legal reporter at The New York Times. Zion’s exclusive front-page story raised the specter that applying the criminal provisions of the Selective Service law to editors making a political statement in their own publication would erode First Amendment protections for all journalists.

The next day we appeared before a federal grand jury at the Foley Square courthouse in lower Manhattan, but refused to answer the U.S. attorney’s questions. The government then backed off, probably because the Times had called attention to the free-press issue. Having been anointed as First Amendment heroes by the “paper of record” we laughed all the way back to San Francisco on our government-paid flight. The draft card cover was one of the magazine’s best-selling issues.

***

As the national protests grew in numbers and audacity, Ramparts deepened its direct involvement with the “resistance.” In September 1967 the magazine was invited to a conference in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, bringing together a broad coalition of U.S. anti-war activists and officials of the North Vietnamese government and the South Vietnamese National Liberation Front–i.e., the Vietcong.

I was designated as the Ramparts representative to the Bratislava meeting. The friendly get-together on the banks of the Danube was the brainchild of Tom Hayden, one of the founders of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the nation’s leading radical student organization. In Bratislava he pushed the American delegation to sign on to a statement endorsing military victory for the Vietcong.

I forcefully objected, arguing that Hayden’s proposal would needlessly alienate many patriotic Americans who were coming around to support peace negotiations leading to a U.S. withdrawal. After all, wasn’t getting our troops home the only sensible objective for the peace movement?

Apparently not. On the conference’s last day Hayden delivered a passionate speech calling for a Vietnam liberated and unified by the Communists. He ended his address by proclaiming that the anti-war movement had a moral obligation to confront the U.S. government, announcing “we are all Vietcong now.”

Back in the United States, Hayden continued to spread the gospel of a Vietcong victory. He made that position even more concrete by urging protesters to “bring the war home”—i.e., through disruption and violence in the streets. Hayden perceived that the 1968 Democratic Party Convention in Chicago, scheduled for the last week in August, would provide a unique opportunity to do just that, to bring “war” and chaos to the streets of a major American city. Ramparts indulged Hayden’s fantasies. In an article in the July 1968 issue he called on the shock troops of the resistance to come to Chicago to show their mettle and “catch up with the worldwide feeling that the Vietcong are the heroes of this war.”

In Chicago, Hayden and veteran peace-movement organizer David Dellinger became official spokesmen of the protest group called the “Mobe,” representing a broad coalition of U.S. anti-war groups. Meanwhile America’s two leading counterculture agitators, Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman, toured the country recruiting an eclectic collection of hippies, beatniks, druggies and rock ’n’ roll freaks to come to Chicago to celebrate the people’s “Festival of Life”—with music, dancing, and drugs—in opposition to the “culture of death” represented by the ruling Democratic Party. The two provocateurs created a fake entity called the Youth International Party (YIP) and their followers became known as “Yippies.” But it wouldn’t be all countercultural fun and games in the Windy City. In a pre-convention speech Rubin echoed Hayden: “We are now in the business of wholesale disruption and widespread resistance and dislocation of American society.”

Like Eisenhower and Montgomery at Normandy, the commanders of the two “anti-war” armies divided the ground for the expected assault on the city by tens of thousands (hopefully more than 100,000) of young protesters. Hayden and Dellinger staked out Grant Park across Michigan Avenue from the massive Conrad Hilton Hotel, which served as convention headquarters and where many state delegations were housed. Meanwhile the Yippies set up their own encampment in bucolic Lincoln Park two miles farther north along the lakefront. The plan was for the two contingents to periodically surge on to the streets from their base camps for the planned street demonstrations.

The battle of Chicago thus looked like a familiar playing field to the Ramparts’ reporters. Yet there were also a couple of complicating factors that threatened the success of our enterprise. For one thing the magazine was now running on fumes. Hinckle had never met a budget he didn’t immediately discard. There had been too many booze-filled lunches at some of San Francisco’s finest restaurants. When writers had to be in New York they were booked into the pricey Algonquin Hotel because Hinckle liked the link with the legendary New Yorker Round Table. Creative with words and headlines, he was shockingly careless with other people’s money. By the summer of 1968 he had managed to burn through 2 million dollars from several politically sympathetic investors.

Chicago represented yet another journalistic challenge. We found ourselves in the middle of the most heavily covered news event in recent history. Over 3,000 credentialed reporters and photographers had descended on the city (one for every two convention delegates) in search of the big story.

Almost every quality magazine in the country sent their own A-list writers, including a few best-selling novelists, to Chicago to offer their deep thoughts about the week’s events. Here’s just a partial list of the literary all-stars who showed up for the convention: Norman Mailer was there for Harper’s; Esquire countered with Jean Genet, Terry Southern, and William Burroughs; The New York Review of Books dispatched William Styron and Elizabeth Hardwick; The New Yorker was represented by Renata Adler. Most of their stories would be out before Ramparts could manage to get its next monthly edition printed and into the hands of subscribers. That didn’t augur well for a fresh Ramparts bombshell.

Hinckle didn’t care that the cupboard was bare, nor did he seem worried by the literary competition. The Ramparts crew arrived in Chicago as if it would be all wine and roses again, with no bills ever coming due. Hinckle booked 10 rooms for the staff, plus a suite for himself, at the swanky Ambassador Hotel near Lincoln Park. Among the hotel’s attractions was that it was the site of the notoriously decadent Pump Room, Chicago’s leading celebrity nightspot and restaurant. On any given evening you might find the likes of Frank Sinatra, Paul Newman, Jane Fonda, Elizabeth Taylor, or Truman Capote—and sometimes even His Honor, Mayor Daley—dining at one of the plush leather booths that circled the room.

During our week in Chicago the staff did manage to pull off one more journalistic coup—a daily Ramparts Wall Poster to provide running commentary on the protest movements and the latest political gossip from within the convention. The Wall Poster was designed as a single folio sheet reminiscent of the street posters produced by Chairman Mao’s Red Guards. The motto on top of the front page was “Up Against the Wall,” a riff on the black power slogan, “Up Against the Wall, Motherfucker!”

The Wall Poster was posted on very few walls, but was distributed inside the protest encampments and given out to convention delegates. The first issue carried a welcoming message from Tom Hayden. We have come to Chicago to smash the warfare state, Hayden declared, and the street protests in the city would reveal “American reality stripped to its essentials—a confrontation between a police state and a people’s movement.”

On day three of the convention the Wall Poster’s featured article was somewhat different in tone. “Tear Gas in the Pump Room!” screamed the top of the Wall Poster in mock outrage. It was perhaps Hinckle’s funniest headline ever. And yes, indeed, the glitterati of Chicago (and some of us Ramparts editors too) were imbibing late into the night in the Pump Room and took a dose of standard-issue tear gas as city cops clashed with Yippie demonstrators on the streets near the hotel. Hayden and his fellow activists didn’t appreciate Hinkle’s sense of irony.

***

After spending six days and nights in hurly-burly Chicago with out-of-control cops, stoned Yippies celebrating their “Festival of Life,” Vietcong-flag-waving young revolutionaries throwing rocks and other missiles, and the always quotable Mayor Daley spewing anti-Semitic profanities, the Ramparts staff checked out of the Ambassador and headed to New York. There, in Hinckle’s suite at the more subdued Algonquin Hotel, we ground out our promised 20,000 words on the meaning of it all.

By the time we finished our report and then rushed the convention issue to the printer, yet another month had passed. Chicago ’68 was already stale news. Ramparts’ collectively written essay included a few more grisly details about the brutality of the Chicago police and the oppressive atmosphere inside the convention hall. But by now there was nothing controversial about such truths. Indeed, a federal commission would soon conclude that Mayor Daley had encouraged a “police riot.”

We missed a golden opportunity to provide a more complicated yet historically accurate account.

Apart from submitting a few memos on the clashes I witnessed on the streets, I had little input into the Ramparts essay, perhaps because I was now even more skeptical of Hayden’s “bring the war home” strategy. Unfortunately the other editors were moonstruck with the vision of young radical combatants taking over the streets. The essay contained this syrupy description, so uncharacteristic of our usually hardboiled writers, of one of the protest marches: “The demonstrators were first of all a community, in a sense of that word that has been lost to most older Americans—a group united in the joy of being together and in the astonishing liberation of the discovery that the streets are truly, and not in a merely rhetorical sense, theirs.” On Chicago’s streets, according to Ramparts, “one era was ending and another was announcing itself.”

To be sure, Ramparts produced an emotionally satisfying narrative about a criminal war, righteous young protesters, and brutal Chicago cops. But we missed a golden opportunity to provide a more complicated yet historically accurate account. We didn’t dare publish the one story we owned exclusively—how Tom Hayden and a small group of pro-communist (i.e., pro-Vietnamese Communist) activists, had cynically planned a violent confrontation in Chicago in order to open another front in the war and to aid the Vietcong. The slogan “bring the war home” had become a destructive revolutionary fantasy and we should have called it by its name. Ramparts thus failed the test of true journalism, even the “new” journalism.

The editors chose to ignore another inconvenient truth: Hayden and Rubin failed dismally to deliver on their promise of bringing tens of thousands of protesters to Chicago. Such a large turnout initially might have seemed a reasonable expectation. After all, more than 100,000 anti-war protesters had shown up for the Pentagon demonstration a year earlier. However, as the protest leaders ratcheted up their bravado about “bringing the war home” they also managed to scare off thousands of moderate anti-war protesters. Presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy, the political hero of the anti-war movement, finally felt compelled to warn his followers to stay away from the convention because of the thinly veiled threats of violence coming from Hayden and Rubin.

The 10,000 young people who did take to Chicago’s streets were confronted by 8,000 city cops working 12-hour shifts, thousands of bayonet-wielding National Guardsmen, and another 1,000 federal undercover agents circulating within the demonstrators’ ranks. With such overwhelming force the demonstrations could have been contained with far less violence, also resulting in fewer ugly headlines. But the gratuitous brutality of Daley’s cops allowed Ramparts and many in the liberal media to plausibly spin the narrative of an American police state.

Despite the despicable behavior of Mayor Daley and his enforcers, the American people didn’t care much for the protesters either. The highly regarded Survey Research Center found that only 10 percent of Americans believed the police used too much force, while 25 percent thought not enough force was used. Amazingly, only 12 percent of those opposed to the war expressed sympathy for the Chicago protesters.

Partly in reaction to the disruption and violence in Chicago, Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon jumped to a 15-point lead over the Democratic nominee, Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Nixon went on to win the election by a mere 500,000 votes. Many analysts believed that the Chicago riots were a factor in Nixon’s narrow victory.

Ramparts didn’t see, or didn’t care to see, that Tom Hayden’s dream of “bringing the war home” actually undermined the goal that all of us in the peace movement shared—ending the real war in Asia and bringing the troops home. In the final weeks of the presidential election the Johnson administration pushed for a negotiated end to the conflict, an initiative that Nixon managed to undermine because it would have boosted Humphrey’s chances. The new president then extended the senseless war for another seven years, resulting in an additional 22,000 dead Americans and hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese victims, including civilians.

The only era that ended in Chicago was the era of Ramparts. A few months after the convention the magazine filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. Having been insulated from the consequences of his financial recklessness, Warren Hinckle resigned and, with Sidney Zion, launched a new muckraking magazine called Scanlan’s. The co-editors raised almost a million dollars from investors and then folded the magazine after publishing nine issues.

The miracle of the capitalist system’s bankruptcy laws allowed anti-capitalist Ramparts to go on publishing its monthly issues—but this time under court-ordered financial oversight. Salaries were cut, staffers were laid off, and there would be no more fancy staff lunches. After an internal power struggle David Horowitz and Peter Collier, two of the original group of radical Berkeley graduate students recruited by Hinckle and Scheer, took control of the magazine. They moved Ramparts across the bay to Berkeley where the rents were lower and they would be closer to their radical roots.

Ramparts now made common cause with the most unhinged elements of the revolutionary left. Under Collier and Horowitz the magazine published Tom Hayden’s broadsides calling on radical students to “smash the state,” while also promoting the gun-toting Black Panthers as “America’s Vietcong.” Ramparts reached an all-time low with its cover showing a burning Bank of America branch in Southern California with a text declaring that the students who firebombed the building “may have done more for saving the environment than all the teach-ins combined.”

***

In 1975 I was living and reporting in Israel when I read an item announcing that Ramparts had finally shut its doors. Though my first venture in professional journalism had taken me on an often exhilarating adventure tour, I didn’t shed too many tears for the demise of my old magazine. By then I had left my youthful radicalism far behind and was beginning a long journey towards a moderate, sane conservatism. I eventually became a senior fellow at Manhattan Institute and a frequent writer for the institute’s magazine, City Journal.

Over the past two decades I occasionally wrote about how contemporary American progressivism seemed not to have learned any of the lessons from the implosion of ’60s radicalism. Indeed I marveled at how the left seemed even more deplorable now with the drift toward identity politics and its contempt for free speech and intellectual diversity.

Until the emergence of Donald Trump and Trumpism, I would never have believed that the conservative movement might be infected by similar pathologies. I then experienced a kind of political vertigo as conservative intellectuals, including some of my colleagues and friends, began speaking in the language of none other than Tom Hayden. Both before and after Trump’s election, writers I had respected now seemed to delight in the prospect of “smashing” the state (though of course they called it the “deep state”). Some even thrilled vicariously over Trump rallies where mobs called for “locking up” a political opponent or screaming hateful obscenities at journalists they didn’t like, just as the leftist mobs of the ’60s called for jailing the U.S. warlords or “offing” the pigs.

The similarities between then and now, between the ’60s radicalism and the current Trump fever became too obvious to ignore. During the 2016 election my friend Ronald Radosh reported that Steve Bannon, Donald Trump’s campaign manager and chief strategist, referred to himself as a “Leninist” while explaining to Radosh why he wanted to bring down the globalist ruling class responsible for so many disastrous wars. It has since occurred to me that Bannon’s statement to Radosh that he wanted to “bring everything crashing down, and destroy all of today’s establishment” was more “Haydenist” than “Leninist.” After all, Tom Hayden was talking about smashing the state 50 years ago in liberal America rather than 100 years ago in imperial Russia.

At City Journal I was part of a writer’s community valuing ideas, debate, and civility. One of our intellectual heroes was the anti-totalitarian thinker, champion of classical liberalism and fierce opponent of populism, Friedrich Hayek. I was thus shocked that my colleagues weren’t willing to speak out against the new right-wing populism exemplified by Bannon and Trump. When City Journal then made it clear that I wouldn’t be allowed to write anything critical about President Trump or these deplorable developments in the conservative intellectual world, I resigned in protest. It was almost a half century since I had drifted away from Ramparts because I wouldn’t be allowed to write critically about Tom Hayden’s agenda for America.

Our country survived the political fevers brought on by the mindless radicalism of the 1960s. As a never-Trump conservative I’m much less confident about America’s ability to survive the assault on truth and liberal values now coming from both directions, the left and the right.

Sol Stern is a former fellow of the Manhattan Institute and has written for many publications, including City Journal, Commentary, The Daily Beast and the Wall Street Journal.