The Borg of the Gargoyles

How government, tech, finance, and law enforcement converged into an all-knowing criminalization complex—and how to resist it

In Neal Stephenson’s 1992 novel Snow Crash, the Central Intelligence Corporation—the result of a merger between the Library of Congress and the CIA—employs a number of people who remain continuously connected to the Metaverse. These grotesque characters, who Stephenson calls “gargoyles,” wear computer components on their heads and bodies and serve as “human surveillance devices, recording everything that happens around them,” passively but perpetually dragnetting data and intelligence on human beings, their movements, and their interactions with the surrounding physical environment.

On July 7, 2014, Popular Science reported on “scan artists”—repo men whose tow trucks are “customized with tens of thousands of dollars’ worth of cameras and image processors and can scan [license] plates even while tearing down a highway.” These scan artists feed massive centralized databases with plate scans, historical coordinates, and drivers’ personal details, which private companies use to build predictive models of the whereabouts of vehicles targeted by banks for repossession. The scan artists, of course, are not limited to surveillance of cars already in default. They are not even limited to cars—or to car owners, or to debtors, or to deadbeats. They are gargoyles, vacuuming up all the data that people generate by participating in the internet and by moving in the physical world.

The Popular Science report became a favorite among Stephenson fans, tech lords, and presumably law enforcement. But otherwise the story made little impact, casting no greater imprint on the public consciousness than contemporaneous reports that Chinese state-sponsored hackers breached the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), obtaining over 22 million records on U.S. government employees and contractors, their families, and their friends.

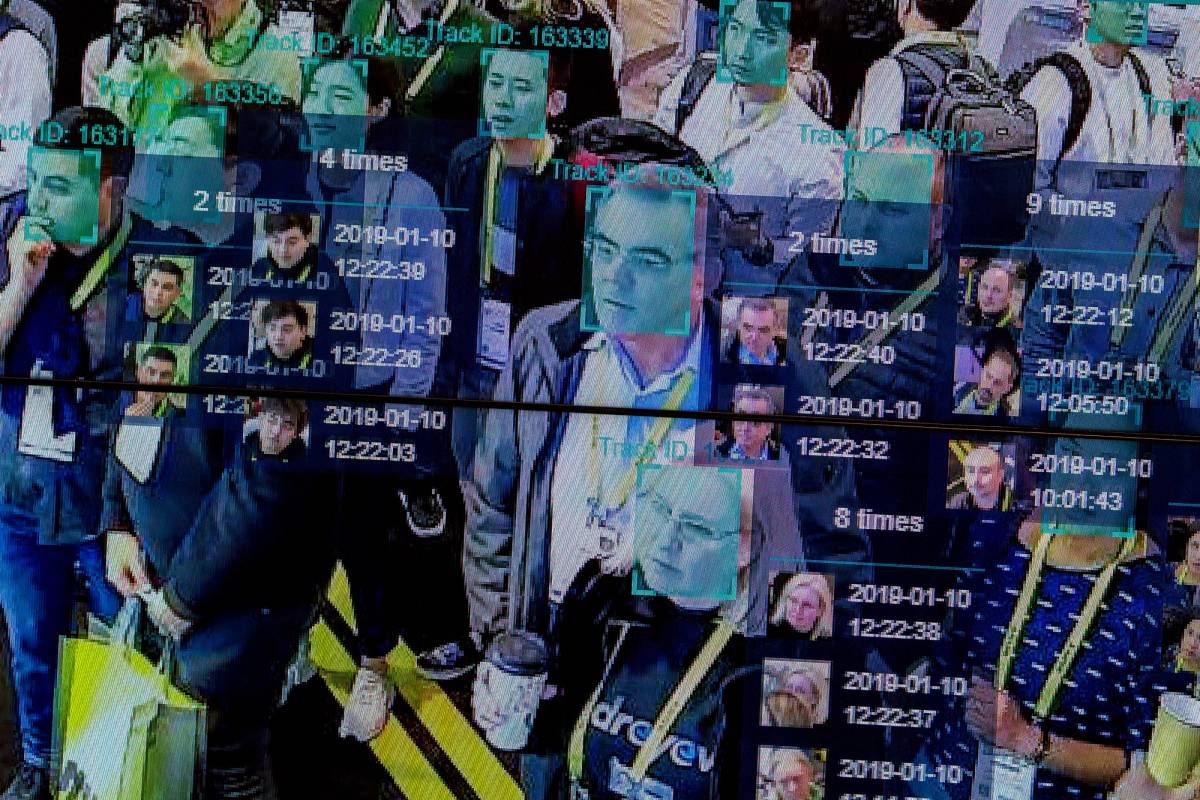

In the years since, however, gargoyles have become more ubiquitous—and more grotesque. Consider the last couple months alone. On May 11, Vice reported that the San Francisco Police Department has been using driverless cars—assumed by onlookers to be harmless beta tests from Silicon Valley tech companies—as mobile surveillance cameras to “[record] their surroundings continuously and have the potential to help with investigative leads.” On June 1, a joint investigation by provincial privacy commissions in Canada found that TDL Group Corp., which operates the Tim Hortons fast food chain, used location data to infer where customers “lived, worked, and whether they were travelling” and “generated an ‘event’ every time users entered and left their homes, entered and exited their office, or travelled.” On June 29, Politico reported that Canada’s national police admitted to using “spyware to infiltrate mobile devices and collect data, including by remotely turning on the camera and microphone of a suspect’s phone or laptop.” Last week, the European Union proposed a regulation allowing “artificial intelligence with subsequent review conducted by a human” to scan private messages for evidence of “grooming.” Yesterday, the American Civil Liberties Union published records detailing how the Department of Homeland Security purchases the cellphone location information of U.S. citizens from private data brokers.

In the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, most of America’s biggest tech and social media companies have so far declined to clarify whether they would comply with law enforcement requests for data related to investigations involving citizens seeking or providing abortions in states that ban them. Regardless of the decisions of individual corporations, we can be certain of two things: No. 1, Americans who seek or provide abortions in states where it is illegal will unwittingly generate mountains of data documenting their newfound criminality; No. 2, that data will be dragnetted by gargoyles and maintained by private companies with government contracts.

Even the most radically liberal thinkers of our past couldn’t have imagined the totality of rights that the Borg is eliminating simultaneously.

Now that “location awareness” is customary in mobile phone apps, which also record private conversations between users and their family, friends, and lovers, a degree of intrusion into the private lives of human beings never thought possible is happening on a minute-to-minute basis. Every day, gargoyles are collecting information on our speech, movements, and purchases; every second, our mobile phones are exfiltrating data from our private lives to corporations, local police, and federal law enforcement, as well as foreign intelligence services.

If there was ever a point at which we could plausibly regard this reality as trivial, that point has been crossed. During the Ottawa trucker protests in February, Canadian authorities demonstrated how easily modern governments—including democracies with robust rule of law—can use the digital financial and payments system to freeze the bank accounts and seize, block, or escrow the funds of citizens without even obtaining convictions. At the end of March, Google announced that Google Docs will soon start flagging “potentially discriminatory or inappropriate language” and providing “suggestions on how to make your writing more inclusive and appropriate.” Google later paused the rollout of this feature, presumably in response to popular backlash. But it’s not hard to see how the two developments could conceivably be linked in the near future: The ability of governments to wield the financial system as a weapon of enforcement against private language and opinions judged to be politically undesirable.

The consolidation of government, tech, finance, and law enforcement into a Borg-like hive mind that continually collects data on our private lives—allowing it to criminalize, de-bank, and de-platform any citizen at will, without any pretense of due process—has emerged as an imminent civilizational threat. Even the most radically liberal thinkers of our past couldn’t have imagined the totality of rights that the Borg is eliminating simultaneously—rights so obvious and intrinsic to human life that no one ever thought to codify them. A star-crossed couple in 1950 kept apart by their families, communities, or police due to race or sexuality could still—even if only in secret—speak in private, exchange letters, keep diaries, and if they took special care, meet in person to consummate their love.

Today, no matter what protections they still nominally enjoy under the Bill of Rights, Americans trapped in the modern equivalent of such circumstances would have their messages instantaneously siphoned, their conversations recorded, their diaries digitally copied, their trysts interdicted. Their lives and fate would be held hostage—as all of us now are, whether we’ve fully realized it yet or not—by the Borg.

The first thing to understand about the Borg that the gargoyles made for us is that it’s a product of evolution, not intelligent design. There was no conference of rootless cosmopolitans who descended on a chalet in the Alps to plot the destruction of the Constitution and turn the United States into Communist China. The Borg is simply what happens when a technologically advanced society is driven by default toward the naturally expansionist aims and incentives of government and law enforcement.

The U.S. government is able to chase categories of speech and pockets of currency it doesn’t yet control because anyone the state would like to be deemed a criminal can easily be deemed a criminal. As the body of state and federal laws has accumulated over the last 100-plus years, it has become possible to find some law, any law, that any individual citizen has broken or is currently breaking. This allows the state to go after anyone it wants at any moment through prosecutorial overcharging; more than 95% of criminal convictions in the United States today are obtained through plea bargaining rather than jury trials, all but eliminating citizen participation in the justice system. (A surprising number of public figures who are well-known in the popular imagination for committing serious crimes were, in the absence of actual evidence of criminal activity, only ever charged with the spurious crime of “lying to a federal officer.”) The most significant consequence of overlegalization, therefore, is not inefficiency, risk aversion, or higher costs. It is the mass criminalization of an entire society. Technological advances have simply provided new tools for criminalizing and punishing U.S. citizens who, against all odds, still appear to maintain a heroic belief in due process and the right of appeal.

After the terror attacks of 9/11, the global war on terror provided a broadly popular justification for granting the Departments of Justice, Treasury, and other executive agencies with ever-more advanced and intrusive surveillance capabilities to pursue such ends. In the first decade after the twin towers fell, Americans got used to the idea of vastly expanded domestic surveillance (the Patriot Act), U.S. government coercion of foreign entities to report assets held by Americans (the Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act), and the fact that the president of the United States maintains a “kill list” of human beings—including U.S. citizens—not formally charged with any crime but who are chosen by metadata for targeted assassination.

Even many seemingly benign efforts to, for example, crack down on criminal money-laundering or tighten U.S. sanctions, are in fact extensions of this now deeply entrenched and extra-Constitutional process. Under both the Trump and Biden administrations, the Treasury Department has advocated for adding a “know-your-customer” legal proviso requiring any crypto wallet belonging to a U.S. citizen to carry identity markers, like a Social Security number or commercial debit account. The whole point of crypto wallets, needless to say, is that they can be held anonymously. The Biden administration’s recent announcement that it is making progress on implementing these rules, first proposed in 2020 by the Treasury Department’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN), was thus a warning that any owner of a crypto wallet who wishes to remain anonymous will soon be deemed a criminal.

Yet such relatively low-tech, often clumsy public sector efforts—driven predominately by lawyers, cops, civil servants, and politicians—do not by themselves constitute a juggernaut against which resistance is futile. It is their convergence with technology companies, which often contract with the U.S. government, that pushes the Borg toward its ultimate evolutionary goal of achieving perfection.

Because major data collectors and brokers like LexisNexis are private corporations, it is perfectly legal for them to dragnet information generated by internet users and their movements in the physical world and use it to construct massive surveillance databases. It would be unconstitutional for the government to do this work itself, but nothing stops it from purchasing these databases as a customer of the companies. When hackers breached OPM in 2014-15, SolarWinds in 2020, and, on more than one occasion, Aadhaar (an Indian government database containing the private biometric information of more than 1 billion Indian citizens), what they revealed was qualitatively different from Edward Snowden’s famous revelations of an NSA-based super-surveillance system: They demonstrated an unbroken chain of entirely legal contracts in which private companies siphon off citizen surveillance data and merge it with the government’s own data banks.

One practical manifestation of this high-low tech, public-private convergence is geofencing. Because we all carry personal surveillance devices—known as Samsung Galaxies or iPhones—in our pockets, a relatively easy way for the Borg to curtail certain First Amendment freedoms is for the U.S. government to designate a geofenced area, require Apple and Google to divulge all the phones active in that grid square, ban rideshare apps from entering it, and oblige commercial banks and digital payments companies to de-bank anyone who breaches it. With some laudable exceptions, most companies don’t have to be “forced” into such compliance—they know that everything from industry regulation to immigration policy, tariffs, and access to the Chinese market depends on their cooperation. After the experience of COVID lockdowns, Black Lives Matter protests, the Jan. 6 Capitol riots, and the trucker convoys, effective geofencing that not only surveils people but limits their freedom of assembly by herding and controlling their movements should no longer code as science fiction.

Nor should the most distinctive feature of the Borg itself: Whether you’re geofenced out of a public area, de-platformed by a faceless computer algorithm, de-banked by a faceless government bureaucracy, or criminalized by a faceless law enforcement agency, there’s never a real person or group of people who you can hold accountable.

Smothering but vulnerable technology wielded by a prosecutorial state that imposes a maddening diffusion of accountability: Wasn’t the hedge against this dystopian future supposed to be crypto? Wasn’t the whole point of the blockchain that it couldn’t be regulated by government, that no corporation could capture the data generated there, that no banks or financial intermediaries are involved, and that no state authority can tamper with it, allowing us all to build a better future? Well, not exactly. Hardcore crypto evangelists continue to believe that a sovereign, cloud-based blockchain system will provide such a superior mode of transaction and governance that we will all live crypto-only lives and starve out the Borg. Maybe we will. But crypto has always been grounded in at least two more realistic promises, both of which should give us hope that resistance is not, in fact, futile.

The first is simply that crypto allows the unbanked to bank. In the United States, checking accounts function as a version of debt, and thus require credit worthiness—which is why over 6% of U.S. households (around 14 million American adults) are currently cut off from the banking system. But because of the way financial ledgers balance on crypto platforms, owners can never go below zero. That means anyone can create a crypto wallet at any time, no permission needed—including those targeted for speech or movement that the government deems impermissible. That’s what makes it impossible for the government to regulate crypto technologically, if not legally.

The second, and perhaps more significant, promise of crypto is sociological. Building from mathematical first principles, crypto keeps alive the dream of returning power to the self-sovereign individual—in control of her own data, her own finances, and her own destiny, and who can choose which segments of privacy to opt out of, rather than the other way around. This is why tracking the market value of cryptocurrencies on any given day is a mostly pointless way to gauge the significance of cryptographic technology—it’s the existence of cryptocurrencies that serves to reinforce self-sovereignty as a concept, to counterbalance and compete with a key monopoly power of the state, and to keep the ideological flame of individual freedom burning. That, and not the destruction of the Federal Reserve, is why crypto remains a viable form of resistance to the Borg.

Another important tool of resistance is end-to-end encryption (E2EE). E2EE has faced similar challenges to crypto, with repeated attempts to legally mandate built-in government backdoors. The Clipper chip, an encryption device the NSA developed to “allow Federal, State, and local law enforcement officials the ability to decode intercepted voice and data transmissions,” was introduced as early as 1993. The Clipper chip died a predictable death only three years later, but to this day the U.S. government—which cannot secure its own data or protect its own employees from Russian or Chinese hacking—still demands special technological privileges, or “golden key” solutions, to E2EE (typically for reasons of “national security”).

Despite the obvious challenges, E2EE remains a practicable impediment to the natural trajectory and purpose of the Borg: unlimited visibility into our finances, speech, associations, and thoughts. The combination of crypto and E2EE, in fact, might one day allow us to use private keys in computer software to privately secure as much of our money, speech, associations, and thoughts as possible. Without it, the Borg will only continue to grow, playing a larger and larger role in the way we move, spend, speak, and think.

And what about government itself? Isn’t there a role for individual legislators who understand what the Borg is doing to the Bill of Rights—that there are few things more fundamental to being human than the ability to earn, exchange, and save your own resources, without surveillance or interference? The current crop of American legislators appears to have little interest in ringfencing these rights. But in order to claw back the basic individual freedoms that form our inheritance as human beings and as Americans, the resistance will need legislators and other political leaders willing to say no to law enforcement and to prioritize the privacy of U.S. citizens over the perverse incentives of the national security bureaucracy.

These are revolutionary times. Processing speeds and data storage capacities that were computationally impossible only 20 years ago are now trivial, cheap, and getting cheaper. Technological progress in computing power is not just advancing; the rate of advancement is accelerating, providing an increasingly fast and efficient conveyor belt of oppressive tools to the Borg.

But the technology itself is value neutral—it is neither good nor evil. A conveyor belt of tools is also available to the resistance. It is the trial of our generation to take advantage of those tools before the Borg assimilates so much of our lives that we as a society and as individuals can no longer cope. Resistance to the Borg, therefore, is unlikely to be a glorious endeavor. It probably won’t consist of flying cars, destroying the IRS, replacing the nation-state, or building sea-faring crypto colonies. At least for now, resistance begins by accepting the fact that one of the great hopes of the next technological age will simply be to help us reclaim the rights and freedoms we’ve already lost.

Jeff Garzik (@jgarzik) is the co-founder and chief designer of DeFi platform Vesper Finance and the co-founder and CEO of Bloq. He was previously a Bitcoin core developer, and his work with the Linux kernel is found in every Android phone and data center running Linux today.

Jeremy Stern is deputy editor of Tablet Magazine.