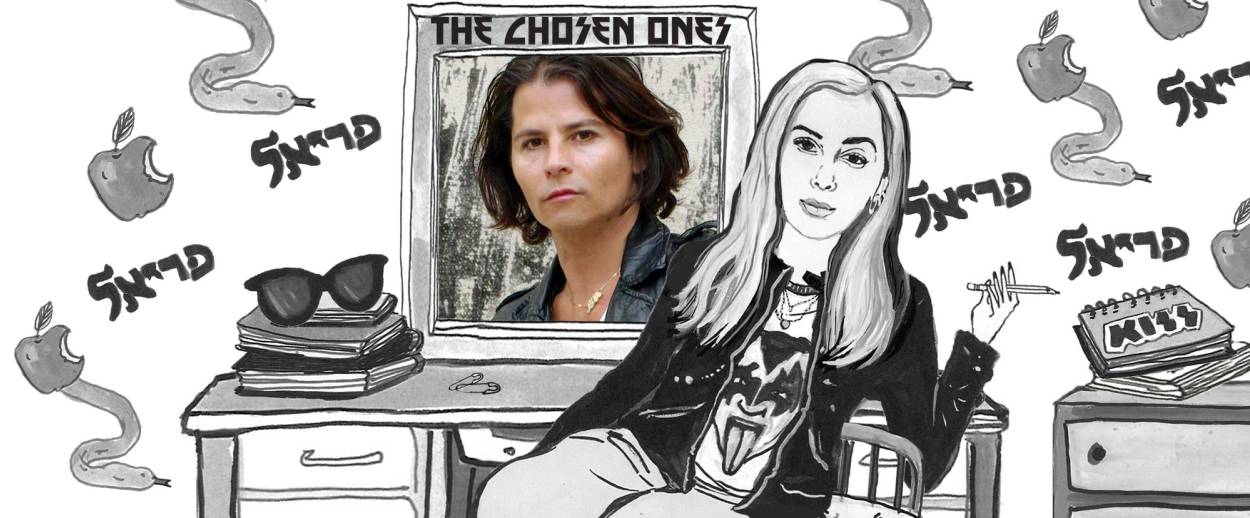

The Chosen Ones: An Interview With Nir Hod

The Israeli artist on his creative process, the importance of conflict in art, and why he’ll never eat gefilte fish and lox

If Anthony van Dyck, Rembrandt, and Andy Warhol had made wild passionate love, say, and had a baby, the result may well have been Nir Hod. The Israeli artist is as much master of his craft as he is pop, and his work—from sculpture to video to high realism painting—is tantalizing. He shows us the beauty of destruction, the allure of the forbidden, and how conflict can exist in perfect harmony. Like the snake in the Garden of Eden, Hod’s work consistently temps us with the sweet and vicious allure of the forbidden. Genius, his series of tempestuous and eerily beautiful children smoking cigarettes, is stunningly gorgeous and deeply disturbing. The same could be said for Mother, in which Hod recreates, 13 times over, the woman from the famous image of “The Boy from Warsaw“—except she looks like could be shopping at Barney’s. And that is kind of the point. For Hod, who grew up in Tel Aviv, context is everything.

In real life, we know, as the old cliché goes, actions speak louder than words. But what about in art? His work makes me wonder: Should we trust what we see, or, rather, trust what we feel? I recently caught up with him in his studio in the West Village and, after a fairly lengthy conversation, I’m still not certain of the answer. Which, again, is quite possibly the point.

Periel Aschenbrand: Can you talk to me a little about conflict?

Nir Hod: In general, my work has a lot to do with conflict and paradox. This is not just in my work, but in life in general. In art, conflict can live together so well, compared to life, where it cannot. This is why I choose art. I’ve always liked the idea of conflict. If you are a thinker or a sensitive or philosophical person, you cannot escape it. And I like to deal with it because from a very young age I understood that this is the best place to play and art is the only place where conflict can live in a beautiful way. From the visual aspect to the concept behind it.

PA: And at the same time, it’s very aesthetic, very beautiful.

NH: An aesthetic can be beautiful or ugly. And at some point it doesn’t really matter because it’s so much about context. And marketing. Something beautiful can turn into something ugly in one second. At the same time, the right word, the right explanation, the right light, can turn something ugly into something beautiful and interesting. It happens with people and it happens with landscapes and it happens with art. Why? Because we change and develop.

PA: Because we change and develop?

NH: Absolutely. And also, the value of aesthetic changes. You look at a picture of yourself 10 years ago and you say, “I can’t believe that this is what I used to wear, I can’t believe this was my haircut, I can’t believe I wore those shoes, I can’t believe this was my eyebrow!” It’s surreal. My whole point is to do a twist on the traditional and classic. By that, you kill an icon and you create a new icon.

PA: I love that. That’s so you.

NH: I choose to be the kind of artist who develops all the time—bodies of work, materials, different fields. I’m so influenced by history, art history, fashion, and architecture and it’s all about evolution—a body of work that leads me to another body of work. I’m not interested in replicating myself and my art. I may have different bodies of work, but their soul of the work and conceptually, they are the same—the impact of the surface and the seduction that leads you into the conflict of the familiar.

PA: There’s always something very seductive about your work. And your persona, too.

NH: I’m always interested in forbidden desire.

PA: How old were you when you came to the U.S. from Israel?

NH: 28.

PA: And did you grow up very Jewish?

NH: No, but I’m very spiritual. I’m a believer.

PA: In?

NH: God and the universe.

PA: And how do you identify?

NH: I feel like someone who has two homes, and I worked very hard for this. Israel is my home and New York is my home. In New York, I live in a big world with volume and spectrum, much more than I would have in Israel. But my heart and my soul never left Israel. I’m too sensitive to give up on that. But my life, my imagination and the world that I create from and get inspired by is universal. It’s not a specific place.

PA: And how old were you when you figured out you were an artist?

NH: I became a serious artist when I was 15 years old.

PA: You always painted though, as child?

NH: Never. The opposite. I was quite a problematic child.

PA: That doesn’t surprise me.

NH: In a nice way. But my whole life was about surfing and BMX bicycles.

PA: No way.

NH: I was a champion in Israel for BMX bikes.

PA: That’s insane.

NH: I had a beautiful, amazing childhood.

PA: That’s so nice, I feel like so many artists have such fucked-up childhoods.

NH: I had the most beautiful childhood you can ask for or dream of. And I know that because of the kind of love and protection I received, I allow myself to explore uncomfortable places because I’ve always had the confidence to know I have a place to come out of and go to.

PA: You also have this incredible confidence, which I find is quite uncommon for an artist.

NH: Art is something very complicated. But in the end, things are very simple at the same time. I never try to prove anything. This is who I am. As a person and an artist. My art has so much do with emotion and communication. Art can be attractive and have such a powerful impact on people’s minds, it has volume and impact and attitude.

PA: You have volume and impact and attitude. You have attitude. It’s a good word.

NH: I think attitude is important. For some people it’s a problem.

PA: Do you go see a lot of art?

NH: Of course. I live in New York, this is the best city to see art. There are so many great galleries and museums. I’m so grateful to be part of the art world and I get inspired by people and history and culture although a lot of the inspiration is also in your mind.

PA: When you start a new piece do you see it in your head before you create it?

NH: Until a few years ago, I did very realistic paintings for 20 years and the amount of work that took place beforehand was enormous. By the time I would start to paint, there would only be about 5 percent room for interpretation and at some point that became boring because it wasn’t about the idea anymore. I painted the “Geniuses” for five years—102 portraits—then the series Mother—13 paintings in repetition—which was very challenging as a painter. These are very technical.

PA: Do you impress yourself?

NH: You always impress yourself. For good and bad, by the way. And you always surprise yourself, sometimes in a very disappointing way. Like, you lose yourself to yourself. My conflict with myself is that sometimes I see myself as a painter and sometimes I see myself as an artist. And these are two different things. Because as an artist, you can hire painters but as a painter, you cannot do anything else. So where is the right balance between your brain, your imagination, your hand, your talent and your personality? And sometimes there is no balance. And sometimes they fight each other to be number one on the list. And that’s how you push yourself. So I reached a point where I wanted to surprise myself. And I wanted to go to a place where I could not control things.

PA: Is that where the chrome paintings come in?

NH: It took me four years to develop the chrome paintings. There is a twist on traditional painting and the history of painting, from old masters to the most contemporary paintings. I starting with oil paint as under painting and once that is done and dry, I chrome the entire canvas. After that, I destroy the chrome surface on top of the paint with a very strong air pressure gun and chemicals. You cannot control the process of what will stay on the canvas—some of it stays and some gets removed. This is exactly what happens to buildings and sculptures over time, with dirt and destruction. At the end, it all becomes one surface, the chrome and the paint. This is a new action painting. I never enjoyed working on a painting like this, it’s physically and mentally exhausting. When I finish one, I feel like a performer who just left the stage. An aesthetic event.

PA: You’re very funny. Is humor something that factors into your work?

NH: It’s rare. I keep it for life.

PA: What’s your favorite drink?

NH: Diet Coke.

PA: How do you eat your eggs?

NH: Scrambled.

PA: How do you drink your coffee?

NH: I never drink coffee. I’ve only had it about five or six times in my life. Now I drink tea, but until recently I used to drink orange juice or chocolate milk in the morning, like a child.

PA: Did you have a bar mitzvah?

NH: Yes.

PA: What did you wear?

NH: Black pants, white shirt, and a dark blue jacket. And because I was in my punk era, I had a lock necklace around my neck that was an actual lock that I couldn’t take off because I had thrown the keys away. And the rabbi didn’t want me to come like that to the synagogue, but there was no choice.

PA: That’s perfect. What shampoo do you use?

NH: Yarok.

PA: Lox or gefilte fish?

NH: What?

PA: Lox or gefilte fish?

NH: Both of them I’ve never tasted in my life. Also hummus.

PA: What?! How is that possible?!

NH: Never.

PA: How is it possible?

NH: I don’t like it. So, lox and gefilte fish—I’ve never tasted either, and I’m never going to.

PA: If you’ve never tasted it, how do you know?

NH: Trust me, I know.

PA: Okay. What’s your favorite Jewish Holiday?

NH: Hanukkah. No matter where I am, I still light the candles.

PA: Five things in your bag right now?

NH: Small book of the Zohar, a lighter, some pens and pencils, a notebook and a small digital camera.

PA: Favorite pair of shoes?

NH: Honestly, all these questions, it depends when you ask me.

PA: I’m asking you right now.

NH: I can tell you I really miss wearing sneakers without socks.

PA: OK, so which sneakers?

NH: Pumas.

Previous: The Chosen Ones: An Interview With MODI

Periel Aschenbrand, a comedian at heart, is the author of On My Kneesand The Only Bush I Trust Is My Own.