The Day Prague Spring Was Crushed

Fifty years ago tonight, the brutal crackdown on Prague Spring marked a turning point after which Western communists and fellow travelers could no longer ignore the Soviet Union’s ruthlessness.

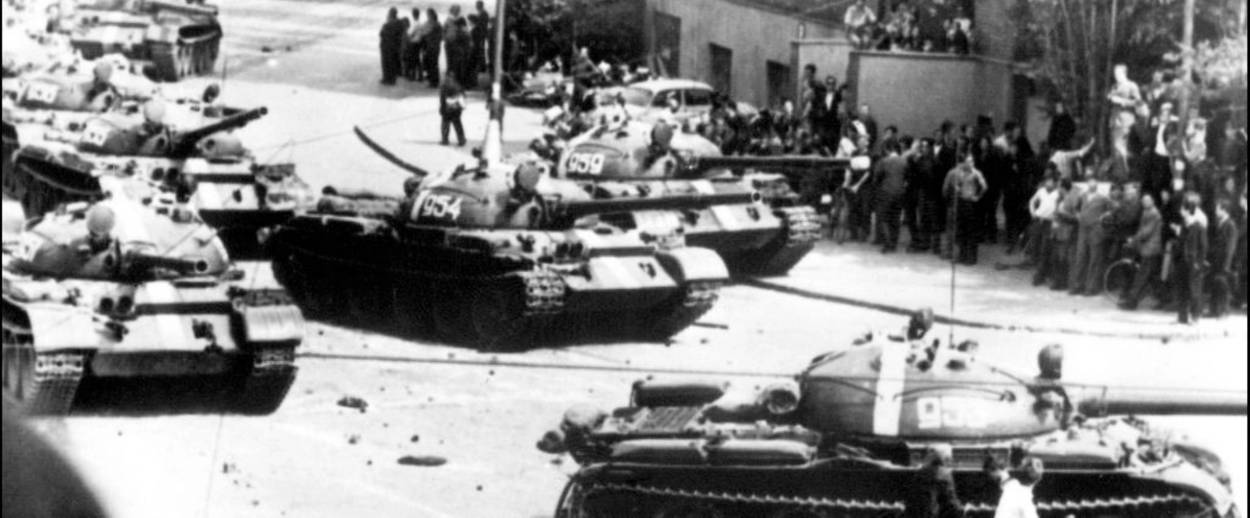

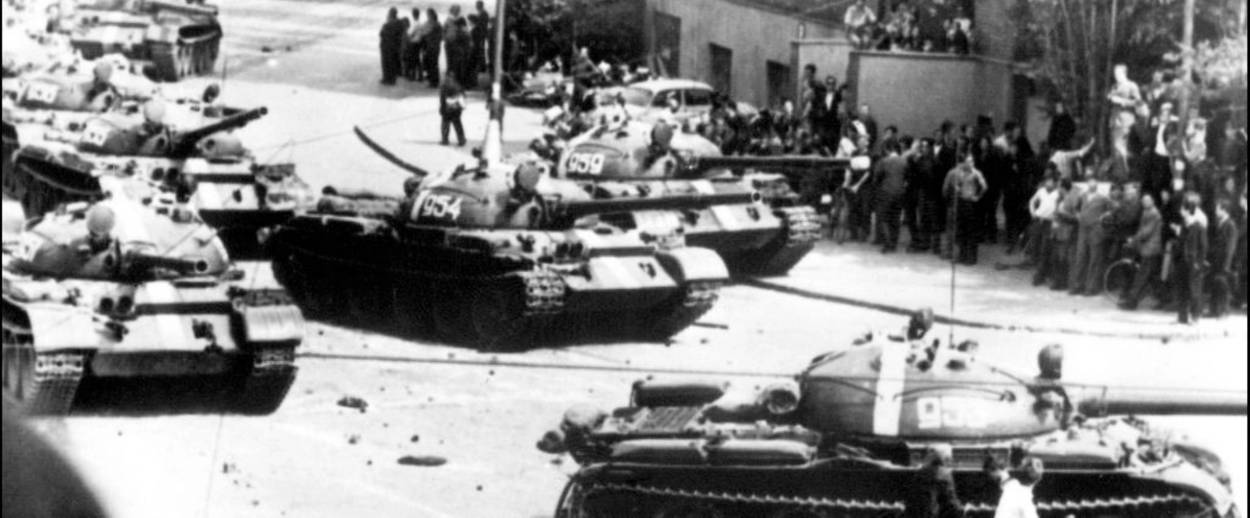

A half-century ago tonight, columns of Soviet and allied Warsaw Pact tanks filled the cobblestone streets of Prague and brutally crushed the Czechs’ attempt at liberalization. The invasion put an end to Prague Spring, the short-lived period, merely half a year, associated with that memorable and now ominous phrase, “socialism with a human face.” Springtime began whenAlexander Dubček, a reformer, was elected to the position of first secretary of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party. It ended with an invasion by a half-million strong Soviet-led army.

Dubček‘s liberalizing reforms were very popular at home but posed a threat to Soviet domination of Eastern Europe, and created fissures between different nations in the Warsaw Pact alliance. The opening up of Czech society threatened to spread to other Communist states, endangering the party’s grip on power. In response, the Soviet leadership in Moscow issued numerous threats to the Czech Communists to hold the party line. The Soviet efforts to shore up power culminated when hundreds of thousands of troops from the Warsaw Pact nations invaded under the guise of granting “fraternal assistance” to a fellow Communist nation under imminent threat of counterrevolution by reactionary forces.

This led to the crushing of the Prague Spring that we now know from the memoirs of numerous revolutionaries and leftist intellectuals. It was a turning point for many Western communists and fellow travelers; the moment when even the most obdurate believers could no longer ignore what should have already been obvious about the imperial ruthlessness of the Soviet Union. It was also the moment that the Soviet project lost its futurist trajectory with the a posteriori inauguration of the Brezhnev Doctrine as the guiding principle of foreign policy.

The invasion was carried out by about 200,000 Soviet troops as well as large detachments of Poles, Bulgarians, and Hungarians. The Albanians and Romanians refused to take part, with the Albanians going off in their own direction in the wake of the invasion.

Dubček gave the Czech army the order to stand down and avoid bloodshed, but the streets filled up with ordinary protesters. The confused young men inside the Red Army tanks were surrounded by a population who resisted heroically. Contemporary historical accounts tell us that 137 people were killed and several hundred more were wounded in the altercations with the invaders. The liberalization and hopes for a reformed popular socialism independent of the Moscow political line were crushed.

The impacts of the invasion were felt not only in the political sphere but throughout Czech society. It dealt a death blow to theCzech New Wave film movement. It also spurred a movement of underground political dissidents that would lead, many years and crackdowns later, to the so-called Velvet Revolution, history’s only revolutionary movement named after the Velvet Underground.

It comes as no surprise that today the historical memory of the anniversary has been subsumed intocontemporary European political conflicts.

As the Kremlin continues to consolidate its power by constructing an increasingly jingoistic nationalism from the fragments of Soviet nostalgia, Russia reveals itself as the successor state to the Soviet Union. Unsurprisingly, then, the anniversary of the Soviets’ invasion of their vassal state finds a muted reaction in Moscow. In fact, the history and memory of the invasion seem to have been mostly effaced from the public sphere. According to recent polling conducted by Russia’s Levada Center, around a third of the population of the Russian Federation think the Soviet military intervention was the correct course of action. As about half of the population admits to not knowing anything about the events of the time, that leaves only a very small minority of Russian citizens who now hold the view that the intervention was illegitimate.

Memory of the Prague Spring continues to bitterly divideCzech society, mostly in its fraught relationship and cognitive dissonance towards contemporary Russia. The fiercely pro-Russian President Miloš Zeman, an outspoken admirer of Russian President Vladimir Putin,scandalized large swaths of Czech society with his decision to not make any kind of speech commemorating the anniversary of the invasion. It would fall to the Slovak president to make the historic address.

Czech Communist Party leader Vojtěch Filip has gone so far as to tellThe Guardian that Soviet leader Brezhnev was actually a Ukrainian as were the core of the Soviet invading armies, thereby absolving the Russians of culpability. Ukrainian Foreign Minister Pavlo Klimkin, predictably, called these claims absurd.

Despite the efforts of politicians and ideologues, the Czechs’ history and the lessons of the 20th century cannot be reduced to mere fodder for the political interests of the moment. They remain a monument to resistance and a warning about tyranny and its allies.

Vladislav Davidzon is Tablet’s European culture correspondent and a Ukrainian-American writer, translator, and critic. He is the Chief Editor of The Odessa Review and a Non-Resident Fellow at the Atlantic Council. He was born in Tashkent, Uzbekistan, and lives in Paris.