Heinz Lichtenstern never considered himself Polish. When his hometown of Toruń, or Thorn, famous for being the birthplace of Nicolaus Copernicus, again became part of independent Poland in 1919, his family, like many other German-speaking Jews, opted to move to Cologne. Lichtenstern felt German, and there is no proof he ever spoke a single word of Polish.

Many years later, in 1944, Lichtenstern waited with hundreds of others on the ramp by the railway depot in Theresienstadt, selected for Auschwitz, while his grieving family stayed behind in the barracks. It was eight years since they escaped from the Third Reich to Amsterdam and four years since the Nazis found them in the Netherlands.

“Herr Offizier, I’m a foreign citizen,” he said. It was his last chance. “I have this.”

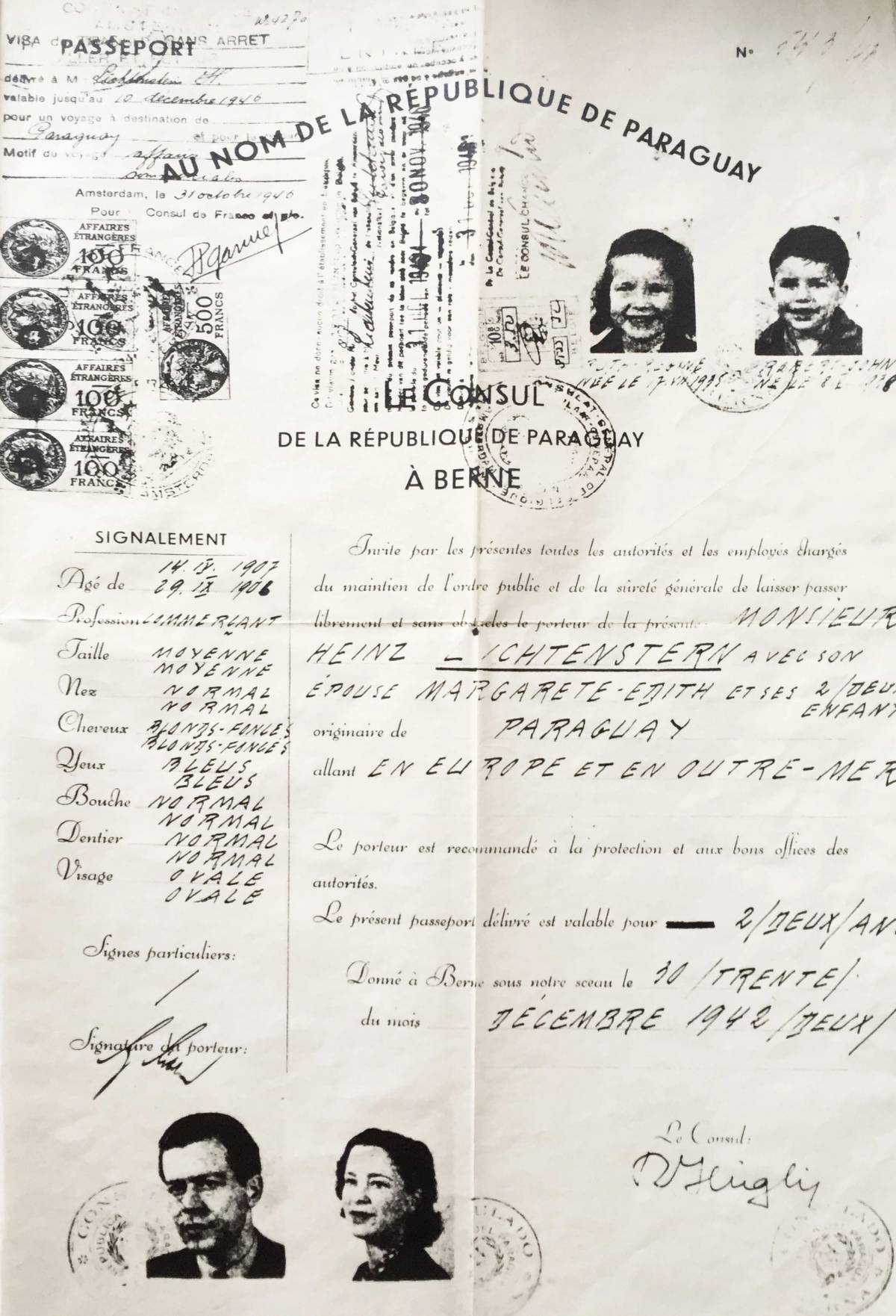

Lichtenstern, 37, produced a sheet of paper that read “Republic of Paraguay,” issued in Berne, Switzerland, by the consulate of the Latin American country. Such documents had appeared in Holland in 1943, smuggled into the country by resistance organizations from neutral Switzerland. They cost a fortune to obtain. Lichtenstern had never been to Latin America, did not speak Spanish, and probably hardly knew where Paraguay was.

Lichtenstern family passportCourtesy Heidi Fishman

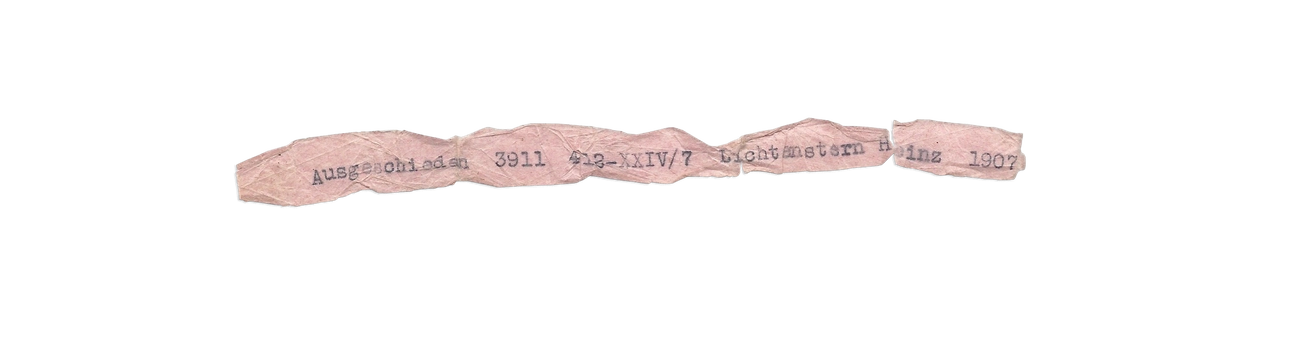

Unexpectedly, the German took the document and vanished. He appeared again: “Where is the ‘Paraguayan’?” he shouted. Soon Lichtenstern was withdrawn from the transport and reunited with his family, holding a little paper in his hand: “Ausgeschieden 3911 412-XXIV/7 Lichtenstern Heinz 1907-4-14.” The other 2,499 “passengers” boarded the train and the vast majority were gassed.

What the Nazis didn’t know was that several thousand Jews from a dozen European countries had these incredible documents, too. Some of them registered themselves as foreigners in German-occupied Poland, many only to be murdered anyway. Others showed them in the transit camps of Westerbork or Vught in Nazi-conquered Holland, and instead of being transported to be murdered in Auschwitz, they were sent to Bergen-Belsen where their chances of survival were higher. Some were miraculously exchanged for German prisoners. A few tried to use these documents to cross the Spanish border. Like Heinz, many kept them and waited until the last moment, after they had exhausted all other chances for survival. Who forged these documents remained a mystery.

Many years later, in the summer of 2017, Lichtenstern’s granddaughter K. Heidi Fishman from Vermont, a Holocaust educator and writer, read an article in a Canadian newspaper about the diplomats who fabricated Paraguayan passports during the war and recognized something unusual—a picture in the article depicted documents that looked identical to her grandfather’s. Fishman had studied it meticulously while researching her book Tutti’s Promise. “One of the reasons, perhaps the only reason I’m alive is the Paraguayan passport,” says the book’s heroine, Ruth “Tutti” Fishman, Heidi’s mother and Heinz’s daughter. “All these passports have the same handwriting,” Fishman wrote in a letter to the newspaper.

When I became Poland’s ambassador to Switzerland in late 2016, local Orthodox Jews and our Jewish honorary consul, Markus Blechner, often told me that my embassy was something special, “a holy place” as one interlocutor put it. When Heidi and I met, I already knew the so-called Paraguayan passports had not been Paraguayan: While documents had been bought for heavy prices from a Swiss honorary consul of Paraguay, the hand that filled them out was Polish. I believed they were forged to rescue our citizens under German occupation. When I researched the list of passport holders, I did not know I would find citizens of at least 15 countries—and discover the identity of the forger.

In the summer of 1945, when Heinz and his family—liberated from Theresienstadt—used their fake Paraguayan identities to attempt to reclaim their home and property, a man in his late 40s was losing his own. Switzerland had just recognized the new, Stalinist “People’s Poland,” and Konstanty Rokicki, Polish vice consul, resigned his post. A former army officer who fought the Soviets in 1920 and possessed a medal for bravery, he preferred to lose his job, home, and citizenship and live the miserable life of a political refugee than to serve the enemy. He died of lung cancer 13 years later in Lucerne, in complete poverty, living his last years in a Catholic shelter. The local services buried him in a section of a cemetery reserved for poor people, and leveled his unpaid gravestone some 20 years later.

But Rokicki’s personal notes and documents survived and left no doubt—the handwriting on thousands of forged Paraguayan documents was his. In all, he appears to have forged documents for between 4,000 and 5,000 Jews, making him one of the Holocaust’s biggest individual rescuers. We discovered his role in the forgeries only in late 2017, thanks to Fishman’s letter. At the beginning of 2018, I announced at a press conference in Paris what the Swiss police had only speculated in the 1940s: Konstanty Rokicki was the “forger from Berne.”

In fact, Rokicki was just the tip of the iceberg, a single pen serving an enormous and incredible Polish and Jewish scheme to rescue Jews from the Holocaust. Rokicki did what he could, filling out documents one by one and leveraging his consular powers, while others did what they could. And the more we searched through the archives, the more the secret, forgotten world of lifesaving Polish wartime diplomacy resurfaced.

Konstanty RokickiCourtesy of Archivum Helveto-Polonicum

Vice Consul Rokicki worked under Ambassador Aleksander Ładoś, who not only knew about everything Rokicki was doing, but sometimes tasked him, often protecting him from the Swiss police. In 1943, Ładoś went so far as to threaten the Swiss foreign minister with an international scandal if he didn’t tell the police to stop harassing his diplomats. Not only did Ładoś authorize the forgeries, he also permitted Jewish organizations in Switzerland to use Polish cables to circumvent wartime American censorship of reports about the Holocaust. Among many other operations, Ładoś sparked the intervention by the Polish Legation and other embassies: In December 1943, Paraguay temporarily recognized his fake passports.

Supported by his deputy Stefan Ryniewicz, who handed bribes to the Paraguayan consul and forged several passports himself, Ładoś created a secret team of rescuers within the embassy who worked together with Jewish groups in Switzerland to try desperately to save their kinsmen. “Without these gentlemen we would not have been able to rescue anybody,” Recha Sternbuch, known as the “heroine of rescue” and one of the leaders of Vaad Hatzalah, wrote after the war. The tribute Ładoś paid to Sternbuch was equally unequivocal: “Together we saved Jews from the concentration camps.”

Another key member of the Polish team was Julius Kuhl, a Polish Jewish diplomat at the Legation. Kuhl was 29 years old, extremely clever, and known for having widespread contacts with the entire Jewish community of Switzerland—from A to Z, “Agudath to Zionists,” as some local Jews joked. Given the complexity of prewar Polish-Jewish relations, Kuhl probably played a crucial role in convincing Jewish organizations that the Polish diplomats were indeed eager to help, thereby creating one of the biggest common efforts between Poles and Jews to rescue victims of the Holocaust. It is widely believed that Kuhl directly introduced Recha and her husband, Isaac Sternbuch, to Ambassador Ładoś, thereby securing the protection of a recognized Allied government for a large number of Jewish rescue operations in Switzerland.

The first identified passport was issued to a Jewish couple from Kraków in May 1940, the last documents probably in summer 1944. But when in 1942 the influential and respected Zurich-based merchant Chaim Eiss, leader of Agudath Yisrael Schweiz, joined the scheme, the whole operation grew rapidly. A frequent guest at the Legation, Eiss was focused on providing documents to rabbis and yeshiva students—initially to rescue his own daughter and son-in-law from Antwerp. Until his sudden death in November 1943, Eiss did not rest, providing help to thousands more and depleting his own finances and health. It is widely believed that Recha and Isaac Sternbuch stood behind Eiss, and that Isaac filled his role after his death.

In 1943, the passport forging operation grew even larger when Ryniewicz and Rokicki tasked Abraham Silberschein, a member of Poland’s prewar parliament and respected lawyer now representing the World Jewish Congress, to prepare lists and addresses and to provide sustainable financing. Silberschein and his agents helped build the network in Poland, the Netherlands, and even in the German Reich. And they enlisted other consuls, representing Honduras, Haiti, and Peru, to provide blank papers.

I believed passports were forged to rescue Polish citizens under German occupation. When I researched the list of passport holders, I did not know I would find citizens of at least 15 countries—and discover the identity of the forger.

While a lot has been written about Polish-Jewish relations during the Holocaust, the current debate mostly focuses on the attitudes of individuals or groups of individuals among the Polish population who were then on occupied Polish soil. It very rarely concerns the state of Poland as represented by its exiled government. Unlike other European countries such as France, there was never a collaborationist Polish government. The Nazis ruled occupied Poland directly, with no cooperation from the state bureaucracy or other organs of the Polish state.

The Polish government-in-exile unquestionably continued the battle against Germany and, as Menachem Rosensaft put it, “was one of European Jewry’s few allies during the Holocaust years.” Moreover, its diplomats, quite often veterans of Poland’s struggle for independence before 1918, had previous experience with illegal operations, and accepted forgery as a legitimate method of rescue.

Heinz Lichtenstern and the three members of his family are just a tiny fraction of the 8,000 to 10,000 Jews who were in possession of what became known as “Ładoś passports,” and just four names among the 3,253 we have identified so far. Of course, not all the holders of such passports survived, and not all those whose names appeared on such documents knew they had been issued. Nor did the passports always play a role in their rescue. Overall, we estimate that some 2,000-3,000 bearers of Ładoś passports survived the war, under various circumstances.

In their massive effort, Ładoś, Eiss, Rokicki, Silberschein and others often rescued or tried to save people they did not even know, like Yehiel Feiner, the writer better known as Yehiel De-Nur or Ka-Tsetnik 135633; Itzhak Katzenelson, the Polish Jewish poet; Hanna “Hanneli” Goslar, the best friend of Anne Frank; and the latter’s Polish counterpart, teenage diarist Rutka Laskier. Among those who survived, one may find the future chief rabbi of Amsterdam, Aron Schuster, and the Bluzhover Rebbe, Yisroel Spira. At least one survivor died in the Israeli War of Independence, and at least two in the Polish guerrilla war against the Communist regime.

Aleksander Ładoś with General Prugar-Ketling, the commander of the Polish Second Rifle Division interned in Switzerland in 1940 after the defeat of FranceCourtesy of Archivum Helveto-Polonicum

Passports were also forged for Lelio Valobra and Enrico Luzzato, Jewish Holocaust rescuers from Italy, as well as for Fanny Schwab and other leaders of the French Œuvre de secours aux enfants. Frumka Płotnicka and the brothers Kożuch decided not to rescue themselves with their papers, but died in the short-lived uprising in the Będzin Ghetto. Yitzchak Zuckermann, Cywia Lubetkin, and Tosia Altmann, fighters in the Jewish Combat Organization in Poland, probably never learned about the existence of their documents.

Initially the Polish diplomats involved in the scheme believed Jews bearing foreign passports would be spared and interned instead of murdered. But when, by 1944, it was clear that the Nazis did not always honor the documents, Ładoś then supported Vaad Hatzalah in its attempts to bribe Heinrich Himmler and obtain the liberation of the 300,000 Jews still alive in the Reich. We have found several cables documenting the details of the subsequent attempt to bribe the Nazis, as Ładoś permitted the Sternbuchs to freely use the Polish diplomatic pouch.

Ładoś rarely spoke about his lifesaving operation. He promised to tell the whole story in his memoirs, but passed away in December 1963 without finishing them. His subordinates were equally silent. During the war, Agudath wrote a letter to the Polish government in London thanking its Bernese diplomats for having saved many hundreds of people. For the Polish government-in-exile, the existence of the scheme was not a big secret, as two consecutive foreign ministers and at least one prime minister demanded that Ładoś “organize” passports for individual Jewish figures, and the entire network of Polish embassies and consulates intervened both in many Latin American capitals and in Washington to obtain recognition of the Ładoś forgeries.

Yet the Agudath letter was immediately classified—it was January 1945, the operation was still ongoing, and the lives of passport holders were still in danger. We found this paper, attesting to the partnership between the Polish Legation and Jewish organizations, only after 72 years.

In 2019, Rokicki was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem; recognition for Ładoś and Ryniewicz remains undecided. All six members of the Ładoś group were posthumously decorated by the president of Poland two years ago. The gravestone of Konstanty Rokicki was restored in 2018.

Heinz Lichtenstern passed away in 1992 in Switzerland after having lived in Brazil, the United States, and the Netherlands. He never knew that he had been saved by the Polish government, which nurtured a secretive and lifesaving collaboration between Jews and Poles.